On a starlit morning of December 4, 1833, Mary Peabody rose early to inspect her trunk before setting sail from Boston Harbor bound for Cuba. Earlier that summer, she had been offered a position as a governess with a physician’s family outside of Havana, and now the twenty-seven-year-old was venturing out on an eighteen-month journey into the unknown.

Accompanying her was Sophia, her younger sister. Sophia was a talented writer and artist—she would later become one of only a handful of women in the United States to make a living as a painter. But her ability to work had been curtailed by frequent, debilitating headaches, and her oldest sister, Elizabeth, had arranged for her passage on the Newcastle in the hope that the trip would prove to be restorative. The plan for the trip was for Mary to teach while Sophia convalesced in the island’s healthful climate.

When she had learned of her family’s plan for the trip, Sophia had initially resisted. “[D]o not send me to the Havanas among strangers,” she wrote. “I do not want to lay my head under the pomegranates & citron trees—& do not know how I ever bore the idea of leaving my kith & kin.” It was Mary—always the more reasonable and diplomatic sister—who convinced Sophia of the idea’s soundness: “There is nothing in this plan, surely, that is wild or visionary—it seems to unite everything desirable, and I feel as if it might do you a real lasting good.”

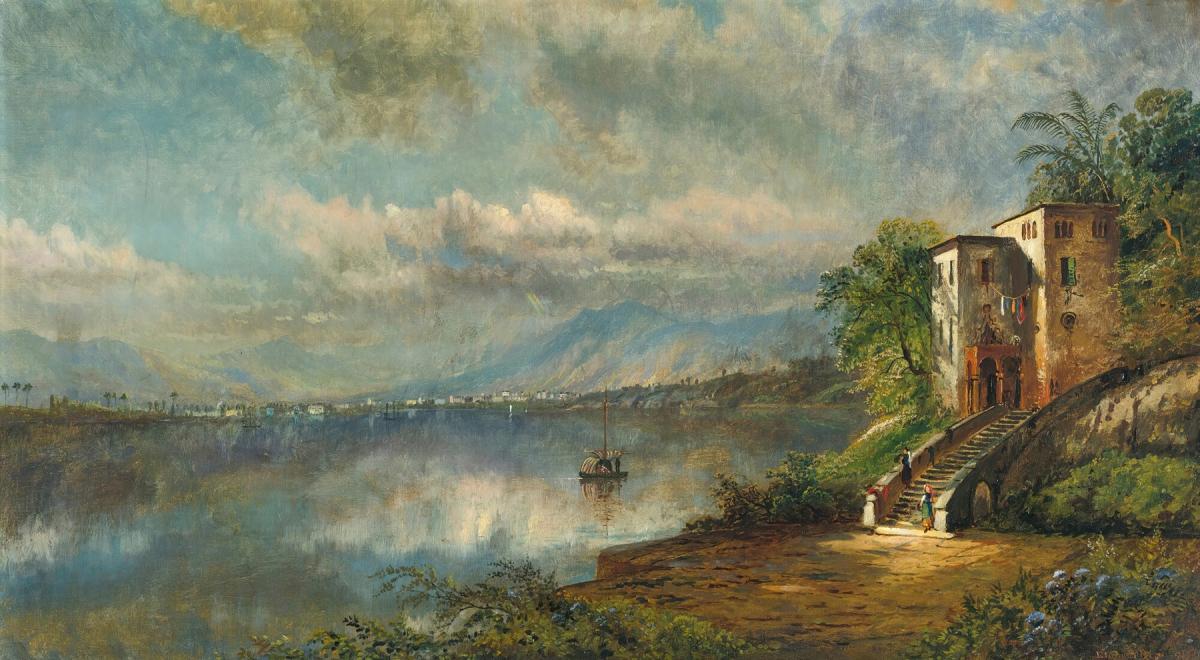

After leaving port, the Newcastle met crashing waves and icy gales. At times the sea was so rough that Mary and Sophia were lashed to hogsheads of beef to keep from being washed overboard. Then, just as quickly, the storm passed. The waters calmed. Within days, the weather grew deliciously warm and resolved into a vision of blues: endless sea and endless sky. Sophia befriended the captain, who lent her his spyglass to peer at the horizon, and a mile or so from Cuba she caught sight of a palm tree through the collapsible brass tube.

