“I love to see leaves blowing through the headlights. I don’t know why. I mean they’re just dead leaves, no good for anything, but I love to see them blowing through the light.” —Bullet Park

With a name like John Cheever—pronounced “John Chee-vah,” if you prefer—you would have assumed that he had attended Harvard or Yale or at least Babson, Hamilton, or Kenyon.

Yet facts are facts: The author of the classic novels The Wapshot Chronicle (1957), Bullet Park (1969), and Falconer (1977), as well as a heaping of the past century’s best-remembered short stories, was not a product of the Ivy League, or even the sub-Ivy League. In fact, despite his WASPy surname, refined manners, and tweed-jacket-and-knitted-tie style of dress—all of which might suggest an auspicious college career full of fraternity parties and not-too-strenuous intramural sports—John Cheever never made it further than high school.

In the autumn of 1981, appearing on The Dick Cavett Show alongside his genteel colleague, unofficial mentee, and all-around idolater John Updike (Harvard ’54), host Cavett (Yale ’58) had the impudence to raise this most unexpected bit of biographical trivia. “One of you went to college and the other didn’t,” Cavett said, his head turned upward and away from his possibly embarrassed guests. “Does that make either of you a better writer in any way?”

After a brief silence, Updike quickly mumbled something about whether the audience should guess which one of the two had partaken in higher education. Then Cheever, gamely defusing the tension, interjected. “John—obviously, conspicuously—enjoyed the benefits of an education,” Cheever said. “I lack them.” Going further, Cheever proceeded to link Updike’s considerable acumen as a critic with his college training. Possibly embarrassed, Updike shrugged off Cheever’s compliment and tried his best—the old college try, we might say—to return serve: “You are a very learned, actually, fellow in my book,” Updike told Cheever, who was nearly twenty years his senior and was dead the following year. Cheever did not acknowledge the sincere but awkward compliment.

Well, what are we to take from this exchange between two twentieth-century literary titans about their respective levels of educational attainment? Did Cheever covet Updike’s book-reviewing assignments? Did Updike resent that he had to study that which Cheever seemingly arrived at without effort? Perhaps the most pertinent point to be made is that Cheever, for all of his interest in and affection for the American upper-middle class, was actually an outsider with the breeding of an insider—a writer who was compelled to peek into the finest homes, toniest country clubs, and stateliest swimming pools but who resisted full initiation into the ranks of the well to do.

For Cheever, who was born in 1912 in Quincy, Massachusetts, alienation was no affectation. The much younger of two boys born to Frederick and Mary Cheever, John was led to believe that his arrival had been a matter of happenstance and considerable regret. In his great short story “The Housebreaker of Shady Hill” (1956), Cheever bestows his own profoundly unhappy origin story on his protagonist, Johnny Hake: “I was thinking sadly about my beginnings—about how I was made by a riggish couple in a midtown hotel after a six-course dinner with wines, and my mother had told me so many times that if she hadn’t drunk so many Old-Fashioneds before that famous dinner I would still be unborn on a star.”

For their part, Cheever’s parents were too preoccupied with salvaging their own rapidly diminishing social standing to compensate for their second son’s knowledge that he was unwanted: Frederick Cheever was an early casualty of the coming Great Depression, losing his source of income in the shoe trade (whether Frederick was a mere shoe salesman or the owner of a shoe factory has been called into question) and, simultaneously, acquiring the same excessive taste for alcohol that would later plague his last born. “He applied for dozens of jobs, but nothing worked out,” wrote Scott Donaldson about Frederick in John Cheever: A Biography. “Perhaps he aimed too high. He must have felt it was too late to start over.”

