The basic give and take of translation seems simple enough. A work written in one language is translated into a second language. But it doesn’t always happen that way.

Sometimes a work is translated from a second language into a third by a translator who doesn’t build from the original work. Instead, he or she works off the second language and produces a translation of a translation. In such cases, the second language, into which the work has already been translated, is called the relay language.

So did many works of Russian literature come to be translated into Korean—via the intermediate language of Japanese. Just as in a relay race, in which a baton is passed from one runner to the next, Japanese passed the baton—linguistically speaking—of Russian literature in translation to Koreans, allowing them to swiftly adapt Russian novels and essays to their own developing and distinct national literature.

Many of Korea’s intellectuals traveled to Japan to study for a time, especially from around 1905 through the 1920s. They pored over texts in Japanese, sitting shoulder to shoulder with their Japanese counterparts at colleges and universities in Tokyo and grappling with the same literary works. Many new ideas were streaming into Japan, especially from Russia, whose writers the Japanese greatly admired. Knowing little Russian, the Koreans read Russian authors in Japanese translations and translated them from Japanese into Korean.

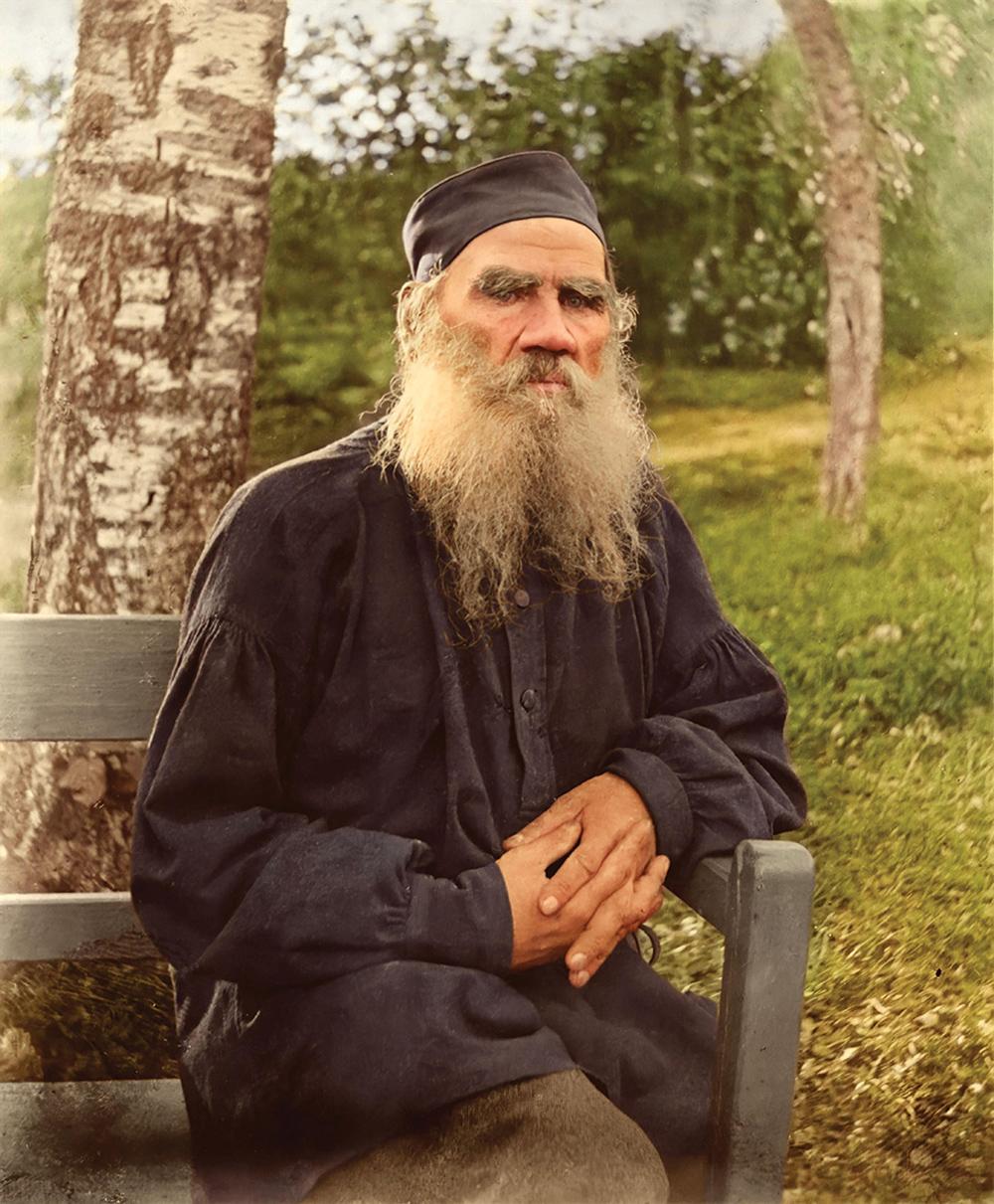

A short story by Anton Chekhov, “Sleepy,” caught the interest of the Japanese and had an impact on the Koreans at a critical juncture, as girls in their country were still being married off at a young age. Some of the child brides in Korea, according to contemporary newspaper accounts, reacted violently to their circumstances, burning down their houses while their husbands slept inside. In “Sleepy,” the protagonist, a thirteen-year-old servant girl who is sleep deprived, strangles the baby of the couple forcing her to work long hours. The two realities—child labor and children being married off—mirrored each other and cried out for reform. “Sleepy” and other stories by Chekhov came to be published in Korean. Additionally, Leo Tolstoy’s essay “What Is Art?” weighed heavily in how Korean artists and intellectuals began thinking about the role of literature in society after Koreans translated, sometimes adapted, this and other works of Russian literature from Japanese into Korean. Heekyoung Cho, in the NEH-funded Translation’s Forgotten History, meticulously studies the currents and crosscurrents of this cultural phenomenon and how it helped form Korean national literature.