Almost immediately, Sophia’s health improved, as Mary noted in a letter to their mother soon after arriving. “[W]hen I tell you that Sophia rode 45 miles three days ago, over roads which pass all description for horrors, and that she slept soundly all that night, and was not wakened even by the great bell that hangs near the house, got up to breakfast, and has been better ever since, except being very tired and achy, you will allow that I was right in my expectations that she would be cured by this same trip to Cuba.”

Sophia soon wrote her own letter home, the first in a series of descriptive accounts that eventually came to be known as the “Cuba Journal.” In its entirety, the epistolary journal contained 56 letters and numbered more than 900 pages. Most of the correspondence was addressed to her mother, Eliza, but it soon gained a wider readership, thanks to Elizabeth who, tireless as ever, copied and distributed them to at least 25 friends. Among those who eventually read or heard portions of Sophia’s letters were Bronson and Abba Alcott, Waldo and Lydia Emerson, and the family of William Ellery Channing. Elizabeth even hosted reading parties, some of which lasted as long as seven hours, festive gatherings in which the guests took turns reading Sophia’s letters out loud.

There was good reason for all this interest. Throughout the nineteenth century, a steady wave of books about Cuba appeared in the United States by writers who included Richard H. Dana, the author of Two Years Before the Mast, and Julia Ward Howe, who attended Margaret Fuller’s Conversation salons along with Sophia and Elizabeth and eventually achieved fame by writing “The Battle Hymn of the Republic.” A year after Sophia and Mary left the island, a scurrilous anti-Catholic novel was published in the United States called Rosamond: or, A Narrative of the Captivity and Sufferings of an American Female Under the Popish Priests, in the Island of Cuba, with a Full Disclosure of Their Manners and Customs, Written by Herself. The novel, which told of a young widow seduced by a wicked priest, claimed to reveal “the general depravity of a whole country.”

These works suggest some of the reasons Cuba exerted a powerful pull on nineteenth-century imaginations. The island nation was exotic, lush: Spanish and therefore Catholic. It sat astride important shipping lanes, making it the object, according to former president John Quincy Adams, “of transcendental importance to the political and commercial interests of our Union.” Most important, it was a hub in the larger empire of slavery, a capital in the international economy built on labor stolen from enslaved Africans. The coffee enjoyed by New Englanders and the sugar with which they sweetened it were the result of the blood and toil of bosales: men and women captured on the coast of Africa and shipped by the Middle Passage to replace those who had died in the brutal conditions of Cuba’s plantations. The island was a flashpoint and symbol for pro- and antislavery activists alike.

Sophia’s Cuba Journal rarely addressed these topics. She considered art and politics incompatible and showed little interest in the island’s economy and history. She also sensed that even to consider the island’s brutal slave regime was to threaten her health. Her journal, concerned primarily with aesthetic descriptions, is almost entirely a record of intrinsic experiences—a chronicle of morning rides, subtropical flora, temperate climate, and the joyful emotions these things summoned within her. Part travelog, part memoir, part bildungsroman, the journal is the portrait of an artist awakening into a life of the senses—a world rich with color and fragrance and textures that were largely unknown in frosty New England. Like Mary Emerson’s Almanacks, it is also one of the earliest works of transcendentalist nature writing we have, anticipating Waldo Emerson’s Nature by two years and Henry David Thoreau’s Walden by more than a decade.

But it was the natural world that inspired Sophia’s most vivid descriptions. “And now we were riding by a dark impenetrable wood & over it was a new moon like a silver bow,” Sophia rhapsodized, “clouds of deep saffron upon the intense blue had caught & retained the glory of the sun’s farewell. In a few moments we were in another stately gothic gallery of bamboos . . . where two gorgeous peacocks were squalling like orphans, clothed in eternal mourning by the brilliant lime green hedge.” Her descriptions were prompted by the resumption of an old passion: riding. She had begun the sport in Massachusetts, but in Cuba she rode as often as possible, frequently rising before dawn to explore the six-by-six-mile plantation on a horse named Guajamon.

