I can no longer count how many times I have read The Souls of Black Folk. A copy of the classic 1903 text by W.E.B. DuBois sits prominently on my bookshelf. The cover is worn; the pages are heavily underlined; every margin is scrawled with notes.

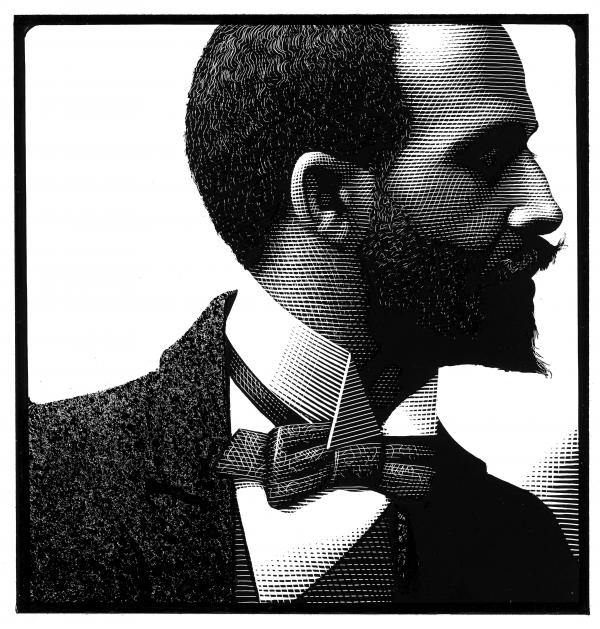

One of the greatest intellectuals this country has produced, DuBois dedicated his life to understanding the meaning of race, combating white supremacy and demonstrating the full humanity of Black people. He was astonishingly prolific, authoring 22 books in a variety of genres, with The Souls of Black Folk unquestionably his most famous.

In 2020, I imagine, I was not alone in turning to DuBois for guidance and clarity. A year when close to two million people around the world lost their lives to a terrible virus, 2020 will also be remembered as a time when Americans wrestled with the stability and very meaning of democracy. Along with a contentious election that tested the legitimacy of our institutions, we also experienced a dramatic reckoning with the country’s racist history and present. In great numbers, people read and thought and marched to declare that Black lives matter and demand that American democracy live up to its promise.

“The problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color-line,” DuBois wrote in Souls, and it remains true in the twenty-first century.

But another book by DuBois stands out right now as even more prescient and more attuned to America’s crisis of race and democracy. That book is Darkwater: Voices from Within the Veil, published one hundred years ago.

Revisiting the book today, one comes away with an enhanced perspective on the nation’s dark past and inspiration for how we can confront the uncertain days ahead. Envisioned as a sequel to Souls, Darkwater is a similarly experimental text, combining poetry, short story fiction, memoir, and previously published essays. Yet it differs in significant ways due to the context in which it was written: the traumatic years of the First World War and its aftermath. In ten chapters and accompanying interludes, DuBois explores the condition of being Black in relation to colonialism and empire, class and economic inequality, women’s rights and universal suffrage, labor and education, and other issues that reflected how much the world, and Black folk along with it, had changed since 1903.

Darkwater is steeped in rage. It exhibits DuBois at his most bitter about the catastrophic costs of white supremacy and the meaning of democracy for Black people. For DuBois, democracy was about more than just governments, elections, and individual political figures. It was an ethos, an ideal, and a goal to constantly strive toward. “Democracy is a method of realizing the broadest measure of justice to all human beings,” he wrote in Darkwater. America, then and now, has struggled to meet this standard. For this reason, Darkwater, even more so than The Souls of Black Folk, is the book of our times. One hundred years later, we are again grappling with the failures of democracy, the specter of Black death, and the tension between hope and despair. In Darkwater, DuBois reminds us that these challenges are not new.

The years of the First World War and its aftermath was one of the most traumatic periods of DuBois’s life. When the United States entered the war in April 1917, he reasoned that a successful battle to make the world “safe for democracy,” as championed by President Woodrow Wilson, would lead to the expansion of democracy for Black folk.

DuBois encouraged African Americans to enlist in the military, support the war effort, and, as he wrote in a controversial July 1918 editorial, “forget our special grievances and close our ranks shoulder to shoulder with our own white fellow citizens and the allied nations that are fighting for democracy.” He endured a firestorm of criticism, with his harshest critics accusing him of abandoning the fight for civil rights and betraying the race.

Following the November 1918 armistice, DuBois felt the urgent need to take stock of the war’s deadly costs and reassert his credibility. He traveled to France as part of the press delegation accompanying President Wilson to the peace conference. While overseas, he organized a landmark pan-African congress in Paris to advocate for the rights of African peoples. Although ignored by the world leaders gathering at Versailles, the pan-African congress signaled a new phase in the global movement for Black freedom and democracy.

