The landscape surrounding Flagstaff, Arizona, is rife with multiple personalities. South of the San Francisco Peaks mountain range and north of the Sonoran Desert, at more than 6,500 feet above sea level, the region—officially part of the Colorado Plateau—merges dense forest and sparse scrubland. Juniper trees rise near yucca plants. Ponderosa pines thrive beside prickly pear cactus. Cutting through the region, twelve miles from the city, Walnut Canyon was, and remains, a thriving repository for this lush and contradictory blend of wildlife.

Now preserved as Walnut Canyon National Monument, it is full of breathtaking vistas; from its rim, you can see the curve and flow of volcanic rock that runs hundreds of feet below. Climb below onto its trails for a closer look as curved divots in the rock walls emerge—home for a thriving civilization nine hundred years earlier.

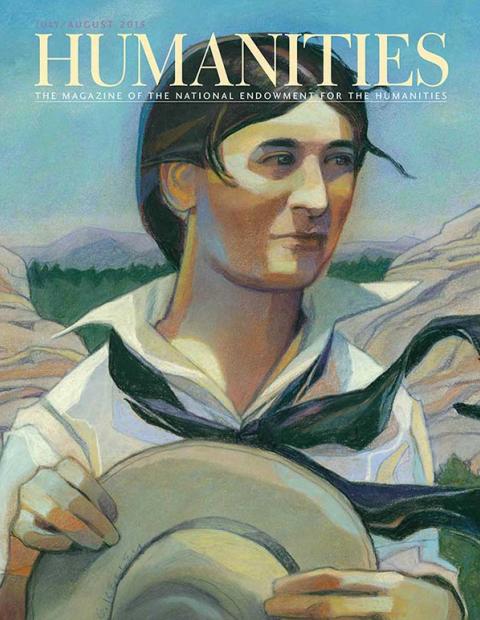

The author Willa Cather arrived in Flagstaff for the first time in the spring of 1912, eager to take all of this in. At that moment she was a successful writer, but uncertain of her next step. She was working as a writer and editor at McClure’s magazine, one of the most prestigious publications in the United States, and established as part of New York’s literary demimonde. But, as a novelist, she was struggling; she had produced one novel that she was dissatisfied with. After this trip, she would all but disown it.

Her first stop in the Southwest, Winslow, Arizona, held little promise for emotional or literary transformation—she bemoaned the “ugly little western town” in a letter. But her stop in Walnut Canyon shortly after proved inspirational in a way that would have a long reach across her career. It gave her imagination a jump-start that prompted her to complete her first mature novel, 1913’s O Pioneers!, which established her as the premier novelist of the Great Plains. The trip also began a love affair with ancient cliff dwellings and the desert that would play a central role in later novels such as 1925’s The Professor’s House and 1927’s Death Comes for the Archbishop.

But the most powerful and direct effect emerged in the first novel she began after returning from Walnut Canyon. In 1915’s Song of the Lark, Cather conjured the life of an ambitious young opera singer, Thea Kronborg, who was chafing at the pressures of city life before a trip to “Panther Canyon” in Arizona rewired her emotionally and intellectually, suggesting a direction for her life. Contemplating the Sinagua people who occupied those cliff dwellings centuries past, Thea is thunderstruck by a new sense of “older and higher obligations.” Cather herself, amid the push and pull of the landscape and her life as a city journalist and a child of the Great Plains, would arrive at a similar conclusion.

Cather was thirty-eight years old on April 12, 1912, when she arrived in Winslow to visit her brother, Douglass, who worked for the railroad there. She was on leave from McClure’s, where for the past six years she had risen to the position of managing editor—a rare accomplishment for a woman in American journalism at the time. She had also established herself as a fiction writer with stories like “Paul’s Case,” and had just published her first novel, Alexander’s Bridge, a tale of a Boston engineer, though she felt ambivalent about the book and it received modest reviews. So, more than just visiting a sibling, she was determined to find a new start. As she wrote in a letter to her friend Elizabeth Shepley Sergeant later that month, her goal was to “fade away in search of that seemingly simple but really utterly unattainable thing, four walls in which one can write.”

Cather was a New Yorker at the time, living in an apartment on Bank Street in Greenwich Village, after launching her career in Pittsburgh, where she had taught and wrote criticism for local papers in addition to writing short stories and poetry. But the West had a strong pull on her for her entire life: Raised in Virginia, she spent her adolescence in Red Cloud, Nebraska, attended the University of Nebraska, and had visited her brother Roscoe in Wyoming. And though it was her first visit to the Southwest, the region had occupied her thinking and her fiction for some time, thanks in part to her work at McClure’s. “She had a lot of contact with the blossoming invention of the American Southwest by short-story writers; she was editing stories by writers who were trying to create this genre of cowboy fiction that probably Zane Grey popularized most fully a few years later,” says John Swift, an English professor at Occidental College and Cather scholar. “So she was very familiar with the concepts of the Southwest—the myths of the Southwest, and she wrote bits and pieces of it into her fiction from very early on.”

