Count Harry Kessler received the news in the officers’ mess of his army regiment from a fellow officer going through dispatches. On August 25, 1900, Friedrich Nietzsche, who had famously announced the death of God, had himself died.

During the previous decade, Nietzsche’s writings had taken German culture by storm. One of Kessler’s friends joked that “six educated Germans cannot come together for a half hour without Nietzsche’s name being mentioned.” Nietzsche had become a hero—and cult figure—to those who wanted to reimagine Germany; and a villain to those who remained attached to Germany’s Protestant roots and traditional order.

The philosopher’s tragic decline only added to his mystique. Nietzsche had suffered a major mental breakdown in 1888, just as his ideas were catching fire outside of academic circles. The once brilliant scholar and philosopher, reduced to the mental cognition of a child, had no understanding of how famous he’d become.

As Nietzsche’s ideas were being adapted to various and contrary ends by avant-garde artists, psychoanalysts, and racial ideologues, his death provoked a battle over his legacy. Kessler, a prominent patron of culture and a well-connected operator on the European art scene, took part in the fight.

The count was a man of voracious intellect and endless charm, as well as a deeply committed diarist. At the age of twelve he started keeping a journal, creating a treasure trove for historians writing about the artistic forces of Wilhelmine Germany and the Belle Époque. Kessler seemed to meet or know everyone of importance—more than forty thousand names appear in fifteen thousand pages written over fifty-seven years. With the discipline of a great reporter, he recorded countless remarkable moments that describe, in intimate detail, the seismic political shifts that rocked Europe from the turn of the century to the Third Reich. Laird M. Easton, Kessler’s biographer, has edited and translated selections from the count’s early years to create Journey to the Abyss: The Diaries of Count Harry Kessler, 1880–1918 (Knopf). Nestled among its many stories is Kessler’s encounter with the life and legacy of Nietzsche. When Kessler was a young man, Nietzsche’s writings provided him with a framework for thinking beyond the staid categories of his bourgeois upbringing. Over time, Kessler fashioned himself first into a remarkable aesthete and later a diplomat and a spy. W. H. Auden, who considered Kessler a friend, called him “probably the most cosmopolitan man who ever lived.”

In the years leading up to the First World War, Kessler channeled his organizational talents into designing and raising money for a memorial to honor Nietzsche. But he wasn’t the only one with a keen interest in the philosopher’s legacy. Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche, the philosopher’s sister, had her own ideas about how her brother’s work and life should be used.

THE LIVES AND LOVES OF FRITZ AND ELISABETH

Close in age, Fritz (as he was known to friends and family) and Elisabeth shared a bond made all the stronger by the loss of their father, a Lutheran minister, who died in 1849, when Fritz was four and Elisabeth was three. As the boy, Fritz received a fine education, one that encouraged his interest in literature and music. In 1864, he enrolled at the university in Bonn, switching to Leipzig the following year, leaving Elisabeth behind with Franziska, their domineering mother. Fritz’s studies and exposure to the wider world led him, in another sense, away from his sister and his family. He came to question the place of God and religion, and then abandoned theology in favor of philology. His disenchantment with Christianity caused the first of many rifts with Elisabeth, who found his rejection of their father’s faith disconcerting.

In 1869, after a riding accident cut short his military service, Nietzsche accepted a position teaching classical philology in Basel, Switzerland. That same year, he met composer Richard Wagner. Despite an age difference of three decades, the two men forged an intellectual connection through their love of music and an appreciation of the philosophy of Arthur Schopenhauer. In The Birth of Tragedy, published in 1872, the young thinker argued that western culture had reached its pinnacle under the Greeks, but Wagner’s operas had come closest to embodying the Greek tradition in modern terms.

Fritz’s health had never been robust and his mania for work frequently left him spent and vulnerable to illness. His body was also slowly being consumed by syphilis, which he had contracted from a prostitute. Worried by letters recounting migraines and stomach problems, Elisabeth journeyed to Basel in 1870 to care for her brother. Over the next eight years, she spent long stretches managing his household so that he could teach and write.

