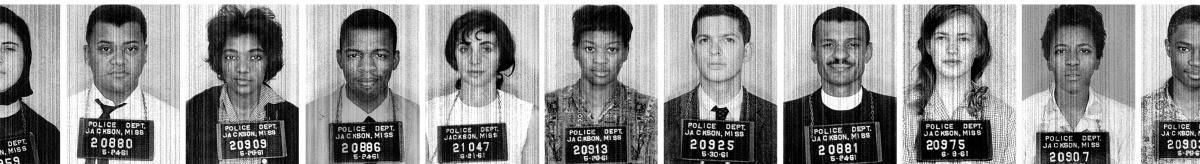

Hundreds of mug shots, side by side, row by row, fill a movie screen over and over again; young faces, some still in high school, beaten and arrested because they dared to ride a bus or step into a terminal. There was Joan Trumpauer, a nineteen-year-old secretary in Washington, D.C. After she became a Freedom Rider, she spent months in Parchman State Penitentiary, the harshest prison in Mississippi. Upon her release she went back to college and then in 1964 worked as an organizer of the Freedom Summer. Historian Raymond Arsenault collected all the vital stats on Trumpauer: She later worked for the Smithsonian and elsewhere in the federal government. Today, her married name is Mulholland, and she teaches English as a second language at an elementary school in Arlington, Virginia.

And there was Jim Zwerg, who was a Wisconsin student on exchange at Fisk University when he became a Freedom Rider. Arsenault has his story too.

Zwerg was hospitalized after a mob beat him with bats and pipes in Montgomery, Alabama. He became a minister in the United Church of Christ, and then switched career tracks in 1975 to become a personnel manager for IBM. He later worked at a hospice in Tucson, and still lives in Tucson, where he has retired.

Arsenault collected 436 such stories. An appendix running fifty-four pages at the back of his nearly 700-page 2006 book Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice provides a biographical dictionary of every Freedom Rider he could find, documenting each rider on each ride, giving their age, gender, hometown, profession or college where they studied, and what became of them. The rest of the book painstakingly records details great and mundane of all the events concerned with the Freedom Rides, when between May and December 1961 a group of people—students, clergy, and others of all colors, most under thirty years old—descended by bus and train into the Deep South to confront segregation in interstate travel.

Arsenault’s book is a dense read. In exacting detail, it gives a day-by-day account—sometimes hour-by-hour—of the events and people along the way, from the original unintentional Freedom Rider, Irene Morgan, whose case went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1946, to the Southern segregationists who dug in and upheld local customs over the laws of the federal government.

No one had tackled the whole story of the Freedom Riders before Arsenault, and he did so with a vengeance. No detail was considered insignificant—he spoke with anyone alive who had ridden. We know what books they packed for the trip, who they called, what they ate the night before they rode, and whom they sat next to on the bus. Some names you may recognize, like Georgia congressman John Lewis or former Black Panther leader Stokely Carmichael, but most you wouldn’t. They are extraordinary people who have led ordinary lives.

Interviews with Mulholland, Zwerg, Lewis, and others appear in the upcoming documentary Freedom Riders, directed by Stanley Nelson and airing on WGBH’s American Experience May 16. It is a feat of moviemaking—distilling sixty-three separate rides into one dramatic narrative. Although Nelson relied on Arsenault’s meticulous research (Arsenault was also a consultant on the film), the movie doesn’t try to tell the same story as the book. “One of the central things I tried to do was to have as much detail as I could,” but not so much, says Nelson, “as to make it confusing.”

“Film is remarkably unfriendly to density,” says American Experience’s executive director Mark Samels. “Authors are shocked how we boil down all the spoken words in a film from what are the words in a book. It’s what we do. One of the real breakthroughs that Stanley brought was to create one representative ride that stood for all the other rides.”

Nelson’s film focuses on the first ride, but even that is not so simple, because it is actually the combination of four different bus trips and forty-one riders. On May 4, 1961, after days of intense training in nonviolence techniques, the Congress on Racial Equality sent thirteen riders, black and white, male and female, on one Trailways and one Greyhound bus, from Washington, D.C., to New Orleans. Neither bus made it to New Orleans. In fact, as Martin Luther King Jr. had predicted, they never made it out of Alabama. One bus was firebombed in Anniston, and the other, after its passengers were attacked and beaten in Birmingham, was stranded at the terminal, unable to secure a driver brave enough to take them on the next leg to Montgomery. With dwindling options, the band of demoralized riders boarded a plane to New Orleans, believing that it was the end of the Freedom Ride.

