In January Bruce Cole resigned the chairmanship of NEH. Before leaving, he sat for an interview with HUMANITIES magazine.

HUMANITIES: Let’s start with a follow-up question from our last interview with you. Do you still ride a motorcycle?

BRUCE COLE: I have a motorcycle.

HUMANITIES: You have a motorcycle.

COLE: It’s a Suzuki 750 single and it’s gathering dust right now, hasn’t been ridden for a while.

HUMANITIES: Are you one of those people who insist on riding without a helmet?

COLE: No, given the way that I drive the motorcycle, a helmet is advisable.

HUMANITIES: Where were you born?

COLE: Cleveland.

HUMANITIES: When did you decide to study art history? In college?

COLE: Yes. I had a great teacher, Marvin Becker, a historian of Renaissance Florence. He was a fascinating lecturer and very passionate about his subject. I got the bug from him. I came into that class not knowing anything about the Renaissance and left deeply interested in it. From there, my path led to Renaissance art.

I was also inspired by a course I took on Western Civ. I remember looking at this wonderful picture of the meeting between St. Anthony and St. Paul. It’s over in the National Gallery, and I go over and look at it every once in a while. Somehow looking at that picture was an epiphany for me. It set me on my path.

I couldn’t quite make up my mind whether I was going to study art history or history. So I had a double major.

HUMANITIES: At what school did you study?

COLE: Case Western Reserve in Cleveland. Of course, Cleveland had and still has a great museum and a very fine collection of Italian Renaissance art. During my undergraduate years, I spent a lot of time in the museum and doing a lot of firsthand looking, which was a very good way to get started.

HUMANITIES: Then you specialized in fourteenth-century Renaissance?

