Benjamin Franklin is known for being many things—an inventor, scientist, politician, ladies man, publisher, diplomat, and Founding Father. He also holds the distinction of being the first person to put into words the essence of the American dream.

The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin chronicles his attempt to forge a life and career in a strange new country. Franklin’s arrival in Philadelphia was less than auspicious. “I was dirty from my journey; my pockets were stuff'd out with shirts and stockings, and I knew no soul nor where to look for lodging. I was fatigued with travelling, rowing, and want of rest, I was very hungry; and my whole stock of cash consisted of a Dutch dollar, and about a shilling in copper,” he wrote.

After spending all of his money on three loaves of bread, Franklin has nothing left but his wits and ingenuity. What happens next has become part of our founding myth: Franklin becomes a printer, inventor, and statesman.

“Written into that story is the idea that you can make of yourself anything you will,” says Andrew Delbanco of Columbia University. “Nobody tells you what you’re going to be, who you’re going to be, or how you’re going to get there.” Franklin’s autobiography became the urtext for American dream stories. Writers who followed put their own stamp on the theme, but the idea that individuals decide their fates remains.

The way in which the American dream informs our culture is the subject of a new NEH-supported documentary, Novel Reflections . . . The American Dream , by Thirteen/WNET New York. The film was written and directed by Michael Epstein. It will air as part of the American Masters series on public television on April 4.

The film sprang from a desire on the part of Susan Lacy, the executive producer of American Masters, to find a creative way to present American fiction on the small screen. She gathered together major writers and literary scholars for a symposium and two key ideas emerged: Explore literature in a thematic way, which would allow film makers to tackle questions that matter to people, and move beyond the classics. “We decided that it was important to have a balance between the canon and new voices, which is a important part of American writing in the twentieth century,” says Lacy.

The film focuses on seven novels: Theodore Dreiser's Sister Carrie, Edith Wharton's The House of Mirth, F. Scott Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby, John Steinbeck's The Grapes of Wrath, Ann Petry's The Street, Gish Gen's Typical American, and Saul Bellow's Seize the Day. Not only do these novels portray the American dream, but they also depict a kaleidoscope of successes and failures. They also genuflect—either directly or indirectly—toward Franklin's autobiography.

Bringing fiction to film is not an easy task, particularly when you want to educate as well as entertain. “I knew early on that we did not want to license from Hollywood because more often than not those movies are not particularly accurate portraits—there is a lot of poetic license,” says Epstein. It also would have meant focusing solely on books that have received Hollywood treatments.

Lacy and Epstein also wanted viewers to hear the authors' own words. “It was important to us that people hear the art—they experience the book in some way,” says Epstein. They made the decision that when the books were read, it would be as if the authors were reading them.

