It may seem odd that a literary scholar and biographer such as myself should review a scholarly edition that has been on the New York Times best-seller list for nearly three months. The last time I looked, volume one of Autobiography of Mark Twain (edited by Harriet Elinor Smith of the Mark Twain Project at the University of California, Berkeley) was holding its own at number five on the list, just ahead of another comedian’s take on the human race, Jon Stewart’s Earth (The Book). Usually, these robust annotated editions are priced around $100 and have a print run of 1,500 or less. This one published by the University of California Press is priced to sell at $34.95, for which the buyer gets 760 pages of relatively small print (at least for a best-seller). And from what I’ve heard, the publisher had originally planned to print only 7,500, but has now sold hundreds of thousands of copies since its issue on November 15, Mark Twain’s 175th birthday. Such books are usually reviewed in scholarly journals at least a year or more after their quiet, almost secret publication. This one has already been reviewed prominently in the New Yorker and the New York Times as well as in newspapers as far away as Hong Kong.

One hundred years after his death on April 21, 1910, Mark Twain is having one of the busiest years of his afterlife. While he was still alive, he wrote satires about heaven (where the Prophets are as remote as rock stars) and the Garden of Eden (which Eve renames “Niagara Falls Park”), but he never could have imagined such a heaven (or hell) on earth as this. Last spring a number of books about him appeared—another biography, a book about his last four years as the “Man in White,” one about his rocky relationship with a woman who ran his household after his wife’s death, and a rehearsal of Twain’s western years in the Nevada Territory, a period also colorfully covered in Roughing It (1872). But the real fireworks were held for last. First, there appeared volume one of the Autobiography and then, soon after the first of the new year, we heard about the forthcoming publication of Professor Alan Gribben’s NewSouth edition of “Huck Light,” a combined edition of Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn in which the N-word is replaced by the word “slave.”

The Autobiography presents for the first time “Mark Twain’s authentic and unsuppressed voice” in his diaries and dictations, while the NewSouth edition will expurgate his most magnificent work, effectively pruning the novel of its historical irony. After all, Huck is not an abolitionist. He simply likes Jim better than the slave’s owner, and so determines to “go to hell” for his willingness to assist a runaway slave. General outrage has been expressed at the “bowdlerization” of Twain’s magnum opus. Yet the expurgation also says something about us in the twenty-first century. In the refusal of so many public school districts to teach Huckleberry Finn simply because of the N-word, we are threatening the lifespan of an American classic. It has been proposed to send Huck exclusively to college, but even there its future may be bleak. It is impossible, for example, to find “Nigger Jeff,” Theodore Dreiser’s finest short story, in any college anthology today. According to the website for the new edition of Twain’s classic, the expurgation is “intended to counter the ‘preemptive censorship’ that Dr. Gribben observes has caused these important works of literature to fall off curriculum lists nationwide.”

Mark Twain was no stranger to censorship, including self-censorship. He would change just about anything if he thought it threatened sales. He simply didn’t want a lowly editor to tamper with his prose, but he gave his friend William Dean Howells carte blanche over the final draft of Tom Sawyer. He removed the “raft” scene from the first edition of Huckleberry Finn because it had been published already in Life on the Mississippi, and he feared readers might mistake Huck for an old book and thus not buy it. He never allowed most of his satires on Christianity to be published, or his essay entitled “The United States of Lyncherdom,” for fear of hurting the general sales of his books, especially in the South. He would also not allow his autobiography to be published until one hundred years after his death. Well, that’s not exactly true. He published some of it in the North American Review in 1906 and 1907 , and there have been already three other scholarly editions of Twain’s autobiography. But the fact that the Autobiography was advertised in 2010 as containing material completely unavailable for one hundred years may have misled more than a few purchasers. It certainly aroused the pique of Adam Gopnik in the New Yorker and Garrison Keillor in the New York Times, both of whom compared the hype about the new edition of the Autobiography to the “Royal Nonesuch,” or the fraudulent undertakings of the Duke and the Dauphin in Huckleberry Finn. Yet even Keillor mentioned the new autobiography as something kept secret for a century.

