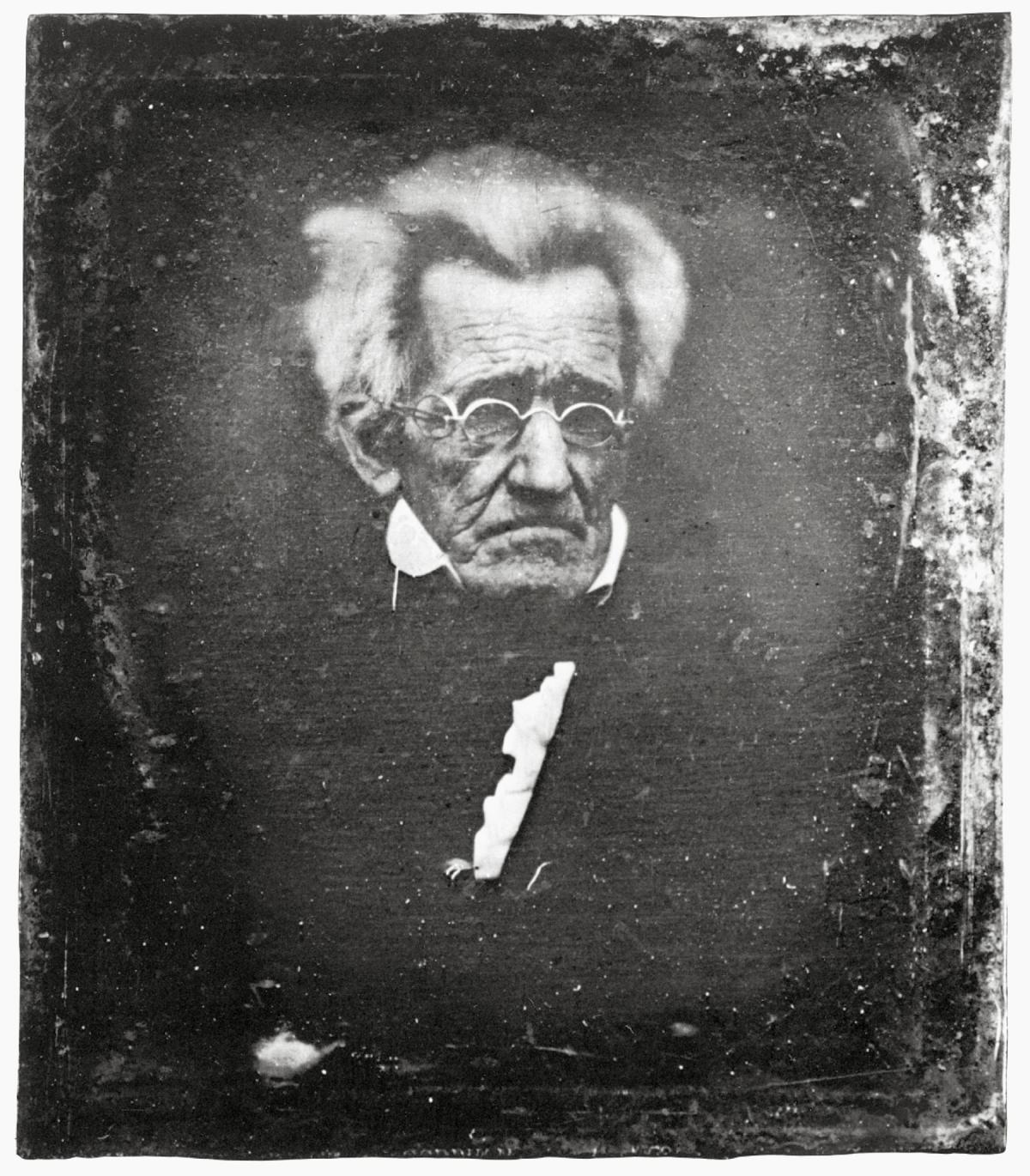

Though he no longer holds an exalted place in the American imagination, Andrew Jackson continues to draw attention. Witness Jon Meacham’s Pulitzer Prize-winning biography, American Lion, which chronicled the triumphs and travails of the seventh president’s two administrations. No less interesting, if slightly offbeat and irreverent, was the Broadway play Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson, which depicted Old Hickory as a mascara-wearing, “emo punk” rock star and included the tagline, “History just got all sexypants.”