Fritz’s relationship with Wagner, over time, assumed a father-son dynamic—and the son began to chafe at the father’s overbearing influence. After attending the Bayreuth Festival, inaugurated in 1876 to celebrate Wagner’s music, Fritz experienced a conversion: Wagner’s operas were not the reawakening of Greek culture as he first thought, but spectacles pandering to the basest impulses of the newly unified Germany. He also had doubts about Schopenhauer’s pessimism and the anti-Semitism that permeated Wagner’s worldview.

In 1878, Nietzsche published Human, All-Too-Human, which featured a critique of Christianity and anti-Semitism. The book upset Elisabeth, who was distraught that Fritz may have made her persona non grata to the Wagners and their social circle. The strain led Elisabeth to abandon her brother and return to Germany. Unable to maintain his own household, Nietzsche resigned his post at Basel and became an itinerant philosopher.

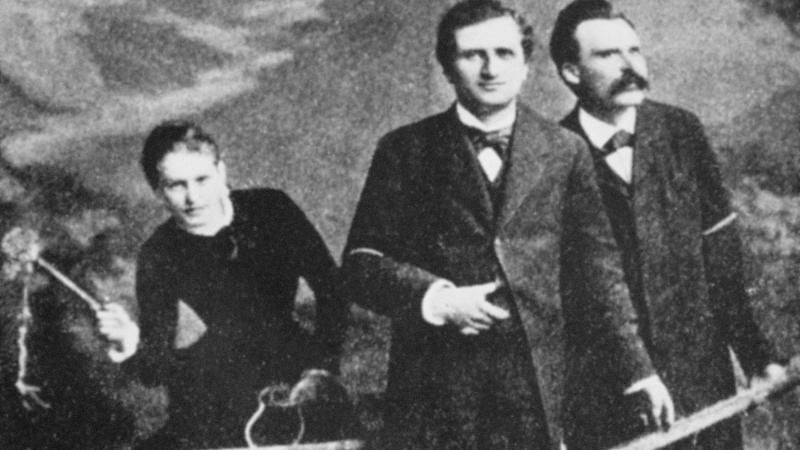

Next, the siblings began to quarrel over each others’ love lives. In 1882, at the age of thirty-seven, Fritz fell hard for Lou Salomé, a twenty-one-year-old Russian who was as smart as she was beautiful. Fritz found her mind intoxicating, relishing their never-ending philosophical discussions. Elisabeth, who prized respectability and was fiercely protective of her relationship with Fritz, regarded the unconventional Salomé as a threat. She objected to Salomé’s plan for a “philosophical convent,” in which Salomé, Fritz, and philosopher Paul Rée would create a platonic household. And she cringed with mortification when Salomé shared a photograph—one that depicted Salomé, whip in hand, driving a cart pulled by Fritz and Rée—with their social circle.

In Friedrich Nietzsche: A Philosophical Biography, Julian Young suggests that Nietzsche staged the scene as an homage to the enslavement of both him and Rée to Salomé’s charms. The photograph also serves as the inspiration for the notorious remark in Thus Spoke Zarathustra: “Do you go to women? Don’t forget the whip.”

Angry at his sister’s meddling, Fritz accused her of “dirty and abusive” behavior. Fritz had his own issues with Elisabeth’s engagement to Bernhard Förster, a leading figure in Germany’s anti-Semitic political movement. In 1881, Förster masterminded an unsuccessful petition drive demanding that the government register all Jews, limit Jewish immigration, and ban Jews from teaching. When Förster’s political activities cost him his teaching job, he decided to pour his energy into launching Nueve Germania, a racially pure German colony in Paraguay. While initially skeptical of Förster’s radicalism and his colonial project, Elisabeth came to embrace his ideas, finding them more palatable than her brother’s rejection of God. By 1884, the siblings ceased to speak to each other. “This accursed anti-Semitism . . . is the cause of a radical breach between me and my sister,” Nietzsche wrote a friend.

