Henry Francis du Pont (1880–1969) was an intensely shy, private man, so likely he wouldn’t have minded being overlooked. But as a horticulturist, the situation outrages me. Du Pont has never received the recognition he deserves as one of America’s greatest gardeners. Indeed, what he created at Winterthur, the family estate outside of Wilmington, Delaware, remains nearly forty years after his death a quietly revolutionary masterpiece, still far ahead of contemporary American landscape design. To overlook this is more than an injustice; it is for all who love gardens an opportunity wasted.

Harry, as he was known to friends and employees, is of course hardly an unknown. A pioneer in the appreciation of Early American decorative arts, du Pont included in his collecting not only furniture, ceramics, and textiles, but often whole houses when he found a structure with architectural features, plasterwork or wooden paneling, perhaps, he felt were outstanding. All of this, tens of thousands of objects, each one personally and carefully selected, he assembled in a designed-for-the-purpose, one-hundred-and-seventy-five period-room mansion he built on the Winterthur estate.

Characteristic of du Pont’s genius is the way in which he displayed his finds. He assembled selections of furnishings that were related not only in period and provenance but also aesthetically, playing one off against the other in roomscapes that ranged from subtly powerful to the brilliantly unexpected. Always, in du Pont’s hands, the sum was far greater than the parts.

This is why Winterthur has been, ever since it opened to the public in 1951, a place of pilgrimage not only for historians and curators but also for interior decorators. It’s also why Winterthur’s sixty acres of gardens should be a destination for those who want to incorporate natural beauty into their personal environments.

The fact is that H. F. du Pont worked on the gardens even longer than he labored over his collections of decorative arts. He planted and maintained his own garden while a teenage boarder at prep school, and borrowed space in a nearby commercial greenhouse to grow sweet peas and other flowers for cutting. As an undergraduate at Harvard he enrolled in the Bussey Institution, a division of the university that offered practical instruction in horticulture, and began his lifelong association with Harvard’s Arnold Arboretum, whose famous director, Charles Sprague Sargent, was then dispatching expeditions all over the world to seek out new plants to enrich American gardens.

Some of these prizes went to the Pinetum that Harry was then planting at Winterthur with his father. In fact, correspondence between the du Ponts and Sargent reveal that the arboretum director treated Winterthur as a southern outpost, relying on reports from its gardens to help clarify what climate and conditions best suited species newly imported from abroad. Nor did the association end with the deaths of du Pont senior and Sargent. One of the most remarkable plant specimens in the Winterthur gardens, in fact, is a huge dawn redwood (Metasequoia glyptostroboides). This tree, which had previously been known only in fossils, was discovered in 1943 still surviving in a remote area of central China. In 1948, the Arnold Arboretum received some of the first samples of seed to reach the outside world; in 1951, Harry in turn received one of the seedlings raised from these. Today the Winterthur metasequoia stands over one hundred feet tall with a trunk that measures almost five feet through at chest height.

Harry’s introductions were more than just botanical, however. During trips abroad before the First World War he visited Gertrude Jekyll at her pioneering garden, Munstead Wood, in Surrey. Du Pont’s color-sensitive eye delighted in the painterly way that Jekyll combined flower and foliage colors—you can see the evidence of this today in such areas of the Winterthur landscape as the peony garden, a superb collection of herbaceous and tree peonies, and Winterhazel Walk, where in early spring the soft greenish yellow blossoms of winterhazels (Corylopsis glabrescens) play off the lavenders of Korean rhododendrons.

Another crucial encounter occurred during du Pont’s 1912 trip to England when he met William Robinson, the leading apostle of the “wild garden” style of plantings which advocated combining hardy plants in an informal, seemingly uncalculated arrangement. To make an impact with such understated planting requires outstanding mastery of texture and mass as well as color. These were the talents that were ultimately to make du Pont famous as an interior decorator, but he demonstrated them decades earlier in the March Bank, a wild garden he developed on a wooded, south-facing slope in front of the Winterthur mansion.