Jackson’s image has undergone significant transformation since James Parton, a professional writer, penned his three-volume Life of Andrew Jackson on the eve of the Civil War. Parton created a dynamic portrait of the Hero of New Orleans that remains influential today. Rarely is a Jackson biographer able to resist quoting, in some way, Parton’s assessment of the Tennessee president:

Andrew Jackson, I am given to understand, was a patriot and a traitor. He was one of the greatest of generals, and wholly ignorant of the art of war. A writer brilliant, elegant, eloquent, without being able to compose a correct sentence, or spell words of four syllables. The first of statesmen, he never devised, he never framed a measure. He was the most candid of men, and was capable of the profoundest dissimulation. A most law-defying, law-obeying citizen. A stickler for discipline, he never hesitated to disobey his superior. A democratic autocrat. An urbane savage. An atrocious saint.

Parton based his interpretation of Jackson and his presidency, which he called “a mistake on the part of the people of the United States,” on several caches of private letters held by Jackson family members and close confidantes. Supplementing this voluminous correspondence were extensive personal interviews with men and women close to Jackson, compiled as the biographer traveled across the United States in the late 1850s. During a trip to Nashville in early 1859, he interviewed one of his most interesting subjects, an African-American woman named Hannah. She had been one of Jackson’s slaves and now belonged to Andrew Jackson Jr.

During Parton’s visit, Hannah gave him a tour of Jackson’s Nashville home, The Hermitage, which had fallen into disrepair. Parton recorded in his research notebook that Hannah thought highly of her former owner. He “was more a father to us than a master,” Parton recorded her saying, “and many’s the time we’ve wished him back again, to help us out of our troubles.” Hannah became “fired up” when she believed that Jackson was being spoken about “disrespectfully.”

“We black folks is bound to speak high for old Mawster,” she reportedly said. “He was good to us. You know what he was to you, and must speak accordin’. But we is bound to speak high for him.”

