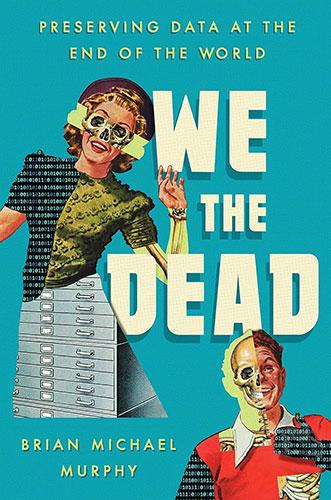

We the Dead: Preserving Data at the End of the World: An Interview with NEH Summer Stipend Recipient Brian Michael Murphy

Americans are unconsciously obsessed with media preservation. Think about the photos on your phone, the paper documents in your filing cabinet, the digital files on your computer. How did we get to be this way? In We the Dead: Preserving Data at the End of the World (University of North Carolina Press, 2022), NEH Summer Stipend recipient Brian Michael Murphy sets out to explain the emergence of the data complex in the early twentieth century and how it has continued to consume us. We are now perpetually entangled with data, which encompass every aspect of our lives––personal, social, financial, and even romantic. The data complex is both material and psychological, instilling in us a fear of the passage of time and the inevitability of decay. We the Dead follows American society at moments in history when we thought we were on the brink of the end of the world. Between libraries, data centers, time capsules, and even DNA storage, there is no shortage of ways in which we have tried to bombproof our data bodies and ensure that they live on, even after we are long gone. I recently caught up with Murphy to talk about his book, its inspiration, and the future of data preservation.

-

You consider yourself a media archaeologist. Could you discuss this emerging field and explain what drew you to pursue research in this area?

When I was 220 feet underground, looking at historical photos at the Corbis Film Preservation Facility, I realized that I wanted to write about not just the content of the photos, but everything I experienced there. From passing through a security checkpoint, where my car was searched by an armed guard within a cage of fencing, to sitting at a desk in a stone-walled cave that was formerly a limestone mine, to breathing in the frigid, reeking air of the vault where millions of old photos are preserved. The air smelled like the “vinegar syndrome,” which is the term for the chemical process that film undergoes as it decays. I wanted to write about photos as images, yes, but also as objects that had tactile qualities. Some of the photos were heavy, with thick stickers affixed to their backs from the days when they were licensed and circulated for reproduction in advertisements, magazine articles, and documentary footage. When the archivist would first bring them out of the vault, and for a while afterward, they were cold to the touch. They all smelled like decay.

Media archaeologists are often interested in the material aspects of media technologies and artifacts, and use a wide range of methods, from archival or scholarly research, to artistic practice and experimental performance, to some combination of any or all of the above. As I’ve made clear above, I am interested in the materiality of data, but for me that also includes the infrastructure that makes the preservation and circulation of data possible: tunnels, undersea cables, bunkers, railways, satellites, and the like. Ultimately, I think I was drawn to media archaeology because I was looking for tools I could use to describe what I was encountering in and around archives, some of which were housed in former ore mines, bombproof bunkers from the Cold War, abandoned nuclear missiles silos, and warehouses leftover from the natural ice trade.

-

What inspired you to undertake this project? You mention in the book that the research you conducted for your doctoral dissertation served as its basis, but what did your next few steps look like?

The digitization and preservation of the Bettmann Archive by Corbis—a company founded and solely owned by Bill Gates—really inspired this project. I wanted to understand why anyone would try to preserve anything for over 10,000 years, much less an archive of over 10 million fragile photos that were destined to decay within a century. By extension, I wanted to know how and why Americans became the most prolific preservers of data in the history of the world. All the existing explanations I found for why humans preserve were insufficient to explain why efforts to preserve intensify and expand where and when they do. So, I wrote a doctoral dissertation pursuing this question, and along the way I encountered fascinating, strange, and sometimes disturbing projects that preceded Bill Gates’s efforts to “permanently” preserve data, such as the Crypt of Civilization in Atlanta, Georgia, the Westinghouse Time Capsule of Cupaloy, the Eugenics Record Office in New York, and the Voyager Golden Record, which is now drifting through interstellar space on a NASA probe.

After completing my Ph.D., I continued to do research on the topics that were central to the dissertation, and in the several years after its completion, many new developments expanded the scope of my analysis. Jeff Bezos launched Blue Origin, and Elon Musk announced his ambitions for SpaceX to create a belt of thousands of satellites that would beam down WiFi all over the world, even as other venture capitalists announced plans to build data centers in outer space and mine asteroids for precious metals. DNA data storage became a more crowded field of investment, as did lab-grown meat and other realms of biofabrication. For All Moonkind set out to preserve Neil Armstrong’s bootprints and other historically significant human traces on the moon, which is where Arch Mission also planned to deposit a time capsule. So, I ended up writing additional chapters, and reshaped my existing manuscript to respond to all of this.

