“War is terrible and yet we love it,” wrote Drew Gilpin Faust in 2004. “War is, by its very definition, a story. War imposes an orderly narrative on what without its definition of purpose and structure would be simply violence. We as writers create that story; we remember that story. . . . We love war because of these stories. But we should ask ourselves how in the construction of war stories we may be helping to construct war itself.” With such probing insights, Faust has made a permanent impact on the writing of American history.

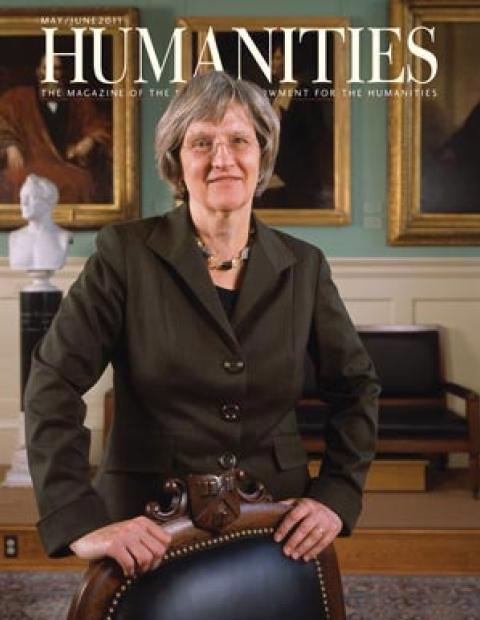

Faust is widely known today as an important American first—the first woman president of Harvard University. For this distinction, her remarkable career should be recognized and studied as a story of ambitious and graceful achievement. Since her appointment as Harvard’s twenty-eighth leader in its 375-year history, she has established a reputation as a skilled manager of people. Universities, and especially the humanities, are vital to the very survival of our civilization. President Faust represents that essential truth as a model, but the trajectory by which she became Professor Faust tells us even more about her as a person and a scholar.

Catherine Drew Gilpin was born into a prosperous Virginia family on September 18, 1947, and raised in Clarke County in the northern reaches of the Shenandoah Valley. Her father bred thoroughbred horses on their sprawling land and her mother brought her up to be a “lady.” But along with her three brothers, Drew preferred to get a great education, and to challenge the gender destiny and racial segregation with which she came of age. She came north for high school to Concord Academy, a girls’ prep school in Massachusetts, and then to Bryn Mawr, a women’s college outside Philadelphia, where she graduated in 1968. A year later, she entered graduate school in history and American civilization at the University of Pennsylvania, and achieved her PhD in 1975 at the tender age of 27.

Faust soon established herself as a historian’s historian—a scholar who logs endless hours in archives, and asks new and provocative questions that yield fresh and surprising insights, all captured in clear, sometimes even lyrical prose. Scholars and readers alike rightly tend to value most those historians who, like Faust, can make us think anew, and embed their research-based judgments in good narrative, as they also suggest the past’s inherent place in our present.

Drew Faust has been a pioneer in at least three distinct subfields of nineteenth-century American history: first, the intellectual history of the Old South, especially proslavery ideology; second, the history of women and gender; and third, the social and cultural history of the Civil War, particularly that conflict’s overwhelming scale of death and suffering. Faust has not merely contributed to historical knowledge or told old stories well. She has changed the questions and pushed the story in new directions.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, when Faust published her first three books—A Sacred Circle: The Dilemma of the Intellectual in the Old South, The Ideology of Slavery: Proslavery Thought in the Antebellum South: 1830–1860, and a biography, James Henry Hammond and the Old South: A Design for Mastery—she worked against a prevailing assumption that the slaveholding elite of the Old South produced no “intellectual history.” While the “mind of the South” had been a twentieth-century preoccupation of many writers and scholars, few had probed the disturbing and, to modern sensibilities, retrograde proslavery mind. But in the five Southerners who fashioned themselves a “sacred circle” of alienated intellectuals, the politician Hammond, the novelist William Gilmore Simms, the agricultural reformer Edmund Ruffin, and the college professors Nathaniel Beverly Tucker and George Frederick Holmes, Faust uncovered and humanized a cadre of book-toting critics of the society they were helping build. Their failed struggle to manage any permanent “institutionalization of intellect” turns out to be similar to those pursuing the life of the mind in many other eras and worlds.

