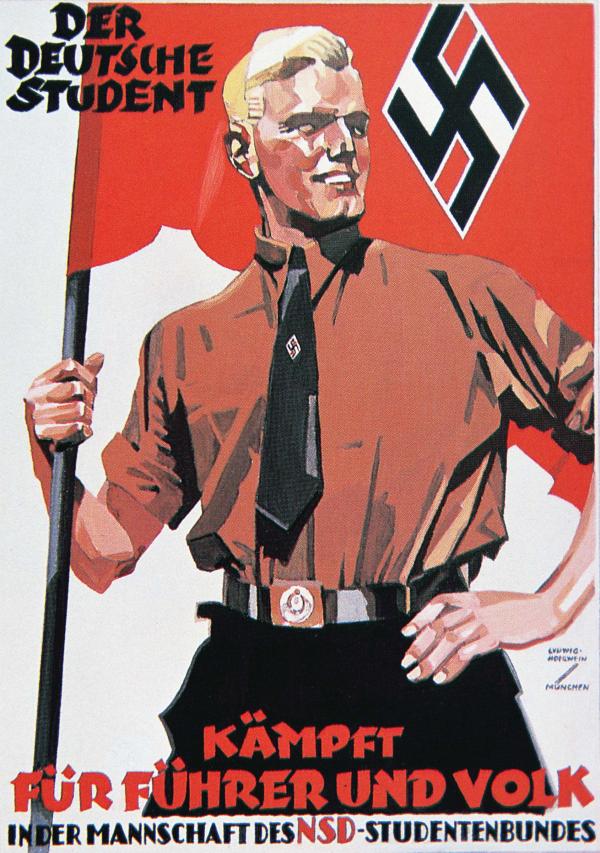

High culture played an important political role in Hitler’s Germany. References to music, history, philosophy, and art formed a key part of the Nazi strategy to reverse the symptoms of decline perceived after World War I. Allusions to great creators and their works were used as propaganda to remind the Volk to love and worship their nation. In the words of the French scholar Eric Michaud, author of The Cult of Art in Nazi Germany, the Nazis used culture “to make the genius of the race visible to that race.” And to cap off these images of a great national culture, the Nazis heralded Adolf Hitler, the Führer, as an artistic leader.

As Michaud put it: “Hitler presented himself not only as a ‘man of the people’ and a soldier with frontline experience (Fronterlebnis), but also and above all as a man whose artistic experience constituted the best guarantee of his ability to mediate the Volksgeistand turn it into the ‘perfect Third Reich.’”

The revival of a culturally rich Germany as the so-called Third Reich, however, would be achieved only once those whom the Nazis considered its enemies were all destroyed. So war and culture went together in the National Socialist agenda. Art, said Hitler’s propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels, “is no mere peacetime amusement, but a sharp spiritual weapon for war.”

To understand how Nazis employed culture to define and promote their broadest ambitions, I looked to German mass media, in particular the main Nazi newspaper, the Völkischer Beobachter, whose cultural pages I examined for the years 1920 to 1945. While the Nazi co-optation of many great figures in the Western intellectual tradition during these eventful years proves revealing, one need look no further than the party’s claim on Friedrich Nietzsche to see how culture became entwined in the discourse of politics and war in the pages of Hitler’s foremost propaganda outlet.

Fitting Nietzsche’s ideas into a single worldview was no simple matter, but this was precisely the mission of the Völkischer Beobachter’s editors and writers: to make even complex ideas such as Nietzsche’s appear to coordinate with the main tenets of Nazism. Looking into the shifting terms with which the daily newspaper presented Nietzsche helps us toward understanding how the Nazi party attempted to place his biography and writings—along with the tradition of Kultur as a whole—at the service of the Nazi outlook.

In addressing the “Germanness” of Nietzsche, however, the cultural politicians of the party faced some difficulties. The newspaper did not try to verify Nietzsche’s racial origins—as it did for many other Western creators, including and especially Wagner and Beethoven—despite the fact that he occasionally claimed to be of Polish heritage. But it did have to confront indications that the philosopher rejected nineteenth-century trends of nationalistic identification.

As one contributor to the Völkischer Beobachter wrote, there is “one important point in Nietzsche’s mental attitude on which even his friends have remained silent, from which they tried to distance themselves as much as possible: this is the matter of Nietzsche’s attitude toward Germanness and the state.” The philosopher, according to the paper, had seen with “sharp eyes” that while the Second Reich had been formed, it still “remained a shell without content” under Otto von Bismarck’s Realpolitik. To him, nationalism was the “illness of the century” because it “attempted to hide its emptiness.” In his words, “Nationalism as it is understood today is a dogma that requires limitation.”