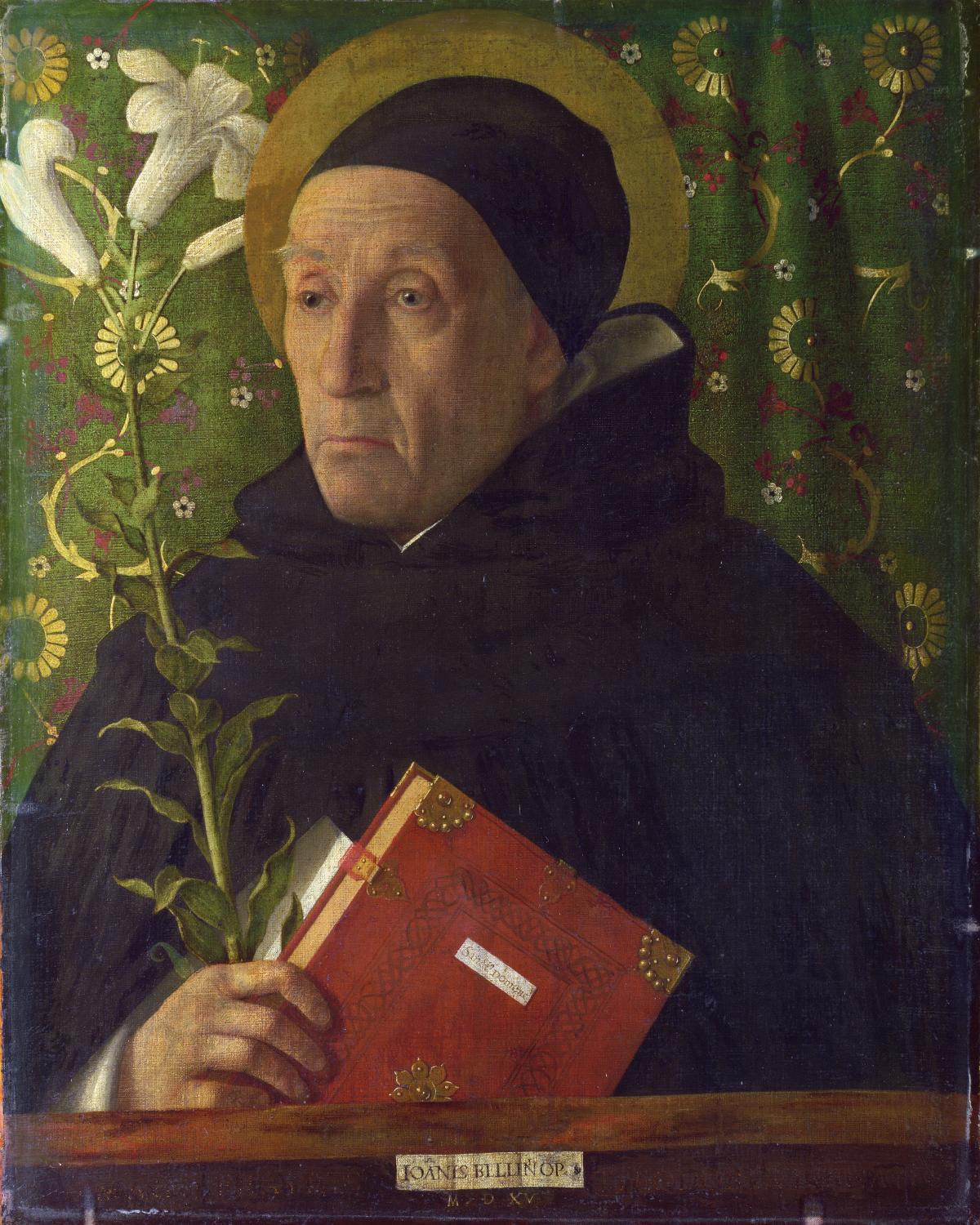

COLE: Yes. My dissertation was on a very obscure fourteenth-century painter, Agnolo Gaddi, who remains obscure. But when I was writing on him, I thought he was the most important artist of the Renaissance and I then sort of worked my way forward. I did some books on the fifteenth-century artists and then the last art history book on the Renaissance I did was on Titian, a sixteenth-century artist.

HUMANITIES: I don’t know if I told you this, but I’m a big fan of your book The Renaissance Artist at Work, especially the first chapter, which describes the working life of a Renaissance artist, and it’s a blue-collar life.

COLE: I wrote that book because art historians devote a lot of time to figuring out the chronology of painters or the iconography of painters or the more highfalutin aspects of art history, but few people are interested in how things are made. What people have a fascination for is the material aspect of art, but you really can’t understand how anything gets constructed or why it looks like it does unless you understand how the whole thing came into being.

HUMANITIES: The other thing I liked about it was the emphasis on art as work and how people ended up becoming artists. You describe these almost clannish social organizations of fathers and sons and brothers and cousins working in the same shop, and they’d all work together. It’s like one of these families in which because the father does carpentry, so does the son, and so does his son.

COLE: Right.

HUMANITIES: It presents the artist rather differently from the modern conception. The artist is not some lofty figure, but a worker.

COLE: We have this 21st-century notion, which comes from the nineteenth century, of the artist that we then project onto the past: the artist as a loner, a bohemian, somebody who lives in a garret, devotes his life to art, has very romantic ideas about creativity, which the Renaissance didn’t have. Art was a trade. Artists had shops just like the butcher, baker, and candlestick maker, and the art trade was really indistinguishable from other trades. Most people got into these shops not because they showed talent, but because they were related to somebody, or it was their father’s or their brother’s or their uncle’s shop.

People of the Renaissance had this idea that artists are made, not born. We have the opposite idea, that ours are born, and that unless you have this intrinsic artistic talent, you can’t be an artist.

HUMANITIES: We should also talk about the modern scholar at work. The caricature of the contemporary scholar is of someone burrowing into an incredibly specialized body of knowledge and analyzing it and writing about it only for other specialists. But you, as a scholar, sought to move and work beyond that. When did you decide, and how did you come to that conclusion, that you should not be writing simply for other scholars?

COLE: I published my dissertation with Oxford University Press and it was a modified dissertation, replete with many, many footnotes and appendices, Latin documents, and the like. It was a full-blown scholarly production, but I was curiously dissatisfied with the experience because I knew it would only be read by ten people and immediately five of them wouldn’t like it. And I thought, well, I’m very enthusiastic about this and I’ve put a great deal of work into understanding the Renaissance and what I really want to do is communicate. I want to have as many people as possible share my enthusiasm. So I decided this was not the right format.

I don’t want to disparage scholarly monographs. They do add to the stock of our knowledge, but writing them wasn’t for me.

So I started to write for a more general audience, people who were interested in the Renaissance and wanted to know more about it but not on an overly scholarly level. So that’s where I aimed the rest of my books. And this kind of writing was much, much more satisfying for me because the catchment of readers was much greater. I think one of the great aims of art history is to try to get people to go and look at the original and, so, that’s another aim of mine.

HUMANITIES: How has this desire to address a larger audience affected your leadership of the Endowment?