Over the course of the next year, they reconciled. Elisabeth even asked Fritz to serve as best man at her wedding. He refused—standing up at the ceremony meant endorsing the marriage, something he couldn’t do. Elisabeth married Förster on May 22, 1885, the anniversary of Wagner’s birthday. At the end of October, Fritz wished Elisabeth well before she departed for Paraguay, secretly happy to put both physical and philosophical distance between himself and Förster. It was the last time Elisabeth saw her brother in his right mind.

By 1888, Nietzsche was becoming remarkably well known. The University of Copenhagen hosted a series of lectures about his philosophy, and translations of his key writings were in the works. So promising was the outlook that he made inquiries about buying back his oeuvre from his publisher.

But most of his fame lay abroad, he complained: “In Vienna, in St. Petersburg, in Stockholm, in Copenhagen, in Paris, in New York—everywhere I have been discovered; but not in the shadows of Europe, Germany.”

In early 1889, he collapsed, his body exhausted from almost two decades of battling syphilis. When he regained consciousness, the philosopher declared himself to be the reincarnation of Dionysus. It was not an ironic philosophical proclamation, but the desperate cry of a faltering mind. It was the end of his intellectual life, and the beginning of his immortality. But as Friedrich Nietszche and the nineteenth century entered their final years, German readers began to embrace the works of this native son.

“A great deal of the magic lay in the lyricism, beauty, and power of Nietzsche’s language. The philosopher was a German thinker with German roots addressing what were thought to be largely German problems,” writes Steven E. Aschheim in The Nietzsche Legacy in Germany, 1890–1990.

Kessler was one of those enraptured by the magic. Born in Paris in 1868 to a Hamburg banker and a British heiress, he spent his childhood straddling Victorian Britain and Wilhelmine Germany. The nationalist fervor of the late-nineteenth century, in combination with pressure from his father, made it impossible to be a citizen of Europe, as the sensitive young man would have preferred. Faced with the prospect of becoming a banker, Kessler this time asserted himself and convinced his parents to let him study law and art history at Bonn and Leipzig. When it came time to fulfill his military service, he secured a spot in the elite Third Guard Lancers.

Through his studies, Kessler developed an interest in ancient Greece, an appreciation of art and aesthetics, and a disdain for historicism, making him an ideal reader for Nietzsche’s writings. At the end of 1891, a friend lent him a copy of Human, All-Too-Human. Kessler wasn’t immediately smitten. His diary entries find him contesting Nietzsche’s explanation of schadenfreude and observing that the philosopher’s hatred of everything German had “led him to utter absurdities,” such as divorcing Goethe’s accomplishments from German culture. But Kessler’s skepticism soon waned.

Uncertain of what career path to take, Kessler found solace in Nietzsche’s dictum that “the world is only justifiable as an aesthetic phenomenon.” As he embarked on a trip around the world in 1892, he packed Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Nietzsche’s meditation on how to achieve a “superhuman” state. Kessler read it, along with the Odyssey, on a voyage between San Francisco and Yokohama.

THE MADMAN IN THE ARCHIVE

After five years in Paraguay, Elisabeth returned to Germany in 1890, arriving not as a triumphant first lady, but as a disgraced widow. Accused of mismanaging Nueve Germania and stealing from its inhabitants, Förster had shot himself rather than endure the humiliation of bankruptcy and possible jail time. “False friends and the intrigues of enemies broke his heart,” Elisabeth explained, insisting that her husband had not taken his own life but instead had died from a heart attack. Having already born the loss of her husband, Elisabeth found that she had two brothers: the philosopher being devoured by Germans like Kessler, and the madman haunting the halls of their childhood home.

Rather than stay and help her mother care for her brother, Elisabeth returned to Nueve Germania, determined to carry on Förster’s work and revitalize his reputation, only to face charges of mismanagement herself. Leaving a trail of creditors in her wake, she fled back to Germany and embraced her identity as Friedrich Nietzsche’s sister. No longer would she be Elisabeth “Eli” Förster, but rather Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche, the name change made permanent by court order.