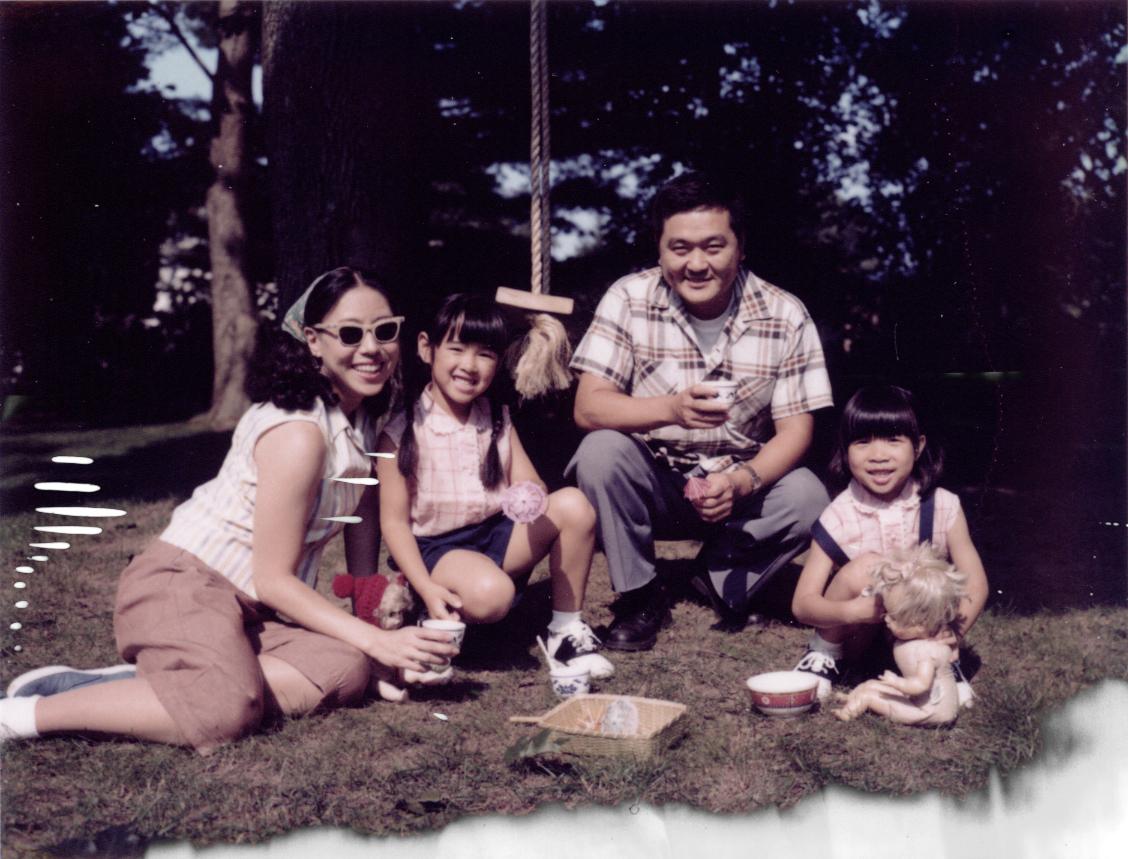

To accomplish their goal, Epstein had to devise a way for the viewers to hear the words, while providing a compelling visual component. He settled on using a technique that combines live footage with still photographs. As the novels progress by decade, the images evolve as well, providing the viewer with a visual history of the twentieth century. The House of Mirth is drenched in sepia tones with a nod to the style of cartes de visites, while Sister Carrie uses stereoscopic images. The Great Gatsby evokes a hand-painted postcard. The Grapes of Wrath takes its cue from the photography of Dorothea Lange and Walker Evans. Since its main character was a reporter, The Street mimics a newspaper in production. Typical American uses Polaroids and home movies to evoke the 1950s and 1960s. Seize the Day lent itself to a contemporary urban aesthetic. “It makes the show feel different from anything else that it out there and keeps it from being an English lesson,” says Epstein.

In addition to showing how key scenes in the novels critique the American dream, the film also tells the stories of the novelists themselves. Take, for example, Theodore Dreiser's Sister Carrie, which chronicles Carrie Meeber's attempt to escape restrictive small-town life. Lacking skills, Carrie finds it hard to find a job in Chicago. With few options, but many desires, she takes up with Charles Drouet, a traveling salesman who values money and luxury. Carrie naively accepts a loan from Drouet, failing to understand that he expects her to surrender to his overtures.

Carrie throws Drouet over in favor of George Hurstwood, a sophisticated older married man. After Hurstwood embezzles money from the social club he manages, the lovers first flee to Canada.

Unable to return to Chicago, the couple starts a new life in New York. Carrie becomes a Broadway star, but the disgraced Hurstwood cannot find a job. After Carrie leaves him, Hurstwood becomes destitute, finally taking his own life. “Literature was supposed to show us a world where self-discipline and virtue paid off and where duplicity was punished. And Dreiser just showed us the world as it is,” says Delbanco.

The plot of Sister Carrie sprang from the experiences of Dreiser's sister Emma, who had an affair with a married man. After Emma's lover embezzled money, they fled to Canada.

Carrie also stands in for Dreiser. In 1892, Dreiser abandoned his poor German immigrant upbringing in Terre Haute, Indiana, and moved to Chicago in search of a better life. Twenty-one years old with no money and no marketable skills, Dreiser suffered countless rejections until he found employment as a reporter. “There's no question that he is Carrie. What Carrie wants, what Carrie desires is what Dreiser wants, or wanted certainly when he was at Carrie's stage,” says Morris Dickstein of CUNY's Graduate School.

Sister Carrie and its brand of the American dream proved controversial. Dreiser sold the novel to Doubleday Publishing without the knowledge of its owner, Frank Doubleday. When Doubleday read the novel, he found Dreiser's failure to punish Carrie for losing her virtue repugnant and attempted to stop the book's publication. Doubleday's lawyers determined that he was obligated to publish but not to sell the book. He printed a few hundred copies, but refused to bind them. It wasn't until a later generation discovered the book that Sister Carrie became a classic.

F. Scott Fitzgerald, another great observer of American money, always thought himself the outsider. And like Dreiser, his feelings of inadequacy came through in this work. Fitzgerald grew up around money, but his family was not rich—he was the child of Irish-American immigrants and old American stock. “Dreiser was always an outsider, guessing about how the rich lived, and usually getting it wrong,”says Matthew Bruccoli. “Fitzgerald was a spy. He was the insider. Dreiser was outside mowing the lawn. Fitzgerald was in there taking notes.”

