In the aftermath of the Senate hearings to consider the president’s nominee to become the next U.S. Supreme Court justice, it’s hard to remember that the process wasn’t always like this. There weren’t always weeks of media coverage, and there weren’t always hearings. Nor did individual senators spend hours calling witnesses, making statements, or cross examining the nominee. In fact, the first nominee didn’t testify before the Senate Judiciary Committee until 1925, when Harlan Stone proposed an appearance to answer questions about his ties to Wall Street. It would be another fourteen years and five justices until nominee Felix Frankfurter appeared before the committee to address rumors that he was secretly a Communist. Starting with John Harlan in 1955, all nominees appeared before the Senate Judiciary Committee. Southern senators, unhappy with the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision, wanted the opportunity to question nominees about their judicial philosophy. Even so, subsequent hearings lasted three days at most.

The short-and-sweet approach became a thing of the past in the late sixties, as the vetting of Abe Fortas, Homer Thornberry, Clement Haynsworth, and G. Harrold Carswell turned into extended brawls. At issue was the legacy of the Warren Court. But the changes in political process were also important, as they proved long-lasting and transformed the way the Senate provides “advice and consent” to the president on Supreme Court nominees.

At the end of June 1968, President Lyndon Johnson announced that Chief Justice Earl Warren intended to retire. Warren had presided over the Court since 1953. During his tenure, the Court handed down a series of rulings that expanded civil liberties and protected the rights of individuals. Brown v. Board of Education and subsequent civil rights rulings uprooted Jim Crow laws in the South and challenged long-standing racial mores. The Court also expanded First Amendment rights, rolling back laws that barred Communists from jobs and targeted pornography. Prayer and Bible reading were also banned in public schools. The rights of the accused were expanded as well, including the 1966 Miranda v. Arizona decision, which required police officers to inform criminal suspects of their Constitutional rights prior to questioning.

The news of Warren’s retirement came as a relief to Southerners, states’ rights advocates, social conservatives, and law-and-order proponents. In their eyes, the Warren Court had corroded the fabric of American society.

Warren’s retirement, however, came with strings: His resignation would not become effective until "such time as a successor is qualified." To replace Warren, Johnson wanted to elevate Associate Justice Abe Fortas to chief justice and appoint Homer Thornberry to fill the empty associate justice chair. Both men were liberal and would carry on the work of the Warren Court.