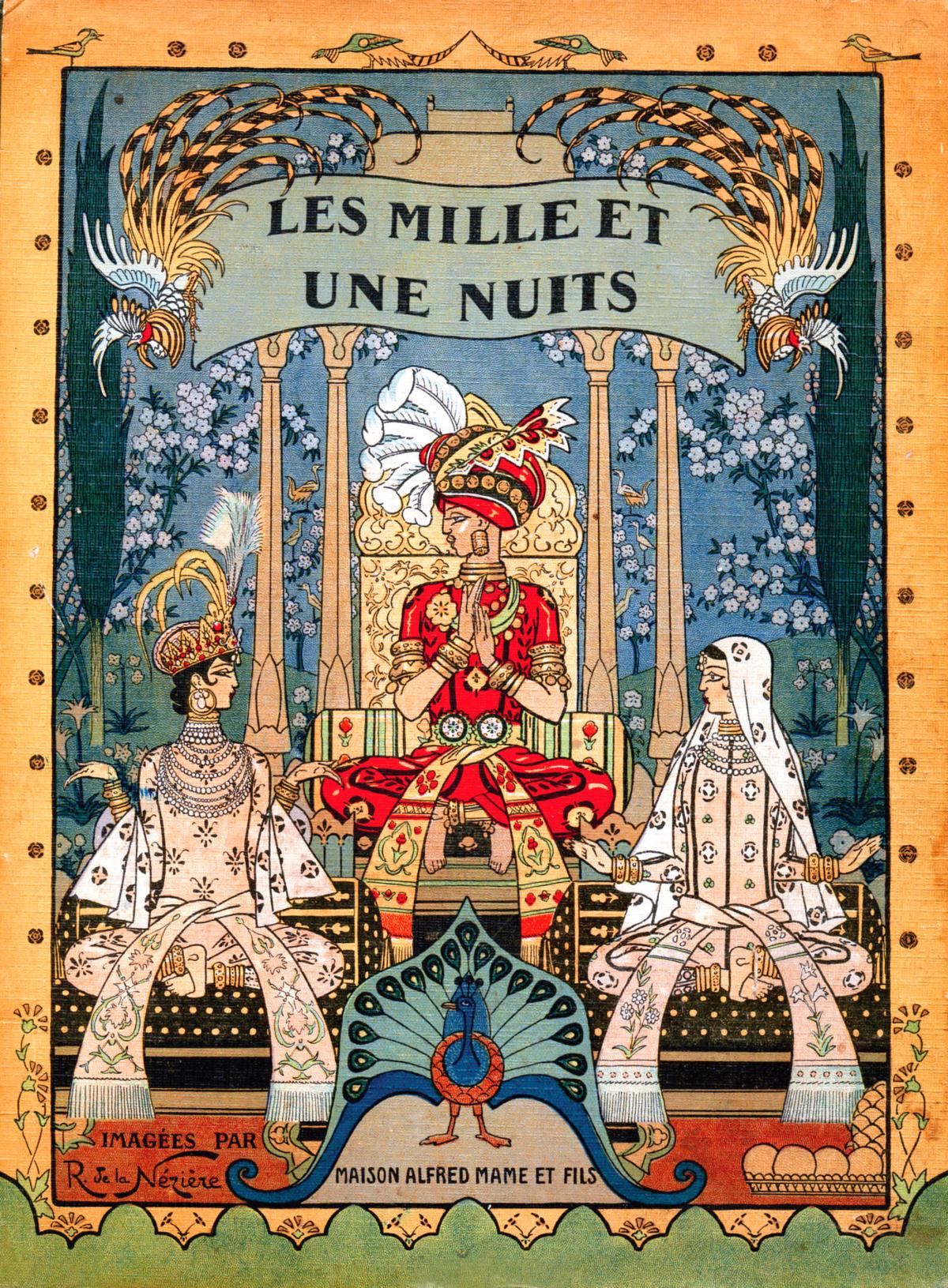

In the world of translation, relay translations often occur when neither the source language nor the target language is dominant. The relay language, the go-between, is dominant. An example is illustrated by the first translation of One Thousand and One Nights into Russian. Few Russians could translate Arabic in the eighteenth century, while the French had the noted classics scholar and orientalist Antoine Galland, whose translations of the work were published between 1704 and 1717. About 50 years later, Russian Alexey Filatyev translated One Thousand and One Nights from French (the relay language) into Russian.

By the late nineteenth century, Japanese intellectuals became engrossed with what they regarded as fresh ways, in Russia, of writing about traditional subjects. At a time when peasant unrest was simmering in Korea, Ivan Turgenev’s A Hunter’s Sketches interested both the Japanese and, especially, the Koreans for its part in abolishing serfdom. The Koreans’ familiarity with and passion for Russian literature far outstripped their interest in English and French literature and other literary traditions in the West. Fyodor Dostoevsky, for example, came to be viewed by some Koreans as a “resistant intellectual” or sympathizer of peasants and workers. His writings provided food for thought and concrete examples of ways to address social ills at home in Korea. For their part, the Japanese had become especially interested in the nihilism of Turgenev in Fathers and Sons. The Koreans, however, did not always respond to the Russians in the same ways the Japanese did. They took the messages coming to them from Russian literature, interpreted them according to their own social circumstances, and translated the Russians into Korean, using the Japanese language as a go-between and filter but not hewing at all times to the same specific Japanese take on the Russians.

Turgenev ignited great interest among the Koreans with his 1859 novel, On the Eve, which was translated three times (once as a play, once as a full-length novel, and once as a short story) from Japanese to Korean during the colonial period of Japanese annexation, 1910 to 1945. On the Eve concerns a Bulgarian revolutionary and a Russian woman who admires him and decides to take up the cause. One Korean adaptation of a Japanese translation has the woman, Elana, follow the man, Dmitri, from Russia to Bulgaria and become more politically involved than in Turgenev’s original. Another Korean produced a summarized translation of On the Eve, reducing Turgenev’s novel to eight pages, which avoided political zeal and concentrated rather on the relationship between the man and the woman. Another translation, published in 1924, was a faithful rendering. The three examples demonstrate the array of translations coming onto the scene from Korean writers and translators at the time—adaptive in one case to underscore a desired value in a main character, summary in another case to excise vast passages considered to be of marginal interest, and, in another case, faithful, respecting the integrity of the original.

