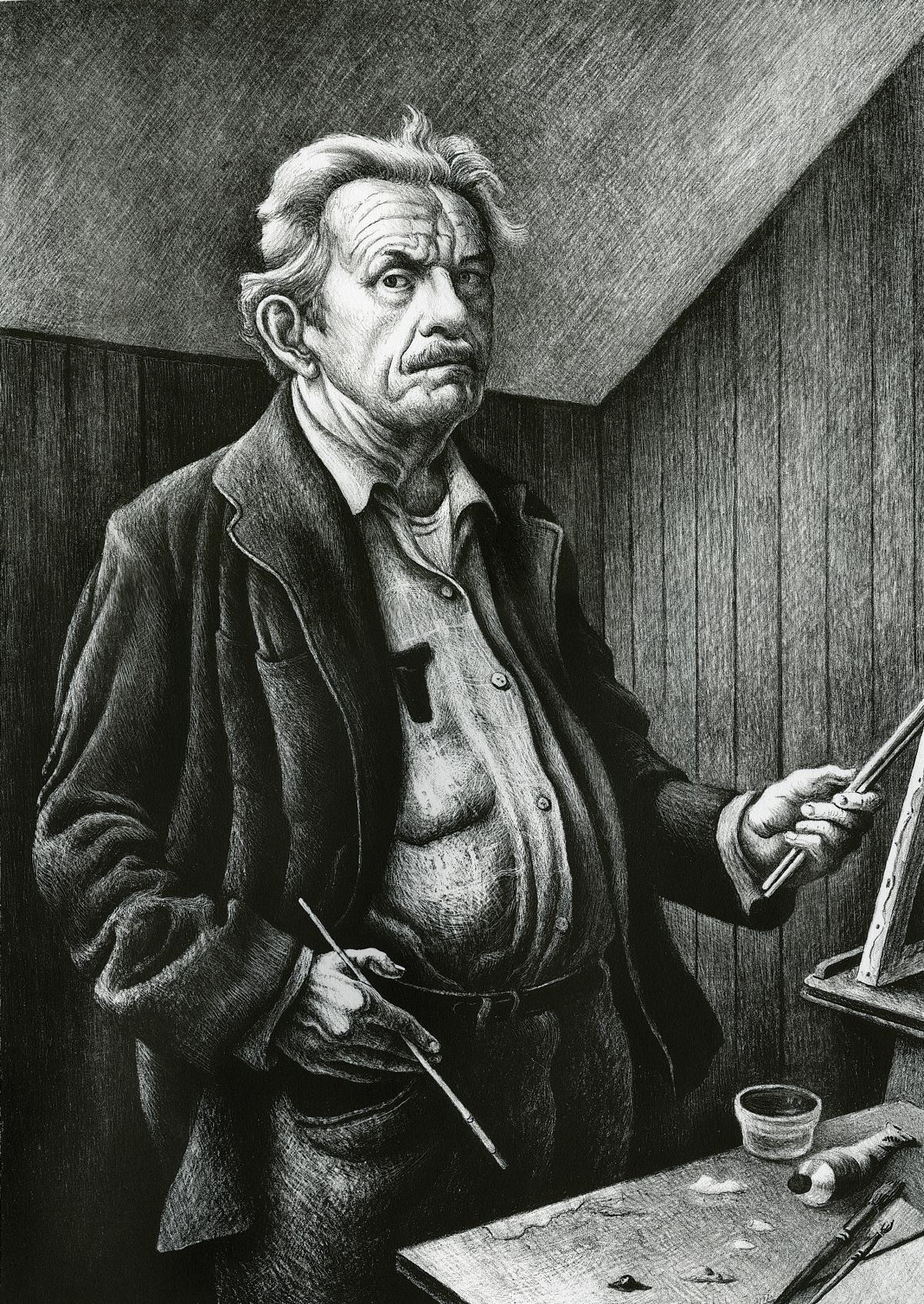

There was probably no better time for Thomas Hart Benton to write his autobiography than in 1937. An Artist in America describes Benton’s life and thoughts, his tumultuous role in the art world, and his plans for further glory, all with the bravado of an artist at the height of his renown. By the mid 1930s, Benton may well have been the most famous artist in America and, for all he squawked about money in his book, probably the best paid.

When he published his life story, Benton was only forty-eight years old. Life was far from over. For another thirty-eight years, all the way into the 1970s, he’d go on living and painting. In that time many things changed in the art world. For one, his own reputation plummeted. And the Modernism of Paris and New York that he had dismissed as “divorced from the common ways of the day” gradually took over the galleries and museums in one wave after another: Abstract Expressionism, Color Field painting, Pop Art, Fluxus, Body Art, Performance Art, Happenings, Minimalism, Post-Minimalism, Conceptualism, Process Art, and on and on. Benton became a historical artifact of what seemed in retrospect to be a humbler, pre-great period in American art, a period that the postwar world felt well rid of.

