It was 1898 and the port city of Wilmington, North Carolina, was bustling with former slaves. They competed with white citizens for jobs as blacksmiths and carpenters, doctors and lawyers. The city's population was majority Black citizens, and their wealth and influence were growing. They bought property and opened businesses, invested in banks and worked as police officers. They held jobs in government, won election to public office—including to the U.S. House of Representatives—and organized alongside their working-class white neighbors to create a political movement known as Fusion, in which white Populists and Black and white Republicans formed joint electoral tickets on shared priorities. Black men served on the Board of Aldermen, as city treasurer, city jailer, and city coroner. Ten of Wilmington’s 26 policemen were Black.

But Black men’s success threatened the power of the local white elite, so white men mounted the first successful coup d’état in U.S. history, wielding intimidation, racist propaganda, beatings, and murder to drive Black people out of office, out of business, and out of town. An unknown number were murdered during what is now called the 1898 Wilmington massacre, a series of terrible events that would leave the city forever changed.

The beginnings of the coup can be traced to the summer of 1898. Self-declared white supremacists used the state’s most influential newspaper, the News & Observer, published by Josephus Daniels, to gin up panic over “Negro Rule,” with inflammatory headlines and racist cartoons depicting Black people as buffoonishly incompetent when they weren’t chasing down and raping white women.

Before the coup was in motion, however, a racial panic was already underway. Earlier that year, Rebecca Felton, a white woman from Georgia, gave a speech claiming that white men weren’t doing enough to stop the "Black beast rapist.”

“Where there is not enough religion in the pulpit to organize a crusade against sin, nor justice in the courthouse to promptly punish crime, nor manhood enough in the nation to put a sheltering arm about innocence and virtue,” she said, “if it needs lynching to protect women’s dearest possession from ravening human beasts, then I say lynch—a thousand times a week if necessary!”

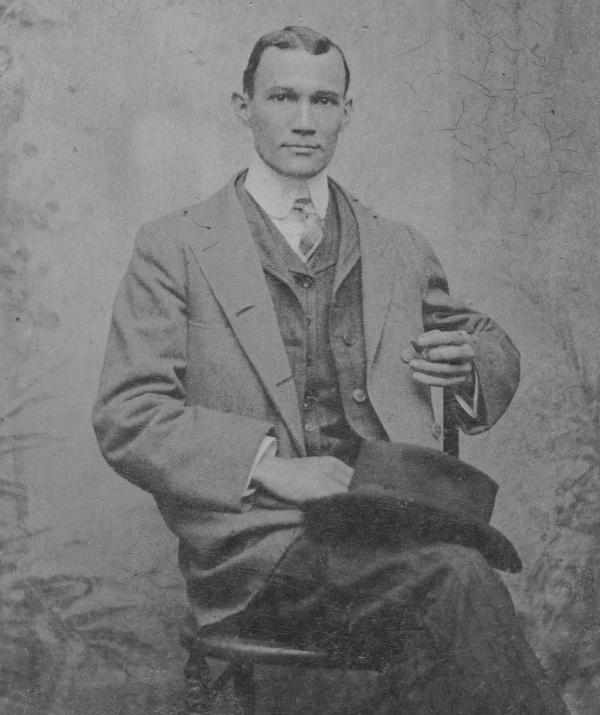

White supremacist newspapers reprinted the speech, and Alex Manly, editor and publisher of the Daily Record, Wilmington’s Black newspaper, had the temerity to respond that, indeed, the white men who had been raping Black women since the country was founded had not been held to account. His editorial was reprinted throughout the South, further enraging the white elite, and threats against Manly’s life poured in.

Wilmington’s white business leaders, aided by the News & Observer, amped up their white supremacist campaign. They hoarded guns and cheered barn-burning calls to action. They invited help from South Carolina racists—the so-called Red Shirts, white men who would yank Black men out of their homes, beat them, and threaten to kill them if they tried to vote. On November 7, at the county courthouse, Confederate Civil War veteran Alfred Moore Waddell gave an incendiary speech: “Men, the crisis is upon us. You must do your duty. This city, county, and state shall be rid of negro domination once and forever. You are the sons of noble ancestry. You are Anglo-Saxons. Go to the polls tomorrow and if you find a negro out voting, tell him to leave the polls. And if he refuses, kill him. Shoot him down in his tracks.”