With the fate of the family now in her hands, Mary Cheever tapped into her inner entrepreneur to open a small retail establishment, the Mary Cheever Gift Shoppe. Yet Mary’s determination to keep her brood afloat went heartlessly unappreciated by her younger son, who took his mother’s transformation into a merchant not only as an affront to his flailing father but as an assault to the fabric of family life. “He spent many an adolescent afternoon amid the clutter and debris in the back of her shop, waiting for his mother to close up,” Donaldson wrote. “At Christmastime especially, she devoted her energies to the gift shop and not the home. John knew that it had to be that way, and resented it.” His mother was just the first woman named Mary to disappoint and puzzle him.

Following three years of poor to middling grades, Cheever was booted from Thayer Academy in Braintree, Massachusetts. (Cheever claimed his expulsion resulted from smoking cigarettes.) Applying some of the same lemonade-from-lemons industriousness of his mother, though, he turned this reversal into the stuff of fiction, whipping up a story titled “Expelled.” Famed editor Malcolm Cowley judged it worthy of publication in the New Republic—Cheever's first sale as a writer. “John was such a naturally talented writer that all he needed was a little direction and a little time,” the editor said in the book Conversations with Malcolm Cowley. “Someone was bound to recognize that he was born a writer.”

Indeed, Cheever grasped early on that he had lucked into a winning combination: His rarefied but troubled milieu (the too-proud father, the phlegmatic mother, the fancy school that had had enough of him) would furnish him with enough rich and strange material for a lifetime, while the slings and arrows of his youth—the loneliness he felt as an unplanned child, the pity he felt for his father’s straitened circumstances, the scorn he felt for his mother’s shopkeeping—left him with striking reserves of empathy and great powers of observation. No one else has written about blue bloods with such microscopic perception.

“I was born into no true class, and it was my decision, early in life, to insinuate myself into the middle class, like a spy, so that I would have an advantageous position of attack, but I seem now and then to have forgotten my mission and to have taken my disguises too seriously,” Cheever confessed in a 1948 entry collected in the brilliant, forbiddingly comprehensive Journals of John Cheever, which was posthumously published, amid much hue and cry, in 1991.

The push-pull of spying on others while simultaneously wishing to belong to their set informs much of Cheever’s fiction, which, starting in 1935, began appearing in the New Yorker, whose fiction pages he helped shape as surely as John O’Hara once had. In “The Enormous Radio” (1947)—collected, like most of his great stories, in that famous, red-jacketed volume The Stories of John Cheever (1978)—married apartment-dwellers Jim and Irene Westcott acquire an ungainly radio encased in gumwood with the simple notion of satiating their taste for classical music. Upon turning the beastly device on, however, the couple discovers that it can transmit the behind-closed-door conversations of their fellow residents. Jim and Irene take to eavesdropping. After several sessions of listening to the radio, Irene runs into some neighbors on an elevator—all made-up and ready to face the world. But Irene knew secrets: “Which one of them had been to Sea Island? she wondered. Which one had overdrawn her bank account?” Cheever so acutely expresses Irene’s urge to listen—as well as her curiosity about matching overheard conversations with actual people—because they are impulses he shares.

In “The Housebreaker of Shady Hill”—another tale of breaking and entering, this time physical rather than auditory—relatively low-on-the-food-chain executive Johnny Hake is outraged at having to inform an older coworker that he has been sacked. Cheever, who is always attuned to scenes of embarrassment, beautifully establishes the pending doom as Johnny arrives at his colleague’s apartment to deliver the verbal pink slip: “The storm was about to break now, and everything stood in a gentle half darkness so much like dawn that it seemed as if we should be sleeping and dreaming, and not bringing one another bad news.” In the course of the story, Johnny goes into business for himself, but, with money woes and a sense of desperation building, he works himself up to burglarizing the home of a super-rich couple, the Warburtons. Under the cover of night, Johnny plucks a wallet from the coat of a snoozing Mr. Warburton, but the theft invites self-hatred—as though the very act itself, rather than whatever minuscule harm it causes, obviates all traces of decency from Johnny’s past. “Oh, I never knew that a man could be so miserable and that the mind could open up so many chambers and fill them with self-reproach! Where were the trout streams of my youth, and other innocent pleasures?” In the final pages, Johnny’s fortunes miraculously are reversed and all is set right in Shady Hill, including missing wallets, with Cheever sincerely marveling at “how a world that had seemed so dark could, in a few minutes, become so sweet.”

