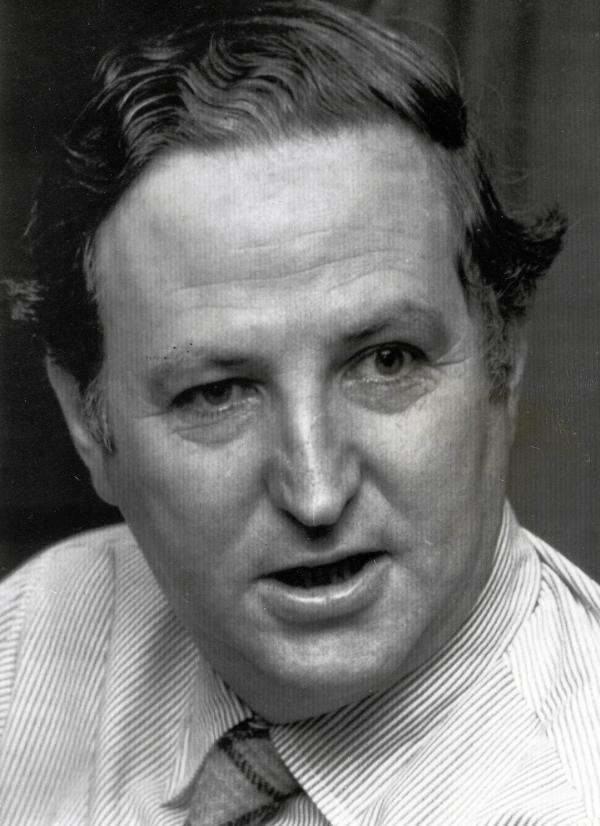

Late in the evening of Thursday, May 4, 1961, thirty-three-year-old William McBride got a call at his home in Blakehurst, Australia, to attend a complicated birth. McBride, an ambitious workaholic, ran one of the largest obstetrical practices in Sydney, Australia. He was on call 24 hours a day, seven days a week. A tall man with intense blue eyes and a beak of a nose, his brown wavy hair was always side-parted. He was wildly successful for his young age, and his confidence stirred envy in colleagues. But no one outside the Sydney medical community had ever heard of him. That was about to change.

Saying goodbye to his wife, Patricia, McBride got into his car and drove from his small suburban home into the city. In the darkness, he switched on the radio and heard the crackle of news: On the other side of the globe, John F. Kennedy had just completed his first 100 days as president of the United States. It was late autumn in Australia and one of the coldest days in 30 years. When McBride arrived at Crown Street Women’s Hospital—a four-story late-Victorian building, the largest maternity hospital in Sydney—he headed straight to the beige surgical room where the sterile instruments had been laid out. Dr. Paton, the thirtysomething-year-old anesthetist, grumbled about the chill.

On the operating table lay twenty-three-year-old Alice Wilson. The wife of a pharmacist, Alice was McBride’s private patient. He had overseen her whole healthy pregnancy. She had entered the hospital uneventfully that day when her labor had started, but by nightfall an erratic fetal heartbeat—the pace would quicken, then slow—alarmed the duty nurse. A cesarean was ordered, and McBride was called.

McBride lost no time scrubbing in and commencing the operation, and the procedure went smoothly. But when the baby was finally lifted from its mother, McBride and his team stood in shock: The baby was missing both arms, and on each hand—hands that seemed to sprout directly from the shoulders—was an extra finger.

They scrambled to do the routine treatments: clearing the newborn’s air passages, administering oxygen and vitamin K injections. When Dr. Paton slapped the newborn’s feet, the sound of healthy cries filled the room, and relief settled in.

“It seems quite normal otherwise,” remarked Paton, bewildered.

Since the mother was still fully sedated and he could postpone delivering the awful news, McBride returned home, tired and confused.

Snow fell thickly through the night, and McBride’s drive to the hospital the next morning proved arduous: Roads were closed, trees were toppled. But he was determined to check on Mrs. Wilson’s baby. When he finally arrived at the hospital, the attending nurse reported that the baby had been vomiting. X-rays revealed a bowel blockage. Alarmed, McBride transferred the baby to the Royal Alexandra Hospital for Children for emergency surgery. During the operation, the surgeon noticed another dangerously underdeveloped bowel area blocking digestion. Within the week, the baby was dead.

McBride was rattled. In seven years of delivering babies, he had never seen internal or external damage as severe as what he’d seen in Baby Wilson. Then, three weeks later, on May 24, McBride was called to attend the labor of another private patient, Susan Wood. Once again, an erratic fetal heartbeat necessitated a cesarean. Upstairs, in the same operating theater, with the same attending nurses, McBride lifted up Susan Wood’s newborn and saw that Baby Wood looked almost exactly like Baby Wilson. This baby, too, began vomiting. Within five days, that child had died as well.

Among the ward nurses, suspicion stirred. Since the start of the year, a surge of pregnant women had entered the hospital and miscarried, many of the fetuses displaying odd malformations. Even more troubling: All these women were Dr. McBride’s patients. The nurses relayed this to the night supervisor of the labor ward, Sister Patricia Sparrow, who alerted McBride to the “outbreak.” But it wasn’t until June 8, when McBride delivered another misshapen baby, to Shirley Tait, that the connection hit him with full force. When Baby Tait died after birth, the labor ward erupted in tumult. Three babies with wildly rare abnormalities born within weeks?

Meanwhile, John Newlinds, the Crown Street medical superintendent, had realized that the hospital’s congenital malformation rate was running triple the national average. He and his wife, a pediatrics registrar, had already set up a large wall map, using colored pins to mark the addresses of the ill-fated mothers, trying to untangle the mystery. But the couple had kept their map secret because a cluster of pins around the Atomic Energy Commission’s nuclear reactor south of the city might stir public panic.

