John Ledyard (1751-1789) came to be one of the best known Americans of his time. And yet his life comprised a series of failures, increasingly grand, but failures all the same. As a young man, he slipped away from Dartmouth College in a canoe, his character in question because he failed to pay his debts. He failed in bids to enter the Connecticut Bar and the Congregational clergy. He failed in business, and his most ambitious journeys as a professional traveler and explorer-from which the fame he did achieve before and after death at the age of thity-seven derived—all ended in failure. But as an explorer, a travel writer, and an observer of his own time, Ledyard was remarkable. What set him apart was his deep understanding of the fundamental social fact of his age: Being somebody in late eighteenth-century America meant being somebody known to the right kind of people. And Ledyard rarely failed at gaining the attention of the right kind of people.

The list of famous individuals he came into contact with during his short life comes straight out of the indexes of history: Captain James Cook, on whose last voyage he sailed as a lowly marine; Robert Morris, financier of the American Revolution and Ledyard's one-time employer; John Paul Jones, with whom he struck up an acquaintance and tried to raise funding for an ambitious expedition to the northwest coast of America; Ben Franklin, whom he met in Paris during Franklin's last days as American ambassador there; Thomas Jefferson, Franklin's successor, whom Ledyard also met in Paris. The list goes on, but it seems just as well to stop here. For it was in Paris that Ledyard enjoyed his first great social success, when he was accepted into the famous expatriate circle surrounding Thomas Jefferson.

In true Quixotic fashion, soon after arriving in Paris, John Ledyard fell upon fleeting good fortune once again. He met the former American naval commander and Revolutionary War hero John Paul Jones.

The Scottish-born Jones, who was just four years older than Ledyard, had come to Paris in late 1783 to collect prize money owed American sailors and officers by their French allies.

While he waited for his money, Jones contemplated a return to commercial seafaring, and when Ledyard showed up with his plans for exploring the northwest coast of the American continent, the ever-daring Jones quickly seized on the idea. In the summer of 1785, he and Ledyard made plans to take two ships to the northwest coast, where they would establish a trading factory (literally, the residence of the factor, or middleman) staffed by a surgeon, a clerk, and twenty soldiers. Ledyard would be paid to represent others' interests. As the factor, he would set the terms of trade with local natives and manage the movement of goods to and from the factory. After six months, one of the ships would sail to China, loaded with furs. That ship would then return with additional trade goods, and six months later both ships would leave for New York, by way of China. Ledyard would remain to manage the factory until the ships returned to start the circuit again, an arrangement that would leave him at the remote outpost for up to seven years.