Most, if not all, of what appears in volume one of the Autobiography, which will have two more volumes when complete, has in fact already been published in earlier editions of the autobiographical manuscripts. The differences are minor. For example, in cursing James W. Paige, the typesetter inventor who squandered $170,000 of Twain’s money, the writer refers to him much more indelicately in the latest edition. Apparently, some absolutely new material will make up the contents of the other two volumes—that is to say, material missing from the several editions of the autobiography that have already been published. Albert Bigelow Paine, Twain’s authorized biographer and literary executor, published a two-volume version in 1924; it was sanitized of any seeming improprieties. Paine, along with Samuel Clemens’s surviving daughter, Clara, faithfully protected the untarnished image of Mark Twain so that his books would continue to sell while safely protected under copyright.

Bernard DeVoto was responsible for the next appearance of the autobiography, this one containing only selections and limited to material that had been either suppressed or left out by Paine. His Mark Twain in Eruption appeared in 1940. Charles Neider, a tireless editor of Mark Twain, rearranged the material in chronological order in 1959, also adding new material. In their introduction to the newest edition, Harriet Elinor Smith writes: “The result of these several editorial plans has been that no text of the Autobiography so far published is even remotely complete, much less completely authorial.” The point here is that it was impossible to publish an “authorial” edition without knowing which parts of the “ten file feet of autobiographical documents” Twain intended to include in his final draft. The claim for the Autobiography of Mark Twain is that the editors at the Berkeley project found enough clues in “the great mass of autobiographical manuscripts and typescripts” to determine that its author had indeed a final plan for his book. And that plan was to avoid talking with absolute candor about himself and instead to talk about others. Whenever he tired of one subject, he would simply switch to a different one.

Whatever the case, much of what he dictated couldn’t be published until the subjects of his conversation with himself had died, thus the reason for the hundred-year caveat. The Autobiography is also not an autobiography in the usual sense because most of it wasn’t published during the author’s lifetime. The only “chapters” that saw light during Twain’s life appeared in carefully cleansed excerpts in the North American Review, subsequently collected in Mark Twain’s Own Autobiography (1990, 2010), edited by Michael J. Kiskis. The most touching sections are those in which the autobiographer prints patches of his daughter’s biography of himself. Susy Clemens, Sam’s brightest and most promising daughter, died tragically of spinal meningitis at the age of twenty-four in 1896.

The 2010 best-seller may initially surprise and ultimately overwhelm more than a few of its purchasers with both its bulk and intensity of editorial detail. Readers may also become bored with some of Twain’s commentary, though he is seldom less than entertaining. Some of his subjects are clearly lost to the oblivion of the nineteenth century, such details on the testimony in a lawsuit of Henry H. Rogers, the robber baron who helped protect his copyrights and other assets, or a narrative describing his writing about the burning of the clipper ship Hornet in Hawaii in 1866. The edition, as I see it, is the most comprehensive presentation of the extant autobiographical manuscripts and typescripts. It was edited primarily for scholars and students of Mark Twain and American literature. Its introduction and notes are the last word in accuracy and substance. When all three volumes are finally published, the Autobiography will probably replace, certainly update, all previous editions of the autobiography. Despite the fact that the originality of its revelations was exaggerated in the announcements of its publication on radio, television, and in the press, it clearly lives up to its title and description as Mark Twain’s authentic voice.

