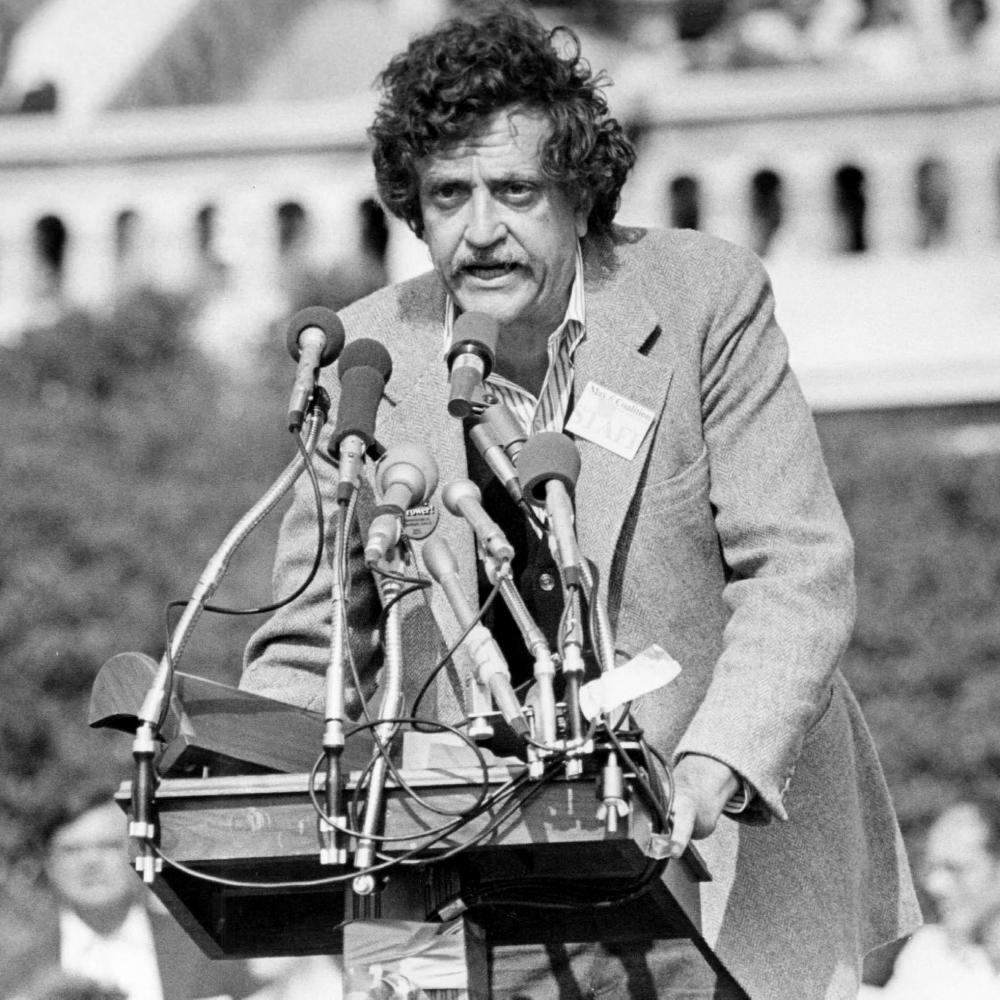

Kurt Vonnegut peered into the future and judged it to be lonely. Back when “face time” referred to in-person encounters rather than a virtual communication tool, Vonnegut railed against what he perceived to be the dehumanizing consequences of the Internet.

In a 1997 profile in the New York Times, Vonnegut compared technology enthusiasts of the era to those from an earlier, and nerdier, period in American life. “When I was a kid in Indiana, there were people with very poor complexions and not very popular who spent all their time in the attic or in the basement,” said the native son of Indianapolis, whose classic novels include God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater and Slaughterhouse-Five. “And these were ham radio operators. And they’d say—can you believe it—‘I’ve got a friend in Nome, Alaska.’”

Today, as the coronavirus pandemic has prompted stay-at-home orders from coast to coast, America has, temporarily at least, turned into a nation of ham-radio operators. We stream content rather than go to the movies, and we log onto Zoom calls rather than engage in office chitchat, and, if we must encounter another sentient being, we are told to venture no closer than six feet.

Vonnegut would surely be aghast at the virus, but he would be equally saddened at the interpersonal ramifications. In fact, over the course of his long literary career, Vonnegut emerged as a kind of Cassandra of loneliness—a poetic prophet warning of the toll on humans who were unable to connect with one another. The theme courses through his collected works. His marvelous short story “Who Am I This Time?” has at its center an actor who is electric when inhabiting a role but severely timid in everyday life. “He stayed away from all kinds of gatherings because he never could think of anything to say or do without a script,” Vonnegut writes.

Vonnegut’s novel Breakfast of Champions opens with this immortal line: “This is a tale of a meeting of two lonesome, skinny, fairly old white men on a planet which was dying fast”—reader, note that Dwayne Hoover and Kilgore Trout are described as lonesome first. And, in an address given to the graduates of the 1974 class of Hobart and William Smith Colleges, the author put his cards on the table in the simplest terms: “What should young people do with their lives today? Many things, obviously. But the most daring thing is to create stable communities in which the terrible disease of loneliness can be cured.”