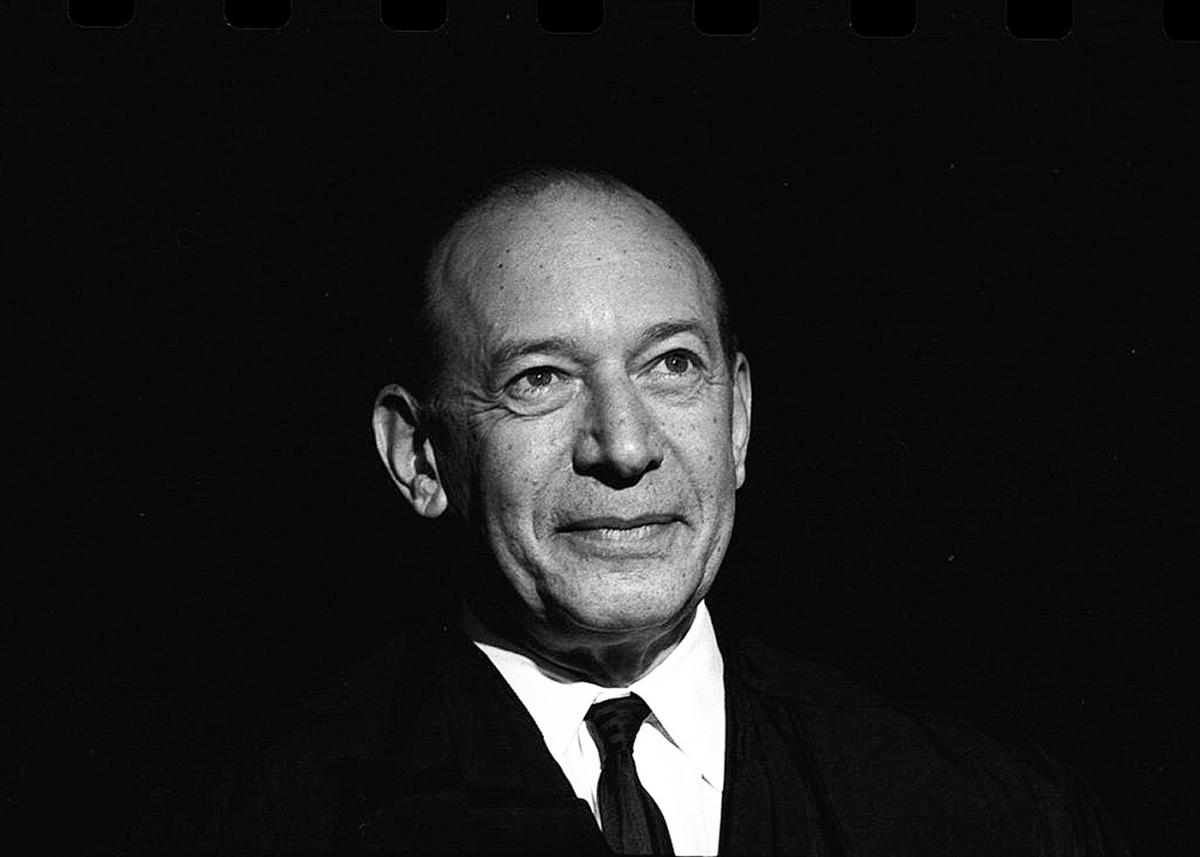

Fortas had served on the Supreme Court since 1965 when he replaced Arthur Goldberg as the Court’s only Jewish justice. Born and raised in Memphis, Fortas put himself through Southwestern College (now Rhodes College) by playing the violin at school dances. A stellar turn at Yale Law earned him an appointment as assistant professor upon graduation in 1933. Four years later, Fortas headed to Washington to work for the Roosevelt administration, becoming undersecretary of the Interior in 1942. In 1948, he co-founded one of Washington’s leading law firms, Arnold, Fortas & Porter (now Arnold & Porter).

Thornberry was a dear friend of Johnson’s from their early days in Texas politics. The product of a dirt-poor upbringing by deaf parents, Thornberry worked his way through the University of Texas and its law school as a deputy sheriff. While still in law school, he was elected to the Texas legislature. A stint as district attorney followed, along with service in naval intelligence in World War II. The friendship continued in Washington, when both men were elected to Congress in 1948, Johnson as a senator and Thornberry as a representative. In 1963, Thornberry left Congress to become a federal district judge and was named by Johnson to the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals two years later.

Howls of outrage rose from Capitol Hill about Chief Justice Warren’s retirement, which shocked Johnson. Senators on both sides of the aisle bristled at his conditions, regarding them as an affront to the chamber’s Constitutional right to advise the president on nominees. Republicans howled the loudest. They believed that Johnson and Warren were conspiring to prevent the next president—which, if the polls held, would be Republican—from picking a new chief justice. Robert Griffin, an ambitious junior senator from Michigan, circulated a petition demanding Johnson be denied the right to appoint anyone to the bench for the remainder of his term. Nineteen Republican senators signed on. Georgia Democrat Richard Russell privately told Griffin that while he and other Southern Democrats would not make any public statements against Fortas, they would vote against him when the time came.

The Republicans also harped on what Griffin called “cronyism at its worst.” While Johnson had a long history with both Fortas and Thornberry, his friendship with Fortas, in particular, became an issue. It had been Fortas who successfully represented Johnson in a dispute over his victory in the 1948 Texas Democratic primary; Fortas who recommended that Johnson create the Warren Commission to investigate the Kennedy assassination; and Fortas who served as Johnson’s secret envoy to the exile government of the Dominican Republic. Fortas continued to serve as an adviser after becoming associate justice, raising questions about the separation of powers. As Time magazine reported, “No one outside knows accurately how many times Fortas has come through the back door of the White House but any figure would probably be too low.”