In the course of those thirty-eight years, An Artist in America was republished twice as new editions, in 1951 and 1968, and in each Benton appended a new last chapter. He used these afterwords to bring readers up to date with his life and work—and to vent.

I. Before

Benton made enemies easily. It was not his art that caused offense—with the possible exception of a reclining nude he exhibited that “had so drawn the male population of the city that a rope had to be thrown around the area where the picture was hung”—but his abrasive personality. Reveling in his hard-drinking, tough-guy persona, Benton frequently attacked the manhood of people with whom he disagreed.

Between the forces of the narrowly conservative and the doctrinaire radical, another influential force thrives in the city. This last is even more completely withdrawn from the temper of America than either of the others. . . . It comes from the concentrated flow of aesthetic-minded homosexuals into the various fields of artistic practice. Aestheticism in its more fragile forms seems always to accompany sexual aberration when that is represented by the simple predominance of feminine characteristics rather than the cultivated vices of bisexualism. In the case of the latter, male sexual buffooneries, accompanied by a more or less open sadism, offset any exaggerated artistic delicacy. But in the homosexual circles of artistic New York there are few who, like the gentleman in the Klondike poem, are ready to jump anything from a steer to a kitchen mechanic. Our New York aberrants are, for the most part, of the gentle feminine type with predilections for the curving wrist and outthrust hip.

Such disparagement was not simply for its own sake. There was a context to these and other nasty comments. Benton was quite aware of how marginalized artists were in American society, and he made it his business to “cowboy up” the image of the artist in America. His book is a travelog of the country, respectfully describing Main Street America in the manner of a politician championing the values of the common people. “These [Mississippi River] people would not,” Benton wrote, “as a rule, trade their wandering life on the water for any certain security. They know that the price of security is loss of freedom.” Part of the point was to show how much of a regular guy the author was to understand all this and get on with so many common types: “What is called society is, of course, like the froth on a glass of beer, of no consequence.” Benton was rough and ready; he could drink with gamblers and parley with wealthy art patrons Albert Barnes and Juliana Force; he had had girlfriends and now a wife; he had been to Europe but knew that America was best. And, dammit, he could paint.

“So, you’re an artist, Shorty?” one of my tormentors asked skeptically.

“Yes, by God! I am,” I said. “And I’m a good one.”

The battle Benton waged with the stereotype of the artist as effete and lazy would be picked up by others. Jackson Pollock’s Wyoming background became an early point in his favor, for example. The issues of the day were the manliness of artists and creating an “American art,” which seem quite dated now, along with the art of that time.

Abstract Expressionism shook the art world like an earthquake in the late 1940s and early fifties and, like an earthquake, it left a number of institutions in shambles. Among the ruins were American Realist (Regionalist and Social Realist) school and the American Abstract Artists group whose members had dominated the galleries and museums in recent years. The Realists especially saw all of their most cherished beliefs about art upended. Art no longer needed to address the common man—the rural laborer in Benton’s or Grant Wood’s paintings, the urban proletariat in Isabel Bishop’s and Reginald Marsh’s art. The new art was concerned with color and formal problems of art.

Arguments over artists' intentions aside, the new art did pose a very practical problem for those Social Realists who still believed in their art and sought to make a living by it. “The big change in the art world damn near buried me,” painter Jack Levine stated, adding that the market for his works shrank considerably for a number of years. Some artists—the most notable being Philip Guston—jumped ship and became Abstractionists. Others slogged on and hoped for a change in the winds of the art world.

Some Social Realists attempted to combine their social concerns with the new emphasis on color as an expressive entity in itself and on the more formal concerns (flatness, the painting surface, lack of illusionism) of the Abstractionists. Isabel Bishop, for instance, showed new interest in the 1950s with movement in a painting as well as spatial relations between figures in a composition, and Ethel Magafan’s pictures became considerably more abstract. Ben Shahn was another painter who refused to eject politics from his work, yet he too began to focus less on specific instances of social or political injustice by the 1950s and more on broader allegorical themes of humanity, with a greater interest in formal, compositional problems of art.

Devoted dealers continued to display the work of the Realists for what was becoming a niche audience. But, for most art enthusiasts, it was as though an entire school of artists had mysteriously died. Books on twentieth-century American art reinforce that impression by highlighting these painters’ work in the 1930s and never again.