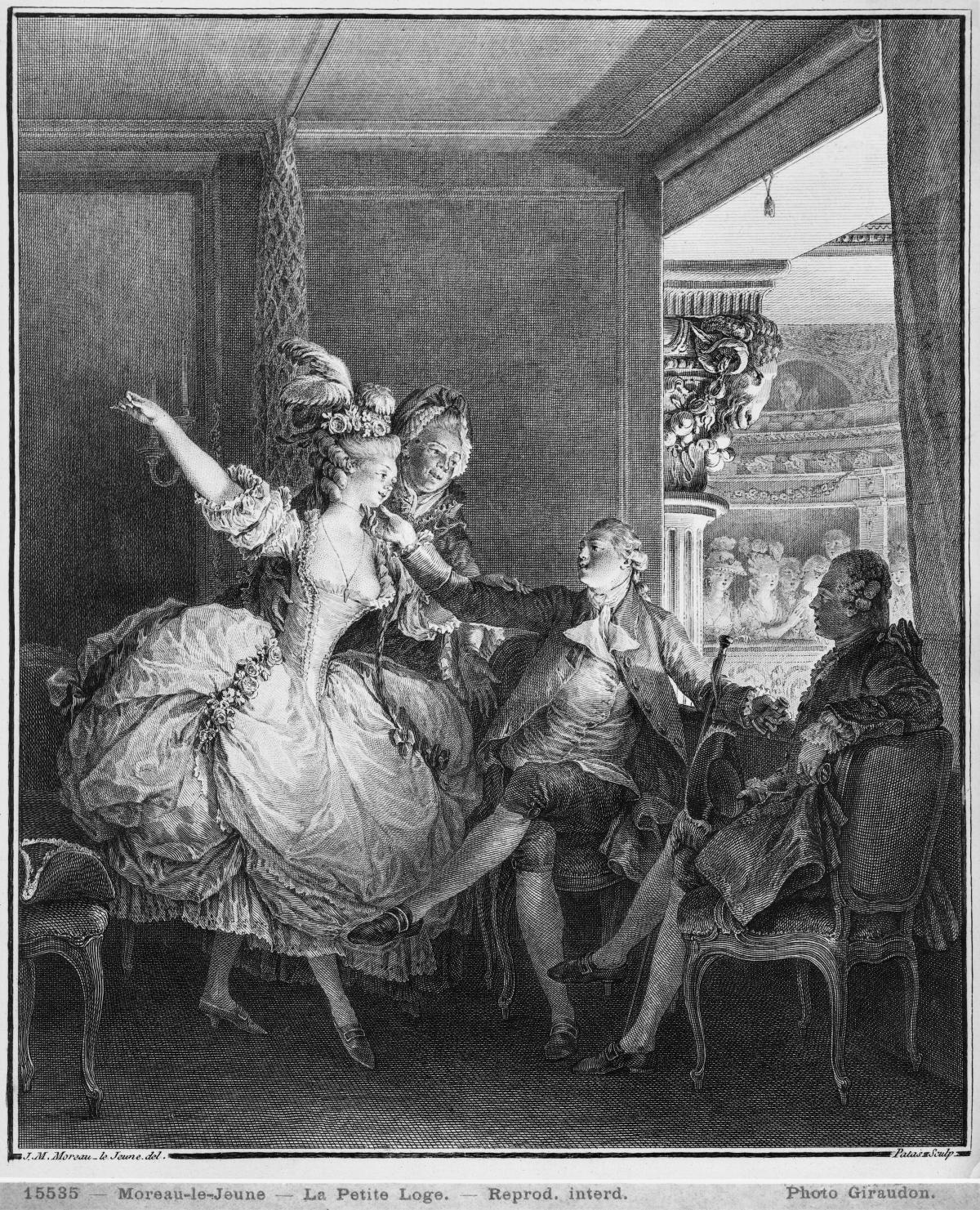

The experience he gained sailing with Captain James Cook for four years—part of the time along America's northwest coast—and what he learned from his encounters with American Indians presumably made Ledyard, in Jones's eyes, the ideal factor. And in Jones, Ledyard found a patron whose fame would lure investors. With the possible exception of Benjamin Franklin, no American was more widely admired by the French. The king had personally received him and made him chevalier of the order of Military Merit. And when Jones appeared at the grandiose Paris Opera, he was greeted with enthusiastic applause.

During the summer and fall of 1785, Jones traveled back and forth between Paris and Lorient, organizing financing and procuring ships and crew. Meanwhile, Ledyard awaited his commercial fate in the cultural capital of the universe. Never had his social life been better and never had he lived so comfortably for so long. With Jones's help, Ledyard became a fixture in the American expatriate community of Paris, circulating from one dinner to the next in the company of Thomas Jefferson (who arrived in France in August 1784 and would replace Franklin the following spring as American minister there), the Marquis de Lafayette, two sons of the venerable Fitzhugh family of Virginia, and assorted other American and French notables. It was, unquestionably, a gentleman's life, and it was a life that gave Ledyard time to reflect on himself and the extraordinary place that was Paris on the eve of the French Revolution.