Fitzgerald fell hard for Zelda Sayre, a Southern belle. Sayre's family wasn't rich, but they had family and connections, which in the South was considered better than money. Fitzgerald wooed Zelda, but could not marry her because he was poor.

After failing at advertising in New York, Fitzgerald focused on reworking his rejected novel, This Side of Paradise. Published in 1920 by Charles Scribner's Sons, the era's premiere publishing house, the book sold more than forty thousand copies. Fitzgerald's newfound fame and prosperity allowed him to claim Zelda.

In many ways, The Great Gatsby is Fitzgerald posing the question: What if he had lost Zelda? Would money and fame have given him a second chance? Ten years after falling in love with Daisy and unable to marry her because he lacked money, the now-flush Gatsby attempts to reclaim her. “Gatsby imagines that because he now has money, he can rewrite the script according to his plans,” says critic James Atlas. He is no longer James Gatz, a blue- collar kid from Michigan, but Jay Gatsby, the scion of a wealthy midwestern family, who was educated at Oxford, lived like a prince in the capitals of Europe, and served with distinction in the Great War.

Daisy is initially impressed by the trappings of Gatsby's new life, but the illusion is shattered when she learns that Gatsby made his fortune selling liquor during Prohibition and has ties to the mob. Gatsby naively believed that he could buy access to moneyed society—and with it Daisy's love—but he failed to understand that how he made his money mattered. Not only does Daisy abandon him, but, in a case of mistaken identity, Gatsby is shot dead by the husband of Tom's mistress.

The Great Gatsby was published in 1927 at the height of Fitzgerald's fame. Audiences in the Roaring Twenties weren't ready for Fitzgerald's dark takes on wealth or the American dream. While the book received some good notices, sales were dismal. It would take the Great Depression and the Second World War before critics and readers recognized the novel's brilliance.

“Gatsby is one of the few books that you can read and reread,” says Atlas. “It has a tremendous freshness every time that you pick it up, because it's not about the plot. The plot is creaky and soon forgotten. You read it because it has this sense of pristine possibility. It's about life before it becomes mired and disillusioned.”

While Dreiser's Carrie worked her way to success and Fitzergerald's Gatsby fulfilled his dream only to find it flawed, Saul Bellow's Tommy Wilhelm has been a perpetual loser, whose life is riddled by self-defeating choices. Seize the Day follows Tommy for twenty-four hours as he grapples with the emptiness of his bank account and spirit. He is behind on his alimony and child support. He dwells on his failure to make it in Hollywood. What Tommy wants more than money is acceptance and a connection with his austere and financially savvy father.

“Seize the Day is about the tremendous pressure to achieve, the tremendous pressure to succeed,” says Atlas. Tommy's father became a success, but at the price of destroying his relationship with his son. Bellow imagines the American dream to be about more than material wealth; he wants it to include spiritual fulfillment.

Although the details of Tommy's life do not match Bellow's, his quarrel with society's definition of success reflected Bellow's own internal struggles. Despite finding success as a writer, Bellow struggled with the lack of resemblance between his life and that of his family. Bellow was the fourth and youngest child of Russian Jewish immigrants. His father and brothers were strong personalities, often bullying, who did well in business. For Bellow, a struggling writer who had trouble making the rent, they served as a reminder of his inadequacies.

“I think Bellow is trying to take the American success and failure novel to another level,” says Dickstein. “Tommy Wilhelm has absolutely reached bottom. He's wandering about, he's completely wiped out, he's been rejected by everyone. It seems like he's a natural candidate for suicide.”

Before Tommy can take such an extreme action, he stumbles into the funeral of someone he doesn't know. Overwhelmed, he begins to sob uncontrollably, giving release to all of his bottled up emotion, mourning what he has lost and the state of his life. The mourners mistakenly believe that Tommy cries for the deceased, provoking envy that anyone could feel so deeply for another. Atlas believes that Bellow's version of the American dream is “life rooted in spirit, rooted in our capacity to feel.” Success matters little unless you can give it a deeper, soulful meaning. Without it, the American dream is empty.

For more than two hundred years, the notion of making something of oneself, of becoming a somebody, has been woven into the American psyche. In each generation, novelists have put a different twist on the theme, and those twists have reflected the authors' times. While the accounts may be more sanguine than celebratory, the novels in the film show the extent to which the core message of Franklin's autobiography—that individuals make their own successes—has become essential to American identity.

UCLA professor Richard Yarborough suggests that the belief serves a function. “Every culture has its own way of encapsulating its wisdom. And American culture does so in a way that is almost akin to the way a religion works out its catechism,” says Yarborough. “I think all religions have a list of rules that you can follow, and I think the American dream from that standpoint is the secular religion.”