II. “After”

The second edition of An Artist in America was published in 1951, two years after Life magazine first wrote about Jackson Pollock, calling him (perhaps sarcastically) “the Greatest Artist in America.” In a new final chapter, entitled “After,” one senses a new bitterness as Benton sought to remind the New York art world, which he had castigated fourteen years before, that he still breathed and still painted. He never once mentions Pollock or his compatriots. Lost is the cockiness of the first edition: “A few people have, at times, expressed a belief that I was not the most desirable kind of fellow to have around. But, all in all, my differences with the home folks, when looked at in perspective, have not amounted to much.” Benton continues, however, to trumpet how famous and successful he is:

For nearly ten years I lived in a generally continuous glare of spotlights. Like movie stars, baseball players and loquacious senators, I was soon a figure recognizable in Pullman cars, hotel lobbies and night clubs. I became a regular public character. I signed my name for armies of autograph hunters. I posed with beauty queens and was entertained by overwhelming ladies like Hildegarde and Joan Bennett. I was continuously photographed and written about by the columnists. I received fan letters by the hundreds. Some of these, not so polite, told me where to get off. People wrote me from Europe, from Germany, Italy, Spain and even from France and from far-off Japan, Indian and Siam.

Updating one’s autobiography, like one’s résumé, is not uncommon, but the overall tone had changed. Benton was now in his early sixties, perhaps more tired and less up for a fight. He described an increasingly prosaic existence: the move from one house to another, the birth of a daughter, his discomfort with nude beaches, an interest in music, how he has less energy than when he was younger. “Working all day and partying all night wasn’t my game anymore,” he wrote. “After” reflects the standard narrowing of the world as one ages and takes stock.

The final ten pages, however, bring Benton to a more urgent story, how the art world—his art world—had been hijacked by Modernists and idealists and purists. He began by apologizing for not mentioning in the first edition two artists, John Steuart Curry and Grant Wood, with whom he had been “linked under the now famous name of Regionalism. We were different in our temperaments and many of our ideas, but we were alike in that we were all in revolt against the unhappy effects which the Armory Show of 1913 had had on American painting. We objected to the new Parisian aesthetic which was more and more turning art away from the living world of active men and women into an academic world of empty pattern.” Citing the “now famous name of Regionalism” was Benton’s first public recognition that he had become someone tied to the past, complete with a coinage. He described the three artists’ objections historically but, as one reads on, it is clear that little has changed to alter his thinking. The chapter ends somberly with a description of how Curry and Wood had become despondent over their falling place in the art world. His attack on contemporary art had become wholly emotional, as though to identify soulless art with the heartless treatment of these warhorses. Visiting Curry shortly before his death, Benton sought to cheer up his former colleague.

“John,” I ventured, “You must feel pretty good now, after all your struggles, to know that you have come to a permanent place in American art. It’s a long way from a Kansas farm to fame like yours.”

“I don’t know about that,” he replied, “maybe I’d have done better to stay on the farm. No one seems interested in my pictures. Nobody thinks I can paint. If I am any good, I lived at the wrong time.”

One can truly date the advent of Modernism in America: February 17th, 1913, when the Armory Show opened at the 69th Regiment Armory in New York City, later traveling to Boston and Chicago, where it was seen by between 250,000 and 300,000 people. This massive exhibit of 1,600 works of art, mostly paintings, presented (for the first time, to most Americans) the work of Bonnard, Braque, Cézanne, Derain, Duchamp, Dufy, Gauguin, Kandinsky, Kirchner, Léger, Matisse, Picabia, Picasso, Redon, Seurat, van Gogh, Vuillard, and a variety of other European Modernists and their American counterparts.

Prior to the Armory Show, the most brisk market for art in America was for European Old Masters of the Renaissance and Baroque periods. Henry Clay Frick, Samuel Kress, Andrew Mellon, J. P. Morgan, and others used their enormous wealth to purchase paintings, sculpture, and drawings by long-dead artists from impoverished European noblemen. In time, most of these works went to public museums, enriching Americans’ understanding of artistic traditions, although this buying gave the impression to artists, other buyers, and the public in general that contemporary American art was of little value. The Armory Show marks the start of contemporary art collecting in America, led by wealthy collectors who created their own museums to show the work of contemporary European and, later on, American artists. The Armory Show also led, within a few years, to the establishment of new art spaces that exhibited both European and American artists. Associating with artists was no longer synonymous with slumming. Rather, being “up” on current trends in art became a sign of sophistication.

The 1930s represented both a setback and an underlying advance for Modernism and American art. The Great Depression turned the country more inward, rejecting artistic experimentation and European models, but that didn’t last.

Abstract Expressionism was a turning point for American culture, providing the United States with its first full-fledged indigenous art movement, and it unleashed a tremendous amount of artistic energy that continues to this day. Whether one likes it or not, the painting and sculpture of the predominant art movements of the postwar era still look fresh and can excite as much controversy now as when they were first exhibited. The same cannot be said about 1930s Regionalist and Social Realist painting or the work many of these artists executed after the Second World War.

