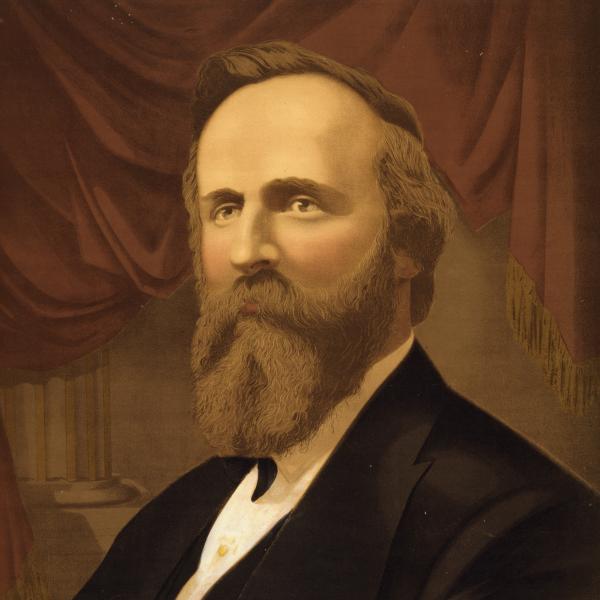

More than 140 years ago, President Rutherford B. Hayes won the election of 1876 by committing to end Reconstruction. A highly controversial political compromise preceded by disputed electoral votes and involving questionable deals with Southern Democrats, it was also a major about-face for the Ohio Republican.

As a congressman and governor, Hayes had long supported Reconstruction. As president, in a speech at the Hampton Institute in 1878, he called it “a great duty” of the American people to educate former slaves and raise them to “the full status of American citizenship.” But when he removed federal troops from Louisiana and South Carolina, in the naïve belief that the absence of coercion would lead to equality under the law, President Hayes ushered in a new and very difficult era for African Americans.

Still, one goal Hayes didn’t accomplish as president—invigorating black education—he worked for as an ex-president. By supporting the Hampton and Tuskegee Institutes through the Slater Fund, a charitable organization whose board he led, Hayes created pathways to vocational education as promoted by Booker T. Washington. And, through an interesting sequence of events, Hayes came to play a significant role in the educational progress of another important black figure, W.E.B. DuBois.

The relationship between W.E.B. DuBois and Booker T. Washington has long been presented as a pedantically useful binary. The two promoted different methods of progress for African Americans, with Washington on the side of vocational education and DuBois on the side of a liberal arts education.

“As each one shaped his program,” writes Mark Bauerlein of Emory College, “their respective talents turned them into figureheads and established a polarity that helped orient others to the ‘race question.’” However, in an analysis of letters between the two men, Bauerlein has shown that over many years, “DuBois and Washington maintained a mutual respect and worked together.” The first letter from DuBois to Washington on July 27, 1894, is, in fact, a request for a job at Tuskegee. Though DuBois accepted a position at another institution before Washington could offer him one, Bauerlein shows how their correspondence over the years illustrates their “respect—and rising suspicion.”

Washington interacted with former president Hayes through the Slater Fund, much of whose budget, particularly in the 1890s, went to the Tuskegee Institute, where Washington was principal, and the Hampton Institute, where Washington had previously taught. But Hayes also had a notable correspondence with DuBois and is credited with helping a young DuBois get a grant and loan to study in Europe. In the opinion of Herbert Aptheker, the editor of The Correspondence of WEB DuBois Volume I, it is in his correspondence with DuBois that Hayes may have performed “the greatest service of his career.”

The Slater Fund was established in 1882 by John Fox Slater, who donated $1 million for the industrial education of Southern blacks. As Hayes, a board member, wrote, it was agreed that the funding would be used “only at schools which provide some form for industrial education” as preparation for “manly occupations like those of the carpenter, the farmer, and the blacksmith.” The Hampton Institute in Virginia and the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama became models of this kind of vocational college, and, by 1900, the two schools received fully half of the Slater board’s funding.

As Roy Finkenbine writes, “Largely due to the support of the Slater board, industrial education became the dominant curriculum in Black schools during the 1880s and 1890s,” which was a change from the more liberal arts curriculum offered in black Southern colleges. In fact, the Slater board thought that a more liberal education was a path that would lead to black restlessness. Hayes, as the leader of the Slater Fund, had much power over where the money would be spent and on the decision to promote industrial education for Southern blacks.