COLE: Well, the Endowment supports a lot of scholarship, and it supports a lot of highly specialized scholarship, like the Comprehensive Aramaic Lexicon, which is online and is one of my favorite projects, and very important because much flows from that. But the Endowment is funded by taxpayers and it has a duty not only to support scholars but also to try to bring knowledge of the humanities to all corners of this country. My experience writing for a wider non-scholarly public helped me to see and understand that the larger public mission of the Endowment is to bring humanities to all our citizens, because the humanities are beneficial. They give us a perspective by telling us where we’ve come from, and they furnish a compass to the future and help make us better citizens. So, I take the Endowment’s public mission very seriously. Much of this work is, of course, built on scholarship, but then goes beyond it.

HUMANITIES: I’m told that you’re a believer in what is sometimes called the “great man theory of history.” Is that true, accurate?

COLE: Well, I think there are also great women who have made decisive contributions to history. Also, I think it’s important to study and to look at the lives of all sorts of people. There are a lot of people who were neglected prior to the twentieth century, women and minorities especially, who played an important role in the development of history, and their lives should be studied. What I want to see is a balance between that kind of bottum-up history and the more traditional top-down history. I don’t want to see the pendulum shift so far that we forget there are great figures who can change history.

When I walk to work, I pass Blair House, where Robert E. Lee was offered command of the Union Army, which he didn’t take because he wanted to go back to

serve Virginia. Just think about that.

So, I don’t think that history is just these vast impersonal forces that carry people along. I don’t think it’s just about economics or any particular thing, but I

think greatness, and evil as well, are shown by the fact that people can make a difference in the way things turn out.

HUMANITIES: You’re a big reader of biographies.

COLE: That is true.

HUMANITIES: And I know you’re a big fan of David McCullough. Who are some other biographers and some biographies you especially like?

COLE: I like historians who speak to a large audience. Another of my favorites is Gibbon. He is, for me, the great writer of history, not only because of the scope of what he did but also because of his use of language and his ability to use irony and words to be evocative.

What I also like about Gibbon and McCullough is their ability to synthesize. Robert Caro is another biographer that I particularly like, his books on Lyndon Baines Johnson especially. I think that history or biography not only has to be illuminating, but history and biography should be entertaining, and that’s something we don’t talk about anymore.

You know, history done well and written well is entertaining. It’s fun. On American history, there’s McCullough and Joseph Ellis and Walter Isaacson, and Thomas Fleming is another. They’re narrative historians who tell a story and tell it well. They’re illuminating and they’re entertaining.

Now, it’s important to realize that their work is built on a lot of spadework done by historians—burrowing very, very deep, and studying very particular aspects—which then is reutilized by these historians. I do really appreciate this other very fine-grained scholarship, but it’s also important that its discoveries be communicated to larger audiences, especially when we’re talking about this important story of America.

HUMANITIES: You came to Washington, D.C., from Bloomington, Indiana, in 2001. And you’d been to D.C. before, of course, not least as a member of the National Council on the Humanities. But what were some of your impressions of D.C. and its inhabitants when you first arrived? You might start with saying whether it’s true that if you want a friend in Washington, you should get a dog.

COLE: Actually, you should get a couple of dogs because the first one may not turn out to be trustworthy. But, yes, I had been to Washington a lot of times, though I had never lived here. And I remember, in late 2001, going to the National Gallery and looking at my watch and thinking, this is great. I don’t have to catch a plane. I can stay here as long as I want.

Washington is just a terrific city. I have loved every minute of living here. When we first came, we lived in an apartment on Connecticut Avenue. Then we bought a place right in downtown Washington because we wanted to be in the city, and it’s a wonderful mix of absolutely fascinating politics. I’m an observer of politics and people, and there’s a lot of intellectual firepower in the think tanks here, a tremendous amount. I don’t think people realize that about Washington, about how many incredibly talented, learned, and smart people are here. And it’s a wonderful place for culture, museums, and

libraries, and opera, and symphony.

It’s got it all, and in a pretty small package. It’s a manageable city. You don’t have these huge intimidating skyscraper canyons like you do in New York, and everything’s built pretty much to the same height and it’s very easy to get around.

So you feel comfortable, and from where we live we walk almost everywhere. I think we liked Washington right away, and then even more as we got to know it in these seven years.

