Orson Welles was sorry. No, really. He was.

On October 31, 1938—as children across the country were preparing for an evening of trick-or-treating—Welles appeared at a press conference to explain a stunt of his own. The night before, the Mercury Theatre on the Air—CBS Radio’s incarnation of the fabled theatrical troupe Welles ran with producer John Houseman—had offered its fresh interpretation of H. G. Wells’s 1898 novel The War of the Worlds.

For much of its duration, the program was presented as a faux newscast. Consequently, Welles, who was then all of twenty-three, had somehow persuaded a portion of the public that Martians were annihilating Earthlings. The New York Times headline painted the picture: “Radio Listeners in Panic, Taking War Drama as Fact.”

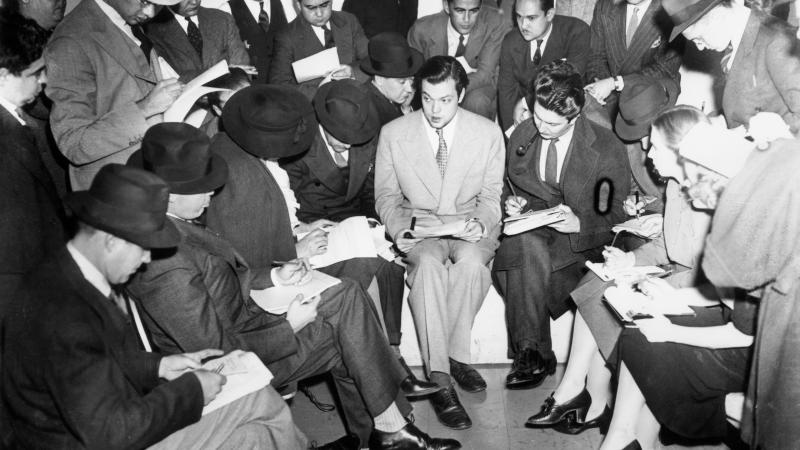

So, seated among a semicircle of eagerly scribbling reporters, Welles wore an oh-so-serious expression and spoke in sincere, thoughtful tones. “I know that almost everybody in radio would do almost anything to avert the kind of thing that has happened, myself included,” Welles said. “Radio is new, and we are learning about the effect it has on people. We learned a terrible lesson.”

John Landis, for one, isn’t buying it.

Landis is best known as the accomplished director of The Blues Brothers (1980) and An American Werewolf in London (1981), but he also knew Welles. In the 1980s, Landis was set to coproduce Welles’s unmade The Cradle Will Rock, which recounted the behind-the-scenes story of one of his most memorable productions at the Mercury Theatre. Landis says that he is unpersuaded by the performance Welles gave the day after The War of the Worlds.

“He was a brilliant and innovative man, and he milked it for all it was worth,” Landis says. “When they talked about that he was embarrassed by it, I don’t think so. . . . If you look at that press conference, he’s so contrite, and he’s just acting his brains out, and he’s so clearly delighted.”

It’s easy to imagine why Welles might have been tickled pink at the public’s purported panic over The War of the Worlds, which celebrates its eightieth anniversary this month. While retaining the basics of Wells’s original tale, Welles and scenarist Howard Koch tinkered with its setting: What had been 1890s-era England became 1930s-era New Jersey. Even more devilish—and, frankly, potentially confounding to the public—was the choice not to dramatize the story but to dish out its details newscast-style. In a cast full of talented voices, Frank Readick played a reporter from the made-up Intercontinental Radio News and Welles was a university professor attempting to reckon with the news of the interstellar invaders.

“We made a special effort to make our show as realistic as possible,” Welles said in an episode of the 1955 BBC television series Orson Welles’ Sketch Book. “That is, we reproduced all the radio effects, not only sound effects. Well, we did on the show exactly what would have happened if the world had been invaded. We had a little music playing and then an announcer coming on and saying, ‘Excuse me, we interrupt this program to bring you an announcement from Jersey City. . . .’”

In fact, Welles was accustomed to courting a kind of danger in his productions. About a year before The War of the Worlds, the Mercury Theatre had put on Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, which was marred when Welles, seeking a particular lighting effect, demanded the use of a real dagger, rather than a fake, when he, as Brutus, stabbed Caesar (played by Joseph Holland). During one performance, Welles managed to wound Holland, an incident recounted by Mercury actor Norman Lloyd in my book Orson Welles Remembered. “These things happened with Orson,” Lloyd told me. “I never checked again, or even thought about checking, whether Orson kept using a real dagger. But I know that was the end of the dagger with Joe Holland!”

The record is unclear, however, as to whether Welles intended, or even contemplated, the ruckus he caused with The War of the Worlds. In a conversation with Peter Bogdanovich in the Q&A book This Is Orson Welles, Welles claimed to have foreseen the panic but not its scale. “Six minutes after we’d gone on the air, the switchboards in radio stations right across the country were lighting up like Christmas trees,” Welles said. “Houses were emptying, churches were filling up; from Nashville to Minneapolis there was wailing in the street and the rending of garments.”