The lush surroundings delighted her artist’s eye. She savored the contrast between green vegetation and bright red earth, the middle ground fringed with “many flowers of brilliant hue, which I never saw before.” After a lifetime of chill New England winters, Sophia found Cuba’s balmy climate appealing, the atmosphere like a fine merino shawl, soft and warm, wrapped about her shoulders. One morning in early January, she wrote Eliza that she was sitting beside a rose tree in bloom, the temperature 78 degrees, and the landscape “a bright gorgeous dream.” She ate a sun-warmed guava (“had there been an Adam near, I am sure I would have said, ‘take thou & eat likewise’”); oranges, a rarity back home, were plentiful, cultivated in fine emerald groves near the hacienda. But it was the scenery that she responded to the most. Washington Allston, her former painting instructor, had recommended she “take views . . . of all the peculiar effects of atmosphere—clouds—trees &c—as a stock for future use.” Sophia dutifully sketched exotic plants, mountain ranges, cloudscapes, and the residents at La Recompensa.

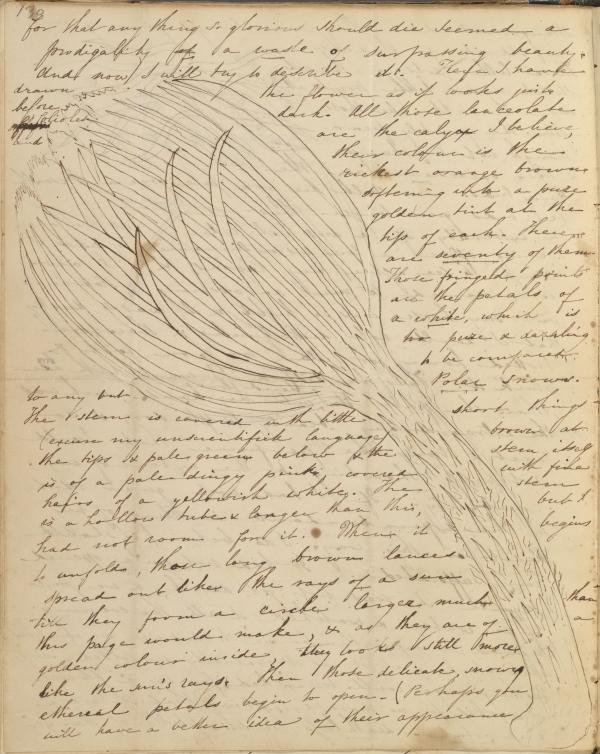

In one of the best-known passages in the Cuba Journal, Sophia described her discovery of the night-blooming cereus, a cactus whose flower blossomed like a candle in the night. She first noticed the glossy blooms during one of her sunset rides and hurried back to La Recompensa to enlist Mary to help collect them.

“When she put the gathered flowers into my hand, such was the extraordinary beauty & splendor, & so sweet & strong the perfume that I could not help shouting to the extent of my capability—If I had not given vent to the superabundant swelling of my heart in this way—I do believe I should have suffocated.” It was a moment of Keatsian rapture: the perfection of the flower’s beauty counterpoised by its tragic impermanence, and both blended in a powerful aesthetic experience. “Nothing more could be asked of a flower—I wished for no more excepting that it were immortal—deathless, unsusceptible of change for that any thing so glorious should die seemed a prodigality of waste of surpassing beauty.”

