As an evangelical kid growing up in the late 1970s and early ’80s, one of my favorite church youth group songs was “I Wish We’d All Been Ready.” Originally recorded in 1969 by Christian rock patriarch Larry Norman, the song conjures a world after the rapture, when many believe God will scoop the saved up to heaven and leave the rest behind. It is a world empty of God and full of tribulation. “Life was filled with guns and war,” the song begins, “and everyone got trampled on the floor. I wish we’d all been ready.” Children are dying, the sun grows dark and cold. Food is so scarce that “a piece of bread could buy a bag of gold.” A grim scene. But what was most horrifying about this doomsday scenario was that it was a world after God. “There’s no time to change your mind,” the chorus laments, “the Son has come, and you’ve been left behind.”

Our youth group must have sung it more than a hundred times. No one made eye contact. We all looked at the floor, feeling the weight of the words, as if we were the ones Christ had left behind when he returned to rapture his followers up to heaven. The song invited us to imagine a time when it was already too late, when our ambivalence, our lack of faith, had left us each alone, without God and, perhaps more terrifying at that age, without friends.

I had no idea that Larry Norman was the song’s original writer and performer. I had never heard of him. I assumed the original version was the one performed by the Fishmarket Combo during the opening credits of the 1972 evangelical rapture horror movie A Thief in the Night, which we watched every year or so.

Then again, like most youth group kids in America, I was largely oblivious to everything going on in the larger world of evangelical Christianity. Between the rise of the Christian youth movement and a growing fascination with the darker traditions of Christianity rooted in the Book of Revelation, we were witnessing the dawn of a new era of evangelical apocalyptic horror culture, one that makes you wonder what might come next.

The Rise of Evangelical Pop Culture

The late 1960s and early ’70s were transformative years for American evangelicalism generally and evangelical youth culture specifically. Emerging in the 1940s out of and in some ways against the fundamentalist movement, which had become increasingly countercultural and sectarian in the wake of the Scopes trial, “neo-evangelicalism,” as it was then called, made American youth culture its mission field. It sought to make its gospel message popular by mainstream cultural standards. In the perennial Protestant Christian dilemma of preservation versus popularization—protecting and preserving the sanctity of the tradition versus getting the Word out broadly—evangelicals leaned toward popularization, taking as their motto Paul’s declaration “I have become all things to all people, so that I might by any means save some” (1 Corinthians 9:22).

Central to their approach were para-church organizations such as Youth for Christ, Campus Crusade for Christ, and Young Life, which aimed to attract popular kids with the expectation that others would follow. Their weekly club meetings included games and skits along with more serious Bible study and prayer. Begun as a series of Saturday-night youth rallies, Youth for Christ had attracted hundreds of thousands of young people in big cities across the United States. Rallies were led by young, energetic preachers such as Billy Graham (the first full-time employee of Youth for Christ) and were modeled on television shows that were popular at the time. Organizers produced slick ads and created mainstream radio and television tie-ins. Some evangelists went so far as to adopt the voices and styles of celebrities such as Frank Sinatra. Others, such as Graham, soon found their own distinctive star power.

By the early 1970s, however, neo-evangelical rallies were looking less like a Frank Sinatra show and more like a Led Zeppelin concert. In 1972, Campus Crusade for Christ hosted Explo ’72, a weeklong gathering of high-school and college students in Dallas, Texas. The event culminated in what was later dubbed the Christian Woodstock, an eight-hour-long Christian rock concert in the Cotton Bowl that drew more than 100,000 people and featured none other than Larry Norman and his hit rapture song, “I Wish We’d All Been Ready.”

Rapture Theory

I grew up assuming the expectation voiced in Norman’s song—that believers will be raptured into heaven and unbelievers will be left behind as all hell breaks loose on earth—was a cornerstone of Christianity and had been so since Jesus’s time. In fact, rapture theory is a rather recent development in the history of Christian thought. Originating in the early nineteenth century with the work of the dispensationalist theologian John Nelson Darby, it quickly gained popularity among end-times-oriented Christians, thanks especially to its incorporation into the notes and illustrations of study Bibles such as the Scofield Reference Bible (1909) and its centrality in popular rapture books such as Hal Lindsey’s 1970 best-seller The Late Great Planet Earth.

