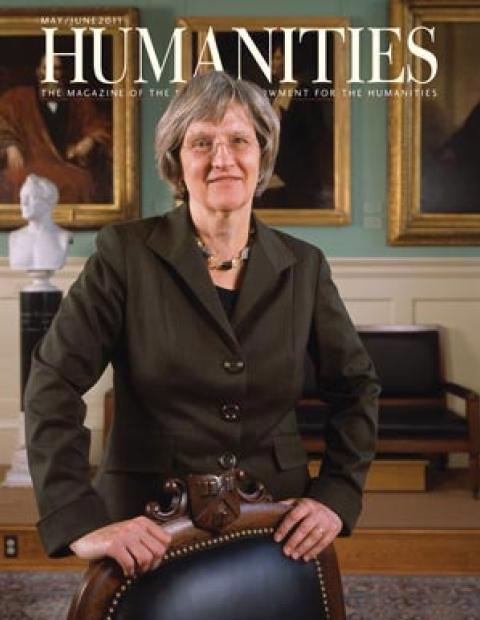

President Drew Faust of Harvard University is this year’s Jefferson Lecturer, the fortieth recipient of this honor, the highest award in the humanities bestowed by the United States government. An important leader in American higher education and a well-known scholar, Faust is the Lincoln Professor of History in Harvard’s Faculty of Arts and Sciences. Before serving as president, she was the founding dean of the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, and for many years was a professor of history at the University of Pennsylvania. Her studies have resulted in several books notable for their original thought and thoroughgoing research. Her most recent is This Republic of Suffering, which takes its title from the words of Frederick Law Olmsted and its subject from the vast death toll of the Civil War. She has also written books about the effects of the war on Southern womanhood and about the lives and culture of slavery’s apologists in the antebellum South.

JIM LEACH: You were brought up in the Shenandoah Valley. As a child you must have been aware of the Civil War legacy and probably had a sense for the nineteenth-century past.

DREW GILPIN FAUST: Very much so.

LEACH: How did it influence you as you grew up?

FAUST: I felt very much that I lived in history—in a couple of different ways. One was the presence of the Civil War and living on a highway called the Lee-Jackson Highway. And living surrounded by those gray, black-bordered road signs that the state of Virginia put up to mark historic sites. We had many of those: the old mill in Millwood from the eighteenth century; Carter Hall, up on the hill that we had known had been an important outpost of the Carter family from the Tidewater. And Civil War monuments everywhere: Cedar Creek, the many battles of Winchester.

And then in the cemetery where now my parents are buried, but at that time it was my grandfather and others, next to the marked gravestones and my family plot at this beautiful little setting called the Old Chapel, there were many moss-covered stone grave-markers that said, “Unidentified Confederate.” They were the dead of skirmishes that had taken place in that much fought-over area.

My older brother became a Civil War aficionado and collected stuff. Which included, ultimately, a John Brown pike and a bunch of rifles and all kinds of things. But from the time he was much smaller he had us playing Civil War.

And he was always Lee, so I had to be Grant. But somehow I always lost. And it took a while before I figured out that history had turned out otherwise. So, I had a very special version of the Civil War story told to me when I was little.

LEACH: But the Civil War wasn’t quite over for you. When you were nine, you wrote a letter to the president of the United States, Dwight David Eisenhower.

FAUST: That was the other part of history that I lived in: The stirrings of the Civil Rights Movement were emerging all around me when I was a young child.

And there was Harry Byrd, who was not just our senator, but really our neighbor. He lived in Clarke County, as we did, and he was very much a presence. Byrd was the person who championed the notion of “massive resistance.” Rather than integrate in response to Brown v. Board of Ed., he proclaimed that Virginia should close its public schools. The discussion and debate that surrounded that were very much in the air of my childhood.

But these were not issues that anybody spoke about out loud when I was growing up. There were just ways of doing things that separated black and white. There wasn’t a vivid discourse of race. It was just taken for granted.