-

Among the many forms of and attempts at preservation that you discuss, is there a particular method or case study that you find most interesting or surprising?

The most surprising practice, one that persists into the present, is the use of etching in metal and other highly durable materials as a way to preserve data, even in, and especially in, moments when a new data format reaches the mainstream. In the 1930s, the creators of the first “permanent” time capsule, the Crypt of Civilization, used the newly popular medium of microfilm to preserve data, but also made stainless steel tickets for the opening ceremony of the Crypt in 8113. They intended for the tickets to be passed down through generations, from father to son, for the next several thousand years. Trevor Paglen micro-etched one hundred images onto a silicon disk and launched it into orbit on a satellite a little over a decade ago. A company called Milleniata even created a compact disc with a layer of synthetic rock embedded in it, so that the data could be written into a material that could be preserved for thousands of years. Of course, optical disc drives aren’t likely to be around thousands of years from now, so the data would be unreadable anyway. In many cases, such projects are based in a certain rationale, but not necessarily in rationality. New data formats are exciting, but not time-tested. Practices like etching, materials like metal and clay, are ancient methods of preserving data. Again and again, Americans have backed up data on “old” formats with artifacts on “new” formats, only to back up the “new” formats in ancient formats, a phenomenon I call a “backup loop.”

-

You note a common situation where Google’s algorithms miscategorized individuals based on their data, such as a female cell biologist being classified as an “old man” due to her research activities. What are the implications of our data bodies failing to fully represent who we are?

For me, one salient thing about that example, which is drawn from John Cheney-Lippold’s book We Are Data: Algorithms and the Making of Our Digital Selves, is that it reveals the power of data lying not necessarily in its accuracy, but in its currency. I don’t mean that data is the “new money” or the “new oil” or anything like that. Rather, I mean that data surveillance, the proliferation of data bodies, the aggregation, mining, and manipulation of data is fundamental to maintaining lopsided power structures in society, through which profits, freedom from legal consequences for one’s actions, and many other privileges flow upwards. The idea that big data verifies the reality of who one is—that is the powerful idea, the implication of which is that citizens are subject to the vagaries of the data body, which is cobbled together by institutions not fundamentally concerned with accuracy, or your rights, or your well-being, but with their own profits and power maintenance.

In some ways, what is happening now already happened a long time ago, when nation-states forced people to certify their identities through state-issued documents like passports and social security numbers. There are some excellent books on this, such as Sarah Igo’s The Known Citizen and Colin Koopman’s How We Became Our Data. The fact that humans today have to undergo an exercise wherein a machine requires you to “verify that you are human” in order to access your own bank account means that we have already lost the long-feared future war against the AI robots, a war we didn’t even know had already started. We’re still making and watching movies with this storyline, as if the defeat of humans by their own technology is something that might happen in the future.

-

The goal of preservation often inhibits present-day––and inevitably future––users from accessing archives, potentially rendering them almost useless. Is there a way we can meet present needs while ensuring long-term preservation?

I think we tend to drastically overestimate how interested future people will be in the mundane aspects of our contemporary existence. It is inevitable that artifacts will be lost, either through decay, use, misuse or abuse, loss of funding, natural disaster, or any number of other causes. While I understand that archivists have certain responsibilities that wouldn’t allow for such practices, I very much like the idea of using archival materials in experiments and performances. For instance, if there is an old film that can only be played once, that is so fragile that running it through the projector will make it unplayable in the future, why not play it that last time now? If you don’t play it, it’s going to decay anyway, unless you store it in a refrigerated facility for a long time, an energy-intensive method of preservation that will became decreasingly defensible amidst climate change, especially considering the fact that you’re preserving it only to not let anyone watch it. Every generation that comes along will be told what I have been told at archives before, namely, that I can’t watch the film because the archive has a responsibility to preserve it for future generations. But it’s just like that thing we used to say in elementary school to blow each others’ minds: “Tomorrow never comes, because as soon as tomorrow comes, it’s no longer tomorrow, it’s today.” Every future generation necessarily comes into existence as the current generation, and thus every one of them will be denied access to these materials when the time comes, because they are suddenly no longer the future people that we are preserving these things for. This endless loop will keep playing as long as we prioritize preserving for the future over access in the present.