Stuck under her mother’s roof in the small town of Naumburg, Förster-Nietzsche channeled her energy into establishing an archive of her brother’s works and began the process of deciphering what else could be published from his papers. Given Förster-Nietzsche’s indifferent education and contradictory views, she was not an ideal custodian. But as she had physical possession of Nietzsche’s papers, there was little his friends could do. Anyone who had business with Nietzsche’s papers and his legacy had to go through Förster-Nietzsche.

On October 26, 1895, Kessler paid a visit, meeting her for the first time. Kessler had become a member of the editorial board of Pan, an illustrated journal devoted to literature and modern art, and wanted to publish Nietzsche’s musical compositions. “She is a small, delicate, still pretty woman, with a fresh complexion and tresses; her appearance does not indicate her energy,” he wrote in his diary. The archive, which housed Nietzsche’s books and manuscripts, was a “medium-sized, friendly room.”

Over lunch and dinner, Förster-Nietzsche educated him about her “unpleasant” situation. “She says that no one here has the slightest interest in, or understanding of her brother. She maintains her earlier connections to the old retired officers and civil servants but is not thanked for her advocacy of Nietzsche’s interests and thoughts, at most only forgiven. Even their own mother, an old pious pastor’s wife, is, in her sentiments, among the enemy.” While leery of Förster-Nietzsche, Kessler left the meeting an ardent supporter of the archive and agreed to help however he could.

Förster-Nietzsche had never lacked for ambition and her brother’s growing fame became a vehicle for it. In 1896, she wrested control of the copyright for his works from their mother and moved her brother to Weimar, a sleepy town regarded as the cradle of German culture. There, she could position him as the equal of Goethe and Schiller.

In August 1897, the Nietzsches moved into Villa Silberblick, a four-story house that was an easy walk from the center of Weimar. The villa was purchased for them to use by Meta von Salis, a Swiss aristocrat who had befriended Nietzsche when he lived in Zurich. Captivated by her fine manners and high German accent, Nietzsche had overlooked Salis’s advocacy of women’s emancipation, an issue for which he had little fondness. “She, in turn, was bowled over by him—the encounter, she said, cast a ‘golden shimmer’ over the rest of her life, a life during which she never abandoned the cause of promoting his philosophy,” writes Young.

Not long after the Nietzsches took up residence in Villa Silberblick, Kessler stopped in. “The house lies on a hill above the city in a newly planted but still rather bare garden,” he wrote in his diary. Förster-Nietzsche told him that her brother liked the new house—upon arriving he had wandered from room to room chanting, “palazzo, palazzo.” That story and other tales of Nietzsche’s behavior unsettled Kessler. “She seems to have become so accustomed to treating her brother as a stammering child that she no longer seems to feel the horrible tragedy of it all.”

It also appears to be the first time that Kessler encountered Nietzsche—to use the word “met” would be misleading.

He lay sleeping on a sofa. The mighty head rested, as if too heavy for his neck, sunk on his chest, hanging halfway to the right. The forehead is quite colossal, the mane of his hair still dark brown, and also the shaggy, swollen moustache. There are wide, black-brown shadows sunk deep under his eyes into his cheeks. In his flat, loose face deep furrows from thought and desire are engraved but gradually fading and becoming smooth again. The hands are like wax, with greenish-violet veins, and somewhat swollen, like those of a corpse.

Despite Förster-Nietzsche stroking him and calling him, “darling, darling,” the philosopher failed to wake. “Thus he resembles not someone sick or crazy but rather a dead man,” wrote Kessler.

After dinner, Förster-Nietzsche offered Kessler the job of editing new editions of Zarathustra and collected poems, but Kessler demurred, offering instead to oversee the design and printing.

As always Kessler was making mental notes. He wasn’t impressed with how the house had been decorated, calling it in his diary “prosperous, but decorated without refinement.” Förster-Nietzsche apparently felt the same way and embarked on a series of expensive renovations, sending the bill to Salis for payment. Outraged at Förster-Nietzsche’s “increasingly reckless arrogance,” and fueled by a nasty exchange of letters, Salis broke off contact. Wanting nothing more to do with Förster-Nietzsche, she sold the villa to a Nietzsche cousin in 1899. With a twinge of regret, Salis joined the ranks of Nietzsche’s friends and admirers who worried what would become of Nietzsche’s legacy so long as it was in the custody of Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche.