Yet Marymount University professor Marguerite Rippy doubts that Welles could have fully anticipated such a response. “People try to act like he has more artistic intentionality than perhaps he does,” says Rippy, who wrote about The War of the Worlds in her 2009 book Orson Welles and the Unfinished RKO Projects. “To me, he is a man who really loves the fun of putting together the work, and I think he saw something that could be a really fun, effective show.”

Indeed, The War of the Worlds starts off unmistakably as a show—not a newscast, or anything like a newscast. The program is introduced as part of the Mercury Theatre on the Air, and the series’ signature music, an emphatic, pounding selection from Tchaikovsky’s “Piano Concerto No. 1,” is cued up. Welles then launches into lines closely adapted from the novel: “We know now that in the early years of the twentieth century, this world was being watched closely by intelligences greater than man’s yet as mortal as his own . . .” And, just to be certain that listeners grasp that what follows is fictitious, Welles speaks as though he is a voice from the future, saying that the invasion occurred in 1939—the following year! “On this particular evening, October 30,” Welles says, “the Crosley service estimated that 32 million people were listening in on radio.”

Welles’s tactful introduction of The War of the Worlds lends credence to an oft-repeated theory that helps account for the panic: Perhaps some listeners were late to the party. After all, who among us always catches the opening credits of our favorite radio or television show? “I think that the famous panic, one, is greatly exaggerated,” Landis says, “but, two, the people who did freak out from it were people who came into the program late.”

Yet to listen to The War of the Worlds again is to be reminded that those latecomers had every reason to freak out. In Welles’s most inspired touch, the program commences with an innocuous performance of dance music—“From the Meridian Room in the Park Plaza Hotel in New York City,” says an announcer played by William Alland, “we bring you the music of Ramon Raquello and His Orchestra.” Before we can say “cha-cha-cha,” however, bulletins begin to fly: Explosions have been discerned on the surface of the Red Planet, and a meteorite—or, well, we think it’s a meteorite—has turned up in Grover’s Mill, New Jersey. Yet Welles does not dwell too long on any single report—not at first, anyway. Agonizingly, he keeps resuming the dance music.

“That creates the sense of elongated time,” Rippy says. “It really doesn’t take you away from the narrative for very long, but because he keeps returning to an interruption, it makes you feel like more time has passed than has actually passed.”

Welles demonstrated a keen appreciation for the way news unfolds in real time. Remember, no reporter on the ground, or announcer in a studio, would have a sense of the big picture at first. Yet listeners are given enough scary bits and pieces to almost accept the “grave announcement” when it is finally spelled out: “Incredible as it may seem, both the observations of science and the evidence of our eyes lead to the inescapable assumption that those strange beings who landed in the Jersey farmlands tonight are the vanguard of an invading army from the planet Mars. . . .”

Each year around Halloween, Rippy plays a recording of The War of the Worlds for a class of freshmen students at Marymount. Many approach it skeptically at first, but when they settle in, Rippy says their reactions are genuine. “If you play it in a darkened auditorium and tell them not to talk, . . . it takes them about five to seven minutes and then they start getting a little nervous,” she says. “By the time you get to the point where people are really getting irradiated by the laser beams and screaming and dying, they really get visibly nervous.”

At the close, Welles offers an assurance in his own voice—“out of character,” he says—that the preceding program was nothing more than a mere “holiday offering” from the Mercury Theatre on the Air. Ironically, having just pulled the wool over some listeners’ ears, he wraps up with a sermon warning against the sin of gullibility. “That grinning, glowing globular invader of your living room is an inhabitant of the pumpkin patch,” Welles says before signing off, “and if your doorbell rings and nobody’s there, that was no Martian. It is Halloween.”

Here, Rippy says, Welles was having his cake and eating it, too—in effect, he was playing his own game of trick and treat. “It was the trick of giving the listeners this sort of narrative dupe,” she says. “And then the treat is an awareness—a self-awareness—of how easily manipulated you are.”

Whether or not the program is—or was— ever truly believed, The War of the Worlds endures for the way it engages an audience. “The whole basis of most art—certainly literature and the movies, and painting and sculpture and theater and ballet and opera, in fact, almost all of it—is what’s called suspension of disbelief,” Landis says. “You want [the audience] to accept, no matter how outrageous what’s going on.”

During their lunches together, Landis said, Welles would fluctuate between what he describes as two extremes—“arrogant and grandiose, and meek and humble.” The one time Landis brought up The War of the Worlds, Welles shifted to the latter mode. “He sort of belittled it,” Landis says. “He said, ‘Oh, that’s overblown.’ And I think he said, ‘It’s a good story.’”

For his part, Landis agrees with the master.

“It was very overblown, but it was good stuff with great publicity,” he says. “It was what’s called ‘a good story.’”