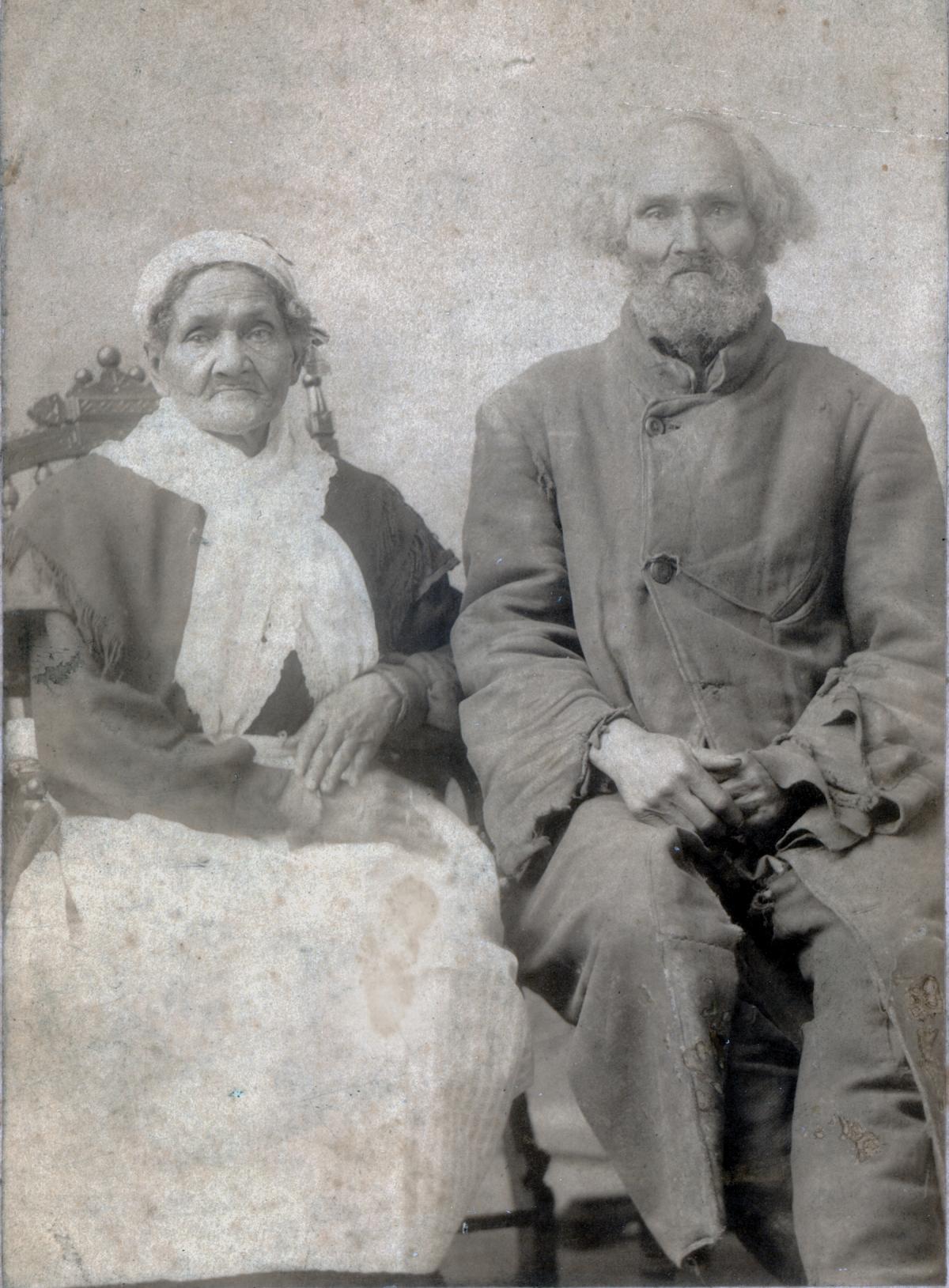

In addition to being a source for Parton’s biography, Hannah was the subject of two other interviews following the Civil War. In these newspaper interviews, one with the Cincinnati Commercial in 1880, the second with the Nashville Daily American in 1894, she covered a number of different subjects: Andrew Jackson’s treatment of her and other slaves, Andrew and Rachel Jackson’s deaths, and other anecdotes about life at The Hermitage.

Hannah recalled the special treatment that Jackson gave her from the very earliest days of her servitude, which began around 1808. She told one reporter that Jackson received her and her mother as payment for legal services rendered in east Tennessee. On the trip back to Nashville, Hannah remembered being carried “in his arms” and promised a ginger cake if she adjusted his stirrup. She also told the reporter that she “used often to be employed by Gen. Jackson to comb his hair,” with the promise of “some trifling present in payment for her services.” Because Hannah was “a favorite servant,” Jackson allowed Hannah’s wedding to Aaron to take place in The Hermitage’s dining hall. Hannah was also trusted enough to supervise The Hermitage household for Jackson while he was away in Washington for his second presidential term (1833–1837). Jackson never sold members of her family, Hannah pointed out. “He was mighty good to us all.”

One of the most dramatic accounts that Hannah discussed was Jackson’s final hours of life. She was present in his bedroom when he died on that Sunday afternoon in June 1845. According to her, some of Jackson’s last words were, “I hope to meet you all in Heaven, both black and white.” (Other witnesses in the room, including Jackson’s doctor, his niece, and his son all recorded those words or a close variation of that sentiment.) One of the newspaper reporters observed that

[o]n the subject of slavery, Aunt Hannah’s views are different from those of most of her race. Having had an indulgent master and mistress, she has always insisted that the years spent in slavery were the happiest of her life. To labor for those who were benefactors was no slavery to her.