But the point to keep in mind, according to the Völkischer Beobachter, was the qualifying phrase: “as it is understood today.” Nietzsche’s opinions about the German state could be understood only with reference to this phrase—that is, as critiques of his own specific time, not as categorical rejections of German nationalism.

This opened the way for the newspaper to present Nietzsche as a fervent patriot and strong representative of “Germanness.” In fact, the paper reminded, Nietzsche actually said of himself that “I am perhaps more German than the Germans of today.” And he valued the “earnest, manly, stern, and daring German spirit.” He knew that “there was still bravery, particularly German bravery,” that is, “inwardly something different than the élanof our deplorable neighbors.” Compared with the French essence, in particular, he was “consistently, strongly, and happily conscious of the virtues” of the German character. Above all, Nietzsche held that “it is German unity in the highest sense which we are striving for more passionately than for political reunification—the unity of the German spirit and life.”

Very few others “saw things so clearly” in those days, said the Völkischer Beobachter. As if on a mission to confirm the philosopher’s Germanness, another contributor traveled to Sils-Maria, wandered the region, and ruminated on passages Nietzsche had written there. The landscape, Ernst Nickell reflected, is “consecrated by German fate and German tragedy.” Nietzsche “needed this landscape; he had to stand near the highest things and the firmament”—because he was “German despite everything.”

Nietzsche was, however, rather ambivalent about politics, having called himself the “last anti-political German of them all.” But Nazi propaganda rigorously promoted the view that the primary creative impulse was as much political as it was artistic. The picture of Nietzsche thus had to be corrected to bring out his political side.

The Völkischer Beobachter admitted that “we find here at first view a sharp contrast with today’s [National Socialist] thinking”—but only at first glance. According to the paper, what Nietzsche understood by the term “state” was completely different from “our idea of the state today.” For him, politicization meant democratization, i.e., the greatest good for the greatest number. This Nietzsche hated, the paper said, because “general prosperity would make mankind too lazy to invest powerful energy in a great individual— in a genius.” That is why Nietzsche wanted “as little state as possible.” A volkish state, directed according to Nazi ideology, however, would revive the genius of the nation, and therefore earn Nietzsche’s support.

The paper acknowledged that Nietzsche had other views that seemed “the complete opposite of our views today.” For instance, he viewed culture and the state as antagonists. This, perhaps, should have made him the oddest of conscripts to the Nazi campaign to subordinate culture to politics and war, but that was not the party line. Such ideas of Nietzsche’s, the Völkischer Beobachter insisted, were likewise conditioned by his own times:

The German Reich had had the misfortune to achieve its external form when there was no longer any inner content. The classical heights of German education had sunk, the song of German Romanticism sounded only from afar. On the other hand, Realism was on the rise, leading more and more toward materialism. Money and business had become the gods of the age.

A state as the “guardian and defender of culture; a state as the means of achieving the true goal of existence, not as a goal in itself; a state that is built on the Volk—that, Nietzsche would have accepted,” the newspaper claimed. Therefore, the philosopher “would have agreed with today’s [National Socialist] German idea of the state with all of his heart.”

Under the Weimar Republic, the Völkischer Beobachter complained, Nietzsche had been invoked far too frequently by “international-democratic literati” as a “star-witness” for their worldview. But, the paper countered, Nietzsche “hated and fought every form of democracy, both political and spiritual,” and he said so in the sharpest possible terms. The notions that “all are the same” and that at base we are all just selfish brutes and riffraff—were symbolic of the democratic age that believed in the equality of men and that established “the weak, fat, and cowardly as standards for this equality.”

In Nietzsche’s opinion, said the Völkischer Beobachter, this rule of the humble amounted to a blow against life itself. Against the democratic and supposedly feeble outlook of the Weimar era, the newspaper argued, Nietzsche set forth a way of thinking that sets laws for the future—an outlook which “handled contemporary things harshly and tyrannically” in the interest of the future.

Thus did the cultural-historical material that appeared in the Völkischer Beobachterresound with the Führer/Artist–Artist/Führer theme that typified Nazi cultural politics. Hitler was the primary manifestation of this creative leadership, but he came, according to this view, after a long line of notable predecessors, including Luther, Beethoven, Wagner, and, yes, Nietzsche.

Cultural renewal in accordance with such perceptions of intellectual history was a central premise of the larger project of the Third Reich, fundamental to Hitler’s aims. But this agenda also contributed to the most destructive impulses of the movement. Indeed, German cultural identity as shaped by the Nazi regime did not merely justify anti-Semitism or policies of extermination, it led to them. Hitler’s racist standards of judgment were grounded in cultural terms, as he stated in Mein Kampf: “If we were to divide mankind into three groups, the founders of culture, the bearers of culture, the destroyers of culture, only the Aryan could be considered as the representative of the first group.” According to the Völkischer Beobachter, Jewish creators such as Heine, Meyerbeer, Mendelssohn, Mahler, and Schoenberg—among many others—supposedly belonged in the latter, so they and their kind had to be eradicated.