DuBois also visited the battlefields and spoke directly with Black soldiers and officers about their struggle with racism in the American army. What he heard was heartbreaking. The American high command made sure that Jim Crow and the rules of white supremacy remained fully intact in France. Black labor troops toiled on the docks and in the trenches, under horrendous conditions, from sunup to sundown. Top white Army officials branded Black combatant soldiers as cowards and Black officers as incompetent. One after another, often through tears, they confided in DuBois and asked him to tell their story. He returned to the United States disillusioned and enraged.

DuBois was not alone in his frustration and anger. A chorus of young radical leaders, such as A. Philip Randolph, Hubert Harrison, and, above all else, Marcus Garvey, gave voice to the frustrations of Black people who had sacrificed for democracy during the war only to receive nothing in return. Their militancy threatened to eclipse DuBois as a spokesman for the race.

A “new Negro” had arrived, one who, inspired by the war, had no desire to compromise or turn the other cheek. “The new Negro is no coward,” Marcus Garvey declared in a June 1919 letter to his supporters. “He is a man, and if he can die in France or Flanders for white men, he can die anywhere else, even behind prison bars, fighting for the cause of the race that needs assistance.”

The specter of a “new Negro,” combined with the return of Black veterans, terrified many white Americans who feared changes to the racial status quo. As a result, in 1919, violence exploded throughout the country, in major northern cities and southern rural counties alike.

For three days beginning on July 19, white and Black residents in Washington, D.C., battled in the streets as Woodrow Wilson sat passively in the White House. Just over a week later, a race war exploded in Chicago that ultimately left 38 people dead. In Elaine, Arkansas, white mobs aided by U.S. troops slaughtered upward of two hundred Black people in one of the worst racial massacres in American history. The number of lynchings also skyrocketed, with at least 13 Black veterans killed, some still in uniform. James Weldon Johnson described these bloody months as the “Red Summer.”

Reflecting on the horror of the war, its bloody aftermath, and his own sense of responsibility as a leader of the race, DuBois poured his heart, mind, and soul into Darkwater. Throughout the summer and fall of 1919, he revised the manuscript to reflect the zeitgeist of the moment, crafting a book that exhibited the full range of his intellectual, political, and artistic genius. The book was published in February 1920 by Harcourt, Brace and Howe.

In Darkwater, DuBois set out, as he had in The Souls of Black Folk, to reveal the significance of race in America. With the opening autobiographical chapter, “The Shadow of Years,” he chronicled how half a century of his life and work had been defined by the color line. Even with opportunity and personal success, the “great, red monster of cruel oppression” always loomed. He saw himself as a soldier in the battle against race hatred, using his prodigious gifts to articulate the deepest feelings of Black people.

Darkwater demonstrates DuBois’s ability to understand the inner thoughts of white people as well. The book is a seminal contribution to the study of white racial identity that scholars in the late twentieth century would formally popularize. “But what on earth is whiteness that one should so desire it?” DuBois rhetorically asked in the blistering chapter “The Souls of White Folk.” The savagery of the world war, roughly 37 million people dead and wounded, combined with the grotesque nature of combat—machine guns, artillery, poison gas—had exposed not just the destructive potential of modernity but also the fallacy of European civilization and the delusion of white supremacy.

In scorching prose, DuBois wrote, “This is not Europe gone mad; this is not aberration nor insanity; this is Europe; this seeming Terrible is the real soul of white culture—back of all culture,—stripped and visible today.” While the origins of the war lay in the imperial rivalries of various European nations for control of the world, the even deeper causes could be found in the personal investment in whiteness, with all of its catastrophic costs. “After this the descent to Hell is easy,” DuBois warned.

As he had in The Souls of Black Folk, DuBois employed the metaphor of the “veil” to symbolize the color line. But he also made vividly clear that for Black people race was not an abstraction. The “veil” in Darkwater is harsher, more forbidding, and more deeply rooted in America’s violent racial history than in Souls. “There is Hate behind it, and Cruelty and Tears,” DuBois observed. “As one peers through its intricate, unfathomable pattern of ancient, old, old design, one sees blood and guilt and misunderstanding. And yet it hangs there, this Veil, between Then and Now, between Pale and Colored and Black and White—between You and Me.” This system of racial caste resulted in the denial of opportunity for Black people at the moment of birth, thwarting their genius and potential.

As DuBois wrote in the chapter “The Immortal Child,” devoted to the future of Black youth, “We know in America how to discourage, choke, and murder ability when it so far forgets itself as to choose a dark skin.”