THE MASK OF DEATH

Kessler arrived home from reserve duty to find a telegram waiting. “This morning my deeply loved brother passed away unexpectedly,” wrote Förster-Nietzsche. “Monday afternoon at 5 p.m. the funeral in the Nietzsche Archive. Please come if possible.” There was no “if” about it. Kessler booked a train ticket to Weimar for the next day. When he arrived, he found that Förster-Nietzsche was “very upset.”

Nietzsche’s body had been laid out in a coffin lined with white damask and linen, his half-opened eyes suggesting he was merely sleeping. “His last sickness gave him a pitifully drawn and emaciated expression, but the large, puffy, frost-gray moustache hides the pain of the mouth,” observed Kessler. “And this splendid form appears everywhere through the emaciation: the wide, arched forehead, the robust, powerful jaw and cheekbone appear still more sharply under the skin than when he was alive. The total impression is one of strength despite the pain.”

The idea of memorializing Nietzsche in some manner must have already been on Kessler’s mind. On the morning of the funeral, he arranged for a death mask to be made. To help him, Kessler recruited Curt Stoeving, who had painted the philosopher’s portrait some years earlier, and a local plasterer. They were done in a half hour.

At five o’clock, mourners packed the archive, bodies crowding the coffin. Candles blazed and a women’s choir sang Brahms and “a magnificently tragic motet.” There was also a long eulogy by art historian Kurt Breysig, who offered a cultural-historical analysis of Nietzsche’s work. “Seldom have I experienced a grimmer moment,” wrote architect Fritz Schumacher, who attended the service. “Scholarship pursued this man to the grave. If he had revived he would have thrown the speaker out of the window and chased us out of the temple.”

The following day, Nietzsche was buried next to his parents in the graveyard of the church in Röcken, where his father had served as a pastor. It was contrary to his wishes—he had wanted to be buried in Switzerland on the Chasté peninsula in Sils-Maria, where he had spent so many pleasant summers. “What was Nietzschean in the service was the sunny stillness of this natural solitude: the light playing through the plum trees on the church wall and even in the grave; a large spider spinning her web over the grave from branch to branch in a sunbeam,” wrote Kessler. Otherwise, it was a Christian affair for a man who did not believe in God: the bells rang, a choir sang spirituals, and a silver cross lay on the coffin. In the running debate over religion between Förster-Nietzsche and her brother, she had the final word.

MEMORIALIZING NIETZSCHE

As the new century inched forward, Kessler found himself drawn to Weimar for reasons other than Nietzsche. His dear friend, Belgian architect Henry van de Velde, had become director of Weimar’s arts and crafts school in 1902. There were those in the court of Wilhelm Ernst, the Grand Duke of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach, who longed to see Kessler in Weimar as well. For a man who thrived on the cultural frisson of Berlin and Paris, the decision to ensconce himself in a town of thirty thousand, populated by retirees, was not undertaken lightly. But the offer of an honorary directorship of the Museum of Arts and Crafts was hard to refuse and Kessler took up the post in March 1903.

Kessler had grand plans for turning Weimar and the museum into a center for aesthetic modernism. He organized a series of exhibitions that promoted symbolist artist Max Klinger, French postimpressionism, and English book and theater design. Kessler also bought a house in Weimar, enlisting van de Velde to design the interior, and collaborated again with him on plans for the construction of a new theater.

Assembling the pieces of his vision led Kessler to spend long stretches in London and Paris, meeting with artists and dealers. In February 1905, during one of his Paris sojourns, Kessler approached Auguste Rodin about doing a bust of Nietzsche. The artist was reluctant to take the commission, citing the “great difficulty of doing someone whom he had never seen alive.” Kessler assured him a death mask had been made, which seemed to cheer him, but Rodin still balked. “The bone structure, that’s already something, it’s the foundation of all we do,” Rodin told Kessler. “But beyond that there is the movement of the surfaces that one must observe, the principal direction of the movement of the muscles on the bone structure that one can only observe with a model. . . . When one has the movement, one has everything.”