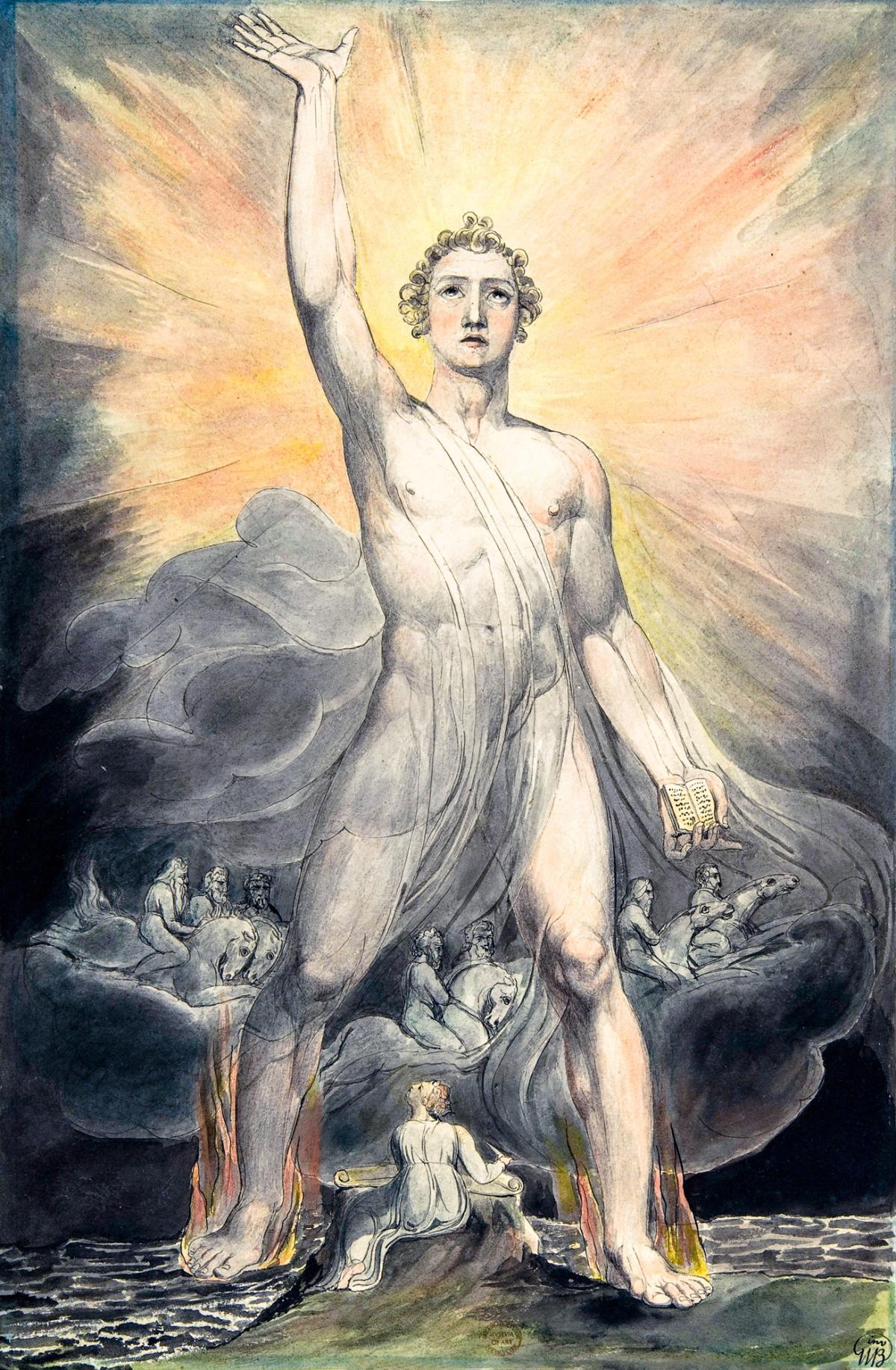

These and other proponents of rapture theory often draw on apocalyptic texts from the Christian scriptures, including the prophet Daniel and, above all, Revelation. The Apocalypse of John, or Revelation, comprises a series of dramatic doomsday visions that an otherwise unknown John (unrelated to the Gospel of John or the epistles of John) says God revealed to him during his stay on Patmos, a small island off the west coast of Asia Minor (modern-day Turkey). Probably writing sometime between the beginning of the Jewish wars with Rome, which culminated in the destruction of the Jerusalem temple in 70 CE, and the end of the first century CE, John addresses his text to seven churches located on the nearby mainland. He exhorts them to persevere in their faithful obedience, describing wildly violent tribulations and a divine judgment that is soon to come, all of which will end in the annihilation of the present world. In its place, God will create a new heaven, a new earth, and a new Jerusalem, where he and Christ will reign with their angels and saints forever.

The text does not present a vision or prediction of the end of the world. Instead, it unveils the edge of the world. It is an overwhelmingly violent, cosmopolitical end that is, in the same moment, an extravagant new beginning in which death and suffering will be no more. And all of it—all this shock and awe—is brought on as much by God, Christ, and his angels as by God’s monstrously diabolical enemies, the Satanic red dragon and his beasts. Dreadful and hopeful, dreamy and disgusting, Revelation is a sticky bit of biblical tradition: hard to grasp firmly and even harder to let go. Indeed, it is precisely the book’s mind-boggling incomprehensibility that has proven to be so generative for so many interpreters, and so aggravating for so many others, over the centuries.