Literary traditions in Japanese stretched back many centuries and encompassed many ideas, forms, and genres, both new and old, that developed on their own in Japan and came later from Chinese literature. Japan possessed a mature national literature, while late in the nineteenth and early in the twentieth century Korea did not. As a protectorate, Korea had been under the heel, culturally, of China for centuries. The Korean language was perceived by Korea’s own elites as inadequate for original literary work. Translation itself, though, had been, since the mid fifteenth century, an evolving genre in Korea, where it was regarded as highly as original work. Consequently, when Korean writers began translating Russian authors from Japanese, they easily adapted these works to their own circumstances as the country developed its own sense of a national literature. Translations, especially ones serving as adaptations rather than literal renderings, became a way of introducing new modes for broaching traditional subjects such as love, romance, and emotion, and as a way of examining entrenched cultural practices, such as early marriage, both for girls and for boys. Korean writers and translators were keenly aware of currents of world literature at the time, as they were translating other literatures and acquiring a sense of their own literary tradition.

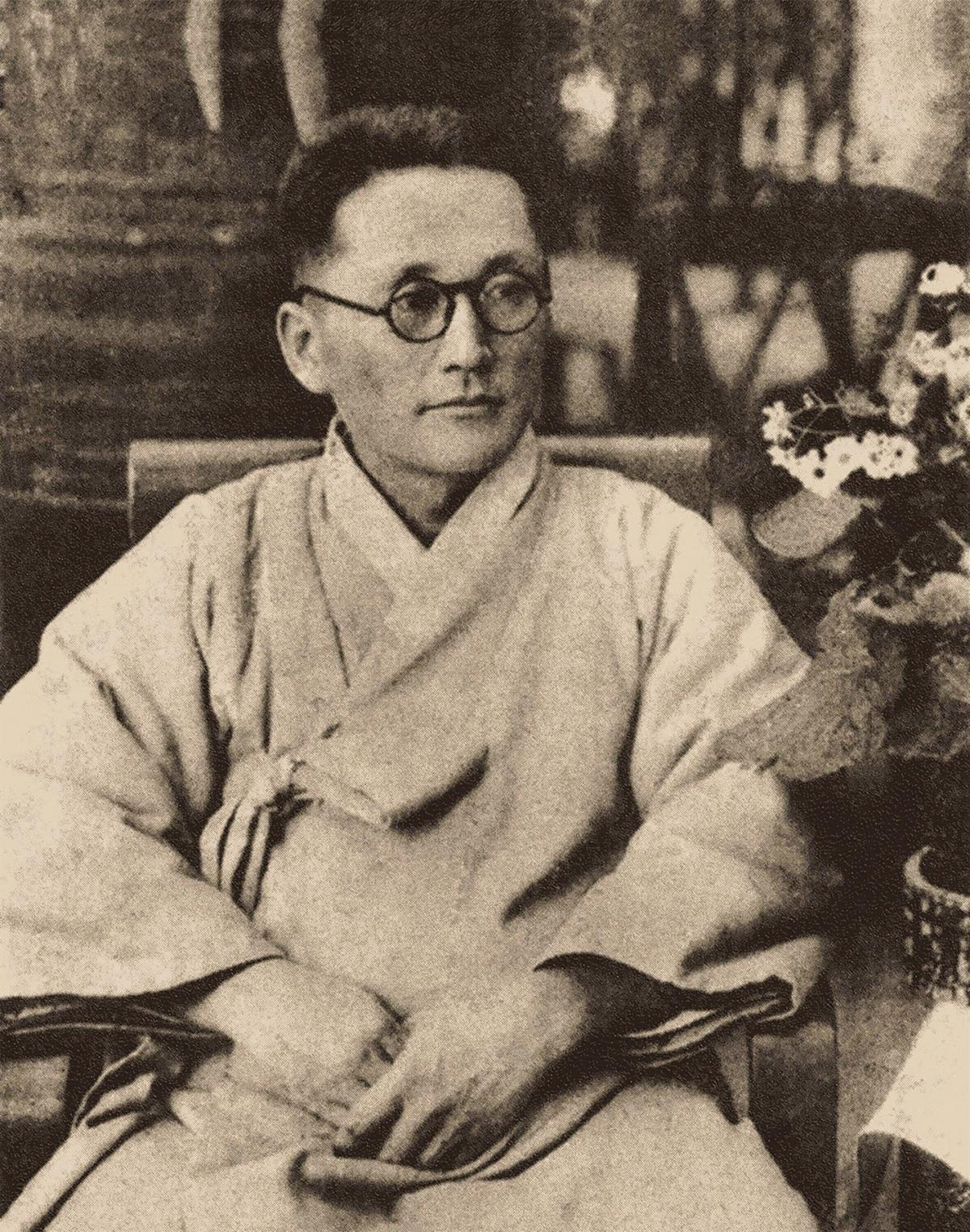

Yi Kwang-su, a writer credited with authoring the first modern Korean novel, The Heartless, was born in 1892 in what is now North Korea, and was sent to Japan in 1905 to study. Sojourning back to Korea by 1913 for a brief teaching stint, he was struck by the segregation of Korean and Japanese train passengers. This was shortly after the Japan-Korea Annexation treaty, when Japan gained control of newspapers, administrative and economic reforms, and the gendarmerie, police, and military. Yi went to Japan again in 1915 and studied in Tokyo in the liberal arts division of Waseda University, which was becoming a mecca for the study of foreign languages and literatures. Waseda had a department of Russian literature. In his second year at the progressive institution, Yi began writing The Heartless. Eventually, Yi went back to China in 1919 (he had lived in Shanghai in 1914) and became involved in protests against Japan’s annexation of his homeland. His life took another, unexpected, turn later, back in Korea, as he came to be seen as a collaborationist with the Japanese. Estimations of his contributions to Korean national literature, however, remain intact.