Yet there are moments in Hayes’s speeches and diary entries that suggest he understood the importance of education that was not strictly vocational. “The deeper Hayes became involved in education,” his biographer Ari Hoogenboom writes, “the more he realized that in a democratic republic, wise laws and efficient administration depended on the educational level of the population.” Hayes spoke about this interest in education at the 1890 Lake Mohonk Conference on the Negro, which he is credited with initiating. In his June 4, 1890, opening address, Hayes called for attendees to partake in an “impartial investigation and earnest discussion of the best methods for uplifting the colored people in their industries, their home life, their education, their morality, their religion, and, in short, all that pertains to their personal conduct and character.”

Most attendees interested in education for Southern blacks favored industrial education, but a minority had the “presumption that what African-Americans mainly needed was plenty of general education, not special education different in nature from that administered to whites,” writes DuBois biographer David Levering Lewis. In his speech, Hayes himself praised the ascendency of general education in the South since the end of the Civil War. “After only twenty-five years of freedom, one-third of them—perhaps more—are returned in the census as able to read and write,” Hayes told the conference. “Not a few of them are scholars of fair attainments and ability, and in the learned professions and in conspicuous employments are vindicating their title to the consideration and respect of their fellow-men.”

In a diary entry from later that year, Hayes writes that he is reading all he can find on what he called the “negro question.” “I find nothing which overthrows or even tends to overthrow the position that education will help him wherever he needs help, will strengthen [him] where he is weak, and will aid him to overcome all evil tendencies. The question then is how best to educate him.”

In late October 1890, Hayes met with the board of trustees of the Slater Fund in New York and then traveled to Baltimore with Johns Hopkins president Daniel Coit Gilman to meet with a new agent for the fund, who lived in Richmond. During a stop in Maryland, according to the Baltimore Sun, Gilman took Hayes around Johns Hopkins to meet faculty and see the library and hospital. At the request of historian Herbert Baxter Adams, Hayes spoke to a class of students, offering some thoughts about Southern black education, which a reporter from the Sun ostensibly transcribed and the paper printed on Saturday, November 1.

After saying that the education of blacks had been much on his mind for several years, Hayes, according to the newspaper, offered a Slater Fund scholarship for the support of an education in the liberal arts but only for the exceptional black man:

If there is any young colored man in the South whom we find to have a talent for art or literature, or any especial aptitude for study, we are willing to give him money from the education funds to send him to Europe or to give him an advanced education, but hitherto their chief and almost only gift has been that of oratory.

The Sun ends its description of Hayes with some comments about his appearance, saying the former president “has gained in flesh since his last visit to Baltimore, and his hair and beard have grown whiter and scant. His complexion has the ruddy glow of health, and his eyes are bright and penetrating.”

The next day, November 2, the Sunday edition of the Boston Herald republished the Baltimore Sun’s article with a less positive slant. Under the headline “NEGROES IN THE SOUTH,” the Herald framed the story as “Ex-President Hayes Says Their Chief and Almost Only Gift Is Oratory.” Apparently, the Herald cared little for Hayes’s remarks, which they presented as a nasty aside from the president who ended Reconstruction.