The veil also killed. In order to express the emotional toll of racial violence and the depths of Black suffering DuBois turned to verse and short fiction. The book’s first poetic interlude is “A Litany at Atlanta,” which he initially wrote on September 23, 1906, on a train as he rushed home to protect his family from white mobs that had attacked the city’s Black community. “Doth not this justice of hell stink in Thy nostrils, O God? How long shall the mounting flood of innocent blood roar in Thine ears and pound our hearts for vengeance?,” DuBois asks in a cry to the heavens.

The short fictional pieces in Darkwater provide another way to convey the violent hypocrisy of white supremacy and white Christianity specifically. One of the most powerful is the chapter “Jesus Christ in Texas.” It was first published in 1911 and originally titled “Jesus Christ in Georgia.” For Darkwater, DuBois changed the location to invoke the horrific 1916 lynching of Jesse Washington in Waco, Texas, which the NAACP spotlighted as part of its national antilynching campaign. In the story, Jesus arrives in the form of a mixed-race stranger, “tall and straight,” whose hair “hung in close curls” down his dark face. But even this divine presence is not enough to prevent the lynching of an escaped Black convict accused of attacking a white woman.

For DuBois, grappling with the meaning of race was essential for understanding the future of democracy. DuBois believed deeply in democracy as both a method of governance and a way of life. But as the aftermath of the war laid bare, America had, he argued, betrayed its ideals and forfeited its claim to world leadership. “Instead of standing as a great example of the success of democracy and the possibility of human brotherhood,” DuBois lamented, “America has taken her place as an awful example of its pitfalls and failures, so far as black and brown and yellow peoples are concerned.”

Darkwater highlights three issues that DuBois saw as particularly urgent for the salvation of American democracy: education, the right to vote, and the political and social status of women. “Is democracy a failure?” DuBois asked, to which he replied, “Train up citizens that will make it succeed.” Instead of investing in war and consigning Black people to a life of labor and exploitation, the nation should invest in education and train Black people to be enlightened participants in American democracy. But African Americans would also need full access to the ballot, the lifeblood of democracy, which by 1920 had been systematically stripped from them. As DuBois passionately wrote, “If America is ever to become a government built on the broadest justice to every citizen, then every citizen must be enfranchised.” And that included women. By the time of Darkwater’s publication, the Nineteenth Amendment had been passed by Congress but not yet fully ratified by the states.

In his chapter “The Damnation of Women,” DuBois declared his full support for women’s right to vote, telling his readers, “When women ask for the ballot, they are asking, not for a privilege, but for a necessity.” He emphasized the need to protect and empower Black women. “As I look about me today in this veiled world of mine, despite the noisier and more spectacular advance of my brothers,” DuBois wrote, “I instinctively feel and know that it is the five million women of my race who really count.”

DuBois looked beyond the United States as well to consider what democracy would mean to Africa in the wake of the war. As early as 1915, DuBois had diagnosed the roots of the world war in the competition between the various European belligerents for imperial control of Africa and its resources. With the war over, DuBois insisted that the principles of self-determination be applied to African peoples as well. He proposed the creation of a new “African State,” composed of Germany’s former colonies and administered through the League of Nations with the full participation of “educated and trained men of Negro blood.” His bold vision would constitute the beginning of Africa’s emergence into the modern world and the foundation of “a new peace and a new democracy of all races” in the postwar world.

Darkwater sold briskly, becoming the object of enthusiastic acclaim and intense criticism. Reactions, not surprisingly, fell along racial lines. “You have accomplished what seemed impossible, you have given us a better book than Souls of Black Folk,” lauded DuBois’s close friend and president of Atlanta University John Hope. The Black intelligentsia, along with working-class Black folk in the North and the South, praised the book, reaffirming DuBois’s standing as the preeminent voice of the race. White critics, however, denounced DuBois’s bitterness and perceived violent hatred, with some going so far as to liken it to a Bolshevist call for revolution. DuBois dismissed these detractors, and Darkwater remains one of his most widely read books.

DuBois would certainly have mixed feelings about the continued relevance of Darkwater a century later. He would no doubt take satisfaction in his work continuing to have meaning. He would also no doubt be disheartened that so much of what he wrote in Darkwater in 1920 remains true today.

DuBois died in 1963, on the eve of the March on Washington, as the civil rights movement he helped build reached a crescendo. In 2020, we have seen how the struggle for democracy and racial justice continues. But we do not need to ask what DuBois would have to say about the moment we are in.

Indeed, with Darkwater, he has let us know. While certainly shaped by its context a century ago, the book addresses themes and challenges that transcend time, most urgently the need to recognize Black people as equal human beings and participants in the nation’s democracy. “What a world this will be when human possibilities are freed, when we discover each other, when the stranger is no longer the potential criminal and the certain inferior!,” DuBois movingly wrote. His life and work serve as important reminders of the depths of our wounds, the healing power of knowledge, and the possibility of a better world.