The Heartless was on the vanguard of Korea’s national literary awakening. Yi wrote in Korean vernacular and created a tone of moderate politeness between his characters. He was an early proponent of relatively informal modes of address among people of different social rank. At the same time, he promoted the idea that Korean was an artful language and worthy of poets, novelists, and essayists. In one compelling passage, an anxious young woman is on her way to visit the home of her future husband to meet his relatives. As she arrives at the house, she notices the family name inscribed on the gate and thinks how beautiful the characters look. Yi, profoundly moved by Tolstoy’s “What Is Art?”, downplayed the Russian novelist’s ideas on universal Christianity and emphasized instead his stance on the power of art and literature to transmit the feelings and emotions of an artist or novelist to a viewer or reader—an idea that proved influential in Korean literature. For Yi, as for Tolstoy, emotion in a work of literature was paramount.

Yi was a towering figure in the development of Korean literature in the early twentieth century, but he stood among dozens of other men and women writers who contributed mightily to this development. Women writers, due to the Confucian hierarchies set in place by the Chinese, composed their works primarily within the household and came onto the literary scene later than men. Among the men writing and publishing at the time was poet Kim Ki-jin (1897–1926), who also studied at Waseda University and came to regard the social realist Turgenev as the most important Russian writer for Koreans. Kim greatly influenced Pak Yǒng-hǔi, (b. 1901) a writer who argued for a national literature that addressed social problems, especially the plight of workers. For both of these Korean writers, the Russian Revolution had a huge impact, and both men became devotees of what they saw as Russian materialism. In the broadest sense of translation, then, Korean writers were recognizing parallels between realities in their own country and those described in the literature of both czarist and revolutionary Russia and rendering impressions of these parallels into their own nascent national literature and literary criticism.

Newspaper readership was increasingly important in Korea, making newspapers a valuable platform for essays by writers such as Kim and Pak as well as fiction, including translations of Russian literature, published in installments. Original literature modeled on Russian works also appeared in the newspapers, sometimes with standard plot lines that hearkened back to Korea’s fin-de-siècle literary roots, often presenting characters expressing emotion in more overt ways than previously, as is the case in The Heartless. This decades-long process had been made possible by the ongoing influx of adaptive translations of Russian authors by way of Japanese translations.