What if, instead, that inaccessible, fragile film was played for one last time, and an audience attended the screening, and they were interviewed after, or invited to record in some way their experience, to process their emotional journey—the nostalgia, the joy, the guilt, the sadness, the excitement—whatever it is they felt as they watched, knowing that they were the last people who would ever see this film. It’s just an idea, a bit of a provocation perhaps, but it does embody in some ways a more sensible approach to materials than saving them forever, for a future day that is endlessly deferred, a day that never comes.

There is a vast realm of artwork that invites us to think differently about decay and the passage of time. Some of my favorite artists have done work in this vein, people who really helped inspire my thinking along these lines, such as the filmmaker Bill Morrison, and the photographer/architect Hiroshi Sugimoto.

-

You explore the twentieth-century concept of the “typical American family” and how data preservation has historically been used to reinforce a specific image of American culture that excludes minorities. One such example is the Westinghouse Time Capsule of Cupaloy, which produced a narrow version of American society aimed at promoting white solidarity. Do you believe it is possible to authentically showcase diversity through data preservation, or to preserve data without inherent biases or agendas?

Sure, preservation practices can showcase the diversity that typifies American life, and while any project has a certain set of assumptions underlying it, you can always do something much more interesting than simply try to reinforce the status quo or recuperate some nostalgic fantasy about your subject. The Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture is a great example of how to create exhibits and installations that both protect cultural treasures and still maximize their reach and impact on audiences. I visited that museum the year that it opened and thought it was stunning.

In the realm of digitization, I’ve long found the NEH-supported Photogrammar project to be inspiring. I actually learned about Photogrammar when I participated in a conference panel back in 2012, alongside Lauren Tilton and Taylor Arnold. I presented about Corbis and the digitization of the Bettmann Archive, and they laid out their preliminary work and long-term goals for Photogrammar, explaining how they created a publicly-accessible visualization platform and interactive map for digitized FSA and OWI photos from the 1930s and 40s. We were all still in graduate school at the time, so it was very bracing to talk with them and learn from them, and to see them doing work that was both preservative and generative in fresh and fascinating ways. It was also amazing to watch their project develop and expand into a really powerful resource over the decade that followed.

-

World War II and the Cold War strongly influenced the American fear of death, destruction, and the end of the world, resulting in substantial investments of time, money, and energy in trying to bombproof both our data and our minds. Yet, the only foreign aerial attack to have happened in the U.S. since then was 9/11, and we were totally unprepared. Can we ever achieve real security, or will the ever-expanding data complex hinder our ability to do so?

Total security is, of course, impossible, but many measures can be taken to make more people more safe for longer and longer periods of time. One version of security is to identify dangers and threats and try to eliminate them, or hermetically seal yourself and whomever you care about in a bunker, or hide behind a wall, or some other bulwark you can put your faith and trust in. Another is to try to address root causes of conflict, violence, and war. None of this is easy to do, and in my work, what I try to do is at least help us to see our situation as clearly as we can. It doesn’t help any of us to indulge in fantasies about “the cloud” protecting us or our data in ways that it simply cannot do, nor is it beneficial to pretend that certain kinds of security measures do not also simultaneously multiply our vulnerabilities.

Ultimately, the world can be a very scary place to live in, and each of us is going to have to choose how we want to respond to that. In We the Dead, I looked at some of the ways that Americans have tended to respond to threats, and examined the ways that decades of bombproofing and anxious safeguarding reshaped the physical, social, and emotional terrain of American life. Some of those threats were actual, some just perceived, but our frantic protective measures against them, in a very material way, made all of them real.

-

You are critical of the data complex while recognizing how deeply American society is intertwined with it, to the extent that human life and data are becoming irrevocably blurred. What was your experience researching and writing about a subject so troubling yet pervasive?

Researching and writing this book took over a decade, and I probably experienced just about every human emotion possible in the process. Some of the material I encountered was fascinating beyond anything I had ever seen, some of it devastatingly sad, while other material was downright goofy and hilarious. Novelists talk about how sometimes their characters take on a life of their own and start saying and doing things the novelist hadn’t planned for them. Nonfiction books about contemporary subjects can take on a similar life of their own, because the world is changing as you write about it. It simply will not hold still to pose for the portrait you’re painting! Sometimes, I had ridiculous thoughts like, “Hey, I didn’t give this tech billionaire permission to build an analog clock that will tick for 10,000 years and bury it inside a mountain in Texas and thereby force me to totally rethink the points I’m making in my latest draft of Chapter 4! Doesn’t he know that I have a book to finish?! That I have an argument to prove? And that I can’t revise this chapter again because I don’t have any more time to write today because I need to make lunch for my kids and take the dogs out and answer emails about meetings that have already happened, and meetings that will happen, and meetings that will never happen, and the dreaded meetings where we will do nothing but make a plan for another meeting? But now, I have to write about this eternal clock, and completely rearrange the chapter I thought I had just finished!”