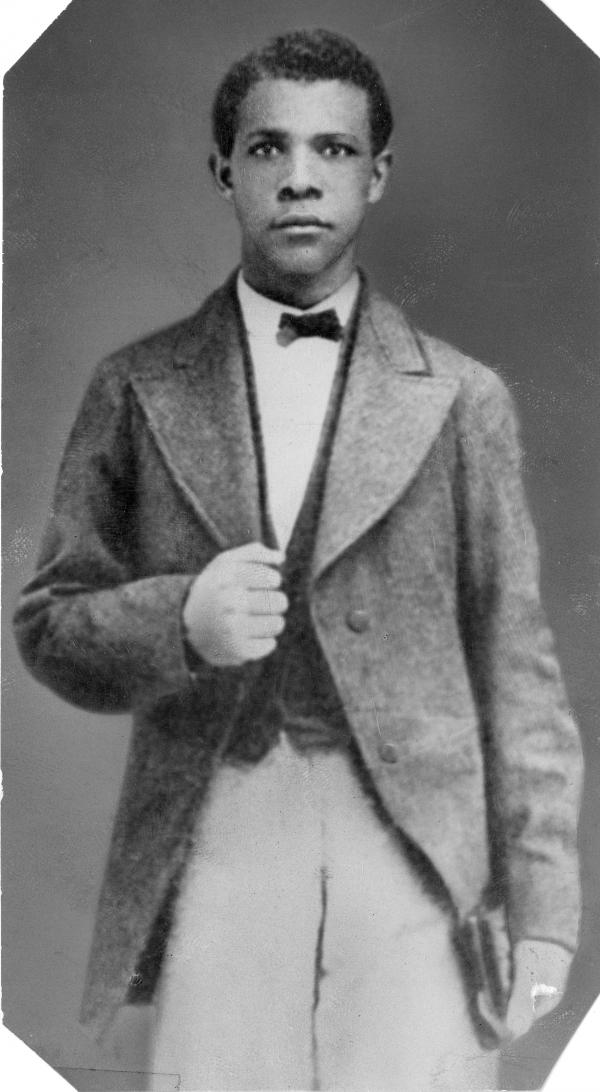

The possibility that Hayes’s remarks amounted to a challenge rather than a call for proposals had a particular effect on the one Boston reader who would be most interested in the opportunity. W.E.B. DuBois was working on his master’s degree at Harvard, which he would finish in 1891, and was hoping to complete a doctorate in the following two years. He knew that he wanted to study in Europe and had said as much in a spring 1890 letter to Harvard’s “Academic Council,” saying that he hoped to spend one year at Harvard and at least another year at a European university. As he writes in his memoir Dusk of Dawn, “Then came one of these tricks of fortune which always seem partly due to chance.”

On the night of either November 2 or 3, DuBois attended a card party, where he was told about the Herald article with Hayes’s comments. In his memoir, DuBois writes that it initially angered him. He was startled, DuBois wrote in a much later letter to Hayes, “that any agency of the American people was willing to give a Negro a thoroughly liberal education and that it had been looking in vain for men to educate.” He took the headline and comment about black oration personally, as described in his memoir. “This seemed to me a nasty fling at my black classmate, Morgan, who had been Harvard class orator a few months earlier, and indirectly at me.” But then, just a day or two later, DuBois wrote to Hayes to apply for the scholarship. It took some gumption, but at the time, writes DuBois’s biographer Lewis, “DuBois clearly thought of himself both as the embodiment of his race as well as something ambiguously superordinate.”

Using Harvard University stationery, DuBois wrote the name of “Hon Rutherford B. Hayes” on the top and then immediately pointed to the clipping from the Herald, which he pasted sideways in the middle of the first page of his four-page handwritten letter. Introducing himself as a graduate of Fisk University and a recent graduate of Harvard, he wrote that he was studying for a master’s and doctorate in political science. Despite these degrees, he said, he had also taken more traditional paths for a Southern black man: “I have so far gained my education by teaching in the South, giving small lectures in the North, working in hotels, laundries, etc., and by various scholarships and the charity of friends.” In other words, he was an example of the Southern black man Hayes promised to help and he planned to study “the history of African Slavery from the economic and social standpoint.” DuBois then listed his awards and fellowship as well as eleven professors and college presidents, including Professor William James and President Charles William Eliot.

As DuBois closed his letter, he called attention to the ex-president’s diminishment of his race. “If it appears to you upon investigation that I show ‘any especial aptitude for study,’” he wrote, sarcastically quoting the article’s account of Hayes’s remarks, “I respectfully ask that I be sent to Europe to pursue my work in the continental universities, leaving the details of the work to the recommendations of the appropriate professors in Harvard.” He added in his final paragraph, “If the extract above is not correct, I pray you will pardon my trespassing,” adding “Respectfully yours” before his signature.

It’s a curious sign-off. The two uses of “respectfully” and his request for “pardon” suggest DuBois was making a serious request; a crossed-out word between “pardon my” and “trespassing,” the only crossed-out word in the letter, suggests he didn’t care all that much what the former president thought.