Unbeknownst to them, a group of student activists in Nashville were deciding to drop out of school and head to Birmingham to continue the ride. Ten volunteers left Nashville the next morning on the 5:15 a.m. Greyhound bus bound for Birmingham; thirteen more got on a second bus the following day. Despite setbacks—like a midnight police escort back to Tennessee and a Ku Klux Klan siege at a church rally in Montgomery—they eventually made it to Jackson, Mississippi. Here, they were promptly arrested for disturbing the peace and sent to Parchman State Penitentiary. The riders caught the imagination of the nation and drew hundreds from all over the country to the Deep South to show their solidarity, making Jackson ground zero for the movement. Eventually, three hundred served time in Parchman: It became a badge of honor for the riders and a symbol of shame for Mississippi.

“How do you boil down the story to its essence and make sure it is the same story and not historically inaccurate?” Nelson poses. For one thing, a filmmaker has to be brutal with the editing knife, using only the interviews and events that work together best. “There were so many remarkable individuals, and not all of them could crowd themselves onto the film,” says Samels. Nelson explains the process as if directing a theatrical film and “there are two actors and one does a much better job in a scene, that’s the one you feature. Who gives us the story and can contribute to the story in the places we need? I try to look at the interviews as characters in the film.”

Take the dramatic moment when the Nashville students are debating whether or not to send riders to Birmingham. It turns out that the best narrator of this moment was someone not even in the room. John Seigenthaler was Attorney General Robert Kennedy’s man on the ground in Alabama, charged with putting an end to the rides for the sake of safety and America’s international image. It was Seigenthaler who placed a desperate call to Diane Nash, the student organizer in Nashville, urging her to call off the ride. He recalls it word for word:

And I felt my voice go up another decibel and another and soon I was shouting, ‘Young woman, do you understand what you are doing? You’re gonna get somebody . . . Do you understand you’re gonna get somebody killed?’ And there’s a pause, and she said, ‘Sir, you should know, we all signed our last wills and testaments last night. . . . We know someone will be killed. But we cannot let violence overcome non-violence.’ That’s virtually a direct quote of the words that came out of that child’s mouth. Here I am an official of the United States government, representing the president and the attorney general, talking to a student at Fisk University. And she in a very quiet but strong way gave me a lecture.

“Our original idea was to have the conversation cut back and forth from his remembrance to her remembrance, but his was so much more vivid,” explains Nelson. “When we tried to cut it that way, it didn’t work because he is so impassioned and remembered every single word of the conversation, and Diane didn’t even remember his name.” Seigenthaler appears many times in the film, telling the story from the perspective of the government and as a participant—Seigenthaler himself was beaten unconscious by the mob in Montgomery.

Yet impassioned narrative alone won’t make a movie. With limited time, a film director has to rely on visual material, not words, to tell the bulk of the story.

Joseph Postiglione, a photographer with the Anniston Star, took the iconic image of the Freedom Ride—that of a burning bus with its victims collapsed on the ground. Otherwise, there was very little visual documentation of the attack—the national media didn’t swarm in until after Birmingham. Postiglione had been tipped off by the KKK to be at the scene, but there was also an amateur filmmaker making his debut. As the melee surrounding the bus gained momentum, a twelve-year-old boy who lived nearby instinctively rushed to the scene with his new 8-mm. camera, a recent birthday present. It was a short-lived present—within weeks the FBI held hearings on the attack and confiscated the boy’s camera and film. While Nelson’s team was combing through the transcripts of the hearings they were stunned to come across a reference to this unknown camerawork. But would the FBI still have it?

“I think the FBI took it as a challenge,” says Nelson. “They said to themselves, if we confiscated it, we should have it. Eight months later they called and told us they found it.”

There were other pieces of good fortune. At the beginning, only the black press covered the rides, including photographer Ted Gaffney from Johnson Publishing, which produced Ebony and Jet magazines. (The mobs, of course, didn’t differentiate the official Freedom Riders from anyone else on the buses; consequently journalists were targets of violence, too.) According to Nelson, Johnson Publishing never sold their photos until now.

“They went back and found ten contact sheets with thirty photos each,” says Nelson. It was Gaffney’s photographs that provided the visual materials for the group’s preparation and early part of the ride.