On Election Day, armed white men (Red shirts) stalked the streets of Wilmington, intimidating Black men from voting. In Black precincts, election officials threw out Republican ballots and replaced them with Democratic ones.

As publisher Daniels wrote in his memoir, Editor in Politics, “If you have never seen three hundred redshirted men towards sunset with the sky red, you cannot concede what an impression it makes. Their appearance was the signal for the negroes to get out of the way. The result, of course, was that many negroes either did not vote or made no fight in the affected counties on Election Day.”

The intimidation and fraudulent votes ensured a Democratic victory in North Carolina, but white supremacists in Wilmington were not content to stop there. The morning after the election, hundreds of white leaders formed a plan to force out the city’s Fusionist mayor and Black municipal officeholders. They issued a White Declaration of Independence, proclaiming that they’d never again be ruled by men of African origin. A committee led by Waddell came up with a list of demands, including the closure of the Daily Record, and ordered the city’s Black leaders to respond.

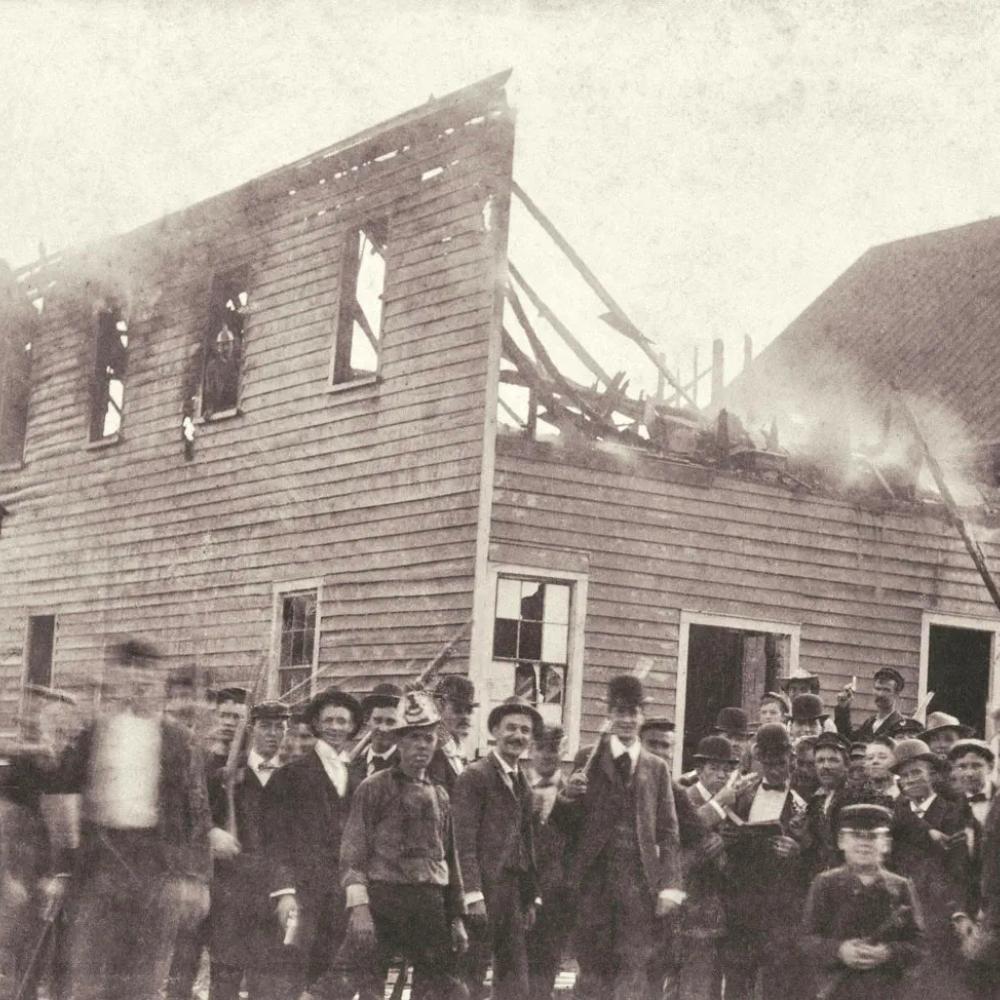

Vigilantes rode off to find Manly and lynch him. After he escaped, a mob burned down the offices of the Daily Record and then posed for triumphant photos in front of the smoldering remains.

The mob forced their way into Black churches and a community center. They killed Black men and forced women and children to hide in the cemetery and the swamps. They held local government officials at gunpoint until they resigned their seats and ran prominent Black families out of town. At the time, 56 percent of Wilmington was Black. Today its Black population is just shy of 14.9 percent.

And the story was nearly erased from history. Newspaper headlines at the time referred to it as a Black uprising, as if the Black people were at fault. It wasn’t until the 1950s that it was recognized as a massacre, and not until 100 years after it happened that it was recognized as an insurrection, a coup, with distorted media one of the elite's weapons.

Today the story is told in American Coup: Wilmington 1898, running now as part of American Experience on PBS and sponsored by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities in association with PBS North Carolina. Directed by Brad Lichtenstein and Yoruba Richen, it weaves the history of the coup with the experiences of descendants of both the attackers and their victims, some of whom were talking about their family’s role on camera for the first time.

“American Coup: Wilmington 1898 is a cautionary tale for our country,” said PBS North Carolina executive producer Rachel Raney, “about a perilous breakdown of a cornerstone of our democracy: fair and free elections.”