And so with the articulation of these principles of separation and inequality as a defensive response to the emerging civil rights revolution, I was struck, even as a young child, by their inconsistency with the values I had learned at church, as I made reference to in my piece about my letter to Eisenhower, and in school as we learned about democracy and America, those political values that had been transmitted to me by the time I was nine years old.

LEACH: In your article you also noted the word “nullification” was in use then. And, interestingly, in the last year it’s crept back into the American political vocabulary. Do you draw a connection to the Civil War, or are we talking about a different conception of states’ rights today?

FAUST: Well, the notion of nullification emerged in South Carolina in the 1820s and thirties and became a kind of emblem of opposition to federal power. In South Carolina, this was tied up with the defense of slavery.

It was officially about the federal government’s power to impose tariffs. But, as much historical research has shown, the specter behind that argument was really that of slavery and of the South Carolinian demographic reality of a black majority. The white minority felt the need to exert control over the enslaved population. The federal government’s intervention was seen as very threatening to that sense of local control.

So, nullification emerged in that context and was really a precursor of the language of states’ rights and secession that followed it a few decades later. Picking up that language from the past is done self-consciously as an invocation of resistance to centralized federal power, but it has other histories as well.

LEACH: You went to prep school in Massachusetts, college at Bryn Mawr, and then graduate school at the University of Pennsylvania. But one has the sense you continued thinking about your Southern heritage through your chosen field of study.

FAUST: When I began studying history at Bryn Mawr, it was a very traditional history curriculum in which wide preparation in European history was required. So, as an undergraduate, I studied European history and did essentially no work in Southern history.

I wrote a senior thesis on American foreign policy, which I was very interested in, it being the Vietnam era. And then, after college, I was uncertain what I wanted to do and worked for a couple of years for the Department of Housing and Urban Development.

I decided to go back to graduate school. At Penn there wasn’t the same strong tradition of Southern history that had come into being at, for example, Yale and Johns Hopkins. C. Vann Woodward was at Hopkins before he ended up at Yale. And David Donald taught at Hopkins before he came to Harvard. There were a lot of very powerful, influential historians who were studying the South, and that was intriguing. But what began to become even more interesting as I moved into my graduate historical studies was one aspect of Southern history, which was the revolution in the study of slavery.

That was part of a whole overturning of traditional historical practice as well as of the substance of historical conclusions. The study of slavery required a different approach to sources and a different approach to the work of doing history than what had preceded it.

This work was often characterized in the 1960s and seventies as the history of “the inarticulate”: the notion being that history had heretofore focused on the elites who were educated to record their experiences. The public record similarly documented that history in politics, business, the military, and other influential spheres built around record-keeping institutions.

During the historiographical moment of the late sixties and early seventies scholars began to inquire about the rest of the population that hadn’t perhaps been so literate and hadn’t had the opportunity to have their almost every word preserved in an archive. After all, such people were individuals with lives and with agency and with influence on the outcome of historical events.

In my generation of historians, there was tremendous energy invested in studying workers and then women and also slaves and others who were part of the so-called “inarticulate.” To study those who don’t leave traditional written records you have to look much more broadly at sources of information. And those might, for example, be demographic.

In my book about James Henry Hammond, I used his records of slaves and their births and deaths, records that he kept essentially for economic reasons, to map out family ties and to see how long-lived families were and how children’s names were chosen. And I could see things that Hammond himself probably never saw. For example, I was able to trace a child’s name back two or three generations to someone in that slave line of descent who had that same name. I could see that slaves were naming their children after their grandparents.

At this time there was a belief that slaves had no sense of family because it had been destroyed by the oppressions of slavery. But here were slaves clearly affirming long and deeply held family ties. So, that’s one way demography can lead to insights.

Material culture, objects, archaeology, what can they tell us about the slave experience? What are the variety of other materials that we, as historians, hadn’t bothered with before that give us insights into a population that didn’t necessarily keep diaries, whose history wasn’t preserved in a formal process of record-keeping?

This was fascinating to me as a way of expanding how one does history. The arguments over the interpretations of this history were captivating as well.

LEACH: And yet records, especially those people create for themselves, are especially important to your work,even though, as you have noted, a historian must keep in mind that when people write of their times and themselves they can be misled or misleading.