The time in Paris also allowed Ledyard to make writing a part of his daily life once again—although in a way very different from his days aboard Cook's ship. Now, writing had become a private, solitary kind of affair. As he explained in a letter to his cousin Isaac, he had acquired the habit of writing with quill in one hand, glass of wine in the other, and sitting "naked two or three hours before I sleep & in the same unconstrained situation I think & occasionally write my friends." What better proof could there be that "I write without a disguise"? This characteristic disdain for artifice shaped a dense eleven-page Paris journal Ledyard appended to one of his letters to Isaac. It also revealed the continued animating philosophy of his life, a philosophy that left him appalled by the outlandish Parisian excesses he was beginning to notice.

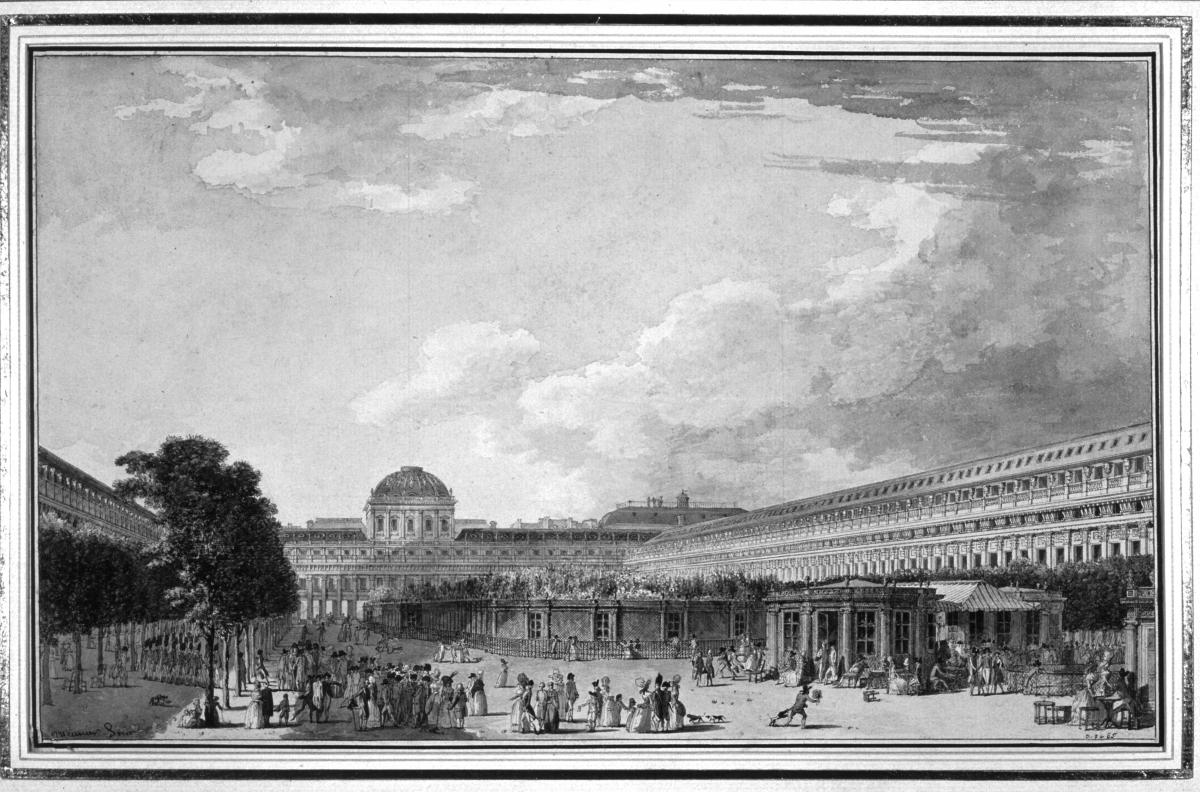

It is hard to imagine a place more unlike the Connecticut of Ledyard's youth than Paris under the old regime. Densely populated, flooded with agitated artisans, impoverished apprentices, hack writers, and dissipated aristocrats, governed not by local magistrates or town councils but largely by an immensely powerful and pervasive police force (of which Ledyard most ardently approved), Paris was about as foreign a place as a New Englander could find without leaving the European world. Like any provincial fending off the seductions of a chaotic capital city, Ledyard was at once repulsed and captivated by what he saw. This reaction was especially evident in his response to one of Paris's great edifices, the grand Palais-Royal.