Yet, no Vonnegut novel speaks more directly to our time and its attendant social isolation than Slapstick, or Lonesome No More!, which was published in 1976. Coming on the heels of the one-two punch of Slaughterhouse-Five and Breakfast of Champions, the novel was not met with adulation—not even by its own author, who was all too willing to concede that the reviewers had it pegged correctly.

“Slapstick may be a very bad book,” Vonnegut said in the Paris Review in 1977, adding, “Everybody else writes lousy books, so why shouldn’t I?”

It is an acquired taste. Slapstick functions as the autobiography of a senior citizen named Wilbur Swain, a one-time pediatrician who becomes a senator from Vermont before rising to the office of U.S. president, a much-diminished position in a future America crippled first by a cataclysmic increase in gravity and then an apparent contagion known as the Green Death. The title—a reference to Laurel and Hardy, the book’s unlikely dedicatees—may seem like a non sequitur, but the novel itself reads like a post-apocalyptic burlesque: Vonnegut jumps from one wild reference to another, writing of the harnessing of intelligence through telepathy, the presence of humans on the planet Mars, and the narrator’s best-selling tome on child-rearing, the flippantly titled So You Went and Had a Baby. Are you keeping up?

The well-orchestrated outlandishness of Slapstick may have put off some readers, but, as we all reckon with today’s coronavirus, some of Vonnegut’s flights of fancy have the shock of recognition. It isn’t simply that Wilbur recalls the events of his life against the backdrop of the Green Death, or that he sought the presidency after representing Vermont in the Senate, but that the character’s entire life is defined by the consolations of brotherly and sisterly relations, and the piercing pain of loneliness.

The offspring of high-born parents—in Vonnegut’s parlance, they are among the “fabulously well-to-do”—Wilbur and his twin sister, Eliza, are considered social outcasts due to physical deformities and what seem to most observers to be significant intellectual limitations. Secreted away in a palatial mansion, Wilbur and Eliza find that when they stay close to each other their intellectual capacity skyrockets—a neat metaphor for the stimulation we all get from spending time with learned friends.

“Thus did we give birth to a single genius, which died as quickly as we were parted, which was reborn the moment we got together again,” Wilbur says.

Vonnegut uses the fantastical tale of Wilbur and Eliza to pillory the doctrine of self-reliance, mocking the counsel of Dr. Cordelia Swain Cordiner, who has been dispatched to study the twins. “Paddle your own canoe,” she says. Hooey, Vonnegut says.

Much later, Wilbur—whose eventual separation from Eliza does not stop him from becoming a physician—enters the world of politics. Standing for president, he is a single-issue candidate. “I spoke of American loneliness,” he says. “It was the only subject I needed for victory, which was lucky. It was the only subject I had.” His slogan: “Lonesome No More!” (Vonnegut himself tested this slogan out on the graduating class of Hobart and William Smith Colleges in 1974, recalling that he had suggested it to the McGovern/Shriver campaign.)

Enacting an ambitious social-engineering scheme first conceived with Eliza, Wilbur resolves to expand extended families by bequeathing new middle names (made up of a noun followed by a number) to members of the American public. Bingo—your family just got bigger.

In Vonnegut's telling, Wilbur was filling a void in political life: A voter pitifully tells Wilbur of purchasing products and services because the salesman “seemed to promise to be his relative.” “Everybody with Uranium as a part of their middle name would be your cousin,” says Wilbur, whose actual middle name of “Rockefeller” is replaced, in this new order, with “Daffodil-11.”

Inevitably, Wilbur’s experiment runs into roadblocks. Individuals haggle over which extended families they are chosen to join, and a newspaper essay implores newly bulked-up families to look after themselves. “If you know of a relative who is engaged in criminal acts, . . . don’t call the police. Call ten more relatives.” Opposition comes when Wilbur’s “Lonesome No More!” is answered with an opposition campaign with the slogan “Lonesome, Thank God!”

Slapstick is so jam-packed with eccentric details—including the successful miniaturization of human beings by the government of China, whose U.S. ambassador is said to stand a mere 60 centimeters—that it is easy to overlook the sincere sentiments at its core, but they are surely present. In an autobiographical prologue that sets the stage for the farce to follow, Vonnegut expresses a measure of gratitude for having grown up among a vibrant extended family back home in Indianapolis. “Our parents and grandparents, after all, had grown up there with shoals of siblings and cousins and uncles and aunts,” Vonnegut writes.

By the same token, we should not get too distracted with the superficial details of the novel that seem to echo our own moment but instead focus on the deeper metaphor present in the central story of twins who are stronger with each other than without, and of a society that longs for the final virtue described in the French national motto of “liberté, égalité, fraternité.”

In a 1973 interview in Playboy, Vonnegut remembered hearing about a used-car salesman in Hawaii who happened to have his last name, prompting the author to seek out a meeting. Reflecting on the simple joy of finding yourself, maybe, kind of, related to a stranger, Vonnegut said, “So I looked him up and we had supper together. Turned out that he grew up in Samoa and his mother was a Finn. But the meeting, the connection, was exciting to both of us.”

Suppers, meetings, connections—they are the stuff of life. To judge by Slapstick and his other works, the record is clear: Kurt Vonnegut would miss those things as much as we do right now.