How do you put all of this together? Is your emphasis on the original word, or is the emphasis on the context in which the word is made?

FAUST: What has always interested me most about history is trying to understand how people see their own world. And how they create the structures of meaning and understanding that serve as the lens through which they view what is around them and the events that confront them.

And that led me, after I finished my PhD, with a yearlong grant from the Social Science Research Council, to study anthropology and to explore what anthropologists call “worldview.”

That reinforced my interest in the notion that if you can understand how someone sees the world differently from you, then you learn something about your own world too. In doing so, you see that you have created a set of lenses for yourself or you have appropriated a set of lenses for yourself.

There is always a sense, which comes from this kind of inquiry, of the contingency of things and how they could be otherwise.

LEACH: With our involvement in Iraq and Afghanistan today, we seem to be learning again that sometimes it’s harder to end a war than to start one. The reason I mention this is that in 1989 you made quite a mark with the argument you presented to historians that an underestimated explanation of why the Civil War ended in the manner it did may have related to the role women played in convincing the menfolk to cease and desist.

How did you make this argument and how do you go about pointing out the historical data to justify it?

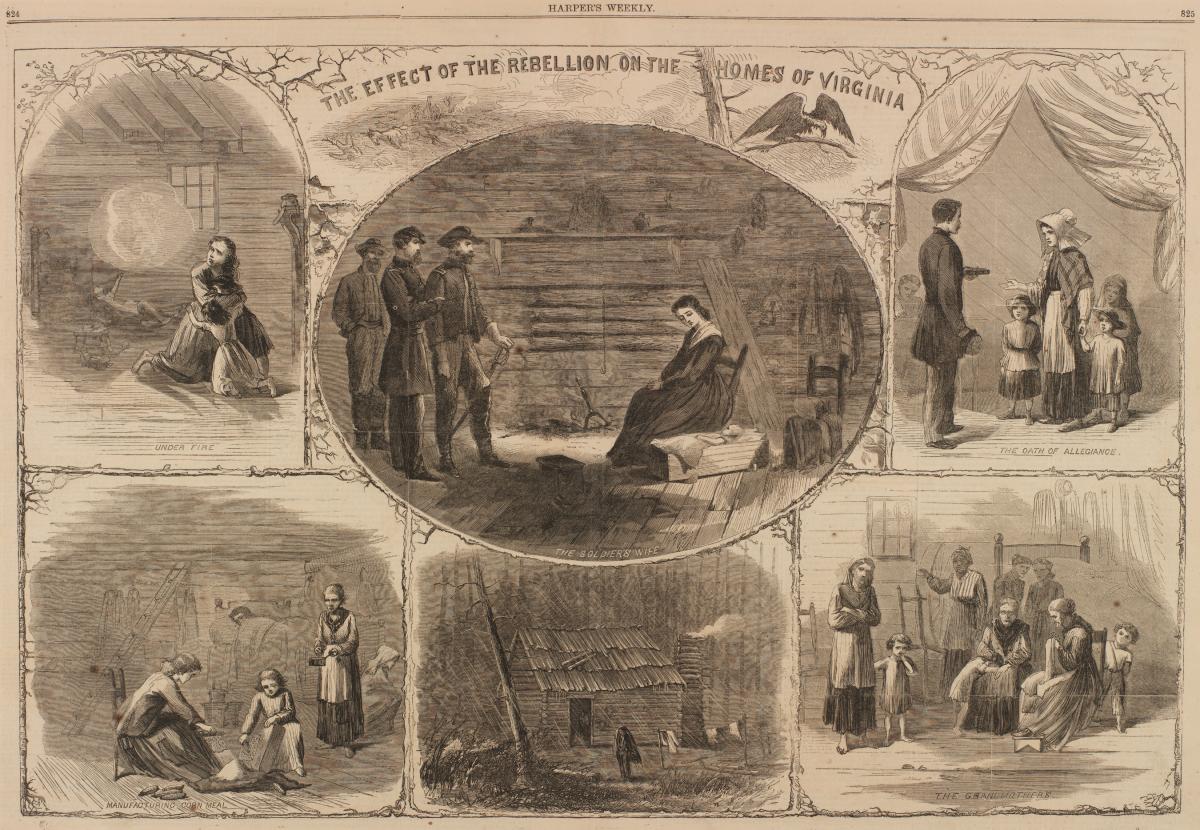

FAUST: I made an argument that women’s exasperation and exhaustion in the Confederate South led them to focus increasingly on their own interests in preserving what remained of their property and their loved ones. They began to question the sacrifices they had made. And I used that perception of women’s changing views of the war to suggest that this may have been a real factor in the erosion of the Confederate army.