The Palais had been inherited by the duc de Chartres from his father, Louis XIV's brother, the duc d' Orléans. Seeking to make the most of this part of his patrimony, the entrepreneurial duke undertook a revolutionary building experiment. He would transform the Palais and its gardens from a place of pleasant pastoral relief to a kind of city within a city.

As an act of entrepreneurship, the plan was pure genius. Here, in the heart of Paris, aspiring lawyers, merchants, and minor gentry could enjoy the fruits of their prosperity sheltered from the ordinary urban bedlam outside and free from the scrutiny of city authorities. In the arcades surrounding the Palais gardens, these Parisians could shop and be entertained at one of the many jewelers, silk merchants, tailors, museums, bookstores, and private clubs the duke counted among his tenants. In the Palais gardens themselves, visitors enjoyed additional high and low entertainment, ranging from theatrical performances and magic shows to the freakish displays of a hugely fat man and a wax figure purported to be the preserved body of a two-hundred-year-old woman

In the time Ledyard began frequenting the Palais, the liberties afforded this peculiar duchy within Paris had begun to yield its own kind of bedlam. The Palais had become a center of illicit commerce—commerce in hearsay, in forbidden pamphlets and books, and, of course, in sex. Though he spent much time at the Palais, the scene disgusted Ledyard. “The professed pride of the Ville de Paris,” the Palais, he wrote, “is a vile cinque[sic] of pollution” populated by “bawds, pimps,” their clients, and "those who by the glare of dress, equipage, or assumed titles hide their worst deformities." The latter were, no doubt, deformities of character. For the very “apartments of this . . . rich and elegant building are inhabited by coarse bred impudent abandoned and disgusting bawds . . . and impoverished young debauchees without pretension to family, fortune, or education.” The debased sexual commerce of the place infected the most precious bonds of family. “I report for absolute fact,” Ledyard concluded, “that the father, the mother, and the daughters are here for the sole and professed purpose of mutual prostitution.”

For all the venom it elicited from him, Ledyard could not resist the temptations of the Palais. One night after dining with Jefferson, he reported that he and the American envoy took a walk in the Palais gardens. After Jefferson retired for the evening, Ledyard continued strolling and heard someone calling his name. He was being propositioned by a prostitute and soon found himself entwined with this lady, “making a thousand protestations of eager desire and eternal passion.” The encounter was of the most superficial and unsatisfying variety. For it occurred several feet from the woman's “four feet five inches husband . . . a true Parisian husband.” In a moment of unintended emotional transparency, Ledyard concluded that “it will not be her fault if I never see her again nor will [it] occasion her more than five minutes pain or pleasure whether I do or not.”

Ledyard's new friend Jefferson was also entranced by the Palais, though for different reasons. To Jefferson, the remarkable thing about the building was not so much its illicit trade or its architectural beauty as its prospects as a model for real estate development. Less than six months after arriving in Paris, Jefferson reported to his friend the Richmond physician James Currie that if a similar palace were built in Richmond it would bring its owners great profit. Here there would be a carefully sheltered common, with no toiling slaves or laborers, ideally suited to the strolling sensibility of the genteel. Around the square would be precisely the kinds of shops and accommodations that “would make it the resort of everyone for either business or pleasure, thus rendering it the best stand for persons of every object and of course entitling it to the highest rents.” Jefferson was serious enough about a Virginia version of the Palais to earmark five hundred pounds for the project and to recruit a group of European artisans to build the building.

Given this enthusiasm, one wonders whether Jefferson saw the same Palais Ledyard saw. Perhaps the Virginian simply thought the gaming and prostitution of the Parisian Palais would be unwelcome in a similar American structure; or perhaps he never actually saw the darker, carnivalesque side of the great palace, although that is certainly doubtful. At the very least, there is reason to believe Ledyard would have shared his own critical observations with the American statesman.

