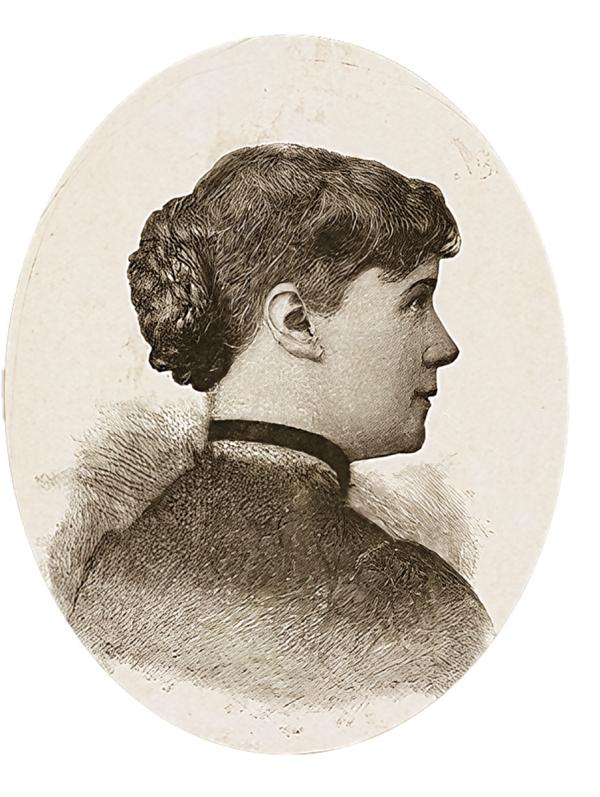

It was sometime during the spring of 1880, at a mutual friend’s house in Florence, when Constance Fenimore Woolson finally caught up with the acclaimed novelist she’d been hoping to meet for months. The forty-year-old Woolson had been waiting for a chance to speak with Henry James since she had disembarked in London the previous fall with her sister and her niece, determined to accomplish two goals, one personal and one professional. The first was to find a way to cast off the “armor of suffering” she had found herself trapped inside since her mother’s death the year before. The second was to fully commit herself to her literary career. Woolson was a woman on the cusp of middle age, an author with a modest but respectable reputation, handsome and charming, but rapidly approaching spinsterhood with no prospects for marriage. The trip had promised a much-needed change of scenery. But more importantly it seemed the perfect time for her to transform herself, and at long last to become, says her biographer, Anne Boyd Rioux, “a writer above all else.”

Arranging an introduction to a famous writer she’d never laid eyes on wasn’t that presumptuous. At least one mutual friend had encouraged Woolson to look up James once she was settled abroad. If the meeting did not provide her with connections she might leverage later, it would, at the very least, allow her to size up an author whose work she both admired and envied. But if Woolson was hoping that James might engage her in some writerly shoptalk or offer her a few words of advice, she was about to be disappointed. The man she met that day was coolly polite and distant, a “picture of blooming composure,” she later recalled, who surveyed her with grey eyes “from which he banishe[d] all expression.” He was unable to comment on any of Woolson’s essays, or the sketches she had published of her travels in the post-Confederate South, or her well-reviewed short story collection, Castle Nowhere. He was unfamiliar with her work, she soon discovered, and hadn’t read a word of it.

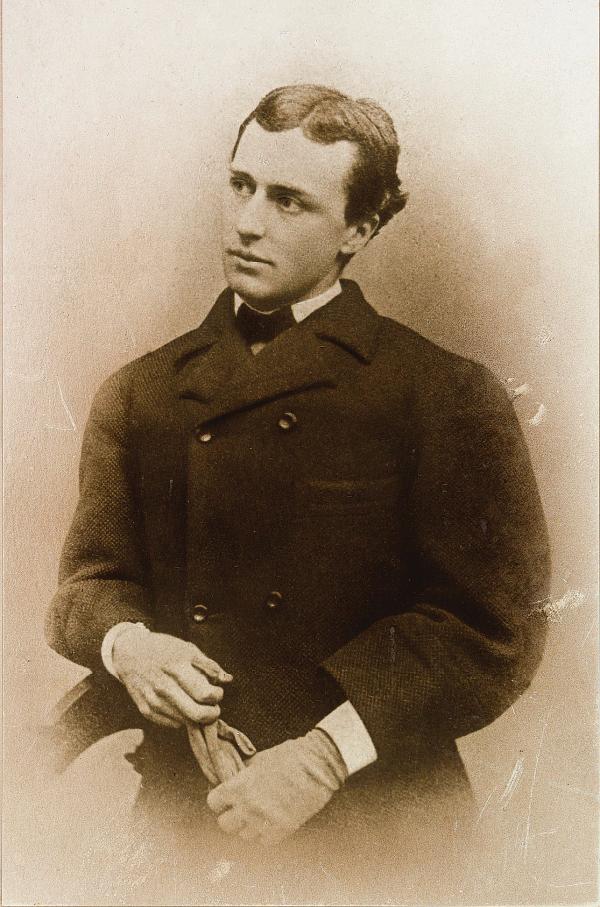

Henry James was thirty-seven years old when he first met Woolson. He was good-looking, a cultured and eligible bachelor, so perhaps he could be forgiven for assuming Woolson was going to be exactly like the other bookish women he tended to attract and didn’t care for—the “literary spinster, sailing-into-your-intimacy-American-hotel-piazza type,” as he’d once put it. But it didn’t take him long to figure out she wasn’t. “This morning I took an American authoress [on] a drive—Constance Fenimore Woolson, whose productions you may know, though I don’t,” James wrote to his aunt, not long after his first encounter with Woolson. Something had happened. He was still keeping Woolson at arm’s length—“amiable, but deaf” was how he mockingly described her to his sister—but she had piqued his curiosity. Before long, mornings that had been previously spent working on an early draft of his latest book, The Portrait of a Lady, were instead dedicated to touring Woolson around the city’s churches and galleries, introducing her to his favorite Giotto paintings and the statues of Michelangelo, or strolling through the Parco delle Cascine.

