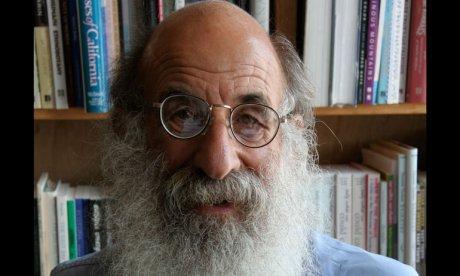

Malcolm Margolin

Courtesy of Heyday

Malcolm Margolin

Courtesy of Heyday

September 18, 2012--National Endowment for the Humanities Chairman Jim Leach has awarded a Chairman’s Commendation to Berkeley writer and publisher Malcolm Margolin for making extraordinary contributions to his community by telling the story of California’s people and its resources with vision, commitment, and passion.

Margolin, executive director of Heyday, an independent nonprofit publisher, “brings a serious and jubilant lifelong commitment to publishing that has shaped our fundamental understanding of the people and places” that make up the state, said Ralph Lewin, president and CEO of Cal Humanities, the state council partner of the National Endowment for the Humanities. Margolin is a “national treasure and it is good to see him recognized as such.”

NEH Chairman’s Commendations are given to citizens who have made extraordinary efforts to bridge cultures, promote civility, preserve our legacy and advance humanistic endeavors. Margolin was the second American so honored. The first Chairman’s Commendation was issued to Philip J. Lampi, a researcher at the American Antiquarian Society who has spent a lifetime researching and compiling local, state, and national voting records from 1787 to 1825.

Heyday publishes about twenty-five books a year that help celebrate and preserve knowledge of a California that might not otherwise be known. Margolin specializes in books that explore California history, natural history, literature, art, and ethnic diversity. He has published Gary Snyder, Pulitzer-prize winning author of Turtle Creek and other books; Wallace Stegner, winner of the Pulitzer Prize and National Book Award; Rebecca Solnit, author of 13 books; Robert Hass, former US Poet Laureate and Ursula LeGuin, the fantasy and science fiction writer. At the same time Heyday's list includes work from many first time writers from neglected areas of California.

“I love people’s kitchen voices,” he says, “the voices they use when talking to their families. “

Today, in his seventh decade, he has recently founded new writing awards, a new annual literary anthology, sponsored more than two hundred outreach efforts throughout the state, and launched a new bookstore and community space in partnership with the California Historical Society.

Margolin started out as a writer and moved gradually into publishing . He grew up in Massachusetts, son of a Lithuania-born homemaker and an American father. As a young man, he attended the Boston Latin School and Harvard College, where he majored in English. After graduation, two years in Puerto Rico, and a trip to San Francisco during the Summer of Love, he bought a $300 Volkswagen bus and headed West for good.

Supporting himself by writing for such publications as Science Digest and Nation magazines, Margolin and his wife, Rina, camped at Big Sur, armed with a copy of a book, Stalking the Wild Asparagus,wintered in Seattle, built a house out of driftwood on Vancouver Island, and visited Portland and Mexico before settling in Berkeley.

Margolin was working for the park district on trail maintenance when he started to get book contracts for volumes on parks, ecology, and native Americans. He typeset his second book himself, storing the volumes under his children’s beds, and gradually moved into publishing, founding Heyday, an independent nonprofit publisher and cultural institution in 1974.

In 1978 he published The Ohlone Way, a story of the people of the San Francisco Bay area. Its introduction begins: “Before the coming of the Spaniards, Central California had the densest Indian population anywhere north of Mexico. Over 10,000 people lived in the coastal area between Point Sur and the San Francisco Bay. These people belonged to about forty different groups, each with its own territory and its own chief. Among them they spoke eight to twelve different languages that were closely related but still distinct so that oftentimes people living twenty miles apart could hardly understand each other. The average size of a group was only about 250 people.”

Learning about Indians, says Margolin has “opened amazing doors—of pain, beauty, tortured history, humor. . . I would make a lousy Indian. I set out to be independent, but I became part of a community, and now I am dependent on them.

“I’m not out to increase my own stature by using other people’s cultures,” he said. “I’m like a stage manager. I want to keep the place clean, make sure there is not too much gum under the seats, let them have the beautiful ideas.”

“This is not a dog eat dog world,” he said, “or I would have been eaten a long time ago.”