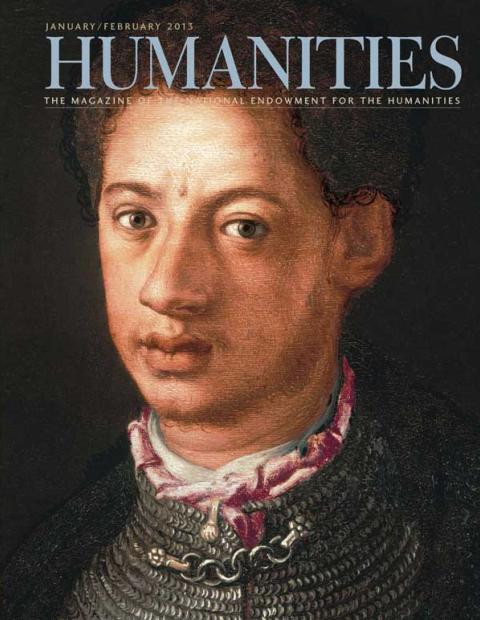

Recently, a young African-American reader told me she did not see herself in the covers of HUMANITIES. She was talking mainly about the magazine’s coverage of European culture, which she assumed is always about white people. I say this not to criticize. I make the same assumption.

But a new exhibit at the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore asks us to think again. The curators have turned their eyes to examples of diversity in Renaissance art, not simply background figures painted in darker hues, but subtle evidence of racial mixing in portraits of European elite. Mary Kay Zuravleff reports.

The conversation with our reader made me wonder whether even I, the magazine’s editor, see myself in the magazine’s stories, which are, of course, drawn directly from projects funded by NEH. The answer is, well, sometimes.

Two hundred years ago, Jane Austen published Pride and Prejudice, a novel about early nineteenth-century middle-class English girls hoping to find matches. In reading Meredith Hindley ’s essay on Austen’s writing of this masterpiece, I can say, yes, I do see myself in such stories. In reading Pride and Prejudice, I feel a sibling-like bond with Elizabeth Bennet. In reading about Austen’s struggle to make ends meet and be a writer, I identify with Jane herself.

And in reading or watching Hamlet, I identify with the prince of Denmark. Who doesn’t see himself in Shakespeare’s comedies and tragedies, which receive a wonderfully intelligent gloss in the new NEH-supported television series Shakespeare Uncovered. If your only idea of a literary documentary is a fixed shot of an old professor in a wing-backed chair holding forth from his study, you must check out this six-part series from WNET, which was developed in partnership with the BBC.

In reading about the Civil War it is easy now to see the moral greatness of those who crusaded against slavery, but the abolitionists were, in the days before the Civil War, radically out of sync with the American mainstream. William Lloyd Garrison burned the Constitution and argued for the North to secede. Indeed, the great abolitionist was anti-Constitution and pro-secession. Watching the new NEH-supported documentary on the abolitionists, it is hard to see oneself in the story of William Lloyd Garrison.

But I am heartened to learn about the Mormon students at Utah Valley University who, in Jean Cheney’s article, learn to see themselves in the great philosophical tradition that stretches from the Bible and the ancient Greeks to Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, and even some contemporary philosophers. I am not a Mormon, but I can relate.