Kessler’s modern ideas about art soon clashed with the more traditional ones held by Weimar society. In 1906, he was forced to resign his post after an exhibition of watercolors of nude women by Rodin caused a scandal. Kessler quickly moved on to other projects, such as becoming a patron of artists whose work he admired. He also collaborated with composer Hugo von Hofmannsthal for the libretto for Der Rosenkavalier, an opera composed by Richard Strauss.

Förster-Nietzsche had not been idle either. She enlisted van de Velde’s services to redecorate and extend the archive in 1903 (it remains a showcase of art nouveau design). In 1908, she formed the Nietzsche Archive Foundation, which formalized its operation. Kessler was given a seat on the board. The money to operate the archive came from Ernst Thiel, a Swedish businessman of Jewish descent. Förster-Nietzsche played down her anti-Semitism to win his support.

A steady stream of Nietzsche’s collected works and letters had also appeared under Förster-Nietzsche’s direction, with more on the way. The volumes are riddled with forgeries large and small. Scholars who later tried to reconcile the content of the volumes with the archival record have noted the lack of originals for many letters, particularly in the correspondence between Förster-Nietzsche and her brother during her time in Paraguay. Förster-Nietzsche also wasn’t above changing the identity of letter recipients or altering the text to soften her brother’s rants against anti-Semitism.

Did Kessler know about the sleight of hand? His diary is silent on the matter, and Easton, his biographer, isn’t sure either. “Whether Kessler, before the war, ever suspected how Elisabeth was deliberately distorting her brother’s legacy to suit an anti-Semitic, nationalist interpretation, is unclear,” he writes.

Planning for a memorial progressed in fits and starts until 1911. Förster-Nietzsche began to push for its completion in time to celebrate her brother’s seventieth birthday in 1914. But how does one memorialize a philosopher, especially one who wrote deeply about art and had a poor opinion of contemporary art forms? Förster-Nietzsche imagined a “modest temple.” It is revealing that she thought a temple appropriate as long as it was not “gigantic,” for which there might not be sufficient funds. Ever the architect, van de Velde argued for remodeling the existing archive by adding a great hall that incorporated a memorial.

Kessler also wanted a temple, one that would embody the ancient Greek principles that infused Nietzsche’s worldview—and he had already mapped it out in his head. In a nod to Apollonian principles, the courtyard would feature a statue of a naked youth carved by Aristide Maillol, a French Catalan sculptor known for his classical forms. The interior would invoke Dionysus, with a bust of Nietzsche and bas reliefs by Klinger. Nietzsche quotations engraved by Eric Gill, a British artist with a flair for typography, would adorn the walls.

The assembling of different artists in service of a larger project was pure Kessler. He could also be incredibly persuasive. By the end of their first meeting to discuss the project, van de Velde and Förster-Nietzsche had signed on to his vision.

Building the temple required money, somewhere in the range of fifty thousand marks. Kessler and the others decided to offer subscriptions, which would start at one thousand marks (Kessler committed five thousand), and to publish facsimile editions of Nietzsche’s writings. Kessler also envisioned benefit performances, lectures, and concerts in Germany, France, Austria, and New York. The informal committee soon morphed into a formal board, with Kessler as president. Förster-Nietzsche, however, did not have a spot on the board. Easton speculates that Kessler might not have offered her one, fearful of giving her too much influence.

When Kessler ventured to Paris in the spring, he talked up plans for the memorial among his social circle, which included poet Rainer Maria Rilke, the writer Jean Cocteau, theater promoter Gabriel Astruc, composer Reynaldo Hahn, and Ballet Russes founder Sergei Diaghilev. He encountered both enthusiastic support and studied opposition. Painter Pierre Bonnard refused to support the project. “It’s because I am, in a certain sense, opposed to Nietzsche, not to his ideas, but to his person,” Bonnard told Kessler. “I am a little afraid of those beings that are nothing but thought. It seems to me that they will finish one day with their thinking by being devoured by life.”