Du Pont actually began this project before meeting Robinson; it was initially inspired by what he had already been reading in Robinson’s books. In 1909, du Pont planted twenty-nine thousand bulbs in this area, adding another thirty-nine thousand the following year. Each one of these bulbs was carefully, individually placed. Today, almost a century later, these bulbs continue to thrive and multiply, testifying to du Pont’s skill as a horticulturist. The drama begins in January with patches of chaste snowdrops, buttercup-like adonis (Adonis amurensis), golden winter aconites (Eranthis hyemalis) played off against lavender-blossomed early crocuses—lavender and yellow was to be a juxtaposition du Pont employed in interiors as well. By mid-March, there are vast carpets of electric-blue scillas, white glory-of-the-snow, and yellow daffodils. White daffodils replace the yellow, providing counterpoint for Virginia bluebells, followed by hostas, bellflowers, fairy candles, and daylilies on into summer.

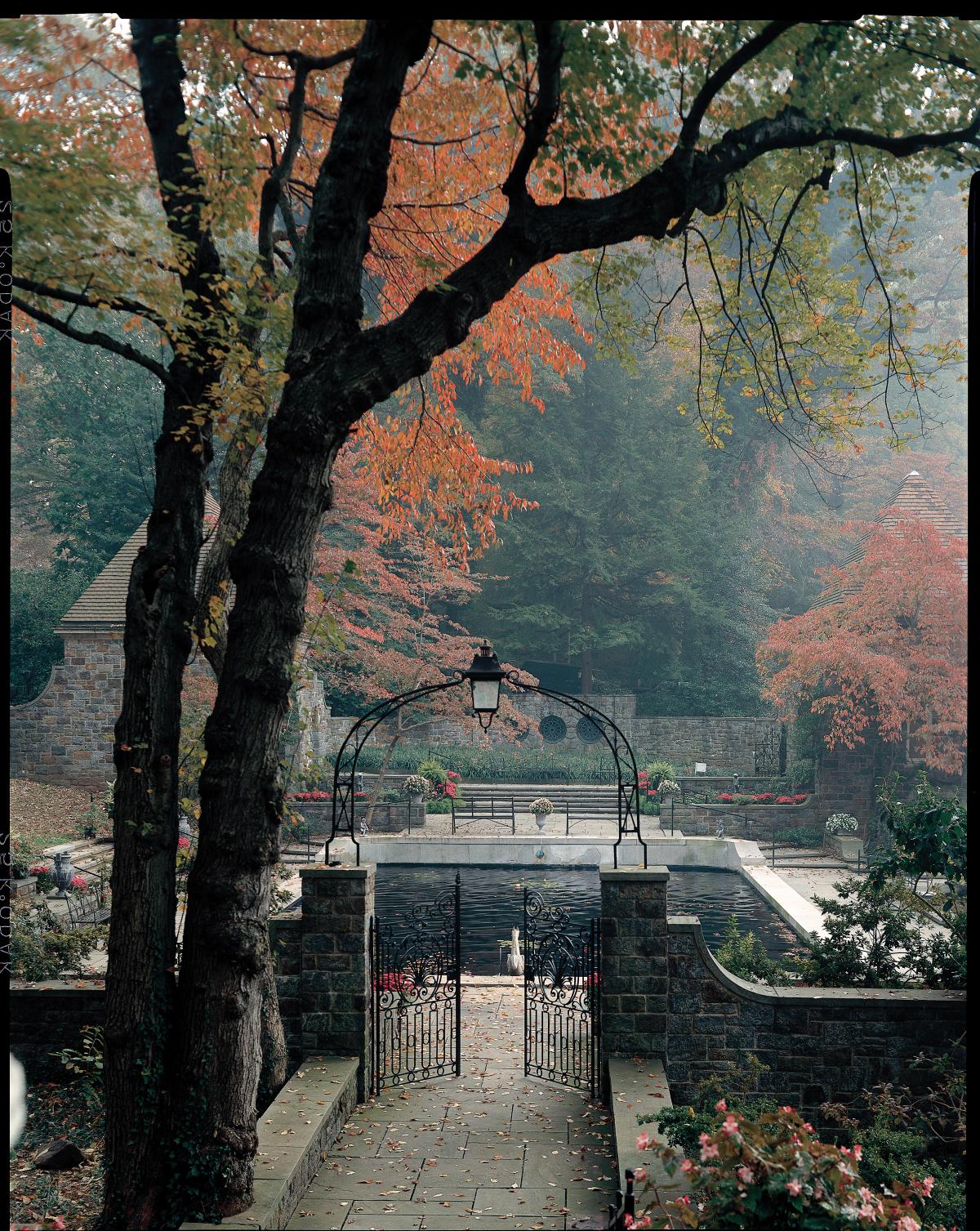

Another extraordinary example of wild gardening at Winterthur is the Azalea Woods du Pont created by weaving thousands of Kurume azaleas and wildflowers through several acres of forest thinned by the attack of chestnut blight. He also gardened, however, in a more formal style, collaborating often over the years with a childhood friend, the pioneering female landscape architect Marian Coffin. Together they turned former tennis courts into the Sundial Garden, concentric circles of flowering trees and shrubs, and the Reflecting Pool, a series of descending terraces and views ending in what was, in du Pont’s day, a swimming pool, but which is now preserved as a serene aquatic mirror. Even in such settings, however, the geometry of the architecture is played off against fluid plantings in which shrubs, flowers, and trees, both native and imported, are made to look as if the perfection of their siting is a natural accident.

After H. F. du Pont’s death, Winterthur’s gardens suffered a period of neglect as the museum staff concentrated on the curation and expansion of the decorative arts collections. Fortunately, a recently completed, twenty-year program of restoration has returned the landscape to full glory. Now museum personnel such as Maggie Lidz, estate historian, are taking on a new challenge: exploring the uniquely intimate way that the Winterthur house relates to its landscape.