Even more lastingly, Faust helped forge a new interpretation of proslavery ideology. Rather than ungraspable “odd” defenders of the twin evils of slavery and white supremacy alone, the myriad writers who fashioned an elaborate justification of slavery in the antebellum era were believers in an organically conservative, hierarchical worldview, manipulating the Bible, but also a theory of history and human nature to defend racial slavery as a vision of social order. Their views were rendered no less racist or abhorrent, but in Faust’s handling their defense of such a system of exploitation became comprehensible as rational thought. Moreover, in Hammond, Faust found a figure through which all the contradictions of the Old South flowed; he was a brilliant and handsome sexual predator who abused his slave women at the same time he argued for a blending of modernization and tradition in a society heading toward destruction.

For a young woman historian of her native region, these subjects were hardly the comfort zones of Southern history. By the 1990s, Faust rode the wave of women’s and social history into the South and the Civil War with yet more provocative results. In Mothers of Invention: Women of the Slaveholding South in the American Civil War, Faust deeply researched elite white women undergoing the brutal travail of war, revolution, and loss. She revealed in stunning detail how these women struggled against their fate, not as proto-feminists, but as women undergoing transformations for which they were psychologically unprepared. She also suggested a bold interpretation of why the Confederacy lost the war. Perhaps it was these very women, writing thousands of letters to their men at the front, who persuaded the soldiers, themselves fearful of the physical and social destruction on the home front, to give up the fight. Such an incendiary interpretation, directly contradicting both Lost Cause myths about women’s devotion to the Confederacy as well as military historians’ strategic interpretations, elicited much criticism at the time and since. Faust has somewhat modified her own stance. But the idea did provoke an important debate on an old question: Just why did the Confederacy, which had forged a genuine brand of “nationalism” (as Faust herself had argued in yet another book, The Creation of Confederate Nationalism) and a devoted army, collapse in defeat?

Mothers of Invention undoubtedly led Faust to her next major subject. In This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War, Faust wrote a withering and brilliant study of the scale and significance of the death of over 600,000 soldiers and uncounted thousands of white civilians and former slaves in 1861–65. In a mode both analytical and elegiac, Faust removed the veil from a subject that has never fit into the sentimentalized Civil War demanded by many enthusiasts. Americans, North and South, black and white, Faust demonstrated, could not achieve the “good death” of their fallen loved ones, since huge numbers of slain soldiers were never identified by name or even the location of their graves. Above all, in this book, Faust achieved a rare kind of historical writing: unforgettable descriptions of what we have not wanted to see in this story, intertwined with an interpretation of death on such a scale that in its incomprehensibility the Civil War generation experienced a loss of historical innocence from which each generation might learn anew, if only they face it.

In his famous speech, “The Soldier’s Faith,” the Civil War veteran and Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., confidently announced in 1895: “It is our business to fight, the book of the army is a war-song, not a hospital-sketch.” Not so, argued Faust: Before singing a war song, we might first listen to a Union surgeon’s description of the fields at Antietam a week after the battle: “The dead were almost wholly unburied . . . [they] stretched along, in one straight line, ready for interment, at least a thousand blackened bloated corpses with blood and gas protruding from every orifice, and maggots holding high carnival over their heads.” Faust showed with careful realism how mass death in the Civil War forced Americans not only to cope, as she puts it in chapter headings, with “dying . . . killing . . . burying . . . naming . . . realizing . . . believing . . . doubting . . . accounting . . . numbering . . . and surviving,” but with ultimately finding meaning in it all. Drew Faust has fulfilled the historian’s highest calling in telling us difficult stories through masterful and innovative uses of evidence. In prose both clear and beautiful, she has brought some of our darker side into the light.