Ledyard had joined the circle of Americans who congregated around Jefferson's residence, some of whom in fact lived in the residence. The group included Jefferson's secretary, William Short, and the Connecticut-born David Humphreys, designated by Congress to negotiate foreign trade treaties. Ledyard became especially close to Humphreys, a noted poet and patriot. Though “devoutly fond of women, wine, and religion, provided they are each of good quality,” he was, Ledyard wrote, “a sincere Yankee and so affectionately fond of his country, that to be in his society here is at least as good to me, as a dream of being home.” Others in the circle included Colonel David S. Franks and Thomas Barclay, also members of the new American diplomatic corps. Then there was the parade of prominent Americans who passed through the Jeffersons' house seeking passports, assistance with trade deals, and other favors.

To Ledyard, this expatriate circle was most agreeable. Not only did it provide him with a new circle of literate, aspiring young gentlemen against whom to judge himself, but it left him feeling positively flush. Compared to him, he wrote, “such a set of moniless rascals have never appeared since the epoch of Falstaff.” More important, among even these “moniless rascals,” Ledyard was well known. When Ledyard mocked Humphreys's poetry in Jefferson's presence, Humphreys rebuked him, reminding the audience that a man who returned from college cowering under a bearskin in a giant dugout canoe, as Ledyard had, was unlikely to have sound literary judgment. In his journal, Ledyard noted proudly that Jefferson responded with a laugh and the astute observation that the trip “was no unworthy prelude to my subsequent voyages and that I had [displayed] a great consistency of character from that moment to this.” In Ledyard's world, a man could hardly receive higher praise.

Not surprisingly, Ledyard came to admire Jefferson. The tall, thin, and graceful American minister, eight years Ledyard's senior, struck him as unusually dignified and upstanding, an ideal representative for the young nation. Ledyard even came to feel that Jefferson was better suited to the job than the great Franklin, whom Ledyard had met when he first arrived in Paris. It was not so much that Franklin was a lesser man but rather that Jefferson simply seemed a more noble figure. Eschewing Franklin's showy Americanisms and his enthusiastic embrace of Parisian culture with all its tawdry intrigues, Jefferson presented a more restrained, more cerebral persona. In Ledyard's view, this distinguished him from all the European diplomats, the “lackeys of ministers and kings” who did little more than perpetuate “the pageantries of old sickly kingdoms.” In Jefferson, America had a truly worthy minister: able, striking in appearance, and beholden to none.

Ledyard was also clearly taken with Jefferson's intellect and seems to have absorbed the American's fascination with social and economic reform. In Ledyard's earlier writings there is little social commentary. Insofar as he looked objectively at human beings, it was to serve his ethnological and historical interests. But life in Paris seems to have taught Ledyard to think about the processes and forces that acted on human beings in the present. Most fundamentally, it taught him to think about exactly what is was that made human beings good or bad. The old Puritan morality, that a person was born either good or bad, had clearly lost whatever allure it may once have had for Ledyard. Now the question was, What social forces account for human morality and its absence?