Connecting house and setting is a goal for virtually every architect and gardener. The classic device is to plan the views from the house’s windows, arranging the landscape to present carefully composed, painting-like vistas from the more prominent rooms. Du Pont, however, sought a more fundamental connection, practicing what J. Thomas Savage, Winterthur’s director of museum services, describes as “interiorscaping.” Du Pont translated his experience from outdoors to in. Green, for example, became the coloristic foundation within the house. Du Pont’s color sense was exquisite and adventurous, expressing itself in countless dramatic contrasts and harmonies, but it is green that provides the ground. Curators have identified some seventy-two different shades of this color in the interior paints alone

.

Flowers, likewise, were almost as prominent indoors as out. Eighteen gardeners tended four acres of flowers, all meant for use as cut flowers in the house, and an acre of greenhouse space to ensure that the supply would continue unbroken through the winter. John Feliciani, director of horticulture, recalls as a boy going with his father, the cutting-garden foreman, early in the morning to bring samples of whatever was in bloom, while the butler brought bowls and vases, so that Mr. du Pont could select the combinations to be displayed that day. For more than half a century du Pont kept written records of his choices to ensure that guests would never have the same experience twice.

As many as twenty-five large floral arrangements would be created for a single room. Each arrangement typically featured only one type and color of flower; in this way the whole room became a grand bouquet of contrasting and complementary textures, perfumes, and colors. Du Pont used florals in the wallpapers, ceramics, and textiles to relate the furnishings to the flower arrangements and to the garden; he even changed drapes and slipcovers in many rooms seasonally so that the color themes of the interior decoration would harmonize with what nature was presenting outdoors.

Confronted with this intricate, astonishing display, the visitor is tempted to dismiss du Pont’s gardening genius as something of no relevance to the average life. Yet what makes Winterthur unique is not just the lavishness of its furnishings or plantings. It is H. F. du Pont’s special understanding. He was a pioneer in awakening Americans to the fact that our own decorative arts—the daily objects from our own past—are as worthy of study as any European or Asian antique. If we let him, he could change our relationship to our gardens as well.