The Harvard course Humanities 10: “Humanities Colloquia: From Homer to García Márquez and From Joyce to Homer” has some singular features. Limited to 90 students, all freshmen, it covers a different major work each week and so moves through 2,500 years of art and literature at a brisk clip. The course includes intensive writing instruction and is the only Harvard College course that satisfies Harvard’s expository writing requirement other than the dedicated “expos” offerings. Remarkably, tenured faculty members, not graduate students, teach the six sections of 15 students each. These include the course’s founders—Louis Menand, Bass Professor of English, and Stephen Greenblatt, Cogan University Professor—alongside other luminaries like anthropologist David Carrasco and historian Jill Lepore.

For senior faculty at a large research university to lead these weekly small-group discussions in a lecture course is almost as rare as one of them serving as a staff writer at the New Yorker, though, as it happens, this course boasts not one but two (Menand and Lepore).

“We love it,” Menand says. “The texts are fun to teach, and the freshmen are excited by them. It started as a conversation between friends. Steve and I took inspiration from a course on what they called ‘important books’ that Lionel Trilling and Jacques Barzun offered at Columbia in the 1930s. We made a list of 12 books we felt every educated person should know.”

In part, Hum 10 was also a creative response to the general flight from the humanities triggered by the economic collapse of 2008. “Student enrollments started to drop,” Menand explains, “and not just for concentrators, but in taking humanities courses, period.” Hum 10 has been pulling them back with the magnetism of its teachers’ profound belief in the value of literature, philosophy, history, and the arts. “The humanities are the record of human experience,” says Menand. “It’s the history of our species trying to figure out what it means to be human. For thousands of years, human beings have created these works of art, literature, and philosophy—wouldn’t you want to know what they’ve come up with?”

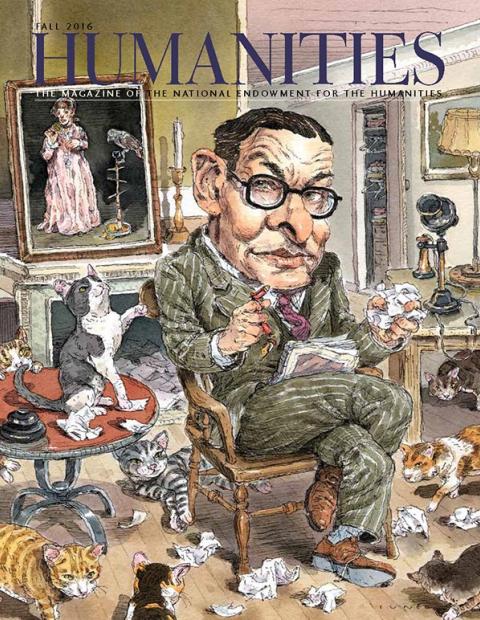

Menand (generally called Luke, a nickname since childhood) is perhaps best known for his essays in the New Yorker, where he has published since 1991; he has been a staff writer since 2001. In recent years he has focused on book reviews, and his pieces explore a spectacular range of subjects. In a lucid, engaging prose style, Menand has probed the likes of Barry Goldwater, self-help books, John Maynard Keynes, Dr. Seuss, the paperback revolution, Maya Lin, Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, creative-writing programs, the Bobby Fischer-Boris Spassky chess match, Timothy Leary, the price tag of sports, Norman Mailer, Mark Rothko, Elvis Presley, and Henry James.

“He’s an absolutely brilliant intellectual storyteller,” says Greenblatt, author of The Swerve. “That’s what makes his writing in the New Yorker and his books so outstanding. Luke can take very complex material and craft a compelling, vivid narrative. Some writers try to do this, but thin out the material and betray it. With Luke, it’s the opposite: You’re getting closer to the rich complexity, but also following a powerful story.”

In Menand’s NEH-supported book The Metaphysical Club: A Story of Ideas in America (2001), he deftly blends biographical material and historical events, setting both in a social and cultural context. What emerges is an enthralling story that illuminates the history of ideas. The narrative centers on a conversational club that Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., William James, and Charles Sanders Peirce formed in 1872 in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

The club met for only one year, but it was an intellectual crucible that pushed back against European metaphysics and gave birth to the philosophy of pragmatism. The Civil War, along with emergent disciplines like statistics and evolutionary biology, powerfully shaped this philosophical movement. The Metaphysical Club, which took a decade to research and write, received both the Pulitzer Prize in History and the Francis Parkman Prize from the Society of American Historians in 2002.

Though a professor of English, Menand is more a cultural historian than a literary critic. He took a degree in creative writing from Pomona College in 1973, where “I was writing pretty bad poetry,” he says. After one year at Harvard Law School, he earned a doctorate in English and comparative literature from Columbia in 1980.

Now, he has again devoted a decade of work to the cultural history of a seminal period—this time, the Cold War era of 1945 to 1968. His next book deals with developments like Abstract Expressionism, the Beats, and the spread of American popular culture after 1950. Although some feel that today’s global, digital culture has left the Cold War era behind, Menand is having none of it: “They created the world we live in.”