Clement Greenberg, the leading critic of the postwar era posited two basic tenets that were adopted by museums and scholars alike. These were, first, that a painting either creates the illusion of three-dimensionality or, in more Modernist works, reflects its inherent flatness and, second, that the subject of modern painting was the paint medium itself and the tensions between the colors and forms. The external world was no longer even a point of reference for art. Greenberg saw recent art history as a general flattening of the painted image, and a growing concern with its medium, beginning with Manet, continuing with Cézanne and Picasso, leading to Abstract Expressionism and, finally, the Color Field painting of Helen Frankenthaler, Kenneth Noland, and Jules Olitski, whom Greenberg called “the greatest painter alive” in 1990. Taking their lead from Greenberg, most modern art curators and museum directors organized their collections along the Manet-Cézanne-Picasso-Pollock axis. Artists not associated with this line of development were afforded less museum space, and viewed implicitly as minor creators.

III. After “After”

Perhaps, by 1968, when the third edition of An Artist in America was published, Benton understood that. A new final chapter was included—entitled “And Still After”— that begins in the manner of “After” with an effort to bring readers up to date on subsequent successes, praise, exhibitions, this and that. He still is ready to argue for the value of his brand of realism (“I still felt that my pictures needed a human content, or something of life that suggested such a content, to be effective in more than a decorative way”), but that is not the point or focus of the new chapter, the last Benton would write. Almost eighty years old, he began to recast himself: His legacy was not just the artwork he left behind but his influence, particularly on Jackson Pollock, whose art exactly represents the type of Modernism Benton had been railing against for decades. “It is well known that Jackson Pollock began his first serious art studies under my guidance,” he began. “It is less well known that he was also, for nearly ten years, on very close friendly terms with me.”

Subsequent art historians have pointed up the strong influence that Benton’s rounded forms and manner of painting had on the early work of Pollock, as well as the effect of the older artist’s Americanism on how the future Abstract Expressionist leader would see his own role. Benton makes little allowance for a talent he could not understand: “Although, as I have said, Jack’s talents seemed of a most minimal order, I sensed he was some kind of artist. I had learned anyhow that great talents were not the most essential requirements for artistic success.”

Still, Benton hoped to smuggle his own reputation into the juggernaut that was Pollock and the New York School and Modernism in general. Benton described Pollock as a student and a house guest at Martha’s Vineyard, once needing to be bailed out of jail following a drunk-and-disorderly arrest. The anecdotes do not obscure what Benton clearly hopes to identify as an artistic debt. “A good deal has been said lately about Jack Pollock’s indebtedness to me,” he noted. “Even after I had castigated his innovations and he had replied by saying I had been of value to him only as someone to react against, he kept in personal touch with me and with Rita.” Two famously cantankerous artists were able to make peace with one another, and that bond with youth brings Benton into the present: “With all this deep-reaching personal stuff in memory, I could not but feel a considerable satisfaction in Jack’s final success.”

In his own way and on his own terms, Benton identified what his future legacy would be and summarized it in his now twice-expanded autobiography. And with his public acknowledgment of Pollock’s success, he closed the book on his own work with a becoming note of reconciliation. For Social Realist and Regionalist artists and for those who subsequently replaced them, there was an important lesson here: The art world holds open a window of opportunity for only a short period of time. Art is about universal concerns of life, the world one inhabits, and the ability to express oneself, but life, the world, and the meaning of self-expression change in increasingly brief spans of time. Since the Impressionists, no one style of art has dominated for longer than a decade, and artists have found that they must seize their moments and tenaciously hold onto them or risk being passed by.

There are many autobiographies of writers, athletes, politicians, entertainers, business executives, and others who want to tell the world how miserable their lives have been, but relatively few by fine artists. There is none by the major artists of the twentieth century, such as Picasso, Matisse, Marcel Duchamp, Miró, Pollock, de Kooning, Rothko, Johns, Rauschenberg, and Andy Warhol’s Philosophy is largely filled with aphorisms. So many questions that artists might want to know: How did the Big Time Artist support himself before his work began to sell?, How did the Portraitist come to meet the collectors and dealers who were to buy her work and support her career?, What kinds of anxieties did the Name Artist feel when their art was not selling or when criticism was negative or when other artists were receiving attention? The answers are unknown to us, because few artists write their own stories and their biographers treat these subjects as mere anecdote.

Benton probably did not intend to reveal so much about the life of an artist, as opposed to his own life and art, but he said a great deal. Had he not periodically updated his Artist in America, there would be little of value in the book to anyone other than devotees of the artist and the few scholars interested in American Regionalism. Instead, Benton went public with his feelings about being ignored by museums and collectors and viewed as irrelevant by critics and by artists whose newer work he didn’t understand or like. All artists who achieve major recognition in their careers, and many more who don’t reach such heights, will understand the torment of his last thirty-eight years. What we see in these added chapters is an artist grappling with his times and, ultimately, seeing himself anew through the eyes of others. It is a remarkable thing that Benton has done for us, a final lesson from the old teacher.