Around this time, Hayes would have received another letter, written October 31, the day he was addressing students at Johns Hopkins. On Tuskegee letterhead, Booker T. Washington thanked the ex-president for a photograph: “Dear Sir: I want to thank you with all of my heart for your picture. It will always be a priceless treasure with me.” It was courteous, deferential, and brief. Also, it made a positive impression on Hayes. At the bottom of the one-page letter Hayes wrote down his opinion of Washington, calling him “perhaps the ablest and most useful Colored Man in the Country—Certainly a most worthy man.”

It is difficult to imagine that the two letters didn’t inspire a comparison between the already iconic Washington and the soon-to-become iconic DuBois, but Hayes did not seem to know DuBois before this time. Yet, on Monday, November 10, Hayes may very well have been thinking of the two correspondents when he commented in his diary: “Wrote letters all of the forenoon; too many for comfort. And how absurdly prolix many correspondents are! One page is long enough.”

In Dusk of Dawn, DuBois wrote that he received from Hayes “a pleasant reply saying that the newspaper was incorrect” and that the Slater board had no plans to create a scholarship for a liberal arts student. Not to be deterred, DuBois gathered additional letters of recommendation, such as a letter from Harvard geology professor Nathaniel Southgate Shaler dated March 2, 1891, praising DuBois: “He seems to me decidedly the best specimen of his race we have had in our classes.” DuBois wrote again to Hayes on April 19, 1891, with more information about himself and, on May 6, 1891, he asked for a specific amount. In Dusk of Dawn, DuBois wrote that Hayes again responded that no funds existed though “he recognized that I was a candidate who might otherwise have been given attention.”

This time DuBois responded with, in his words, “a letter that could be described as nothing less than impudent and flatly accused him of bad faith.” On May 25, 1891, he wrote Hayes that “the injury you have—unwittingly I trust—done the race I represent and am not ashamed of, is almost irreparable.” Exaggerating the formality of Hayes’s remarks at Johns Hopkins, DuBois rebuked Hayes, telling him he spoke “before a number of keenly observant men who looked upon you as an authority in the matter, and told them in substance that the Negroes of the United States either couldn’t or wouldn’t embrace a most liberal opportunity for advancement.” By canceling the “experiment” before testing it with a case such as his, Hayes, said DuBois, was reinforcing the stereotype that blacks are at best good orators and not good enough to receive funds for “liberal education” but only “toward training plowmen.”

DuBois saved his unkindest cut for the end of his letter. Calling for an apology from Hayes not just to himself but “to the Negro people,” he all but called Hayes a charlatan: “I find men willing to help me thro’ cheap theological schools, I find men willing to help me use my hands before I have got my brains in working order, I have an abundance of good wishes on hand, but I never found a man willing to help me get a Harvard Ph.D.”

According to DuBois, Hayes once again apologized and committed to supporting DuBois’s candidacy the following year, encouraging him to reapply, which DuBois did in a letter to the Slater committee on April 3, 1892. In that letter, says Lewis, DuBois “carefully elaborated his educational plans for a year of study abroad, again reminding the fund that the question of his future was of more than ‘merely personal interest.’”

“I did not of course believe that this would get me an appointment,” wrote DuBois in his memoir, but he was wrong. In Hayes’s diary from April 12, 1892, his agenda for the Slater Fund meeting includes a recommendation of funding for DuBois. The Slater board met April 13 and aid to DuBois was approved; two days later, Hayes wrote DuBois, saying he would receive $750 for a year’s study in Germany, half in cash and half in loan.

According to his diary, on April 15 Hayes received a calling card from DuBois while at breakfast in New York City at the Astor House. DuBois says in his own memoir that as soon as he heard he’d received the money, “I remember rushing down to New York and talking with President Hayes in the old Astor House, and then going out walking on air. I saw an especially delectable shirt in a shop window. I went in and asked about it. It cost three dollars, which was about four times as much as I had ever paid for a shirt in my life; but I bought it.” Hayes, for his part, recorded the meeting with DuBois, saying he was “[v]ery glad to find that he is sensible, sufficiently religious, able, and a fair speaker.”

Former president Hayes died the following year, on January 17, 1893, while DuBois was studying in Germany. In an undated letter to Daniel Coit Gilman from Berlin, DuBois once again thanked the Slater Fund for his scholarship, adding, “I am especially grateful to the memory of him, your late head, through whose initiative my case was brought before you, and whose tireless energy and singleheartedness for the interests of my Race, God has at last crowned. I shall, believe me, ever strive that these efforts shall not be wholly without results."