In fact, for as long as people have been reading this apocalyptic text, they have been arguing about its status as scripture. In the third century, Bishop Dionysius of Alexandria reported that many Christians rejected it, “pronouncing it without sense and without reason . . . , covered with such a dense and thick veil of ignorance.” In his Ecclesiastical History (325 CE), Bishop Eusebius of Caesarea placed it in two mutually incompatible categories: as “undisputed” for some (that is, unquestionably belonging in the canon of Christian scriptures) and as “disputed” for others. And although Athanasius, Bishop of Alexandria, included it in his canonical list of New Testament scriptures in 367 CE, his contemporary, Cyril of Jerusalem, excluded it from his. More than a millennium later, during the Reformation, the book of Revelation’s status was still in question. In his 1522 edition of the New Testament, for example, Martin Luther wrote that he saw no evidence of its inspiration, that no one knows what it means, and that “there are many far better books for us to keep.” (Ironically, Lucas Cranach the Elder’s wildly creative woodcut illustrations of Revelation made it one of the most popular books in Luther’s Bible.) Such disputes over the social and theological value of Revelation have chased it through history and continue to this day.

Given Revelation’s influence on apocalyptic thought and rapture theory, one would expect it to include a vision of the rapture itself, or at least references to it. Not so. There is no rapture in the Book of Revelation. Rather, rapture theory is stitched together from a few biblical fragments gathered from disparate sources. Three texts in particular: the promise in Revelation’s letter from Christ to the church in Philadelphia that “because you have kept my word of patient endurance, I will keep you from the hour of trial that is coming on the whole world to test the inhabitants of the earth” (Revelation 3:10); the assurance in Paul’s letter to the Thessalonians that after God raises from the dead those believers who have already passed, “then we who are alive, who are left, will be caught up in the clouds together with them to meet the Lord in the air, and so we will be with the Lord forever” (1 Thessalonians 4:17); and Paul’s declaration to the church at Corinth that “we will all be changed, in a moment, in the twinkling of an eye, at the last trumpet; for the trumpet will sound, and the dead will be raised imperishable, and we will be changed” (1 Corinthians 15:51–52).