I

In fact, Cheever’s most famous story—one turned into a memorable 1968 film starring Burt Lancaster in the title role—revolves around a gracefully aging older man who intrudes on his neighbors by diving into their swimming pools: He’s a burglar in the open air, one who takes nothing but absorbs everything. In “The Swimmer” (1964), Neddy Merrill has persuaded himself that he has made a “contribution to modern geography” by perceiving that a succession of area swimming pools doubled as a kind of continuous stream that snaked through the county. He begins by bounding into the backyard of the Grahams. “He saw then, like any explorer, that the hospitable customs and traditions of the natives would have to be handled with diplomacy if he was ever going to reach his destination,” Cheever writes, pausing to observe the manners and mores of the various homeowners into whose pools Neddy dives as he paddles and pussyfoots his way back to what he thinks is still his own home. Finally, in a signature Cheever twist ending, Neddy is the victim of some unnamed, ill-remembered misfortune, and he clings to his native environment—these fine homes with their splendid pools—as though it was the mother country.

Countless American writers have sought to implicate members of high society—look no further than F. Scott Fitzgerald’s excoriation of the feckless snobbery of the Buchanans in The Great Gatsby—and a smaller but still significant number, among them Louis Auchincloss and A. R. Gurney, have treated this class with welcome empathy. Yet no major writer was as attuned to the pleasures, as well as the limitations, of his milieu as Cheever, who seemed at times to gently lampoon his suburbanites—as in his best-known novels, The Wapshot Chronicle and its sequel, The Wapshot Scandal (1964)—but, more often, was genuinely of two minds about all those well-maintained homes and leafy lawns.

In Bullet Park—arguably his most daring, inventive novel—Cheever honestly evokes the plain, uncomplicated affection its flawed but noble hero, suburbanite Eliot Nailles, has for his family. “The love Nailles felt for his wife and his only son seemed like some limitless discharge of a clear amber fluid that would surround them, cover them, preserve them and leave them insulated but visible like the contents of an aspic,” Cheever writes. He concedes that the sight of the couple seated at their kitchen table for breakfast “seemed to have less dimension than a comic strip,” but there is nothing one-dimensional about his evocations of the natural world—the flora, the fauna, even the claps of thunder—that so steadies Nailles. Even the act of Nailles taking a chain saw to insect-ridden elm trees is made to sound vigorous and lively: “The valley was protected and was, that morning, so unseasonably warm that the dead wood had released some fragrance—a smell of spice that reminded him of the cold churches in Rome.” John Cheever loved land. In a journal entry from 1977, he recounted seeing a Woody Allen movie with one of his three children. His primary takeaway? “The film lacks (I think) the heft and the smell of soil,” he writes. “And I glimpse the inflexibility and the parochialism of my tastes at this time of life. And so as soon as the sun is on the garden today I will return there.”

Bullet Park, which has the grisly, shocking contours of a crime story and is full of ambiguities about the world it offers up, is no mere paean to suburbia. In the end, however, Cheever seems to agree with Nailles’s son, who, after having been kidnapped by a murderous interloper to Bullet Park, insists to his father that he has no need to go to a hospital. “I have a headache and my eyes hurt,” he says, “but I’d rather go home.”

