Even though it can be said that many stock characters from American war literature people the pages of the NEH-funded anthology Proud to Be, they are always creatively updated and placed in circumstances far removed from the pages of, say, The Naked and the Dead, Catch-22, or even Going After Cacciato. Yes, there’s the ill-tempered company clerk and the larger-than-life staff sergeant with secrets hidden away off base somewhere, and the aspiring chef from the Bayou who experiments with a variety of seasonings for MREs (meals ready to eat), but there are also characters such as the sufferer from posttraumatic stress disorder trying to run a few errands back home and finding it harder than any obstacle course he had to run in basic training. Series editor Susan Swartwout writes in the foreword to the book—copublished by the Missouri Humanities Council and Southeast Missouri State University Press—that from the stories, poems, essays, interviews, and photographs in this volume, the fourth, subtitled Writing by American Warriors, she “learned that a veteran’s coming home to loved ones and civilian life can be yet another battle with its own version of firestorm.”

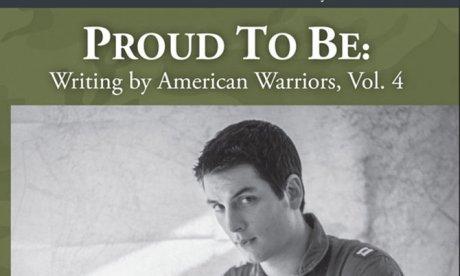

In an essay by Vietnam War vet Jay Harden, we discover what he found out about himself after enlisting: “I went to war for one unconscious reason: to be a secret hero to myself.” He considers himself lucky to have returned, however, with his sense of “childlike wonder that balances out the rest of our lives.” He writes, “Though I am now a grizzled old warrior, I still know how to laugh and play with my grandchildren as one of them.” In addition to his essay, Harden contributed a photo—“Planning for Peace”—which garnered first place in the photography category and appears on the anthology’s cover. It’s a self-portrait that captures his cautious self-assurance and quiet professionalism. The image is of Harden the navigator, preparing for his next mission, his flight helmet in the foreground. He takes a brief moment to look up from his work and toward the lens in three-quarters profile. The viewer notices Harden’s partially blocked name tag—serving as a subtle signature for the work—his wedding band, and the knowing look in his eyes, which are accentuated by a band of light on the wall in the background. It’s a portrait that supplies a narrative as strong as any essay, poem, or short story in the anthology.

The selection from war bards is eclectic, ranging from a rhyming 28-stanza tribute to a registered nurse/poet’s father and the crew of a downed WWII B-24, to a free-verse account of a soldier’s sorrow and horror at killing a “girl-child”: “I thought I was killing a warrior-woman . . . Your weapon was almost bigger than you.” The volume’s prize winner in its poetry category, Nicholas J. Watts, penned a free-verse study of the “dark places / where war still rages,” titled “nights.” Each stanza begins with the one-word verse “nights,” followed by terse, gut-wrenching admissions of guilt and dislocation. In “N.B.C.—4 report follows,” Charlie Sherpa borrows a standardized Army report format for indicating the boundaries of contaminated land. A leap of imagination allows Sherpa’s narrator to compare the suburban lawns of his present, treated with weed-killers and demarcated with little flags, to “acetate overlays” bearing pins for “troop movement.” The final stanza warns, “All friendlies, be advised: / Chemical weapons have been employed / against the insurgent dandelions.” Bryan Nickerson’s six-line “Bullet” follows the brief, swift, and deadly passage of the title’s eponymous projectile from magazine to chamber, “down the barrel,” “through the air,” and “into the chest of / the Afghan next to me.”

The short stories in this volume can be galvanizing. Christopher Lyke’s fiction winner “No Travel Returns,” one reviewer has remarked, “weaves a braided narrative of loss and return and fighting against—or maybe for—the routine.” Something is coming due, a tarp has been thrown over bad things in the past, and promises had been made to the gods—all of which lead to an ominous, thought-provoking final line. A must read. Also in the must-read category is “All Marines Are Green,” a poignant reminder of our common lot in war and peace, regardless of race.

Victoria Otto Franzese’s interview with her father, a WWII veteran who served as a medic during the Battle of Anzio and was captured by the Germans, has the makings of a screenplay for a breathless war story. Victor Bacon Otto escaped from a boxcar while being transported with other Americans to Germany, joined a group of Italian Partisans, and during the battle for Florence slipped away and made it back across the advancing American line. During his time in Italy, he had received rudimentary training as a medic, but the skills needed to endure his capture and plan his escape were more the stuff of instinct. Franzese’s account of her father’s ordeal reminds us of the importance of making a timely record of the memories of those who served as long ago as the 1940s. Victor Bacon Otto died in 2010 but not without leaving us an invaluable narrative of his experiences.

Many anthologies strive to be at least one of the following: representative, creative, compelling, entertaining, or honest. Proud to Be marches to the beat of all five.