From these fragments, rapture theory builds an idea that the saved, dead and alive, will be raptured up from the earth to heaven. Then it plugs that idea back into Revelation as an event that will take place just before the reign of Satan and his beasts, thus saving Christ’s followers from the worst of the end-time tribulations. Those who are “left behind,” on the other hand, will be forced to worship the beast and take its mark (666) or be persecuted and killed.

Cinematic Raptures

These apocalyptic themes emerged in a robust Christian film industry in the 1940s, which produced, promoted, and distributed evangelical features in the familiar styles of Hollywood and B movies to show in local churches, libraries, school gyms, and community theaters.

One of the more successful of these companies was Charles O. Baptista’s Scriptures Visualized Institute. Not only did Baptista’s company produce dozens of evangelistic films for wide distribution; it also sold its own movie projector, called the Miracle Projector, which had a label guaranteeing that it would be “good until the return of the Lord Jesus Christ.”

In 1941, Baptista produced the very first evangelical rapture movie, called The Rapture. In documentary war-reel style, and no doubt haunted by the thousands of soldiers disappearing every day, this twelve-minute, sixteen-millimeter film includes many shots, cuts, and special effects that would become standard fare for rapture movies to follow: trains without conductors and other unmanned vehicles crashing into each other, empty cradles, and people disappearing while perplexed others are left behind, all interspersed with antiphonal text in the sky, asking, “Are you ready?” The Rapture was a big hit, shown in churches and at youth rallies across the United States for years.