He (presumably, the reporter was a man) underscored Hannah’s satisfaction with her lot in life by including her assessment as she looked ahead to her pending one-hundredth birthday: “Everybody is good to me, both white and colored, and I have no reason to complain.”

It was true that Jackson did not divide Hannah from her children, except to bequeath them among the members of his own family. And the records show that as late as March 1860, Hannah was busy with the upkeep of The Hermitage. But with the Civil War came a rupture that casts Hannah’s feelings in a rather different light.

In June 1863, Sarah Jackson reported that Hannah had “gone over to the Yankees,” having “been very insolent for some time.” Rachel Jackson Lawrence, Jackson’s granddaughter, announced that Hannah was “making 20 dollars a month” and blamed her abandonment of the Jacksons on “the Yankees.” Having emancipated herself, Hannah worked as a midwife and lived with family in Nashville until her death in 1895.

The two newspaper interviews she gave, along with the time spent with James Parton in 1859, constituted Hannah’s public reminiscences of her former owner and substantively shaped the memory of Old Hickory, particularly regarding his attitude toward, and treatment of, slaves. The Jackson of her memory was paternalistic, indulgent, and kind, and, while he did not practice racial equality, certainly seemed to believe that whites and blacks were spiritually equal in the eyes of God. But can Hannah’s assessment of Jackson and his relationship with his slaves be trusted?

Historians have mostly overlooked the slave experience at The Hermitage. It is possible, however, to outline generally what it was like to live there. Some slaves lived in yard cabins, as close as ninety feet away from the main house. One of those slaves, for example, was a man named Charles, who served as Jackson’s personal slave and carriage driver. Other slaves lived much farther away, in quarters close to the fields in which they worked. Like on many Southern plantations, these slaves would have labored at the plantation’s main focus: agricultural production, primarily cotton, but also corn, hemp, and tobacco. Additionally, slaves raised livestock and ran the cotton gin and grain mill on the property. One final responsibility was tending to Jackson’s stable of racehorses. Jackson had a longtime trainer, an enslaved man named Dinwiddie, who trained Old Hickory’s equestrian stock. As an elite Southern planter, Jackson recognized the importance of slave property to his financial security and, when he could, sought to increase the number of slaves he owned. Between 1812 and 1820, Jackson’s enslaved population increased from twenty to forty-four. By the time he was president, he owned nearly one hundred slaves; an estate inventory following Jackson’s death counted 161 slaves, split between The Hermitage and a Mississippi plantation.

Ignored in Hannah’s recollections was the violence visited upon The Hermitage slave community, such as when Jackson ordered runaway male slaves whipped upon capture. In 1804, for example, Jackson placed a newspaper advertisement describing a runaway slave named Tom Gid. He promised “ten dollars extra, for every hundred lashes any person will give him, to the amount of three hundred” if Tom were captured outside of the state. (Tom does not appear to have been captured.) In the case of one repeat offender named Gilbert, running away cost him his life. In August 1827, Jackson’s overseer, Ira Walton, determined to whip Gilbert in front of the other slaves to send a message; instead, the slave fought back and ended up dead from a knife wound.

Female slaves were not immune to violence either. In 1815, one of Jackson’s nephews informed him that “[y]our wenches as usual commenced open war” against the overseer. This familiar behavior stopped after the slave women were “brought to order by Hickory oil,” a reference to being whipped. In 1821, the Jacksons were living in Florida while Andrew served as territorial governor. During one of his absences, Rachel wrote to her husband that her slave, Betty, “has been putting on some airs, and been guilty of a great deal of impudence.” Her sin was washing clothes for individuals in the neighborhood without Rachel’s “express permission.” Jackson instructed several of the men who formed part of their Pensacola household to punish Betty with fifty lashes at “the public whipping post” if she refused to obey his wife. Betty was “capable of being a good & valluable servant,” he wrote one of the men, “but to have her so, she must be ruled with the cowhide.”