In short, it was a very dynamic process, and sometimes it felt very heavy to sit with certain material for such a long time. But once I found the voice I wanted to use, the tones I wanted to strike in the narrative sections, the work felt very exciting in a profound way. And yet, each time I figured out how to inject my voice into a given section, I’d then realize I needed to rewrite fifty or sixty pages to make the voice and style match, and it would all feel very heavy again. I laugh out loud about it now, but it was pretty brutal to go through this cycle several times. I was excited when I finally figured out how to write the first few pages of the “Gas Chambers for Bookworms” chapter, and again when I was describing the setting for bomb tests at the Dugway Proving Grounds, only for months of very intensive work to follow those moments of exhilaration. Luckily, by the time I was writing about archives being deposited on the lunar surface and genetic engineers preserving data in synthetic DNA, I had become accustomed to writing with a consistent tone and with a certain pace, and so there was less editing to do along those lines in the last couple chapters of the book. But those first couple chapters were quite a task. I went through countless drafts.

-

Will it ever be possible to live without the data complex again? Is it something worth trying to resist?

It is certainly possible, and it is certain that the world will be arranged differently in the future. For better or worse, the world is always changing. As an artist and educator by vocation, I tend to ask questions, rather than promote sweeping political programs or grand utopian designs. So much of my work as a professor is about creating a generative structure for learning, and then inviting my students to decide what they think. Lately, I’ve wondered: what would happen if everyone, all at once, deleted their social media accounts? Would that be an example of a collective consumer choice that is also an instantaneous revolution? I’m not advocating for this, but it is an interesting thought experiment, isn’t it? In my view, truly critical thinking involves observing and reflecting on your automated and subconscious responses to things. How did you respond internally just now, when I brought up the possibility of collective social media deletion? Did a voice in your head say, without thinking, “That could never happen,” or “I could never do that”? Why couldn’t it happen? Are you, are we, really that unfree?

As far as the data complex goes, it will likely persist as long as we continue to feed it the data of our daily lives through the platforms, apps, and tracking devices we choose to use, as long as we carry them, attach them to, or even implant them into, our biological bodies. In my teaching and writing, I try to help people see the choices available to them, the ones they have made, the ones they are currently making (whether they realize it or not), and the ones that become possible by thinking and living in a new way. There is an art to being a free citizen, and, like all arts, freedom is a practice comprised of choices. But it is the student’s or reader’s job to choose whether they want to participate in or resist something. I just try to paint as clear and memorable a picture as I can and offer that picture as something that might enrich their thinking and feeling and inform their choices. I also often try to make them laugh. I don’t know how to do the work I do without it also involving laughter.

-

You speculate on it in your book’s conclusion, but what do you envision for the future of data preservation? Are there any hopes or desires you hold personally?

It is possible that DNA data storage will scale, which could result in a seismic shift in possibilities for both data density and more or less permanent preservation. Personally, I like to try to find small ways to reduce the amount of time I spend looking at a screen. I don’t have an adamant moral position against technology, but I have simply found that I “like” my life better when I’m less “connected” (to snarkily use the parlance of digital ideology). I do not have any social media accounts, and I like the idea of building my life in a way that I will eventually be able to choose how much or how little involvement I have with the digital world. Imagine that... having a choice in the matter.

-

What’s next for you and your work?

I’m working on several essays, and I just finished co-editing a themed folio on “Writing From Rural Spaces” for the Fall 2024 issue of the Kenyon Review. It was an honor (and a lot of fun) to work alongside co-editors Jamie Lyn Smith and Andrew Grace (who also happens to be my favorite poet), and the entire team at KR. The pieces in the folio are incredible, and I’m really excited and grateful that so many deeply gifted writers sent their work our way.

In terms of ongoing and future projects, I recently wrote a novel called Bright Bridge, and have reached out to several literary agents who I think could be a good fit for it. The story is set in an alternate history, in the year 1999, and explores racial stereotypes, AI, broken relationships, and death. It’s a comedy.

Brian Michael Murphy is an associate professor of American Studies at Williams College and a faculty associate at the Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society at Harvard University. His work has been featured in the Wall Street Journal and the Kenyon Review, among other places, and We the Dead was awarded the Lois P. Rudnick Book Prize from the New England American Studies Association. Murphy received an NEH Summer Stipends Award (FT-270775-20) in 2020 to support the writing of We the Dead: Preserving Data at the End of the World (University of North Carolina Press, 2022).

The Summer Stipends program supports continuous full-time work on a humanities project for a period of two consecutive months, stimulating new research in the humanities and its publication. For more information on the NEH Summer Stipends program, or to apply, see the program’s resource page. Contact @email with questions.