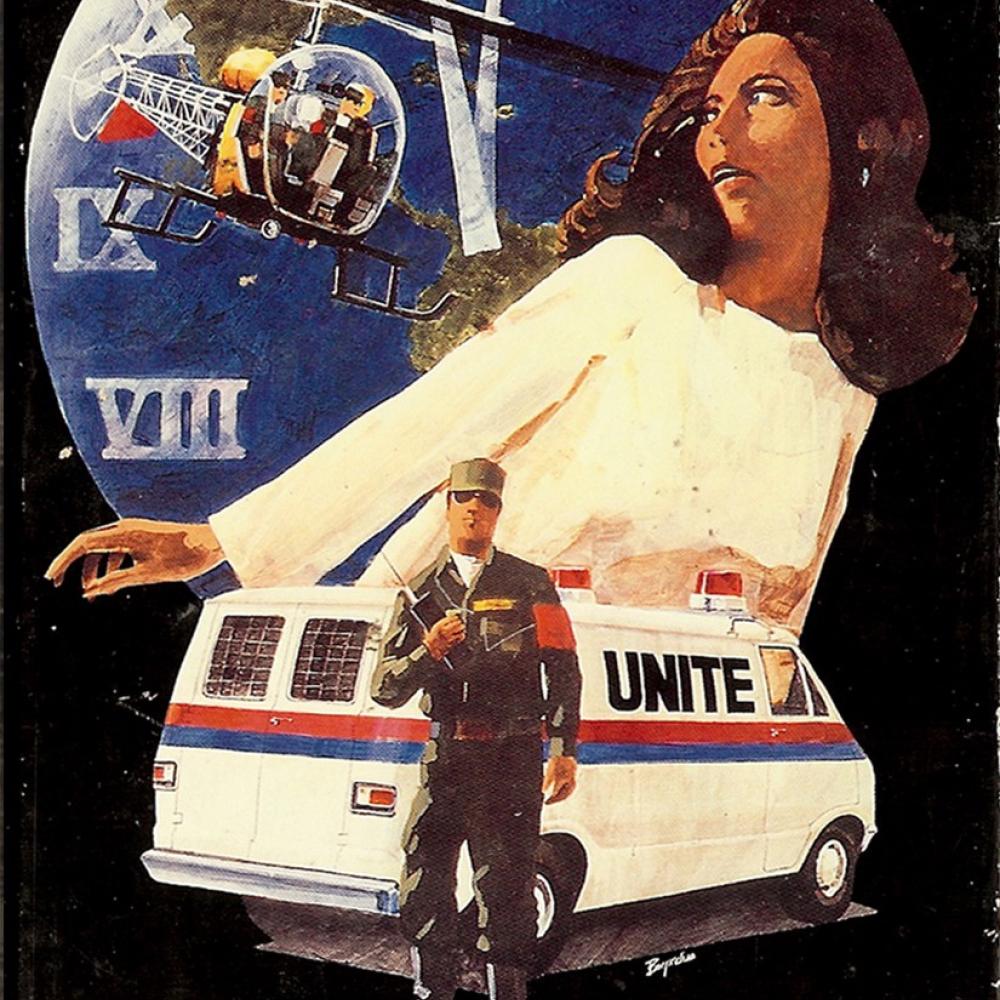

But no rapture movie has been more widely watched and influential on American culture or on the emergence of evangelical horror culture than the 1972 movie A Thief in the Night. The film follows a young woman, Patty, who awakes one morning to find the rapture has happened, taking her recently converted newlywed husband and leaving her behind. This new world is abandoned by God and dominated by the powers of evil, represented by a one-world government called UNITE, which stands for “United Nations Imperium of Total Emergency.”

The production company, Mark IV Pictures (a reference to Mark 4:33, “With many such parables he spoke the word to them, as they were able to hear it”), was a collaboration of Russell S. Doughten Jr., a longtime Christian, and Donald W. Thompson, a new convert to the faith. Both had extensive experience producing and directing secular films, including B-movie horror and action features. Their ambition was to make Christian action-adventure movies for young people.

A Thief in the Night was shot entirely in Des Moines, Iowa, where Doughten and Thompson lived, on a budget of about $60,000, and it was promoted only by word of mouth. Its success exceeded their wildest expectations. At the peak of its popularity, Mark IV was booking 1,500 rentals per month. Some local libraries held as many as fifteen copies in order to keep up with the demand from churches and other organizations. Many groups, including my own youth group, rented it regularly—for annual Halloween or New Year’s Eve showings.

In all, Thief generated more than $1 million, an unprecedented amount in rental revenues. By 1984, including videotape sales, it had reportedly grossed $4.2 million. Estimates as to how many people have seen the film range from one hundred million to an astounding three hundred million viewers.

Given those numbers, it is not surprising that the movie had a tremendous influence on American teens. It literally scared the hell out of many, who started getting themselves ready by converting at the end of the movie. In fact, Doughten and Thompson had this effect in mind: in one scene, a little girl who is terrified of being left behind without her mom says a very simple, scripted prayer to ask Jesus into her heart, thereby providing viewers with the words they needed for their own conversion prayers. Still, other traumatized youth ran the other way. Rock performance artist Marilyn Manson, for example, recalls being terrified by the movie, which ultimately helped push him in a more Nietzschean beyond-good-and-evil direction.

Thief also had a marked influence on the emergence of evangelical horror—a genre of film aimed at scaring people into conversion. Not only did its financial success pave the way for Mark IV’s sequels (A Distant Thunder in 1978, Image of the Beast in 1981, and The Prodigal Planet in 1983), it opened the door to other kinds of Christian B-movie horror, most notably the hellfire-and-real-maggots splatter films by Ron and June Ormond, who converted to Christianity after cutting their teeth making sexploitation movies in the sixties. Some of their best-known movies, such as The Burning Hell (1974) and The Grim Reaper (1976), sent overwhelmed viewers running from church basement screenings to throw up, cry, and get saved.

Encrypting Revelation

The movie includes elements from Revelation without explicitly referencing the text. The first and most obvious is the use of the computer-generated number 666 as the mark people must take to show their submission to and alliance with UNITE. Oddly, the number is never identified as the mark of the beast of Revelation, which his minions must bear on their right hand or forehead in order to buy or sell goods (Revelation 13:16–18). Nor is UNITE ever associated with the beast or its demonic dominion over the godforsaken earth. These undeciphered symbols leave Patty, and most of the viewers identifying with her, inexplicably uncertain and in the dark.