At the same time, the paternalistic Jackson that Hannah described also appeared to exist. When, in 1810, a neighbor, William Purnell, accused Dinwiddie of poisoning one of his horses, Jackson defended his horse trainer. He demanded that Purnell either provide detailed evidence implicating Dinwiddie or prepare to be punished himself. On another occasion, in 1838, relatives accused four of Jackson’s male slaves of causing a riot at a holiday party and murdering another slave. Jackson hired a legal team to defend his slaves, arguing “it was a constitutional right, that all men by law [are] presumed to be innocent until guilt was proven.”

One should not read too much into these paternalistic examples, however. While it is certainly possible to argue that they represented Jackson’s concern for his slaves, what was at stake in both of these instances was not only the slaves’ complicity in criminal activity but also Jackson’s honor as a Southern gentleman. The question of his slaves’ guilt or innocence reflected on his reputation: What kind of master could Jackson be if he was unable to keep his slaves from poisoning other people’s horses and starting riots? Jackson’s prickliness about his public face, which resulted in several duels and violent assaults, suggests that whatever sympathy he may have had for his accused slaves, what mattered most was protecting his honor.

One of Hannah’s memories hints at a possible internal struggle taking place within Jackson, that, if true, must have jeopardized his reputation. She recalled that a white officer “who used to stay for weeks at our house led one of the young colored girls off.” When Jackson found out, he “said nothing that I know of,” but when Rachel caught wind of the liaisons, she was “mad, mad, MAD [with rising inflection], and she was always mad about it.”

This anecdote is particularly intriguing in light of the suggestion by Hannah’s descendants that she and Jackson had, at the very least, a sexual, if not a romantic, relationship that produced children. In her “novel based on fact,” Unholiest Patrimony: “Great Is the Truth and It Must Prevail,” Dorothy Price-Haskins, one of Hannah’s descendants, argues that Jackson had a sexual relationship with her ancestor, resulting in the birth of their daughter, Charlotte. She claims that Charlotte documented this relationship in her journal, which, along with other evidence of Jackson’s paternity, has remained in family hands because of harassment and threats. If Price-Haskins is right about Andrew Jackson and Hannah, then Rachel Jackson may have been projecting her anger toward her husband onto the male houseguest suspected of fraternizing with the female slave.

Price-Haskins’s argument underscores how little attention historians have paid to Jackson’s slave ownership. The slaves of Thomas Jefferson, George Washington, even James K. Polk, have all been studied in greater depth than those of Jackson. Why have historians cared so little about Jackson’s relationship with his slaves, especially given the claim that he fathered a child with Hannah? One reason—as Jennifer James, a professor of English at George Washington University who is working on a book about Jackson’s legacy among African Americans, pointed out in conversation with me—is that there is no DNA evidence available to corroborate the oral tradition of the relationship, as was the case with Jefferson and Sally Hemings, the enslaved woman whom most historians agree bore children for the third president. At the same time, unlike Jefferson’s case, no allegations about Jackson’s involvement with Hannah (or slave women in general) made during his lifetime have surfaced. This lack of genetic and contemporaneous evidence makes it unlikely that a Jackson-Hannah relationship will ever grab the historical profession’s attention, much less that of the public.

Another factor at work is Hannah’s image as a non-threatening African-American woman. While photographic evidence demonstrates that she did not physically resemble the stereotypical “Mammy” character common in late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century American popular culture, the 1880 and 1894 interviewers describe Hannah as what one scholar has called an “Aunt Jemima” character.

Aunt Jemimas were, writes Donald Bogle in the book Black Beginnings, “blessed with religion . . . [able to] wedge themselves into the dominant white culture. Generally, they are sweet, jolly, and good-tempered.” Hannah’s two interviews are infused with religious references and indicate her knowledge of, and participation in, the private world of the Jacksons. Terrell even described Hannah as wearing “a ’kerchief turban-fashion,” a familiar accoutrement historically associated with “Aunt Jemima.”