By the time the Senate Judiciary Committee opened hearings on July 11, the anti-Fortas forces were ready to do battle. Griffin had a major ally in Committee Chair James Eastland. A Mississippi Democrat and white supremacist, Eastland believed that the Brown decision had destroyed the Constitution. Also on the attack were North Carolina Democrat Sam Ervin, a strict Constitutionalist who had served as an associate justice on the North Carolina Supreme Court; South Carolina’s Strom Thurmond, an ardent proponent of states’ rights who had switched his allegiance from Democrat to Republican in 1964; and Roman Hruska, a Republican from Nebraska. The pro-Fortas camp consisted of Illinois Republican Everett Dirksen, the Senate minority leader and one of the authors of the 1964 Civil Rights Act; Michigan Democrat Philip Hart, a former lawyer who was known as the “conscience of the Senate”; Massachusetts Democrat Ted Kennedy; and Indiana Democrat Birch Bayh.

Rather than beginning with the traditional “meet the nominee” segment, the hearings opened with a debate over whether a Court vacancy even existed. To settle the issue, the committee subpoenaed Attorney General Ramsey Clark, who assured the senators that there was in fact a vacancy. Next the committee called four witnesses who charged Fortas with being soft on communism. Kent Courtney, national chairman of the Conservative Society of America, charged that “Justice Fortas ruled with the Communists, with Communist individuals on behalf of the Communist conspiracy, and voted against the Congress of the United States.”

On day three, the committee finally got around to hearing from Fortas. As part of his introduction, Senator Albert Gore, Sr., of Tennessee questioned whether Fortas needed to testify, noting that when Edward White was elevated from associate to chief justice in 1910, he didn’t testify. Neither did Harlan Stone in 1941. Gore also challenged the appropriateness of asking a justice to explain his rulings rather than letting the record speak for itself. After all, senators wouldn’t be asked to justify their votes. The precedents failed to sway Eastland and he called Fortas as a witness.

In his opening statement, Fortas directly addressed his role as adviser to Johnson: “Since I have been a justice, the president of the United States has never, directly or indirectly, approximately or remotely, talked to me about anything before the Court or that might come before the Court. I want to make that absolutely clear.” Yes, he sometimes acted as a sounding board, but he didn’t regard his role as unusual, as other justices had done the same. Chief Justice John Jay counseled Washington. Roger Taney did the same for Jackson, as did David Davis for Lincoln. Chief Justice William Howard Taft advised Harding, Coolidge, and Hoover.

Fortas then endured four straight days of questioning about his legal career and philosophy. Ervin, the self-described “country lawyer,” monopolized two of those days as he dissected opinions Fortas joined as part of the Warren Court. Despite repeated requests, Fortas refused to comment on specific rulings, insisting that Court opinions spoke for themselves. He wasn’t the first nominee to take such a stance. Former judges Felix Frankfurter and Thurgood Marshall had done so, as well as senator-turned-justice Sherman Minton. When asked if he was an “original meaning” or a “living document” man, Fortas equivocated. When asked numerous “suppose Congress passes a law” questions, he declined to speculate. The closest Fortas came to discussing politics was when he was asked to what extent the Court should attempt to bring about social or economic change. His answer: “Zero, absolutely zero.”

Fortas’s reticence infuriated his critics. Thurmond demanded to know why Fortas could give lectures and talk policy with the president but couldn’t discuss his rulings with the committee. Fortas’s answer was simple: to preserve the separation of powers. No judges shall be held to answer before any other branch of the government for their views.

After six days, Eastland closed the hearings, then reopened them for another three. The committee had been so fixated on Fortas that it forgot about Thornberry. Like Fortas, Thornberry insisted on standing on his opinions, prompting Ervin to suggest that a nominee’s refusal to discuss former opinions had created a new right not found in the Constitution.