Another idea from Revelation derives from the book’s image of armored locusts with human faces that are released to torture those who do not have the seal of God on their foreheads (Revelation 9:1–11). In an early scene, a shot from below of a helicopter taking off fades into a close-up shot of a grasshopper on a kitchen window. Perplexing to many viewers, this visual association of helicopter and grasshopper is a reference to the belief, popular among end-times enthusiasts in the early 1970s, that the locusts John from the Book of Revelation thought he saw were actually Cobra attack helicopters that would be part of the future battle of Armageddon. Later in the movie, Patty is chased by UNITE soldiers flying the same helicopter.

Revelation is also woven into the film in the warning that Christ will return “like a thief in the night” (Revelation 3:3 and 16:15; see also 1 Thessalonians 5:2). Having become so commonplace in evangelical discourse, this idea is usually taken simply to mean that it will happen when you least expect it. But placed in the context of this movie, a more horrifying sense emerges, namely, an image of the divine as a threatening figure who could, at any moment, invade your home and steal you or, worse, your loved ones—which is exactly what happens to Patty, as she awakens to find her husband’s electric shaver buzzing in the sink.

From Rapture Horror to Rapture Adventure

Others have traced the lucrative path from Thief through the many rapture and tribulation movies and video shorts of the 1980s and ’90s that led to Cloud Ten Pictures’s Left Behind movies, all based more or less on the best-selling series of apocalyptic fantasy-action novels by Tim LaHaye and Jerry B. Jenkins: first, the Left Behind film trilogy (Left Behind: The Movie in 2000; Left Behind II: Tribulation Force in 2002; and Left Behind III: World at War in 2005) and then the single Left Behind movie starring Nicolas Cage in 2014.

As the title suggests, and as authors LaHaye and Jenkins readily acknowledge, the Left Behind series drew much inspiration from A Thief in the Night and its sequels. Indeed, the Left Behind movies and books are chock-full of now-stock motifs from the evangelical apocalyptic imaginary drawn from early dispensationalist diagrams, Baptista’s early rapture film, and, of course, A Thief in the Night. There are the weeping mothers, clutching baby blankets and teddy bears of raptured children; wifeless husbands and husbandless wives; pets lingering over the clothes of raptured masters (apparently babies and young children go but pets do not); and, of course, remorseful wayward pastors left behind in their chapels, realizing that they betrayed their faith only when it was too late.

And yet, although cinematographically unremarkable, the Left Behind trilogy and the most recent Left Behind redux with Nicolas Cage are worth our attention as results of the changing face of evangelical apocalyptic culture. They signal a shift away from horror and toward thrill. In them, apocalyptic dread has become apocalyptic anticipation.

In A Thief in the Night, being left behind really was a living nightmare, abandoned in a creepily dull, God-forsaken Iowa wasteland. There the withdrawal of God highlights the absence of loved ones, and the withdrawal of loved ones highlights the absence of God. In the Left Behind movies, on the other hand, as in the novels and video game, the postrapture world is where all the action is. Here we have an apocalyptic thriller, as our heroes, the “tribulation saints,” lead the ultimate resistance movement against the ultimate bad guy: the Antichrist, Nicolae Carpathia, whose name and Bela Lugosi-like accent suggest a sort of evil descendent of Bram Stoker’s original invader from the Carpathian Mountains. In these movies, unlike in Thief, we almost feel bad for the ones who got raptured. They are missing out on all the excitement.

And yet, whether horror or adventure, what these different evangelical rapture stories have in common is something we see again and again throughout the popular culture of Revelation: a widespread fascination with apocalyptic violence and diabolical evil that trumps the beauty of its final vision of a new heaven and new earth.

Why does the excessive brutality and bloodshed in the middle of the book so overshadow the joy and peace of its final vision of the resurrection of the dead, the coming of a new heaven, a new earth and a New Jerusalem, and the healing of all nations? In the end, is such a happy ending simply inconceivable? Is the extreme gladness and well-being of the final vision harder to believe than the extreme violence and horror that comes before it? Could it be that, despite its overwhelming, even unimaginable atrocities, many of us find a world filled with such horrors more believable than a world without them?