That army was not simply destroyed through death and disease, but also through all those men who seemed to disappear back into the hillsides. Cold Mountain is a recent literary rendering of such a story.

It seemed to me important to put into the conversation about Civil War history some dimensions of explanation and understanding that hadn’t been there. And, as we looked increasingly at the home front and its role in the war, I thought we had a lot to learn from thinking about it as a factor in one of the perennial questions of Civil War historiography: Why did the South lose the Civil War? People have been trying to answer that for over a hundred years.

And it seemed to me that one way of responding, a way that added a perspective from the new kind of history that was being done of actors who hadn’t been included before, was to suggest that indeed their agency included having an impact on this most fundamental of Civil War questions.

LEACH: Let me ask you about James Henry Hammond, about whom your wrote a biography. Who was Hammond and what was his role in the South in the years leading up to and during the Civil War?

FAUST: I loved writing that biography of Hammond because he wrote down everything he did. He was a biographer’s dream. And he was always such an excessive character. He embodied principles—not principles in terms of positive values, but characteristics—that so reflected what he saw as the route to success in the Old South. He became almost a barometer for his culture as he tried to take on each of its requirements for advancement.

The biography grew out of my first book, which was a study of a group of intellectuals who wrote defenses of slavery. I was fascinated by how anybody could do such a thing and the bases on which they justified this to themselves and how they came to see the world in this way.

And as I wrote that first book, James Henry Hammond being one of the individuals I studied, he rose to the fore in my mind as an individual who, as a plantation owner, as a senator, as a governor, as a writer and intellectual, offered windows into so many aspects of the South in the pre-Civil War and the Civil War era.

I felt the biography would offer important insights into some of the most important dimensions of that antebellum Southern culture.

LEACH: Your most recent book is This Republic of Suffering, which could perhaps be described as a compendium of how families of the nation deal with loss. How did you become interested in writing a whole book on the war’s death toll and its social consequences?

FAUST: It began with my book on women of the Confederate South and with my engagement with their diaries and letters. And as I read the seemingly endless numbers of them I was increasingly struck by how often women spoke about death and how central was their perception of death and the fear of death and the need to manage death.

And, I thought to myself, of course it was. If 620,000 Americans died—and that was the equivalent of 2 percent of the population or six million Americans today—no wonder they were so preoccupied with death. But why haven’t we Civil War historians been equally preoccupied with death?

As I thought about the six million analogous number, I couldn’t imagine how our society today could deal with that. And that gave me a new perspective on what it must have meant in American society in the 1860s. How did they deal with the bodies? What does mourning mean when it is so all-pervasive? How did they explain this loss, in both religious and political terms? “How,” to quote a prominent Confederate, “does God have the heart to allow it?” And what does it mean for the nation-state that has required so much sacrifice? And that’s what sent me off into this set of inquiries.

LEACH: One final Civil War question. We all share a common history in America, but we don’t necessarily share a common perspective. If you were to pick out one or two thematic perspectives that we should all come together as a people to think about the Civil War, what would you suggest?

FAUST: One would be about citizenship. And the opening of citizenship to individuals who had been excluded from it. That would be an extremely important theme.

Another would be the importance of the United States and Lincoln’s arguments for the United States. One of the most striking aspects of the Civil War in my mind is why the North fought. Why they didn’t just let the South go. Lincoln rendered the United States as the “last best hope of earth” at a time when democracies around the world were struggling and it looked like that form of government might not survive.