HUMANITIES: Let’s talk about the Endowment. I heard of a visiting panelist who came here and who apparently served quite well on the panel, but he introduced himself by saying that he was very glad that after several years of a Republican administration that the NEH still existed.

You know that funding for NEH has actually increased under this administration, but you personally have played an interesting role in all this, by reminding people that it is possible to be a member of the GOP and a staunch champion of the humanities at the same time. So, I wonder if you’d take a moment to say why federal support for the humanities is important.

COLE: Well, for starters, I don’t think there’s any sort of dichotomy between being a member of the GOP or being a member of the Democratic party and supporting the humanities. I think the humanities should be viewed apolitically. The only litmus tests we have applied to grant applications were for significance and quality, but I have to say the administration has been enormously supportive of our efforts. The We the Peopleprogram was launched in the Rose Garden with the president. Historically, the Endowment has done very well under Republican presidents, but we’ve had broad bipartisan support on the Hill. People from all across the political spectrum have, especially with We the People, realized that this is a vital issue for our country.

There’s been broad administration and bipartisan support, and I’m very proud of that because in these very tight economic times, appropriated dollars are hard to come by.

HUMANITIES: Your chairmanship began shortly after terrorists hijacked three airplanes and crashed them into the World Trade Center, the Pentagon, and a field in Pennsylvania. How did September 11 affect your work at NEH?

COLE: I was confirmed on the 14th of September and I think September 11 amplified our work in two ways.

We’ve already talked about how I was interested in the more public role of the humanities. Secondly, it brought into sharp relief a problem I’d often thought about as a teacher, namely, the lack of historical knowledge among my students. Many of them had only scanty knowledge of history. They did not know the basic facts of American history, let alone world history. I remember taking a class to a museum and talking to them about a series of Picasso prints called The Dreams and Lies of Franco. While talking about Picasso and Franco and the Spanish Civil War, which, after all, is not ancient history, I looked around and realized that no one had any idea what I was talking about.

On 9/11, we were attacked because of our values and our ideas, our modernity, our equality, the equality of women, our freedom of worship, all our rights. And I thought, we need to know what these rights and values are. Around that time, there were a couple of alarming surveys. The NEAP Survey in 2000 surveyed fourth, eighth, and twelfth graders. And there was a survey from Roper that showed an alarming lack of knowledge among K-12 students. Starting with the Founders, we Americans have believed that education and knowledge of our history and our rights and our responsibilities and our founding documents are important because we aren’t united by blood or by land or religion or race.

What unites us are these ideals, ideals and ideas found in the founding documents. This country of immigrants has succeeded because there has been an understanding of and allegiance to these great principles.

But if our citizens, especially the young people, don’t know what they are, then democracy is in peril. You can’t know where you’re going unless you understand where you’ve come from, and so this very much coincides with the mission of the Endowment, which says in our founding legislation that democracy demands wisdom and vision. So I thought there was an urgency about this. The administration and members of Congress did as well.

HUMANITIES: So, what is We the People?

COLE: Among other things, We the People is now probably the biggest single line item in our budget. When I came in 2001, it didn’t even exist. We the People is devoted to the understanding of American history and culture among our citizens but especially our young people and We the People money helps teachers improve their subject matter knowledge. It funds films about American history and culture. It helps preserve archives. It supports scholarship on American history and culture. It supports challenge grants, which help spread and deepen public understanding of founding principles and their ramifications, and increases funding to the 56 state and territorial humanities councils who have been tremendous partners in this and have taken We the People funds and used them to disseminate knowledge about American history and culture in their own states. And the biggest subset of We the People has been Picturing America, a program that sends forty high-quality reproductions of American art, a whole span of American art, to tell the story of American history and culture, supported by all sorts of terrific educational material. The amazing thing about Picturing America is that we will make around 75,000 awards to schools and public libraries, Department of Defense schools, 20,000 Head Start centers, embassies, and home schools.

That number is greater than all the grants the Endowment has made in its forty-three-year history.

HUMANITIES: There are more Picturing America awards than there are all other NEH grants?

COLE: Yes.

HUMANITIES: Really? That’s amazing.

COLE: These Picturing America sets will be in tens of thousands of schools, where they will reach millions of students, and public libraries, where they will reach millions of library-goers for decades. So, you know, you could plot it out. They’re already reaching millions and millions of students.

HUMANITIES: You helped select and approve all forty images, but is there one in particular that’s any more dear to you than the others?