The story of the Sinagua people who lived there circa 1200 CE was familiar to Cather—and indeed to much of the country, which heard about the cliff-dwellers from magazine articles and railroad tours. “She was part of the culture, there,” says Ann Moseley, editor of the critical edition of The Song of the Lark. “I do think her interest was probably greater than most, but it was pretty common.” The Native Americans had occupied the area for about a hundred years, surviving as hunters and farmers in a parched region. By 1250 they had departed for unknown reasons, most likely an extended drought, but the canyon attracted plenty of tourists who were eager to experience the breathtaking views of the twenty-mile canyon, explore the curved indentations in the limestone hills, and take pottery and other remnants as souvenirs. (Walnut Canyon was officially proclaimed a national monument in 1915, which put a halt to the thievery, or at least slowed it.)

For Cather, the trip was a success even before she made it to Walnut Canyon. “How splendid this part of the world is!” she enthused to her boss, S. S. McClure, in late April. After visiting the Grand Canyon, she was struck by the sense of isolation—an essential self-distancing—the area produced in her. “People are the only interesting things there are in the world, but one has to come to the desert to find it out,” she wrote to Sergeant. “And until you are in the desert, you never know how un-interesting you are yourself.” That shift in perspective would be an important one as she made her next trip.

Cather arrived in Walnut Canyon with Douglass in late May of 1912; they likely spent less than four days visiting the cliff dwellings, visiting the ranger cabin, and observing the wildlife. Her letters don’t pinpoint an exact revelatory moment when she was struck by a profound sense of human isolation, the past, nature, spirituality, and the possibility of annealing it all into art. But Cather ascribes just such a moment to Thea inThe Song of the Lark, using a shard of pottery that Thea discovers as metaphor for her awakening. As Thea bathes in the river at the bottom of the canyon, thousands of feet above sea level but hundreds of feet below civilization, she thinks, “What was any art but an effort to make a sheath, a mould in which to imprison for a moment the shining, elusive element which is life itself,—life hurrying past us and running away, too strong to stop, too sweet to lose?”

As Cather headed back home, she described being affected by the powerful sense of isolation the desert offered—but something besides mere isolation, too. “I long to tell you about wonderful Arizona,” she wrote to her friend Annie Fields. “I really learned there what Balzac meant when he said ‘In the desert there is everything and nothing—God without mankind.’” The trick would be to make fiction out of that sentiment.

One of the first things Thea notices entering the canyon is the landscape’s shift from forest to desert, how it occupies two different worlds: “The piñons and scrub begin only where the forest ends, where the country breaks into open, stony clearings and the surface of the earth cracks into deep canyons.” And once she enters the canyon—Cather may only have visited for a handful of days, but Thea Kronborg stayed for months—she spends much of her time contemplating the merger of nature and civilization, fine art and spirit. She analogizes the cliff dwellings to a modern city:

There a stratum of rock, softer than those above, had been hollowed out by the action of time until it was like a deep groove running along the sides of the canyon. In this hollow (like a great fold in the rock) the Ancient People had built their houses of yellowish stone and mortar. The overhanging cliff above made a roof two hundred feet thick. The hard stratum below was an everlasting floor. The houses stood along in a row, like the buildings in a city block, or like a barracks.

Urban life isn’t entirely erased from Thea’s mind—she describes the way “the high, sparkling air drank [her personality] up like blotting-paper.” But she’s also struck by what many a visitor senses there: A constant shuddering wind, thin air, bright sun sparkling off the yellow-white limestone walls, distant vistas. Some of the most powerful passages in the book are those in which Thea gives in to nature, becomes almost abstracted by it: “Here she could lie for half a day undistracted, holding pleasant and incomplete conceptions in her mind—almost in her hands. They were scarcely clear enough to be called ideas. They had something to do with fragrance and color and sound, but almost nothing to do with words.”

Moseley, in her critical edition of The Song of the Lark argues that such writing makes The Song of the Lark “an early modernist episode.” James Joyce’s Portrait of an Artist as a Young Man, which tracked a similar artistic transformation, was published the following year.

Even so, Thea is a young woman on a mission: To arrive at a decision about her singing career. As her suitor Fred Ottenberg tells her, “I’ve decided that you never do a single thing without an ulterior motive.” And once she arrives at that decision—that she will head to Germany to study and fully commit herself to opera—she sets the canyon aside abruptly: “They were tired of the desert and the dead races, of a world without change or ideas.” The East Coast Cather had reemerged; the magic and grace and power of the long-gone “Ancient People” had their utility, but clearly there were limits.