Demonstrating that great cultural figures of the past would have agreed with these premises was a priority in the Nazi newspaper. One contributor put it in these stark terms: “to win over to our movement spiritual leaders who think they see something distasteful in anti-Semitism, it is extremely important to present more and more evidence that great, recognized spirits shared our hatred of Jewry.”

In the case of Nietzsche, however, this process required a little more “spin” than the “selective scavenging” for biographical and textual evidence that scholar Steven Aschheim identified as the usual mode of such politicization. Some Völkischer Beobachter contributors recognized that Nietzsche had not been a committed anti-Semite, and had even criticized the anti-Semitic views of Richard Wagner, his own sister, Elisabeth, and her husband, Bernhard Förster. One editor, for instance, said about Nietzsche: “His work contains other crass contradictions and obscurities, especially in his treatment of the Jewish Question, where he sometimes confesses himself as an Anti-Semite, and then as a philo-Semite. Equally obscure is what he understood as race and nation. This may be a result of the eruptive nature of his creativity and the shortness of his life, which didn’t allow him enough time to go into these issues deeply.”

But other contributors wrote as if aligning Nietzschean ideas with Nazi anti-Semitism posed no difficulties at all. One article listed carefully selected passages from Beyond Good and Evil to show that Nietzsche “expressed himself extraordinarily farsightedly on the Jewish Question.” An article entitled “Nietzsche as Warner about the Jewish Danger” insisted that Nietzsche concerned himself with the Jewish Question, “as every clear thinking, every sensitive Aryan-German person must.” Nietzsche, the paper said, recognized the danger threatening Germans in the form of a completely foreign and utterly different race, and “warned us—and like so many hundreds of great, significant men who warned us before him, he warned in vain!”

Nietzsche, this article went on, saw how the Jews were becoming “ever more powerful” in Germany and Europe and expressed this in “prophetic words.” Above all, the thought that the Jews “were determining what distinguishes”—in other words, that Jews had become important cultural arbiters—filled him with fright. For he knew that this would lead to a transvaluation of values, favoring “the development of the Jewish race, Jewish culture, and Jewish spiritual life—against German essence, German nature, and German culture.” He saw a foreign race operating at the cost of his own German Volk; and to Nietzsche—“the man of action—it was incomprehensible that the whole German Volk wasn’t arming itself with every weapon in order to save that which is most sacred, its volkish essence.” Was Nietzsche an anti-Semite? the article asked rhetorically. “He was—he was in the most intrinsic, pure and sacred sense of the word!”

National Socialist invocations of historical figures were intended as symbolic indications of what the New Germany would become. As Michaud put it, “the awakening into the myth” was “an awakening to the present”—a “recapitulation of the past directed toward the future.” Citing Baldur von Schirach was an excellent way for Michaud to support this point. The future Hitler Youth leader stated, “The perfect artists Michelangelo and Rembrandt, and Beethoven and Goethe, do not represent an appeal to return to the past, but show us the future that is ours and to which we belong.” The Völkischer Beobachter cultural section was clearly designed for the same reasons.

According to its longtime editor-in-chief, Alfred Rosenberg, the “German spirit” that inspired Nietzsche and about which he spoke with great hope had reawakened after the “darkness of the betrayal in 1918” in “the spirit of the Nazi Party.” Therein, Rosenberg wrote (in his cryptic style), “a new idea of life” and a worldview that recognized the laws of this life came reverentially into light. In their own time, Rosenberg continued, “National Socialists were experiencing the effects of the forces that became a dangerous, destructive power in the nineteenth century and continued to threaten Europe as a “great outbreak of the most dreadful illness.” Nietzsche “stands with us” and Nazis “greet him as a close relative in the formulation of a broadminded worldview, as a brother in the battle for the rebirth of a great German spirituality; as a herald of a European unity, and as a promoter of creative life in our ancient, yet—through a great revolution—rejuvenating continent.”

Similarly, Alfred Bäumler, who had been appointed Professor of Philosophy at the University of Berlin largely on the basis of his Nazified Nietzsche interpretations, wrote in the Völkischer Beobachter that the Volk which produced Nietzsche “was the only one that saw the greatest of all dangers threatening mankind.” Nazis alone—in contrast to their enemies, who were “reviling the great thinker”—honored the philosopher who “wrestled a new, pure image of man out of confusion and degradation.” Nietzsche, according to the leading Nazi Nietzschean, “foresaw and loved the idea we are protecting—that of the man whose innermost seed is bravery, the mother of all virtues; the man who believes: ‘That which does not kill us, makes us stronger.’”