COLE: I love them all. There is one that I did not know before we began our research that is incredibly moving. Moving in its content and moving in its form. That’s James Karales’s Selma-to-Montgomery Voting rights march in 1965 photograph. But they’re all fascinating and wonderful works. Our citizens, especially young people, are bombarded by images, millions and millions of them, most of them junk, but these images have stood the test of time. They are rich in meaning and in form, and as the students move through the grades, these will bear repeated looking and contemplation. And they will change as these students mature, not because the reproductions actually change, but the students will bring more and more to them as they mature themselves.

And the other wonderful thing about Picturing America is that it makes available a set of images that millions of students will have in common, and that’s not true for a lot of educational material.

HUMANITIES: If you had to write the position description for the chairperson of NEH, what would it say?

COLE: Well, I think the first thing you would say is you’ve really got to love this job. For me it’s not even a job. It really is more of a cause than a job, but I think it demands a couple of things. One is the ability to oversee the grant-making process and to make sure that at the end of the day everything the NEH funds is of the highest quality, the best of the best, because our money is all taxpayers’ money and we have a responsibility to make sure it is spent effectively and efficiently.

So that’s the first responsibility. The second, I think, is to work effectively with a variety of entities that intersect with the NEH. The White House and the Congress are important, and then there are all the groups funded by and interested in the Endowment, from state councils to scholarly societies to documentary filmmakers and teachers and archivists and librarians. You have to understand what their needs are and try to be responsive. Another responsibility is to use the chairmanship as a bully pulpit: you must try to identify what the most relevant and significant issues are, and get out there and talk about them.

My advice to my successor is, Don’t try to do everything. Just try to do a couple of things, but try to do them really well.

I only wanted to do a couple things. The first was to make sure the Endowment was only awarding funds to the highest-quality applications. That’s Job Number One.

Next, I wanted to do a couple of major programs. One was We the People and all its subsets, Picturing America being the foremost.

Another thing was to establish the office of Digital Humanities. The digital humanities constitute a new frontier of the humanities, in terms of dissemination, nationally and internationally, and because they offer opportunities to ask new questions, new ways to discover and analyze humanities material.

We also forged new international ties. I always thought my science colleagues had more international ties, and the Endowment didn’t have many. Now we’ve been able to forge memoranda of agreement with many countries.

We worked with the State Department, with UNESCO, and other entities, in order to spend our money more effectively and because much of this work we can do in partnership with other federal agencies.

HUMANITIES: As a result of your cultural diplomacy, you’ve been knighted. Is that what you are? You’re a knight?

COLE: Yes. Well, yes.

HUMANITIES: Should I call you Sir Bruce?

COLE: No, no. Yes, I was very grateful to be made a Knight of the Grand Cross, which is the highest honor the Italian government bestows.

HUMANITIES: Does it come with a suit of armor?

COLE: No, but it comes with other great stuff, like a sash and medals and the like. And that was very gratifying.

HUMANITIES: You’ve done a fair amount of travel as chairman. Were there any trips worth mentioning before we go?

COLE: They were all fascinating, and it was really wonderful to see parts of the United States I had never seen before. And it was great to go abroad. One of the biggest trips was the China trip, where we worked with the Chinese cultural authorities to have a major conference on digitizing. The Chinese government asked us to visit some sites away from major cities. I had been to China before, but this offered a wonderful new perspective on the country.

HUMANITIES: What are you doing after you leave NEH?

COLE: I’m going to be the president of the American Revolution Center, which is going to be a museum and education center, the only one dedicated to the Revolution. You know, there are museums for plastic, bricks and thimbles, and even SPAM, the kind you eat, but there is no museum dedicated to the Revolution, the event that not only made this country but made the modern world.

All of our freedoms—to express our opinions, to read a newspaper, to associate, to worship where you like, to vote—all that comes from our founding documents, made possible by the Revolution. This museum will be a living memorial to the Revolution and will fill, I think, a huge gap.

HUMANITIES: What is the significance of Valley Forge?

COLE: Valley Forge is a hinge moment in the Revolution. It is where, after a series of defeats, Washington led the Continental Army to establish a winter encampment in 1777–1778. It was an extremely hard period for the Army and there was much privation, but it was also a turning point, a time of retraining and renewal and rededication to purpose. It was at Valley Forge where this really bruised and battered ragtag army wintered, came together, and then went on to triumph. So it was an iconic moment in our history.

HUMANITIES: Thanks very much, Sir. It’s been a pleasure.

COLE: You’re welcome.