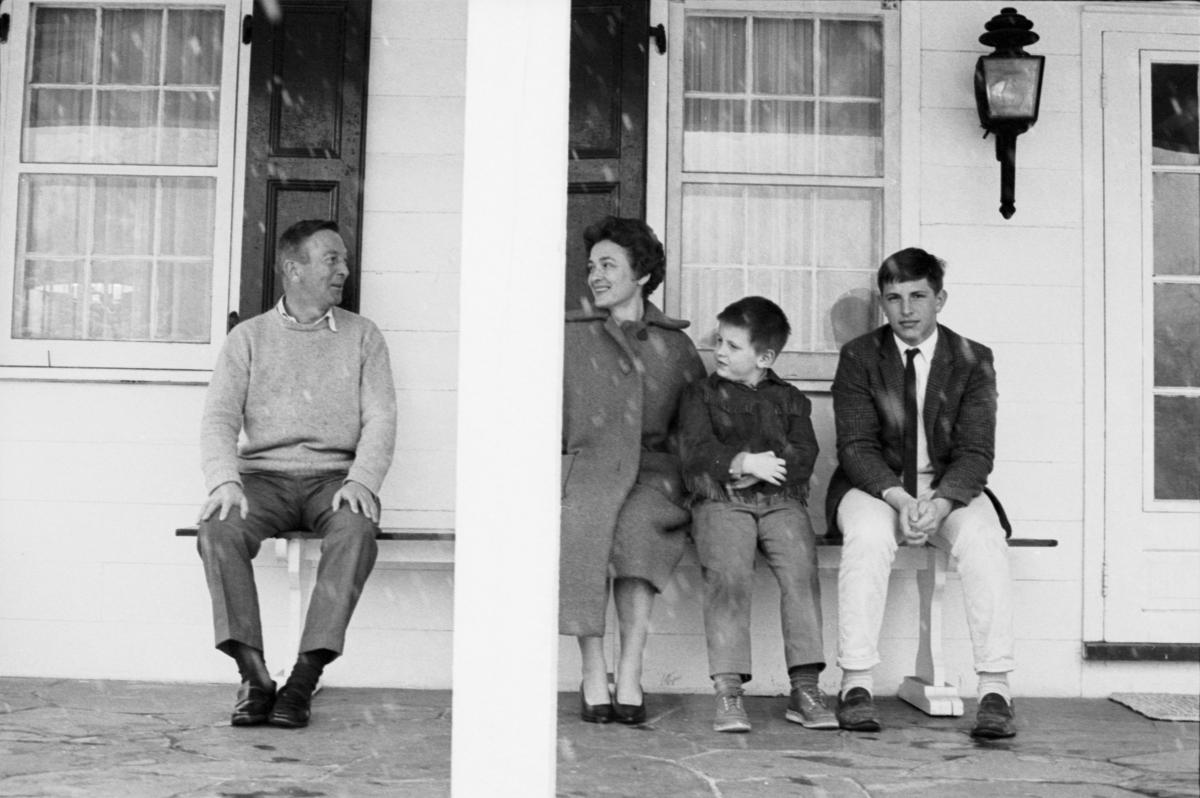

Home! “Home is the sailor, home from the sea, and the hunter home from the hill,” wrote Robert Louis Stevenson, and few writers ever have been as drawn to home, literally and metaphorically, as Cheever. In “Just Tell Me Who It Was” (1955), the pride the protagonist takes in his Dutch Colonial house—“in its many lighted windows, in the soundness of his roof and his heating plant—in the warmth of his children’s clothing, and in the fact that he had been able to make something plausible and coherent in spite of his mean beginnings”—is echoed in Cheever’s own nervous eagerness to acquire a piece of property to call his own. In 1960, well into middle age and father to three children with his wife, Mary, John Cheever at last plunked down money to buy an imposing house situated on six acres in Ossining, New York. In his biography, Donaldson writes of Cheever’s reluctance to fully enjoy his new dwelling and its attendant responsibilities (and financial commitments). “But,” Donaldson added, “as he lived there and put his labor and mortgage payments into it, he eventually forged a symbiotic bond with the place that involved a mutual respect.” As his daughter, Susan, remembered in her memoir Home Before Dark: “For years he roamed the house at night, convinced that it was about to burn down, or break down somehow, or just vanish into thin air.”