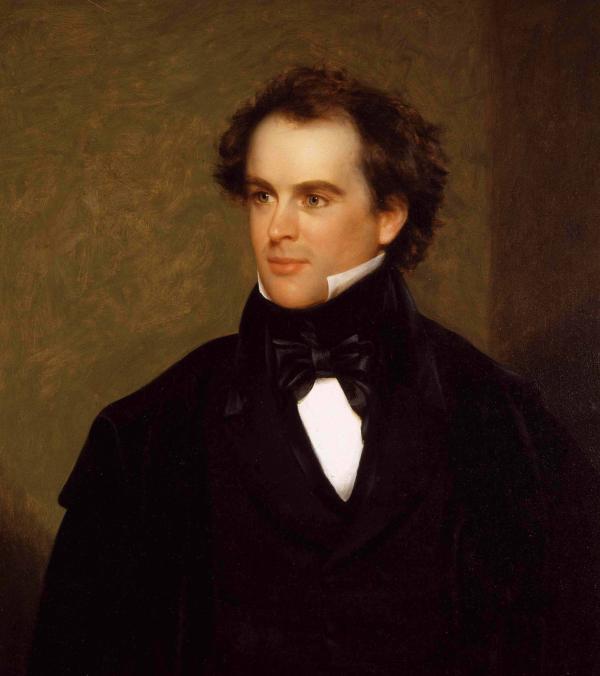

After eighteen months in Cuba, the Peabody sisters returned to New England. Cloistered once again in her parents’ house, without the thrilling thunderstorms and blazing heat of La Recompensa, Sophia’s illness soon returned. By late 1837, she was again bedridden with headaches. She quit painting downstairs, took meals in her upstairs bedroom. Sarah Clarke, an artist friend, reported at this time that Sophia was “more susceptible and requiring more careful nursing and seclusion than ever.” That was why she did not come downstairs one cold, blustery night in November when three visitors arrived and pulled at the doorbell. They were two sisters, Ebe and Louisa Hawthorne, each wearing a hood and cloak. Between them stood their tall, reclusive brother. His name was Nathaniel and neither Elizabeth nor Mary Peabody could take their eyes off him. Nathaniel Hawthorne was so beautiful that people stopped whatever they were doing when he passed. Ebe recalled that as a youth he was “the finest boy many strangers observed whom they had ever seen,” and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, who attended college with him 20 years earlier, thought him “a strange owl . . . but very pleasant to behold.” In an era that exalted outcast Romantic heroes, he exuded a silent charisma. This was largely the product of shyness; until the age of thirty he lived in his mother’s house, occupying an attic room and seldom leaving the premises (or so he said) before dusk. He avoided people on the street, avoided making eye contact. During what would soon become his long, secret engagement to Sophia, he kept her love letters tucked inside his breast pocket, like one of the characters he eventually became famous for: a recluse harboring a private mystery.

Elizabeth and Mary swooned over Nathaniel’s long hair, the deep staring intensity of his eyes. “He has a temple of a head (not a tower),” Mary soon wrote, “and an eye full of sparkle, glisten, & intelligence.” Elizabeth recalled, years later, the way he stood in the Peabody parlor “in all the splendor of his young beauty.” After presenting the Hawthorne siblings with a copy of the Iliad, Elizabeth hurried upstairs to Sophia’s sickroom, exclaiming, “O Sophia, you must get up and dress and come down! Mr. Hawthorne and his sisters are come, and you never saw anything so splendid—he is handsomer than Lord Byron.”

Sophia did not budge. “I think it would be rather ridiculous to get up,” she said. “If he has come once he will come again.” According to family legend—a legend nurtured by Elizabeth, who told it after its main participants were no longer alive to contradict her—sometime during the spring of 1838, Nathaniel paid one of his visits to Charter Street, and Sophia at last came down from her room. She instantly found herself drawn to him—as if he were a mesmerist whose attraction could not be resisted. Elizabeth said that when Sophia entered the room, Nathaniel “rose and looked at her intently.” The conversation proceeded stiffly; “she would frequently interpose a remark, in her low, sweet voice. Every time she did so, he would look at her again, with the same piercing, indrawing gaze.” From the very beginning, “his presence . . . exercised so strong a magnetic attraction upon her that instinctively, and in self-defense as it were, she drew back and repelled him.”

The truth about their courtship was more complicated. For one thing, Nathaniel was entangled in a romantic attachment with another Salem beauty, Mary Silsbee. For another, Elizabeth was herself deeply infatuated with him. Whether he reciprocated Elizabeth’s feelings has been the matter of much speculation. Certainly, he appreciated her enthusiasm for his writing and was grateful to Elizabeth for introducing him to her circle of friends, which included publishing contacts in Boston. But he kept his feelings to himself. Before long, local gossip linked the two. One Salem lawyer reported that “N. Hawthorne and Miss E. P. Peabody or some of the Sisters are betrothed—so the world may be blessed with transcendental literary production.”

It was during one of Nathaniel’s earliest visits that Elizabeth lent him the Cuba Journal. Possibly she hoped to expose Sophia’s invalidism and therefore her unsuitability for marriage. If so, the plan backfired. Five months earlier Nathaniel had written Longfellow to complain about his “great difficulty” as an author, “in the lack of materials; for I have seen so little of the world, that I have nothing but thin air to concoct my stories of, and it is not easy to give a life-like semblance to such shadowy stuff.” Now he kept Sophia’s journals, riveted by their frank depiction of a young woman’s thoughts. At least 11 passages made their way into his journal.