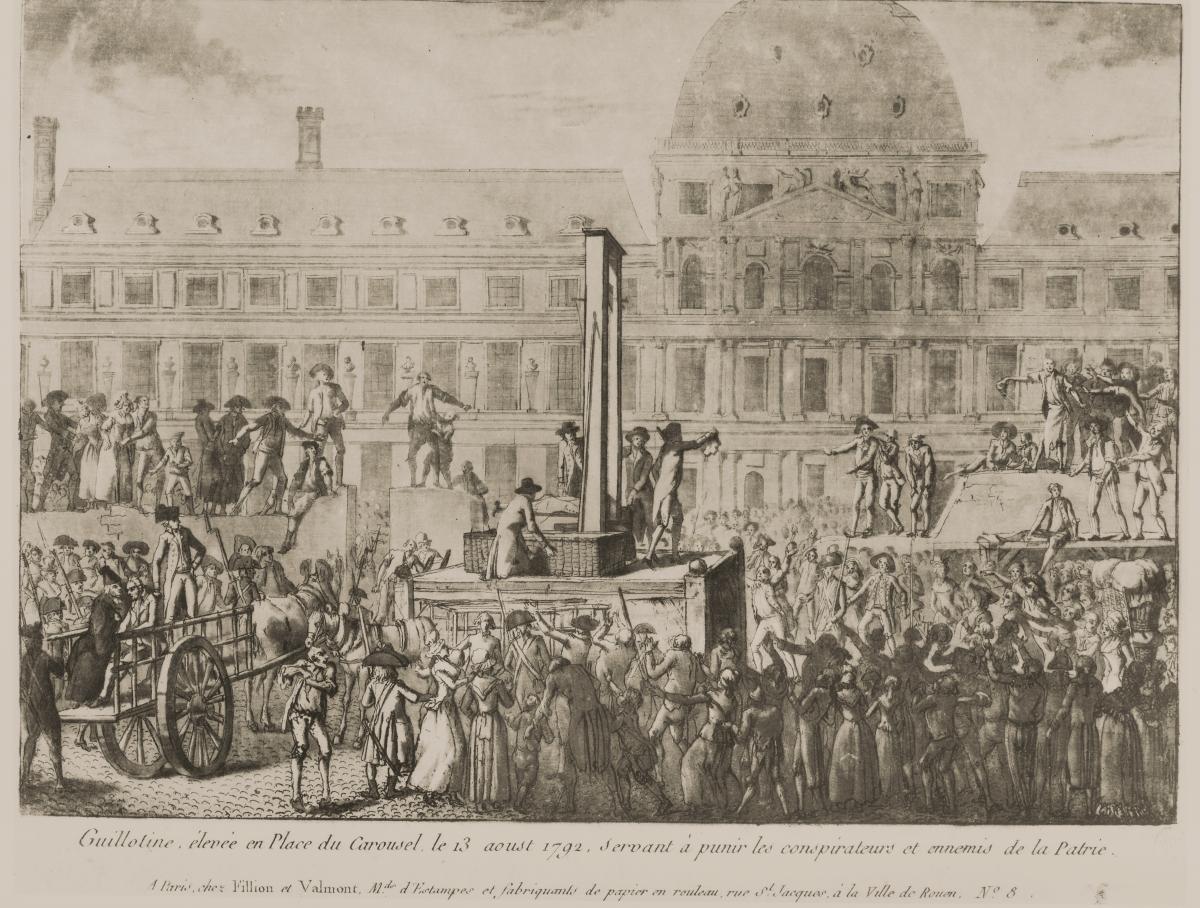

The question was a crucial one for citizens of that novel entity, the United States. If a society was to be governed by the governed themselves, it would have to find a way to ensure the goodwill and common sense of the citizenry. To anyone visiting a European city in the 1780s, this must have seemed like a hopeless challenge. Evidence of a morally corrupted populace was everywhere, from the petty criminals and beggars who filled the streets to the bawds and their gentlemen clients who circulated through the Palais-Royal. For the forward-thinking, enlightened circle of which Ledyard was now a part, the source of these problems was institutional. It derived from human inventions that corrupted true human nature. The most pernicious of these were created precisely to counter antisocial, disorderly behavior: the law and the penal system. European states, these enlightened Americans had come to believe, had failed to grasp the great truth that arbitrary and inhumane punishment begets an arbitrary and inhumane populace. The evidence for this was everywhere in ancien régime France.