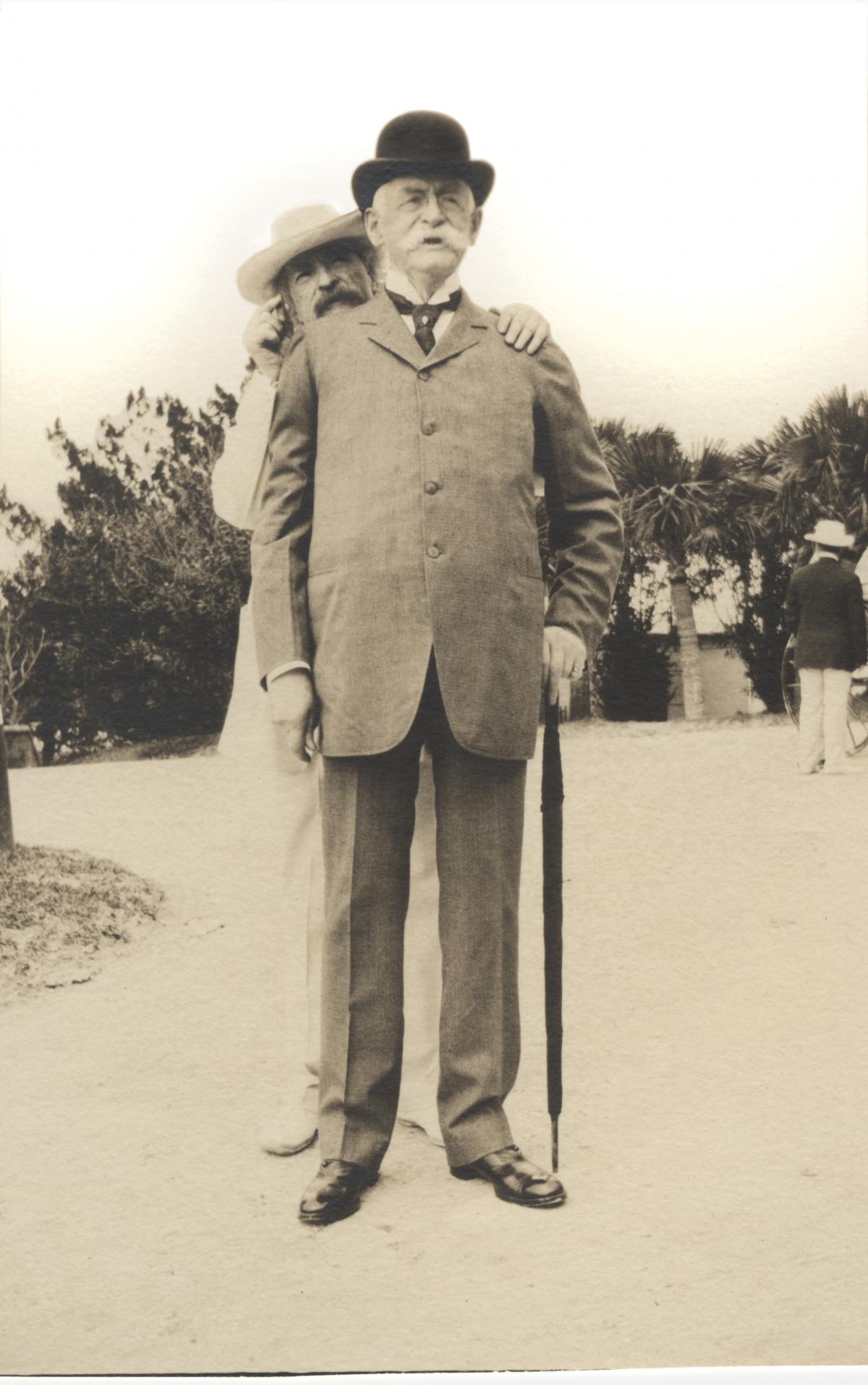

One example of that voice apparently informs us of Twain’s reason for including in Adventures of Huckleberry Finn the work of Karl Gerhardt, a third-rate sculptor whose study in Paris Clemens had financed beginning in 1881 after seeing specimens of his work in Hartford. Gerhardt had returned from the École des Beaux-Arts in 1884 looking for commissions. “There was nothing for him to do,” Twain wrote in his autobiography in September of 1884, “so he made a bust of me in the hope that it might bring him work.” That bust is possibly the same one that adorns the frontispiece of Huck’s “autobiography.” It is a profile of Mark Twain looking as classic as a Roman orator or general, perhaps inspired by Ulysses S. Grant, who was completing his Personal Memoirs for Twain’s publishing house as he lost a battle with cancer in the summer of 1885. In another gem, buried deep in the edition’s notes, we learn that Tom Blankenship, the model for the underclass Huck, did not—as Mark Twain wrote in his autobiography—become a justice of the peace in a “remote village in Montana,” but remained in Hannibal, was repeatedly arrested for stealing food, and died from cholera in 1889, only five years after the romance that immortalized this son of a town drunk had been published.