Over lunch, Kessler asked dancer Vaslav Nijinsky, the toast of Paris for his performances with the Ballets Russes, to act as the model for Maillol’s sculpture. Nijinsky agreed, but Maillol objected. “Have you seen him naked?” Maillol asked Kessler. “Isn’t he round? What is beautiful for others is not often for the artist who has an idea in his head. The model must respond to the idea that the artist wishes to execute.” One evening of watching Nijinsky dance changed Maillol’s mind. “He’s absolutely Eros,” he told Kessler. “He’s so perfect that he is almost too beautiful.”

Building a temple was an ambitious but manageable project—then came the idea for the stadium. Writing to Förster-Nietzsche, Kessler begged her not to be frightened of the idea. “Your brother was the first . . . to teach joy in one’s body, on physical strength and beauty; the first who brought physical culture, force, and grace back into relation with the spirit and the highest things.” Kessler found support for the stadium idea among the other board members, who grasped that gymnastic clubs and sport leagues would help finance its construction.

Förster-Nietzsche was both “excited and horrified” by the idea of the stadium—and accused Kessler and van de Velde of working behind her back. “Basically she is a little philistine, pastor’s daughter, who swears to be sure upon the words of her brother, but is upset and angry as soon as you try to transform them into deeds,” wrote an exasperated Kessler. “She justifies much of what her brother said about women. She was in fact the only woman he knew intimately.” Putting his vitriol aside, Kessler met with Förster-Nietzsche, soothing her paranoia by explaining how the stadium idea had come about.

By September, Kessler had found a stretch of suitable land. Now it was up to van de Velde to design the ceremonial approach, temple, and stadium. Kessler estimated that the final price tag would run close to one million marks. “If we have more money or raise enough, I would like to create, next to the Nietzsche Memorial, an Institute for ‘Genetics,’ for the beautification of the race,” wrote Kessler.

In mid-October, Förster-Nietzsche once again kicked up a fuss about the project. “Unbelievable letter from Förster-Nietzsche, who asks me to give up the plan for the memorial because ‘a Herr Lenke or Menke’ (she cannot recall the name) visited her and spoke against the project,” wrote Kessler. “The ‘forthright indignation’ of this ‘Nietzsche worshipper’ has affected her deeply, and ‘she herself cannot do anything now other than to oppose it.’” The project wasn’t so easily abandoned. Kessler had arranged for a loan of sixty thousand marks to purchase the required property, the money provided by two Jewish bankers. He sent Förster-Nietzsche a terse letter explaining that the loan would have to be paid back, well aware that she lacked the funds to do so. Kessler also suggested that she refrain from valuing the opinion of a man whose name she couldn’t remember.

At the end of November, Kessler met with van de Velde to see the plans. Kessler was greatly disappointed. The design reminded him of “an English country home”—and he worried that his old friend was out of his depth. “His imagination falters without the aid of utility. Clearly he hasn’t much heart for the job.” Van de Velde went back to his drafting board and presented a new design two days later. “Now the temple looks like a municipal museum, just a lot of little gossipy forms, unimportant things, cloak rooms, a hall with skylights, etc.,” wrote Kessler. “I told him that we can’t continue this way.”

Kessler followed up their meeting with a letter that attempted to describe what he wanted the monument to achieve. First and foremost, it was “the transposition of the personality of Nietzsche into a grand architectural formula”:

A light monument, soaring, so to speak, on its heights before the massive stadium, an almost aerial monument, like certain Italo-Muslim monuments of the Indies that appear constructed by djinns, but nervous and strong and even slyly massive beneath this appearance of lightness, like the physiognomy of Nietzsche himself, with his formidable Bismarckian bone structure under the exquisitely delicate Greek surfaces of his brow and mouth. I would like not only joy but almost irony in the monumental expression of this opposition, the triumph of finesse over force. A complete orchestration of these two motifs leading to a joy and a serenity, an almost ironic purity and lightness.