The filmmakers found many of the descendants through the Wilmington chapter of Coming to the Table, a national organization dedicated to facilitating community discussions about racial violence. Now, people like Lucy McCauley, a great granddaughter of William McKoy, a white man who helped orchestrate the coup, sit down with Kieran Haile, a descendant of newspaper owner Alexander Manly, to bring their ancestors’ experiences to light.

“I didn't know about it, like everybody else in Wilmington, for a very long time,” McCauley says in the film. “When I was growing up here, in high school and even into college, I was drinking the Kool-Aid. I learned all this about my great-grandfather in 2018, and it was just a physical blow to my body. ’Cause it was such a departure from everything I’d been told about my family and everything I had believed.”

The great grandson of Josephus Daniels says, “The News and Observer did so many terrible things back in that period of time. We have had a reckoning with ourselves about, you know, who Josephus was. In his later years, he was unapologetic. It's a shame that he did not recognize that the things that he did had damaged our state and our nation. I can't apologize for him, but, you know, I feel remorse. Part of the legacy that I have is that we were the worst of it for a period of time.”

The story was buried because of shame among the white families, but the families of Wilmington’s Black citizens also considered the topic taboo. Too painful. Too much betrayal.

“My dad and his siblings, they were all of the stance, uh, do not go back to Wilmington, just leave it alone and move forward,” Haile says in the film. “They were still running. They were still trying to survive.”

Bridging that gap, bringing the truth out into the open, and finding ways to heal are all potential offshoots from the film, much of it filmed in the historic buildings where the coup was planned and the defense discussed. The screening of the film was held in Thalian Hall, the same place where white supremacist Waddell called for violence against Blacks for exercising their right to vote. While the city still suffers inequality, the hall was packed with people of all races. PBS North Carolina is working to get the story of the coup incorporated into textbooks and classroom lessons, so the next generation won’t forget this history. Remembering is a path to reconciliation.

“The lesson in all this stuff—South Africa maybe being the preeminent example—is that it’s hard to do until you kind of cross over that threshold,” says film director Lichtenstein. “And then the impact on yourself and the impact on the community, large or small, however you define it, is so profound that for most people it becomes very much worth it. At a really deep level.”