Eastland didn’t corral a vote before Congress’s summer recess. Unfortunately for Fortas and Thornberry, the delay helped seal their fate. During August, both parties held conventions to pick their tickets for the upcoming presidential election. In Miami, strong-arming of the Southern delegations by Thurmond and political operative Harry Dent helped a faltering Richard Nixon secure the Republican nomination. In Chicago, the Democrats picked Minnesota son Hubert Humphrey, as protests and violence engulfed the convention and the city. Nixon and the Republicans went into September with a post-convention bump in the polls, strengthening the resolve of Fortas’s opponents.

When Congress returned to session, Eastland opened the hearings for another two days. Thurmond and Griffin had planned to focus on Fortas’s record on pornography and his friendship with Johnson, but an anonymous phone call pointed them in the direction of a nine-week summer seminar Fortas had taught for American University Law School. Fortas received $15,000 for the seminar, roughly 40 percent of his regular salary. Previous teachers had been paid $2,000. B. J. Tennery, the dean of the law school, explained to the committee that Fortas was also being compensated for developing teaching materials. Private donations solicited by Paul Porter, Fortas’s old law partner, paid for his salary. The donors consisted of two directors for Braniff Airways, two department store magnets, along with the chairman of the New York Stock Exchange. Fortas now had a possible conflict-of-interest problem, since it was inevitable that issues important to those entities would come before the Court. After a lurid examination of Fortas’s record on pornography by Thurmond, which included a screening of two explicit films deemed to be free speech by the Warren Court, the hearings were gaveled to a close.

The hearings had run for eleven days. The hearing three years earlier to confirm Fortas as associate justice had run for three hours.

At the beginning of October, Fortas’s nomination went to the full Senate for a vote. For four days straight, senators defended or lambasted Fortas until a cloture petition to end the debate was introduced. The vote, 45-43 in favor of cloture, was a harbinger of Fortas’s confirmation prospects. It was fourteen votes short of the two-thirds majority needed to end the debate and compel a vote on the nomination. Fortas asked Johnson to withdraw his name, a move that also spelled the end of Thornberry’s nomination as well.

Elected the next president of the United States in November 1968, Nixon feared that Johnson might try to make a lame duck appointment. Remaking the Supreme Court had been a battle cry of his campaign, and he had no intention of losing out on the chance to appoint a new chief justice. To foil Johnson, Nixon asked Warren to stay on through the Court’s spring term. In May 1969, Nixon picked Warren Earl Burger to be the next chief justice. Appointed by Eisenhower to preside over the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, the conservative Burger had a sterling reputation. Republicans and Democrats volunteered to testify on his behalf, as did six past presidents of the American Bar Association. His confirmation hearing lasted one hour and forty-five minutes.

Nixon was soon given the chance to make another appointment. The Fortas nomination hearings convinced White House and Senate Republicans that he was vulnerable either to forced resignation or impeachment. In May 1969, Life magazine cataloged Fortas’s tangled relations with financier Louis Wolfson, who had been convicted of stock manipulation. Further investigation by the Justice Department revealed Fortas had entered into a $20,000-a-year lifetime arrangement to advise the Wolfson Family Foundation. As David Kyvig recounts in his NEH-funded book The Age of Impeachment, Attorney General John Mitchell, acting on orders from the White House, threatened to indict Fortas for his involvement with Wolfson if he would not resign from the Court. Meanwhile, Griffin started telling reporters that Fortas should resign in order to avoid impeachment.

The appearance of impropriety overwhelmed the fact Fortas had done nothing ethically wrong. There was no evidence to support the criminal charges either. Nevertheless, Fortas decided to resign. As he told Washington Post editor Benjamin Bradlee, “If I stayed on the Court, there would be this constitutional confrontation that would go on for months. Hell, I feel there wasn’t any choice for a man of conscience.”

Kyvig notes that the campaign against Fortas, not only set a new precedent for the review of Supreme Court nominees, but it also revived impeachment as a political tool. “Impeachment stood revealed as a working weapon whose mere threat could achieve the departure of compromised federal officials and advance other political agendas.” The irony is that Nixon and his vice president, Spiro Agnew, would both face impeachment proceedings, victims of a weapon the White House helped revitalize.