Cheever’s spread in Ossining did much to advance his public image as a courtly throwback of a writer—the man who took the bric-a-brac of nice neighborhoods and spun poetry from them. The “Chekhov of the suburbs,” they called him. In a number of his works, Cheever contributed to this perception, openly celebrating the comforts of hearth and home. In the conclusion to his brilliant television play The Shady Hill Kidnapping (1980)—in which a suburban tot temporarily goes missing—Cheever reads voice-over narration that sounds spoken from the heart: “Could anything be more exciting? This is a homecoming, nearly as old as the planet itself, nearly as old as the fall of darkness.” Permanency exercised Cheever. In Bullet Park, he attributes to Nailles what might as well be his own conviction that people bearing the names John and Mary could never, should never, divorce. “For better for worse, in madness and in saneness they seemed bound together for eternity by the simplicity of their names,” Cheever writes, and he and his Mary never separated, either.

Yet Cheever’s journals brought to the fore aspects of his work that might have remained submerged: The tone of beguiling contentedness that Cheever so often sounded in his fiction could have been arrived at only through internal convulsions. Yes, John and Mary remained married, but their outward unity masked stress fractures great and small. In one journal entry after another, Cheever describes himself as seeking the affections of his wife but, from his perspective, receiving only crumbs in return. On their anniversary in 1969, the two enjoy “the best hour we’ve had in months.” It doesn’t last, as Cheever explained: “But things are dim in the morning, and grow dimmer, I think, as the day passes, until by late afternoon Mary has stopped speaking altogether. I wash a Seconal down with whiskey and check out.” His alcoholism, which he conquered after receiving treatment in the mid ’70s, was the great near-calamity of his life.

Cheever was bisexual, maintaining multiple relationships outside of his marriage. His affairs with both women (including actress Hope Lange) and men seemed to serve as a relief valve for his frustrations with Mary; in his journals, he wrote jubilantly of being “the beloved of a young, beautiful, and passionate woman” (not his wife) but also of his “painful need for male tenderness.” Yet, like the husband in his great story “The Leaves, the Lion-Fish and the Bear” (1974) who pronounced his wife as looking “as lovely as ever—lovelier” following his own sexual encounter with a man, Cheever’s most radical act was to incorporate such extramarital liaisons into the context of his still-ongoing marriage, however flawed it was. In a 1968 journal entry, Cheever reflected that “the most useful” way to view marriage was as “neither larky nor desperate; a sense of how large a continent this is, and how complex the burdens.” He continued: “I think my mistake is to consider marriage vows as something on a valentine, and marriage itself as a simple romance.” A decade later, he sounded relatively at peace: “That I have homosexual instincts seems to me a commonplace.”

What are we to make of this man who was committed to his family but required affairs to nourish his soul? How are we to read this writer who was both drawn to, and repelled by, domesticity? Perhaps the secret to John Cheever was that he was honest with himself and didn’t finally shrink from his own contradictions—he loved his house and those who lived under its roof, but pursued relationships in which he felt he could be himself most fully. He could not wean himself from writing about executives and housewives and swimmers, but he felt compelled to write a novel set in the innards of a prison, Falconer. He was even aware of the irony of his lack of education but high standing among his peers, in ways that his superficial exchange with Updike and Cavett left unrevealed. “To have been expelled from Thayer Academy for smoking and then to have been given an honorary degree from Harvard seems to me a crowning example of the inestimable opportunities of the world in which I live and in which I pray generations will continue to live,” Cheever wrote in a 1978 journal entry.

For Cheever, life was not, as he put it, “a simple romance,” but a grand, messy love affair. In “The Swimmer,” Cheever writes of love as “the supreme elixir,” and he had it in abundance—overabundance, perhaps: for family, for lovers, for the simplest of things. He let his head and his heart roam freely, even if it took him no farther than his driveway. He once wrote in his journal of thrilling at the sight of a stray holly leaf while lugging a garbage pail. “That it means nothing at all is unimportant. It is important that I am stirred,” Cheever wrote, and so it is important that we are, too.