For the entire time Ledyard resided there the country was captivated by a series of sensational trials. One of these involved three men accused of robbing a farmer and his wife in a small rural village. With no real due process, the men were convicted and sentenced to death. But their execution would not come in swift, humane form. It would come only after the condemned had been tortured on the wheel, after their limbs had been shattered and their backs broken. For reform-minded Parisians, the whole horrendous affair was a call to arms. The judicial system needed to be reformed; punishment needed to be made to fit the crime, and some form of due process needed to be instituted. As one reformer observed, the accused are brought before the court scarred by their inhumane incarceration. They appear “haggard, disfigured, white from hunger and fear,” with faces “covered with hair like that of a wild beast.” "Who is this being?" the writer asked. “None of his judges know—he is a shadow, a specter, appearing from the depths of a prison cell before judges whose power terrifies him. Of his interest, his character, his morals, who can know anything? Who even asks?” This, then, was a system that turned its charges into faceless beasts, making true justice impossible.

Evidence of the failed penal system was everywhere for Ledyard to see. On a tour of the huge Bicêtre Asylum, he saw several thousand insane, destitute, accused, and convicted prisoners randomly thrown together in the most appalling conditions and overseen by an indifferent militia. To Ledyard's reckoning, between ten and twenty prisoners perished per day, and those were perhaps the lucky ones. By far the sorriest lot were those prisoners convicted of capital offenses whose families could afford a sufficient defense to have the sentence commuted to incarceration. For the families, this was preferable to the humiliations of a public execution; but for the convicted, the fate was worse than execution. “Those offenders,” noted Ledyard, “are let down to a subterracous [sic] receptacle and it is said are never seen or heard of more. But the truth is that they are taken up after a certain time and assassinated and burned in secrecy.”

In addition to discussing France's social problems, Ledyard and his circle almost certainly reflected on the place of the new United States in an unfriendly world. Among the most pressing problems facing the country was the loss of British protection for seaborne trade, especially in the Mediterranean and along the West African coast. Until the American Revolution, American trade in the Mediterranean had been made possible by the British government's purchase of passage from the so-called Barbary pirates plying the seas off North Africa. With American independence, the North African pirates were free to prey on American shipping, capturing ships , kidnapping and enslaving crew members, and otherwise disrupting what had been a major component of American trade. One of Jefferson's preoccupations during his mission was finding a solution to this looming scourge. In the short run, this meant forging diplomatic relations with the Barbary states of Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia.

In the long run, it meant bolder solutions. Not long after arriving in Paris in late 1784, Jefferson advocated a military solution to the Barbary problem, and as president he would send naval squadrons to attack Tripoli. But in the mid-1780s more idealistic solutions were in the air as well, and Ledyard and his dinner companions seem to have embraced them. Given the endless diplomatic imbroglios, the dangers of seafaring, and the caprice of foreign markets, would it not make sense for a republic to free itself entirely from foreign trade? “May America have no ships of war or any merchant ship that shall go off its own coast,” Ledyard wondered, “but like the Chinese command the commerce of all nations that find it their interest to visit her and not suffer by those who do or do not?”

It was, to be sure, an odd perspective for a man banking on empire in the distant Pacific Northwest. But perhaps Ledyard had come to see his own empire-building in a new, Jeffersonian light. Instead of a beachhead for a network of transoceanic commerce, the northwest coast factory would be a western foothold for a new, continental empire. Such an empire, with ports on both coasts and a vast, productive, transcontinental hinterland, could attract foreign merchants to American ports and free American merchants from the hazards of oceanic commerce. Idealistic though it may have been, this Jeffersonian vision of a continental empire was born of very real geopolitical concerns.

Several years before arriving in Paris, Jefferson had written to fellow Virginian and Revolutionary War general George Rogers Clark about an alarming British proposal to explore North America from the Mississippi to the California coast. “They pretend it is only to promote knowledge.” But, Jefferson added, “I am afraid they have thoughts of colonizing into that quarter.” Jefferson even proposed that Clark lead an expedition to the region to preempt the British plan, but Congress had neither the will nor the means to support such an ambitious project. Something, Jefferson presumably concluded, needed to be done to counter this danger.