“You can play with the desert and love it and go hard night and day and be full of it and quite tipsy with it,” she wrote Sergeant upon her return to Pittsburgh. “And then there comes a moment when you must kiss it goodbye and go!” But something about the trip loosened her mind. Back in Pittsburgh she began working on “The White Mulberry Tree,” a story set in her native Nebraska. She then thought to combine it with “Alexandra,” a sketch she had written in 1911 and set aside. That combination—“a sudden inner explosion and enlightenment,” as Cather described it to Sergeant—was the genesis of O Pioneers!, the 1913 novel that would establish her as the foremost novelist of the American heartland.

With O Pioneers! Cather established a theme for her fiction: From then on, as her biographer James Woodress writes, she would “let the country be the hero” and set contrasts between “the wild land and the settled countryside, the early striving and the later materialism.” She dedicated much of 1913 and 1914 to applying that sensibility to The Song of the Lark, still juggling her art with more earthbound writerly duties—she had committed to ghostwriting McClure’s autobiography, a commission she found burdensome. But another assignment proved beneficial to the novel’s cause: In late 1913 she profiled three women opera singers for McClure’s and was particularly taken by Olive Fremstad, a Swedish-born soprano who was raised in Minnesota. In the article, Cather depicts Fremstad as an iron-willed person who fought a solitary battle for high art amid the barbarians. “She believes that the artist’s quest is pursued alone, and that the highest rewards are, for the most part, enjoyed alone,” she wrote. In Fremstad, the novelist had found a kindred spirit—and a model for her art.

She wrote “Three American Singers” in tandem with The Song of the Lark, which seemed to flow out of her in a rush: In a November 1913 letter to Sergeant, she wrote that the novel was nearly done, having produced “28,000 words in four jolly weeks.” A bout of blood poisoning, thanks to a cut from a hatpin, led to a brief hospital stay in February 1914. But otherwise the work went smoothly, and by March 1915 she had sent the manuscript to her editor at Houghton Mifflin, Ferris Greenslet, with high hopes for its success following the positive attention received by O Pioneers! “I think this book ought to be pushed a good deal harder,” she wrote, “because I think it has more momentum in it and will go further.”

While Greenslet and Cather tussled over changes to the manuscript, the cliff dwellings retained their pull on her: That summer she headed to Colorado with her friend Edith Lewis to visit Mesa Verde, home to the largest collection of cliff dwellings in the United States. That trip would later prove central to “Tom Outland’s Story,” the central section of her 1925 novel, The Professor’s House, just as the visit that she and Lewis made to Taos, New Mexico, on their way back east would help shape her 1927 novel, Death Comes for the Archbishop. During her week in Mesa Verde, she was again struck by the union of past and ancient civilizations, nature and culture. “For me the mesa was no longer an adventure, but a religious emotion,” her professor explains. “I had read of filial piety in the Latin poets, and I knew that was what I felt for this place.” Curiously, what the landscape does is inspire him to become a more diligent Western scholar, reading the Aeneid and mastering Spanish grammar. But Cather could never separate the grace of nature from its power to inspire productivity: Two years later, in Death Comes to the Archbishop, Cather would do much the same for the long arc of its hero’s life, who loved the desert while also attempting to tame it as a Catholic priest.

More immediately, Cather was eager to tip readers to the cliff-dweller elements of The Song of the Lark, suggesting to her publisher that they be a key part of the book’s promotion—she wrote a brief essay on Mesa Verde that was included in copies sent to reviewers and booksellers, describing how the ruins “stood as if it had been deserted yesterday; undisturbed and undesecrated, preserved by the dry atmosphere and its great inaccessibility.” She also proposed a nonfiction book on the Southwest to Greenslet—“It would be the only reasonably good book on that country ever done,” she wrote in September 1915, just weeks before Lark was published—but it never came to pass.

The Song of the Lark was published on October 2, 1915, to generally positive notices. H. L. Mencken said it represented Cather’s arrival into “the small class of American novelists who are seriously to be reckoned with,” and she wrote a grateful letter to a New York Evening Post reviewer who suggested, as Cather described, “that the cow-puncher’s experience of the West was not the only experience possible there.” But she was perhaps more enthused by Fremstad’s admiration for the book. “I felt rather as if I had received a decoration,” she wrote.

That, too, reveals Cather’s split personality—Cather loved the Southwest for its isolation and history, but it meant little to her unless it was set against the East, for its own culture and approval. “It’s a wonderful experience that she has in Panther Canyon,” says Swift about Thea. “But in fact, she leaves it behind her. And the last we see of her, she’s become a star of New York.”

None of which is to suggest that Cather didn’t truly care about the Southwest. But Cather also seemed uniquely capable of treating the inspirational power of the region as a kind of spigot she could turn on and off as she—or her fiction—demanded. “Unless you had lived all over the West, I don’t believe you could possibly know how much of the West this story has in it,” she wrote to Greenslet when she submitted the manuscript of The Song of the Lark. “I can’t work over it so much that I ever blunt the ‘My country, tis of thee’ feeling that it always gives me. When I am old and can’t run about the desert anymore, it will always be here in this book for me; I’ll only have to lift the lid.”