Michaud made it clear that Nazi obsession with the cultural historical past was not a retrogressive “move,” but a forward-looking call for action. The appropriation of the German tradition of Kultur was “quite the reverse of the work of mourning.” It was a “process of reminiscence that asserted itself as faith in one’s own power to reawaken the lost object”—that is, to “produce the New Man.” The Völkischer Beobachter’s identification of Nietzsche as having “foreseen and loved” the New Man of Nazism was utterly consistent with this theme—in fact, a culmination of National Socialist self-validation.

Ultimately, production of these Nazi “ideals” involved going to war. Given the horrible outcomes of Nazi military policy, it is natural to assume that the Second World War itself was the primary goal of the regime. But war itself was not the aim. It was a means to an end. And that end was the realization of the new German man in a renewed nation, modeled on an image of Germany as Kulturnation—postulated and popularized, in part, by Völkischer Beobachter cultural coverage.

The newspaper trumpeted that the average German had to prepare again for battle—and invocations of Nietzsche were common in these warnings. As one contributor put it: “In the name of all conscientious front soldiers,” every “shirker” should read the words of Nietzsche carefully. Visiting Nietzsche’s grave, another claimed that he heard emitting from the site exhortations that Germans steel themselves for approaching conflict.

Don’t you hear anything? Is that not his voice, speaking to us: we who fight and create! “I want to say something to you, my brothers in spirit! Life means fighting and suffering. Sorrow makes some weary and soft—but it strengthens the creator. Think of the fates of a Michelangelo, a Beethoven and a Friedrich the Great—then you will know how love and toughness can be strangely connected in man. Know love, but stay tough for me!”

In addition to reports of ghostly commands, the paper insisted on a view of Nietzsche as militarist, “because one cannot conceive of sharper opposites than Friedrich Nietzsche and pacifism, Marxism, and egalitarian b.s. in general!” “What,” the paper asked, “would he say to a phrase like ‘No more war’?”

Peace—that is, the ultimately stable realization of Nazi ideals—could only be achieved through “battle” and “victory.” Elsewhere, the Völkischer Beobachter stipulated that Nietzsche constantly repeated that “struggle rules throughout nature—that life itself is an outcome of war.” Nietzsche, in this view, “valued battle as the basis for all life—so much that he cried, ‘Good old war sanctifies everything!’”

Völkischer Beobachter readers were exhorted, therefore, to live by Nietzsche’s teachings by either applying their own will to power or by willfully accepting fates determined by the National Socialist community. In this way, the paper smoothed out another difficulty that Nietzsche’s ideas held for Nazi ideology: Individuals could demonstrate their will to power not by becoming creative leaders alone, but alternatively by “accepting the necessity of things,” becoming a “part and tool of great world events,” and even making the ultimate sacrifice—the “highest self-denial”—for one’s Volk. In the years that Germany was gearing up for war, this reading of Nietzsche’s concept of will to power was most appropriate for Nazism’s militaristic plans.

The Völkischer Beobachter was ultimately designed to motivate action in this war, and regularly called on Nietzsche as a major source of inspiration in the struggle once it started. “What makes Nietzsche so valuable today,” it proclaimed, is his “fearless acknowledgement of the strong personality that alone can lead toward redemption, and after which all the suffering millions yearn.” Not only in Germany, but throughout Europe, “we address him as the preacher of action!” To “treat oneself harshly and tyrannically for the sake of the future of our Volk, that was one of the most important National Socialist requirements. “How often do we recite, in small gatherings, the words of [Nietzsche’s] Zarathustra: ‘And if ye will not be fates and inexorable ones, how can ye one day—conquer with me? . . . For the creators are tough.’” Toughness, “for the sake of our Volk!”—that was what the Völkischer Beobachter felt readers should derive from Nietzsche in wartime.

As the Völkischer Beobachter covered it, in a 1944 memorial event on the occasion of Nietzsche’s one hundredth birthday, Alfred Rosenberg gave a speech which even more directly (though still cryptically) associated him with twentieth century warfare. The National Socialist movement, according to Rosenberg, “stood as a unified whole against the rest of the world, just as Nietzsche stood as an individual against the violent forces of his time.” The world of “despicable financiers and their henchmen, the passion whipped up by millions of envious Bolsheviks, the destructive work driven by the rage of the Jewish underworld, this all appeared shortly before the enormous purifying wave [i.e., Nazism] from the heart of Europe began to flow.” Now, as Nietzsche had done alone, the “National Socialist pan-German Empire stood as a block of will” in the middle of this tremendous struggle, “serving in full consciousness the necessity of a great life”—the necessity of, in Nietzsche’s phrase, a “European destiny.”