On June 8, Baby Tait’s birth suggested to Newlinds a more obvious link—William McBride.

“For God’s sake, Bill,” Newlinds demanded, chasing McBride down in the corridor that day, “what is going on?”

On September 16, 1960, a senior sales representative for the Distillers Company, Walter Hodgetts, had visited William McBride in his private practice. A tall, gruff man, Hodgetts could turn on the charm in a sales pitch. He had a stellar sales record, and on that September day, he was peddling a top-selling sleeping pill that had been on the British market for two years—Distaval.

Having recently heard of the drug from a colleague at Bankstown Hospital, McBride gave Hodgetts a quick “yes”—he would try out Distaval as a labor sedative.

When a pregnant woman arrived at Crown Street with hyperemesis gravidarum—severe vomiting that risked miscarriage—and sedation and IV fluids failed to help, McBride recalled Distaval. The obstetrician considered himself cautious when it came to dispensing medicine; his grandfather’s first wife reportedly died on a hot summer day when she went to a Sydney pharmacist to buy citric acid for an elderflower cordial and was mistakenly given cyanic acid—akin to pure cyanide. McBride knew Distaval was marketed primarily as a sedative, but like many doctors of his day, he thought extreme morning sickness stemmed from anxiety, the angst over unexpected or unwanted pregnancies. Recalling Hodgetts’s assurance of the drug’s unparalleled safety, he ordered two Distaval pills from the hospital pharmacy and gave them to the sick woman. To his delight, her vomiting ceased. After that, McBride made Distaval his go-to remedy for nausea during pregnancy.

By May 9 of the following year, he was still so impressed with the drug that he wrote to the Distillers firm: McBride found Distaval “extremely efficient” in managing “morning sickness and hyperemesis gravidarum” and also an effective labor sedative. “I would be only too pleased to support any application to have this drug put on the National Health Service,” he assured the firm.

On May 24, 1961, Distillers confirmed:

We are in receipt of your evaluation of “Distaval” and would like to take this opportunity to express our appreciation for your interest and co-operation.

—F. Strobl, Sales Manager

This letter lay on McBride’s desk weeks later, after he had delivered the third malformed baby. As he sat in his office, sifting through patient medical cards, he wondered if the women might have suffered similar illnesses during pregnancy, or if they all lived near the Lucas Heights nuclear reactor. But he soon noted “nausea” as a common complaint and saw that, in each case, he’d administered Distaval.

Back at home, McBride locked himself away from his wife and children, probing the written material on Distaval. In his study, he thumbed page by page through the product’s red-covered “Advisory Service Bulletin.” According to the safety information, thalidomide had zero risk of acute toxicity—mice given massive doses had survived, and even human overdoses appeared safe. After swallowing 21 100-milligram tablets, a seventy-year-old British man had slept for 12 hours and felt only brief, lingering drowsiness. A two-year-old had fared fine after swallowing 700 milligrams. And long-term toxicity—tested in rats, guinea pigs, rabbits, and mice over 30 days—appeared nonexistent.

Nothing in the 20-page bulletin bumped McBride except for a single line: “Thalidomide is derived from glutamic acid.”

Another glutamic derivative, aminopterin, used to treat cancer, had been known for a decade to induce abortion in early pregnancy. McBride still had The Year Book of Obstetrics and Gynaecology with the first published report of that.

Scouring the Distillers brochure, McBride now realized nothing indicated that Distaval had actually been tested for safety during pregnancy. He then recalled a piece in the British Medical Journal earlier that year. Tearing through the piles of journals on his floor, he found the Leslie Florence letter about thalidomide and nerve damage. If thalidomide was harmful, what would happen if it crossed the placental barrier?

Penicillin and morphine were known to traverse the placenta—the former, protecting the fetus from infection; the latter, dangerously depressing fetal heart rate. If thalidomide bore any similarity to aminopterin as a glutamic acid derivative, then the drug might disrupt the embryo’s ability to metabolize glutamine, an essential amino acid for cell growth. This was why aminopterin stopped tumor growth and fetal growth. Would thalidomide likewise disrupt development of the fetus?

That was it! McBride wrote furiously into the night, titling his paper “Thalidomide and Congenital Abnormalities.” Simple animal experiments, he posited, would confirm if thalidomide crossed the placenta. Hours later, exhausted, he turned off his desk lamp.

The next morning, he set off to work in his car by 8:00 a.m., his handwritten manuscript beside him in his briefcase. His secretary could type it up for submission to The Lancet—a London-based journal with an international readership and a reputation for publishing quickly. Speed was of the essence.

At the hospital, McBride telephoned the Distillers office, where he reached Fred Strobl, the sales manager who had sent the grateful note weeks earlier. McBride shared his suspicion and told Strobl to report the news to the firm’s headquarters in England. But to McBride’s surprise, Strobl found his theory preposterous. The drug had been available in England and a host of other countries for years before it entered the Australian market—how would such a thing go unnoticed?

At lunch with John Newlinds, a frustrated McBride explained that he would have to launch his own animal experiments to prove the connection. But Newlinds didn’t want to wait for animal experiments. He telephoned the hospital’s chief pharmacist, Mrs. Sperling, and ordered Distaval removed from the pharmacy.

It was June 1961, and the Crown Street Women’s Hospital was one of the first in the world to suspend thalidomide.

From the book Wonder Drug: The Secret History of Thalidomide in America and Its Hidden Victims by Jennifer Vanderbes. Copyright © 2023 by Jennifer Vanderbes. Published by Random House, an imprint and division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.