A closer reading of Parton and the two newspaper interviews, however, reveals an African-American woman who may have proved desirable to someone such as Jackson. Parton described Hannah as looking younger than her approximately sixty years of age and “yellow,” implying a mixed racial heritage. Terrell, the 1880 interviewer, made a similar comparison when he called her “a cinnamon-colored mulatto.” The unnamed 1894 interviewer alluded to several characteristics that set Hannah apart from the familiar racist Jim Crow-era stereotypes. She possessed “unusual intelligence for a colored woman” who lacked a formal education and “a certain sprightliness of manner, comeliness of features, and much good, sound common sense.” Hannah’s “honesty and truthfulness have ever been unimpeachable, her unselfishness and benevolence worthy of imitation,” in his assessment.

Even if it were somehow provable that Jackson and Hannah were sexually involved, it seems likely that the relationship would simply become another black mark on Jackson’s legacy, as Professor James said to me. Unlike Washington or Jefferson, Jackson no longer resides in the American pantheon of great presidents. He was not the author of the Declaration of Independence or the “Father of Our Country.” Instead, like some of Jackson’s contemporaries, many Americans today seem to believe that he was a tyrant who disgraced the executive office with his uncouthness, destroyed the national bank (and, with it, the nation’s economy), and attempted to wipe out several Native American groups. With that kind of reputation, it perhaps does not seem that significant if he had a relationship or produced a child with a slave woman.

For decades, biographers knowingly or unknowingly relied on Hannah’s memory of Jackson to understand him as a slave owner. For example, in his 1860s biography, Parton referred to Jackson as “the most indulgent, patient, and generous of masters,” whose slaves “loved him, and revere his memory.” (The present tense of “revere” suggests that he may have had the descriptions that Hannah gave him during his 1859 visit specifically in mind while writing this assessment.) Marquis James’s Pulitzer Prize-wining Life of Andrew Jackson (1938) called Old Hickory the “ideal slave-owner” who shared a “genuine and reciprocal attachment” with his slaves. Even Robert V. Remini, who was widely regarded as the preeminent Jackson-era historian prior to his death in 2013, fell victim to perpetuating Hannah’s image. While he admitted that Jackson “could be exceedingly cruel, if not barbaric,” he also argued, without supporting evidence, that Jackson’s “abominable disposition toward recalcitrant slaves had softened” by the time of his second presidential term. Remini also suggested that the demise of Jackson’s slaves “genuinely disturbed him—and not on account of the financial loss.” Recently, biographers such as Hendrik Booraem, Andrew Burstein, and Jon Meacham have taken a more realistic view of Jackson that recognizes his desire to own slaves in order to maintain social status and remain wealthy.

For a number of decades, Hannah’s memory also influenced public perceptions of Jackson at his home in Nashville. When I worked as an interpreter at The Hermitage during the summer of 1995, an older docent overheard me giving a tour in which I referred to Jackson’s slaves. She pulled me aside and instructed me to call the slaves “servants,” because that is what “the General” would have called them. In recalling that conversation recently, I was struck by its irony: At the very same time that I was being told to ignore slavery’s reality at Jackson’s home, The Hermitage was the site of an extended archaeological project focusing on uncovering slaves’ lives. Reflecting on her role in that project, anthropologist Whitney Battle-Baptiste noted that the local African-American community had long viewed The Hermitage as “a segregated place,” in large part because of “the continued invisibility ascribed to the descendants of enslaved Africans at the museum.”

That invisibility no longer exists. In 2005, The Hermitage created an exhibit on the plantation’s enslaved people that continues to be displayed in the visitor center and may be expanded in the future. Guests cannot miss reading the biographies of several slaves, including Hannah, as they walk the hallway leading to the museum. In the several times that I have visited The Hermitage since 2008, it is clear from listening to the audio recordings that guests can use on the tour, and from interacting with the docents, that serious attention is being given to help the public understand the centrality of slave labor to the home and lifestyle that they are encountering. Hannah, then, is still influencing the ways in which Americans think about Jackson, but in a very different way than before.

*On April 13, 2015, this article was updated to credit Jennifer James’s contributions to the author’s thinking about why historians have not been more interested in reports that Hannah had a sexual relationship with Jackson, and to credit Donald Bogle as the source of a quotation that, because of an editorial error, had been omitted from the published version.