And when Lincoln articulated that, he was able to mobilize the North to fight an expensive and devastating war. Those values seem to me ones that are important to underscore as well.

LEACH: Well, you have commented elsewhere on the importance of education in the American dream. And there’s an oft-cited assumption that education may be the civil rights issue of this century. Does this observation strike you as valid?

FAUST: It does, and it’s one that I’ve quoted or repeated often, because education is the avenue into full participation in the society in which we live. We’re in a time in which knowledge has paramount importance in how our world will move forward and how people will claim their place as contributors to that world. Education is an essential prerequisite for full membership in that community.

LEACH: At Harvard, under your leadership, ROTC has been welcomed back to campus after a forty-year hiatus. How did this come about and what was the thinking that went into this policy change?

FAUST: When I became president, the issue of ROTC’s absence from Harvard campus was already one that was very much in the air and much debated. And it was an issue I was confronted with even before I became president.

I feel very strongly about the importance of inclusiveness in the military. I think back to the Emancipation Proclamation and how it welcomed black soldiers into the military.

Citizenship and military service have been very closely tied in our history. In the seventies, the women’s movement made military service a big focus of the struggle for women’s equality. So, I cared a lot about the overturn of “Don’t ask, don’t tell,” as another step in the nation’s progression towards inclusiveness.

I also believe that it is important for the military to be a part of American life and not isolated from the mainstream. Just today, I was talking to a couple of people in my office who had helped work on the return of ROTC. And we realized that all of us had parents who served in World War II. This was the norm when we were growing up. The army and the military services were integrated into American life in a way they no longer are. Only 1 percent of Americans now serve in the military.

I felt that Harvard and Harvard students should have connections that would promote this kind of integration of the military with civilian forces and civilian realities. I felt our students would learn a lot, and I felt that it was important for the military as well.

I also am very conscious of what General David Petraeus articulated here in a commissioning ceremony for the ROTC cadets a couple of years ago, which is that a soldier’s most important weapon is ideas. And it seems to me very important that the education that Harvard has to offer be something that individuals in the military are able to experience and are encouraged to experience. That was a significant driver in this decision as well.

LEACH: There is in Lincoln’s background that dimension, and also the obverse dimension. In July of 1862 he signed the Morrill Act, which established land-grant colleges, with the implication that even in wartime we needed to expand educational opportunity for American citizens. Do you find it remarkable that is, in the middle of our most horrific war he made a stand for expanding access higher education?

FAUST: Well, he was a person for whom education was so important. And he had to struggle so hard to get access to it and to teach himself in large measure. So, he was an individual who had great respect for learning. And that, I believe, was part of his motivation. Also, if you look at the Civil War, it was a time when the American government was able to establish a number of forward-looking policies that strengthened the nation. The Transcontinental Railroad is another example. The Morrill Act seems to me consistent with those.

LEACH: The two acts—one related to the infrastructure of ideas, the other to the infrastructure for transportation—were signed a day apart. Bringing the subject back to the here and now, I can attest, having taught briefly under your leadership at Harvard, that the student body and faculty have found you to be an extraordinary president, able, like Lincoln, to manage deftly an institution of many parts and diverse egos. I wonder, Do you have any advice on what the attributes of a university president should be in today’s world?

FAUST: Stamina, curiosity about a wide range of intellectual fields and about a wide range of people. It is important to take joy in the variety of things that go on at a university. Having a completely different subject occupy each consecutive hour of my day on many occasions is a wonder and a thrill. So, that’s one set of attributes.

I would say also that what I just described as enormous variety and range also means that you have many, many constituencies. Each of which has important messages to deliver to you and important things they want from you. And so you have to be able to listen to them and, in a sense, going back to what I said about studying history, see the world through their eyes.

Understand what it is that is so significant to them and then try to use that understanding to bring them to you and to what you see as the most important agenda for the university. And so to incorporate their perceptions but also to unite those individuals with others who may not necessarily agree with them.

LEACH: The American university is the hallmark of our land, Harvard being our emblematic institution. And we’re proud of the role it and you have played in helping insure that America leads the world in almost every academic discipline.

FAUST: You’re very kind and very generous.