Featured NEH-Funded Projects

Great Projects Past and Present

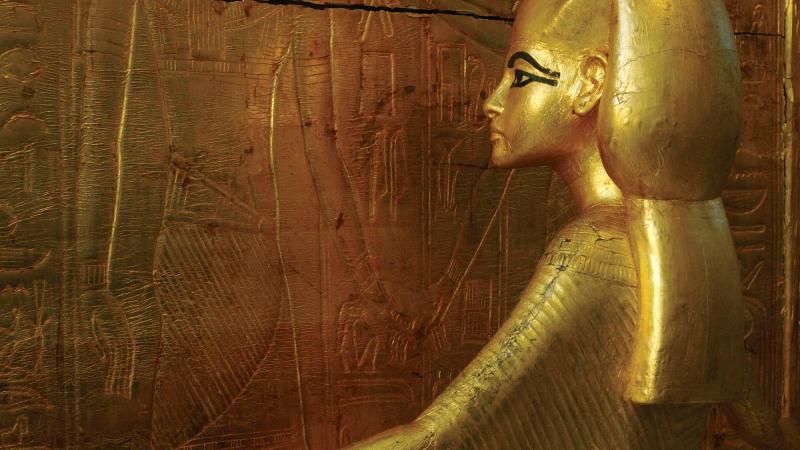

Buddha's head, digitally rendered in 3-D, as it would have appeared in the south cave of Northern Xiangtangshan.

Image Credit: Image by Jason Salavon and Travis Saul.

NEH grantees teach warrior-scholars. They preserve endangered languages. They show the history of the civil rights struggle through film and discover what life was like for early colonists in Jamestown. They open a window onto our history and our future. Here are a selection of NEH-funded projects that have shaped what we know about ourselves and our world.