The vacant Fortas seat provided Nixon with the opportunity to settle a campaign debt. To win the Republican nomination, Nixon had prostrated himself to Southern Republicans. In exchange for delivering delegates, he swore to Thurmond and other Southern congressmen that he would appoint a strict Constitutionalist and a Southerner to the Supreme Court.

Nixon announced Clement Haynsworth as his pick to succeed Fortas in August 1969. A native of Greenville, South Carolina, Haynsworth attended Furman College, which was founded by his great-great-grandfather, then went on to Harvard Law. After a successful career as part of his family’s firm, he was appointed to the bench by Eisenhower in 1957, becoming chief justice of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit seven years later at the age of fifty-two. His manners and his bearing bore all the hallmarks of a Southern gentleman. Widely respected by his colleagues for his scholarly opinions, Haynsworth was known, at least to his friends, also to be a prankster as well as a devoted gardener of prizewinning camellias.

Within days of the announcement, opponents began to attack Haynsworth’s record on civil rights and labor. A little digging by the press also revealed that Haynsworth had failed to recuse himself from several cases where he had a financial interest. The most damning involved the closure of Darlington Manufacturing Company after the Textile Workers Union of America won the right to represent its employees. The National Labor Relations Board ruled the closing of the textile mill an unfair labor practice. On appeal, Haynsworth joined two other judges in ruling against the NLRB. While the case was under review, Haynsworth held stock in Deering Millkin, Darlington’s parent company, which he subsequently sold for $455,000.

Given Haynsworth’s distinguished career, the White House thought that he would be another slamdunk. Instead, Haynsworth was being subjected to the same level of scrutiny that had been applied to Fortas and wasn’t coming out the better for it. Haynsworth supporters—coincidentally the same bipartisan group that opposed Fortas—now had to use the hearings to defend their candidate against the very tactics they had inaugurated.

When the confirmation hearings opened on September 16, the first item on the agenda was whether to even hold the hearings, given the conflict-of-interest charges being leveled at Haynsworth. Both Eastland and Hruska declared there to be no conflict of interest, a position backed by a letter from Assistant Attorney General William Rehnquist. The hearings were a go.

Over the next eight days, the pro-Haynsworth faction tried to downplay the ethics issue and minimize discussion of Haynsworth’s civil rights record. Witnesses testified as to Haynsworth’s scholarship and fine legal mind. Time was given to labor unions, who objected to his record, but their criticisms carried little weight. Direct questioning of Haynsworth by the senators was anemic in comparison to the treatment Fortas received. There was no Ervin acting as judicial pit bull. Like Fortas, Haynsworth refused to discuss any of his rulings, despite requests by the senators to elaborate on points of law. Unlike Fortas, he wasn’t lambasted for declining to answer.

By day six, the pro-Haynsworth faction couldn’t keep the civil rights issue in check. That it had taken that long to hear from critics was no accident. Roy Wilkins, the executive director of the NAACP, was dismissed as a witness on the second day of the hearings, despite having informed the committee it was the last day he could testify because of an upcoming month-long trip to Europe. He was replaced with a Haynsworth advocate. The committee, however, couldn’t refuse to hear from a fellow congressman. New York Representative William Ryan delivered a blistering critique, charging Haynsworth with casting crucial votes against implementing and speeding the pace of desegregation. As a footnote, Ryan mentioned that Haynsworth was anti-labor, an observation that Ervin seized on to try to steer the hearing away from civil rights. Unsuccessful in his gambit, Ervin launched into a diatribe questioning why the federal government hadn’t ordered the desegregation of schools in Harlem.

Clarence Mitchell and Joseph Rauh of the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights testified about Haynsworth’s pattern of obstructionism on civil rights as well. When they finished their statements, Hruska asked how much longer they intended to testify, as the committee had other witnesses to call. Mitchell politely noted that the issue of civil rights deserved a fair hearing, telling Hruska, “You cannot spend too much time in considering it.” Hruska disagreed. “Oh, yes, too much time can be consumed,” he said. After Rauh and Mitchell were dismissed, following extensive questioning by the committee, Hruska offered into record a memo defending Haynsworth’s civil rights record.