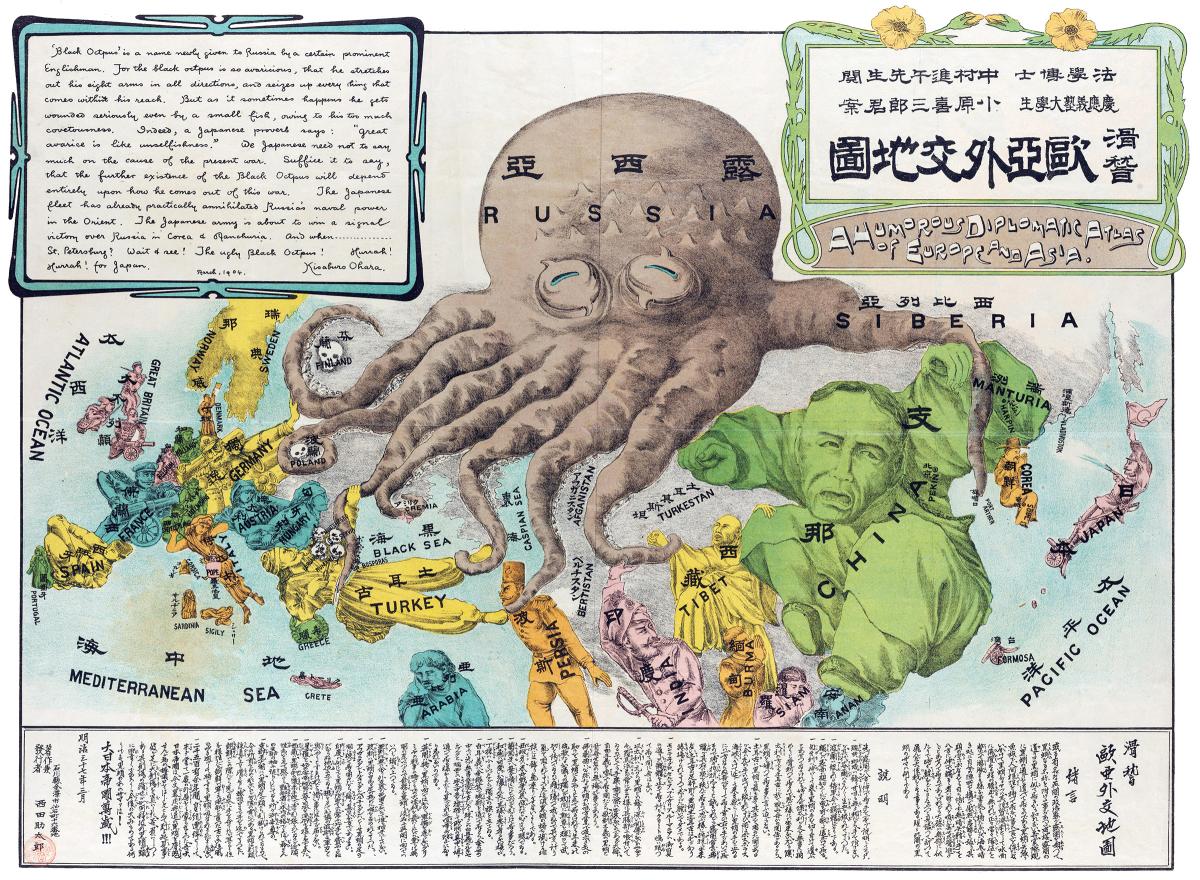

Koreans began translating literature from Japanese in earnest starting in 1900, and the activity continued into the 1920s. One reason for Korea’s interest in Russian literature was proximity. Russia was a regional power, and conflicts such as the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–1905 brought Korea into closer contact with Russia. The reasons both the Japanese and the Koreans were especially sympathetic to Russian literature had much to do, too, with the regulation of political speech in czarist Russia, a rapidly modernizing Japan, and a cultural awakening in colonial Korea. In all three countries literature took on the role of freely expressing, or attempting to express, the hopes and desires of their peoples, or, as Tolstoy would have it, their emotions. It is a well-worn cliché to refer to translators as couriers of culture. Early twentieth-century translators in Japan and Korea, however, not only met that responsibility but raised the bar and, in Korea’s case, created the foundations of a national literature.