Sophia was equally fascinated with him. When Elizabeth went to West Newton to help her brother Nat open a school, Sophia hid behind her door upstairs whenever the handsome author visited. “I opened my door and tried to hear what he said,” she recalled. Unable to resist temptation, she at last stepped down the stairs to catch a glimpse of his handsome face, with its celestial expression. . . . What a beautiful smile he has.” Before long, she was hurrying to answer the door whenever the doorbell rang. She led him to the parlor and answered his questions about Cuba. When Nathaniel, who called her the “Queen of Journalisers,” told her that he wanted to use her experiences in a story, she wrote Elizabeth, “To be the means of any way of calling forth one of his divine creations is no small happiness, is it?”

The tentative courtship continued. When Nathaniel took a secret trip to western Massachusetts and upstate New York, he took the Cuba Journals with him. His own notebooks show the gradual absorption of their tone and material into a corner of his imagination. In one entry, for instance, he describes a richly hued sunset that illuminates a cluster of young women who are “warm and voluptuous—not languidly voluptuous, but with a mild fire.” The early mention of “warm and voluptuous” women associated with the surrounding wilderness, drawn from Sophia’s depiction of Cuba, suggests the heroines whom he would later create, including Hester Prynne in The Scarlet Letter and Zenobia in The Blithedale Romance.

If Sophia served as a muse for Nathaniel’s story, she was eager to reverse roles. Soon she took one of his stories for artistic inspiration. Late in the fall of 1838, she began an illustration for a story from his Twice-Told Tales, “The Gentle Boy,” a fable of Puritan cruelty and intolerance that Elizabeth particularly liked. Sophia’s line drawing is in the style of John Flaxman: spare and eloquent as a string of geese against a gray November sky. It represents the Puritan child, Ilbrahim, orphaned because his father has been put to death for being a Quaker. The illustration became widely known throughout Salem, and a local arts patron, Susan Burley, decided to fund a special edition of The Gentle Boy: A Thrice-Told Tale. Nathaniel crafted a preface for the new volume, speaking with joy that the story had “wrought an influence upon another mind, and has thus given to imaginative life a creation of deep and pure beauty.”

Reviews for the book were uniformly positive—particularly its illustration. Park Benjamin, writing in the New Yorker, praised Sophia’s “most exquisite genius.” Her old mentor, Washington Allston, admired her “simple severe lines” and allowed himself to hope that the artist would illustrate more of “Mr. Hawthorne’s exquisite fancies.”

But by the time The Gentle Boy appeared in January, Sophia and Nathaniel were involved in another collaboration. They were engaged to be married. The decision had been reached when both were in Boston. Nathaniel had accepted the job of Weigher and Gauger of the city’s Custom House, a position that Elizabeth had helped him find. Sophia was staying with friends to study sculpture with Shobal Clevenger, a former stonemason who had been commissioned by the Boston Athenaeum to create a bust of Allston.

For two magical months that winter, Sophia and Nathaniel saw each other as often as possible. (He “wants to come every day,” she informed Elizabeth, who remained in Salem, but “etiquette alone prevents him.”) Separated from their respective families, free to do as they liked, they experienced the special aloneness of young lovers, strolling through the Common at dusk, the city streets remote and muffled as snow drifted down. But there were obstacles to overcome. First and foremost was Elizabeth’s lingering infatuation with Nathaniel. In November 1838, Sophia had written her to say Nathaniel was but “a thousand brothers in one,” dissimulating her true feelings for the man Elizabeth considered her discovery.

Not until June the next year—six months after their secret engagement—did she reveal to Elizabeth her true feelings for Nathaniel. Elizabeth’s response was characteristically magnanimous. She assured Sophia she never wanted to marry. This was of course the same thing that Sophia had told Elizabeth. Now Sophia confessed that “I have often doubted whether you considered your destiny the proper one”—she was referring to Elizabeth’s unmarried state—and now felt “thankful to have you say that you think it is.”

Another obstacle was Nathaniel’s family. He insisted that the engagement remain a secret to his mother and two sisters. Ebe Hawthorne later speculated that her brother had kept silent because he had worried that news of the engagement might prove fatal to their mother. Equally plausible is Nathaniel’s almost pathological reticence which, according to Mary Peabody, caused him to suffer “inexpressibly in the presence of his fellow-mortals.” Regardless, he refused to make the engagement public. “The world might, as yet, misjudge us,” Nathaniel wrote Sophia shortly after she announced the engagement to Elizabeth, “and therefore we will not speak to the world.”

Excerpted with permission from Bright Circle: Five Remarkable Women in the Age of Transcendentalism by Randall Fuller. Copyright 2025 by Oxford University Press.