The hearings, which the White House and Haynsworth supporters believed would be pro forma, had turned into another slugfest. Haynsworth’s nomination made it out of the committee only to be rejected by the Senate: 45 in favor, 55 against.

Nixon was livid. The Democratic-controlled Senate had decided to seek revenge for Fortas with his nominee—or at least that’s what he thought. The vote breakdown was more complicated. The Democrats controlled the Senate 57-43. Seventeen Republicans voted against Haynsworth; nineteen Democrats had voted for him. Those who crossed party lines did so, it generally seemed, because of Haynsworth’s ethics or his civil rights record. Even Griffin voted against Haynsworth. Given the ethics issues, doing otherwise would have made him a hypocrite.

The Nixon White House learned two lessons from the Haynsworth hearings: Make sure the nominee’s financial dealings were sound and don’t give the opposition time to comb through the nominee’s record.

On January 19, 1970, Nixon announced that he was nominating G. Harrold Carswell for the seat Fortas had resigned. A native of Georgia, Carswell ventured to Duke University for college, followed by service as a Navy lieutenant in the Pacific during World War II, then on to Mercer University Law School. After a failed bid as a Democrat for a seat in the Georgia legislature, Carswell moved to Tallahassee, Florida, and entered into private practice. He came to the attention of the Republicans when he squared off against an Adlai Stevenson supporter in favor of Eisenhower during a radio debate. When the Republicans took office in 1953, Carswell was named a U.S. Attorney. A switch in party helped Carswell garner an appointment as a federal district judge in 1958. Six months before his nomination to the Supreme Court, Nixon had elevated him to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit.

Eastland agreed to open the hearings eight days after Nixon made the announcement. But it only took two days for the press to uncover a speech delivered by Carswell during his 1948 legislative campaign. “I am a Southerner by ancestry, birth, training, inclination, belief, and practice. I believe that segregation of the races is proper and the only practical and correct way of life in our states,” he declared. The White House tried to suggest that the words were merely attributed to Carswell, but the speech had been printed in the Irwinton Bulletin, a weekly newspaper run by Carswell while at Duke. Carswell also appeared to have been a charter member of a scheme to turn a public golf course in Tallahassee into a whites-only country club.

The first morning of the hearings was devoted to diffusing the charge that Carswell was racist. Asked by Hruska about the speech, Carswell said: “I state now as fully and completely as I possibly can, that those words themselves are obnoxious and abhorrent to me. I am not a racist. I have no notions, secretive, open, or otherwise, of racial superiority. That is an insulting term in itself and I reject it out of hand.” He regarded the speech as “something out of the disembodied past.” Carswell’s repudiation of his words prompted questions about what made him change his mind. “The course of the twenty-two years of history,” he told the committee. “There have been vast changes, not only in my thinking, but in the country and in the South particularly. There is a good more that needs to be done.”

A series of witnesses testified about Carswell’s role in the country club scheme, leaving the situation murkier than when the hearings began. An examination of Carswell’s civil rights record revealed a pattern of obstructionist tactics. William van Alstyne, a Duke law professor, testified that five of Carswell's rulings in desegregation cases had been reversed on appeal. Two examples are illustrative. In Augustus v. Board of Public Instruction of Escambia County, Florida, the Court of Appeals unanimously rejected the school desegregation plan approved by Carswell and required the school board to take further action. In Due v. Tallahassee Theatres, Inc., an action against theater managers, city officials, and the county sheriff alleging a conspiracy to enforce segregation, Carswell ruled the complaint inadequate. The Court of Appeals reversed Carswell, calling it a classic example of conspiracy to deprive the black plaintiffs of their Constitutional rights.