But it is the candid first-person accounts that give the movie its most poignant moments. Nash, who now lives in Chicago, remembers her trepidation as the coordinator for the Nashville contingency: “That was a heavy responsibility because the lives and safety of people whom I loved and cared about deeply, who were some of my closest friends, depended on my doing a good job at that.” Mulholland, fifty years older but with a youthful countenance, recalls her humiliation upon entering Parchman prison. Guards stripped her clothes off and with gloved hands inserted Lysol into her privates. “That was really intimidating. Showed they could do anything they wanted to us, and probably would.”

The most vocal opponent of the rides was Alabama governor John Patterson, who had won election on a strong segregationist platform but had also endorsed John F. Kennedy for president. When the Freedom Riders came to his state, and even within a few blocks of the governor’s mansion in Montgomery, Patterson stood by and watched the mayhem. “We can’t act as nursemaids to agitators,” he said at the time. “You just can’t guarantee the safety of a fool, and that’s what these folks are. Just fools.”

Other adversaries came from within the civil rights community. “The civil rights leaders are not at the center of this story,” says Samels. “They are observers, observers who are not really pleased by this disruptive group of young people who are taking history into their own hands and refusing to stop in the name of reason and caution.”

There were unexpected allies, such as Floyd Mann, Alabama’s director of state police, who promised to protect the riders, and Janie Forsyth McKinney, who was twelve years old when she risked her own safety to bring water and help to the injured riders in Anniston. “It was the worst suffering I’d ever heard,” McKinney recalls. “I walked right out into the middle of that crowd. I picked me out one person. I washed her face. I held her, I gave her water to drink, and soon as I thought she was gonna be okay, I got up and picked out somebody else.”

McKinney’s testimony almost didn’t make it into the film. “That was our last round of interviews,” says Nelson. “We had the whole scene cut before we interviewed her, but she added a whole other dimension to the story. She added that it didn’t matter if you were from the white South, you had a choice. We had to cut her in.”

Not every story could make it in. In one incredible interview, Patterson admits how he regrets dodging an urgent phone call from President Kennedy, instructing his secretary to say he had gone fishing. “When I refused to take the call from the president, that was a very bad moment for me. If I had it all to do over again, I would take the call,” he says to the camera with uncharacteristic remorse. “It has haunted me ever since.” Patterson’s confession didn’t make the final cut.

“We made a decision early on that we were going to keep the film in that time, so you can’t talk about what you know now, you had to talk about what you felt at that time and what you saw at that time,” explains Nelson. “It’s a hard decision, but once you make it, it’s fairly simple when you are confronted by the dilemma of what goes in and what’s left out.”

Patterson’s mea culpa is offered as a special outtake on the film project’s website, along with more interviews, a video segment on the songs of the movement, a timeline, a roster of the rides, curriculum materials for teachers, clips from the film, and other materials relating to the history and inspiration behind the rides. Such “extras,” in fact, constitute a major set of ancillary materials and activities. A Freedom Riders exhibition, in partnership with the Gilder Lehrman Institute, is traveling to twenty venues across the United State during 2011, accompanied by public programs—many attended by original Freedom Riders. Six hundred and fifty educators will attend teaching workshops around the country on how to use the film in the classroom.

“This is the biggest multidimensional project that American Experience has ever taken on in its twenty-three years,” says Samels. “And it’s all built on the power of the story.” Samels says his favorite part of the project is the 2011 Student Freedom Ride, in which forty college students depart May 8 from Washington, D.C., to retrace the ride, accompanied by three of the original riders.

Over one thousand students from across the country applied for the spots. “We wanted to select students that will bring the lessons back with them,” says the project’s outreach coordinator, Lauren Prestilio. They will be blogging and placing videos and photographs on the website during the ten days of travel, so their friends, families, and classrooms back home can participate. And they will attend a screening of the film at the First Baptist Church in Montgomery, where in May 1961, fifteen hundred people attended a rally for the Freedom Riders and ended up trapped inside by three thousand violent protestors. It was a moment of convergence. The riders were there, as was the civil rights leadership in the form of Martin Luther King Jr. on the phone with Bobby Kennedy, and the opponents, and finally the federal marshals and National Guard, who were ordered to step in.

But it is an unlikely interview, with someone who wouldn’t make it into the history books, that illuminates the events of that night. “In 1961, I was eleven years old,” recalls Delores Boyd. “It was important that I go that night. The busload of Freedom Riders had been attacked, had been beaten. Many of them were still hospitalized at St. Jude. We were told that those who were able would actually be there. I’d heard Dr. King before, I’d heard Reverend Abernathy, so the excitement wasn’t just seeing the leaders, we were all wanting to see who are these courageous Freedom Riders. And probably we’d been there at least an hour, hour and a half, when we realized that this would be different.”