530 CE: Benedict of Nursia

As a young man, Benedict of Nursia, born c. 480, was sent to Rome to be educated, but he was appalled by the worldly life of the capital. He withdrew and experimented with hermitism before becoming abbot of a monastery—it went badly. The monks tried to poison him. He narrowly escaped death and established his own monastery, Monte Cassino. Around 530, he devised the manual for monastic life known as the Rule of Benedict.

The Rule calls for monks to pray together seven times daily, for as much as four hours a day. Another three hours a day were given to reading, which the monks did aloud. The Benedictine regimen of prayer and work was severe by today’s standards, but it enabled individuals and communities to flourish.

766 CE: From Charlemagne to Napoleon

Made emperor of western Europe in 800 CE, Charlemagne was a great supporter of the pope and the primary patron of the Carolingian Renaissance. He underwrote projects to support monasteries and propagate the Rule of Benedict throughout Europe. Metten Abbey, founded in 766 in Bavaria, was one such monastery.

During the next millennium, the Holy Roman Empire shrank gradually until Napoleon established his own liberal, secular empire. “By 1814,” writes Fr. Colman J. Barry in Worship and Work, a history of Saint John’s Abbey in Minnesota, “scarcely thirty Benedictine monasteries remained as a disorganized . . . and tottering remnant of the armies of monks which had once Christianized and civilized Europe.”

In 1825, Ludwig I ascended to the throne of Bavaria. He “dreamed,” writes Fr. Colman, “of creating a union of political liberalism and traditional Catholicism.” Restoring the Benedictine monasteries lay at the center of his plans. After years of religious suppression, two aged priests, the last surviving members of the Metten monastery, returned to the cloister. They were joined by a twenty-three-year-old priest named Sebastian Wimmer, thereafter known as Father Boniface.

1845: From Metten to Minnesota

Ludwig I wanted to support German Catholics who were emigrating to distant parts of the United States, including places where Catholic churches were few or nonexistent. In 1845, Fr. Boniface made the case that Benedictines should be used as missionaries to the burgeoning German-American communities. It was a controversial suggestion, but ultimately a successful one, supported by Ludwig I.

Yet the idea remained controversial, even as Fr. Boniface, four students, and fourteen laborers arrived in the New World in the fall of 1846. Catholic leaders in New York and thereabouts counseled the Benedictines to turn back, saying that many other would-be missionaries had preceded them only to fail. An invitation to Pittsburgh, however, allowed Fr. Boniface to establish a foothold in the United States. The Benedictines took over a pioneer church called St. Vincent, a one-story schoolhouse, an old log cabin, and a dilapidated hut. Within a couple of years, fifty or so Catholic boys were receiving an education and training for the priesthood.

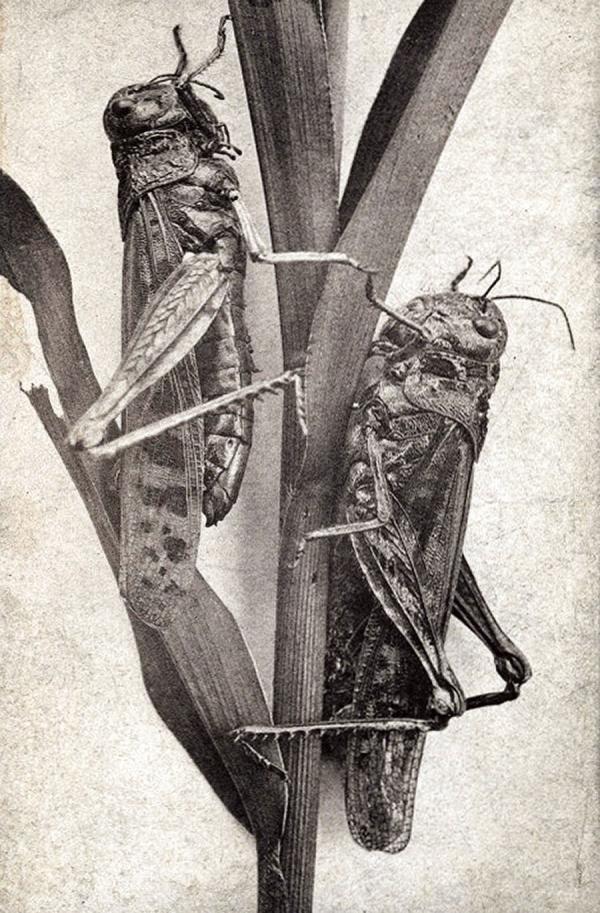

As the Minnesota territory experienced a massive immigration, five Benedictines arrived in 1856. After a perilous journey from St. Vincent, they began living in and working out of St. Cloud. Many were the practical and political challenges to establishing a Catholic ministry as well as an abbey and a school, but none so vivid as a plague of grasshoppers that descended on central Minnesota. Crops were annihilated, and the price of food soared. Priests had to sweep the altar of grasshoppers and altar boys had to beat their vestments clean before Mass could begin. Nonetheless, in 1857, Saint John’s College opened with two professors and five students.

1961: Monastic Manuscript Microfilm Project

By the 1950s, the Benedictine mission to Minnesota was a confirmed success. Saint John’s University in Collegeville began contemplating a building boom that would establish it as one of the most architecturally distinguished campuses and Catholic settings in the United States.

Back in Europe, the Vatican Library initiated a project to microfilm its manuscripts. At Saint John’s, it seemed to Fr. Colman that Benedictines should do the same for their own manuscripts. As president of Saint John’s, in 1964, Fr. Colman tapped Fr. Oliver Kapsner, then working in the library at St. Vincent Archabbey and College, to supervise.

The Louis W. and Maud Hill Family Foundation agreed to support the project. From talking to scholars, Kapsner learned that instead of preselecting certain manuscripts or parts of manuscripts to photograph, they should simply photograph everything up to the year 1600.

The only glitch was that none of the European monasteries where Kapsner proposed to photograph manuscripts had responded to his letters requesting cooperation. In October 1964, he traveled to Italy. Four monasteries refused him permission to photograph their manuscripts. He then headed to Switzerland and was refused permission at three more. A whole Swiss association of religious libraries, he learned, had rejected his proposal en masse at their annual convention.

“I had the feeling that by Christmas or shortly after,” he later wrote, “I would be on my return journey to the States, empty-handed.”

In Austria, however, his luck turned. At Kremsmünster Abbey, a message from the abbot awaited him: “Welcome. . . . You will begin your work here.” Other Austrian monasteries quickly followed suit.

In 1967 and 1968, the Monastic Manuscript Microfilm Library (later renamed the Hill Monastic Manuscript Library in honor of the Hill family’s longstanding support) received its first NEH grants. In 1969 it again received funding, specifically for cataloging its religious manuscripts, then totaling some nine million pages.

“By filming, centralizing and cataloging these manuscripts,” the application said, “St. John’s will make a large and basic contribution to humanistic knowledge.”

Several more grants to support cataloging and photographing were awarded in the 1970s, with each new application suggesting that what had begun quite modestly was a project growing to epic proportions.

Today the number of handwritten manuscripts photographed and digitized is well north of fifty million pages, representing multiple religious traditions and many countries beyond Europe, including several that have experienced political and military conflict.