Some of the most compelling testimony came from three witnesses who had worked as volunteer lawyers in Florida during the 1964 voter registration drive. They described how Carswell routinely interfered in cases involving voting rights activists, going so far as to collude with city attorneys and local sheriffs to use procedural maneuvers to deny habeas corpus hearings. In one case, nine clergymen were denied a hearing and given reduced sentences for time served, leaving them with permanent criminal records. Norman Knopf, who volunteered with the Law Students Civil Rights Research Council, testified that Carswell berated northern lawyers for coming to Florida and “arousing the local people.” Leroy Clark, who directed the NAACP’s legal division for Florida, called Carswell’s behavior toward black attorneys “insulting and hostile.”

Concern about Carswell’s mediocre skill as a jurist grew as well. Forty percent of his rulings had been overturned on appeal, putting him, according to one assessment, in the bottom 10 percent when compared with his fellow judges. His opinions were short and said to be poorly researched. He cited half the number of cases as his fellow judges. As Louis Pollak, dean of Yale Law School, told the committee: “There is nothing in these opinions that suggests more than at very best a level of modest competence, no more than that.” Griffin found criticism of Carswell’s judicial record astonishing. “Frankly, I must register my disagreement with those who criticize your opinions by comparing them to a plumber's manual or by indicating concern because your opinions are concise and to the point.” Hruska suggested that critics were focusing on Carswell’s scholarship because they didn’t like that he was a Southerner. In an unguarded moment, he would famously tell reporters, “Well, even if he were mediocre, there are a lot of mediocre judges and people and lawyers. They are entitled to a little representation, aren’t they, and a little chance?”

The hearings were closed, after five days, when it became clear that no amount of pro-Carswell witnesses could undo the testimony given about his civil rights record. As Rauh told the committee, “He is Judge Haynsworth with a bitterness and a meanness that Judge Haynsworth never had. A Senate that would not confirm Judge Haynsworth cannot confirm Judge Carswell.” Carwsell became the third nominee rejected in three years when the Senate voted on his confirmation: 45 in favor, 51 against.

Not since Grover Cleveland had the Senate rejected two of the president’s Supreme Court nominees. Nixon issued a rather angry statement. “Judge Carswell, and before him, Judge Haynsworth, have been submitted to vicious assaults on their intelligence, on their honesty, and on their character. They have been falsely charged with being racists. But when you strip away all the hypocrisy, the real reason for their rejection was their legal philosophy, a philosophy that I share, of strict construction of the Constitution, and also the accident of their birth, the fact that they were born in the South. . . . I understand the bitter feelings of millions of Americans who live in the South about the act of regional discrimination that took place in the Senate yesterday.”

Charging the Senate with prejudice against the South was a convenient way for Nixon to explain the defeat of his two nominees. The reality was far more complex. The Senate rejected Haynsworth and Carswell, the Congressional record makes clear, because of their ethical problems and civil rights records. They were also victims of the tactics their supporters used on Fortas. The dissection of Fortas made possible the dissection of Haynsworth and Carswell.

The hearings also created a template for dealing with a controversial nominee that extended beyond the Nixon administration. Critics of Robert Bork, nominated by Ronald Reagan in 1987, deployed the same tactics used against Fortas. The Senate Judiciary Committee questioned Bork for a record five days—one day longer than Fortas—and heard from more than one hundred witnesses. While Bork’s nomination failed, it generated a new word: to bork someone is to deny them a judicial appointment.

Nixon abandoned his quest to appoint a Southerner and nominated Harry Blackmun, a conservative appellate judge from Minnesota, in April 1970. Blackmun’s hearing lasted three hours and five minutes. The Senate confirmed his appointment 94-0. As for the men whose defeats served to change the nature of the nomination hearings, Fortas started his own law firm, Fortas and Koven. Thornberry served as Fifth Circuit judge until one month before his death at age eighty-six, acquiring a reputation as an advocate for racial justice. Haynsworth continued to serve as chief justice for the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit until he retired in 1981. Carswell resigned from the bench and threw his hat into the Florida Senate race, with a campaign cry of “This time the people decide!” He was defeated in the primary and entered private practice.