The charge Kessler gave van de Velde was almost impossible to realize. “One sympathizes with van de Velde upon being told that he had to transform the physiognomy—let alone the ideas—of a philosopher into a building,” writes Easton.

In mid-December, van de Velde presented Kessler with a scale model of how a stadium and temple would look on the site they had chosen. “The stadium in this model has exactly the dimensions of the one in Athens,” wrote Kessler. “The whole, especially the relation of the temple to the stadium, was surprisingly beautiful, beautiful and grandiose.” But things would once again stall when it came to the temple.

“The truth is that our age lacks any tradition and handle on decorative architecture,” wrote Kessler. “This complete failure of van de Velde, after repeated efforts, to find an architectural expression for a pure and aimless joy in life and lightness proves it.”

In June of 1912, van de Velde presented his design for the Nietzsche memorial to the committee. Kessler’s diary is mum on why and how he came to support that particular design. The committee approved it, despite the revised estimate of two million marks needed to make it a reality.

For the remainder of 1912 and 1913, the memorial existed in limbo. Kessler was deeply involved in writing and producing a ballet, but Förster-Nietzsche’s ongoing financial troubles contributed as well. Her mismanagement of the archive had saddled it with a crushing debt and she didn’t like that money, which theoretically could help the archive, was going toward building the memorial. Kessler, she complained, “chases fantasy and it doesn’t occur to him that I have suffered cares and anxieties for twenty years and he could well come halfway to meet my wishes.” Eventually, Kessler and Förster-Nietzsche came to an agreement that securing the archive took precedence, effectively putting the memorial on hold until one hundred thousand marks could be raised.

FUTURE BELIEVERS

The advent of the First World War spelled the end of Kessler’s plans for the memorial, a development Nietzsche surely would have applauded. “I want no ‘believers’; I think I am too malicious to believe in myself; I never speak to masses.—I have a terrible fear that one day I will be pronounced holy,” he wrote in Ecce Homo in 1888.

Like many Germans, Kessler welcomed the war, relishing the opportunity to serve with his regiment on the front lines. “These first weeks of war have brought forth something from unknown depths in our German people, which I can only compare with an earnest and cheerful spirituality,” he wrote a friend. War on the eastern front proved less than uplifting, and Kessler swung a reassignment back to Berlin in 1916. From there he was posted to the German embassy in Bern, Switzerland, where he served out the war acting as a diplomat and a spy.

Förster-Nietzsche used the war to further distort her brother’s work, publishing a series of articles proclaiming that Nietzsche would have supported the war. It’s unlikely that Nietzsche, who regarded the creation of the Second German Reich in 1871 as the catalyst for the decline of German culture, would have done so. The German government also looked to Nietzsche for inspiration, printing 150,000 copies of Thus Spoke Zarathustrafor distribution, along with the Bible, to German soldiers at the front.

After the war, Förster-Nietzsche, who opposed the new Weimar Republic, joined the überconservative German National People’s party. As the 1920s progressed, she cultivated Nietzsche admirers with far-right political beliefs, especially if they could write a check to support the archive. “It is enough to make one weep to see what has become of Nietzsche and the Nietzsche Archives,” lamented Kessler in 1932.

There was also no more talk of a memorial, at least by Kessler. The milieu that had made such a grand scheme seem feasible had been destroyed by four years of trench warfare. The war also dulled Kessler’s taste for imperial ambition, turning him into a pacifist. Having discovered a talent for diplomacy, Kessler became Germany’s first ambassador to the newly independent Poland. Although Kessler traveled far and wide over the decades, he always returned home to Germany. The advent of the Nazi regime in 1933 made that impossible, both spiritually and intellectually. He lived out his five remaining years in exile in France.

Under the Third Reich, Förster-Nietzsche was showered with attention and accolades. The years she spent molding her brother’s work and memory to align with her right-wing beliefs had made him a hero to the Nazi leadership. Starting in May 1934, she began receiving three hundred reichsmarks a month from Hitler’s private purse in honor of “her services in preserving and publicizing Nietzsche’s work.” When she died in 1935, Hitler attended her memorial service.