Undoubtedly, the prospect of giving up the far west to a colonial power like Britain was all the more disturbing if, as so many still hoped, there existed some sort of water route from the west coast to the Missouri or Mississippi river. If seized by a European power, such a navigable artery would facilitate foreign control of the far west and the lucrative China trade. Its existence had been suggested by a popular travel account that Jefferson had carefully studied, Jonathan Carver's Travels in the Interior of North America, published in 1778. Carver claimed that a series of great rivers descended from the center of the American continent, probably in the great “shining mountains,” as he called the Rockies, in reference to “a number of crystal stones, of an amazing size, with which they are covered, and which, when the sun shines full upon them, sparkle so as to be seen at a very great distance.” The headwaters of these rivers were “within a few leagues of each other.” If one followed the Missouri to its farthest western point, one could relatively easily portage to the “River Oregon, or the River of the West, that falls into the Pacific Ocean.”

The possibility that the British or some other European power would discover this water passage had thus been a serious concern for Jefferson. After his arrival in Paris, that concern grew. Jefferson discovered that the French navigator and Revolutionary War hero Jean François de Galaup, Count de Lapérouse, was preparing to lead an exploratory voyage to the North Pacific. The secretive naval voyage ostensibly had purely scientific purposes. But Jefferson believed Lapérouse's two ships were being outfitted with less benign intent, and he asked Jones to look into the matter. In a letter to John Jay, the American secretary of foreign affairs, Jefferson explained that his gravest fear was that the French had designs on the new frontier of European colonialism, the American northwest coast. “If they should desire a colony on the Western side of America,” he warned, “I should not be quite satisfied that they would refuse one which should offer itself on the Eastern side.”

It turns out that Jefferson's suspicions were partly correct. At almost the same time Jones and Ledyard were planning their voyage, the French minister of ports and arsenals, Claret de Fleurieu, began exploring the possibility of a French-sponsored northwest coast venture. Fleurieu even went so far as to consult the Dutch-born merchant William Bolts, who had long been planning a trading voyage to the region (including one in 1781 under the Austrian flag) and who had some influence on the French venture's final form. What Jones discovered was alarming; this was no pet project of a few inspired ministers. It was directly endorsed, designed, and underwritten by Louis XVI himself. Among the other goals “worthy the attention of a great Prince,” Jones explained to Jefferson, one was “to extend the Commerce of his Subjects by Establishing Factories at a Future Day, for the Fur Trade on the North West Coast of America.”

While the French prepared to stake their claims to the northwest coast, Ledyard's partnership with John Paul Jones collapsed. The reason for this latest failure is not entirely clear, but timing must have been a factor. As the two Americans pursued French ships and investors for their scheme, news of Lapérouse's departure was beginning to circulate. And it is hard to imagine any French merchants or sea captains embarking on an enterprise that would so clearly compete with the Crown's own plan. Even if some had been willing to do so, the timing would have been poor.

By 1785 at least one British vessel, the relatively small sixty-ton brig Sea Otter, had reached the northwest coast, and by the time Lapérouse sailed in August 1785 two other British ships, the King George and the Queen Charlotte, both under the command of veterans of Cook's voyages, had left from Britain bound for the northwest coast. The British were also beginning to outfit ships in India and China for the Pacific trade, and no fewer than seven expeditions arrived on the northwest coast during 1786, the year Jones and Ledyard's ships would have arrived there. This stampede to the region would have given any sensible investor pause, as purchase prices for fur would no doubt rise while sale prices fell in a flooded Chinese market. For American merchants, the trade would not become profitable until the 1790s, when the French Revolution began taking its toll on French and British maritime resources.

Ledyard's prospects in the fur trade had collapsed once and for all. But Jefferson's dinner table yielded enticing new paths for a man of his talents. By late fall of 1785, one of these had begun to take hold of him. It required little outside investment and promised great personal returns. It would also allow Ledyard to bank on the ethnographic and geographic knowledge he had acquired while sailing with Cook. He would become the first white American to explore the western expanse of North America.