During their outings, Woolson discovered a new, disarming side of James. He was “perfectly charming,” she reported in one letter, and a “delightful companion.” As she eagerly took in the sights of the Old World for the first time, she may or may not have been aware that James was observing her closely, taking the mental notes that he would later use to flesh out Isabel Archer, the American ingenue protagonist of his novel-in-progress. He may or may or not have realized that she was observing him right back, filing away the mannerisms and expressions of her attentive new acquaintance, imagining all the ways in which she might use him one day as a character of her own.

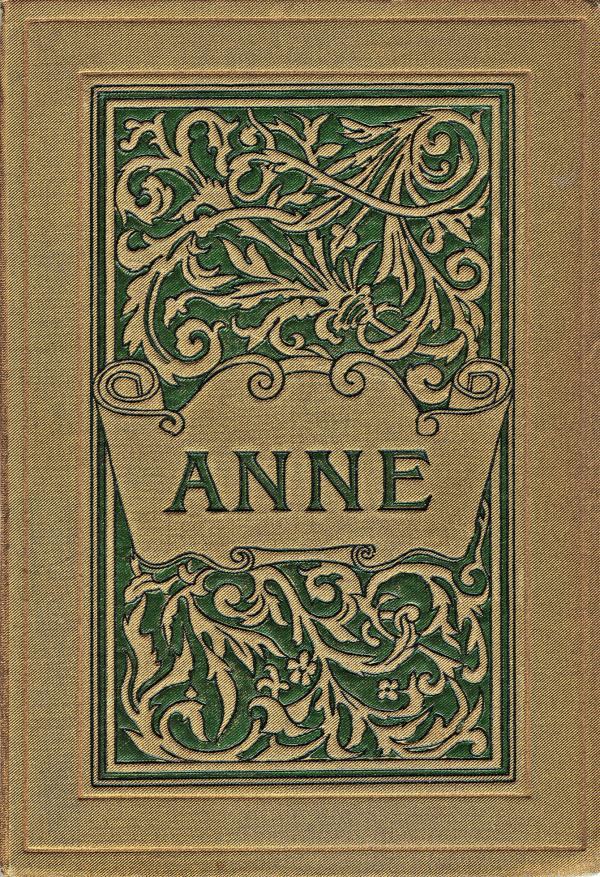

Either way, they appeared to have enjoyed each other's company. By the time Woolson departed for Venice in early June, she and James had surprised themselves by becoming friends. A few months later, Woolson published a short story in the Atlantic Monthly titled “A Florentine Experiment” about a man and a woman who meet in Florence and, with some reluctance and difficulty, fall in love. Shortly after that, her wildly popular debut novel, Anne, began its serial run in Harper’s Weekly. A year later, when the two writers met up again in Rome—to share, Rioux says, “some gossip and a pot of tea”—Woolson’s literary star had begun its ascent. But neither the positive reviews nor the fan mail from Anne’s readers had started to arrive yet and so neither Woolson nor James realized that her days as an insignificant “American authoress” were coming to an end.

At least for a while anyway. In Constance Fenimore Woolson: Portrait of a Lady Novelist, Rioux points out that Anne sold nearly ten times more copies than The Portrait of a Lady when the two books were first published and yet Portrait and James have survived in the culture in a way that Anne and Woolson have not. The fact that so much of Woolson’s fame rests on her role as James’s friend and confidant is unfair, says Rioux, who makes the case that Woolson’s fiction deserves far more recognition than it has received. Woolson tends to be situated in the canon next to minor American regionalists like Sarah Orne Jewett. These comparisons fail to acknowledge, however, her ambitiousness as an artist, Rioux argues. They turn her into the literary equivalent of a watercolorist dabbing dainty scenes of the places she had traveled to before she departed for Europe and never returned—the orange groves of St. Augustine, the foggy shores of Lake Michigan—when she was, in fact, forcefully painting her vision of the world on a much larger canvas. That vision included challenging and sometimes taboo subjects, including female rage, domestic violence, and alcoholism, but as a female writer, it was her fate to be typecast as frivolous and “pretty” despite her willingness to stake herself on a style, she once told a friend, that could be “ugly and bitter, provided it was also strong.”

In Woolson’s intensity and her obsessive dedication to her work—which could sometimes include ten-hour stints at her standing desk—she surpassed James, writes Lyndall Gordon, who explored the writers’ relationship in her book, A Private Life of Henry James. (Gordon, like Rioux, rejects earlier portrayals of Woolson as simply James’s fangirl with an “exalted notion of her own literary powers.”) In Woolson, she says, James had finally met a writer “absorbed in writing even more completely than himself.” No wonder he sought out her company.

Woolson’s ambitions were one subject she was not at liberty to discuss with James, no matter what else they might have shared with one another during their tête-à-têtes. In 1882, after learning from her publisher that Anne’s success had secured her a ten-thousand-dollar bonus and a request from Harper for the right of first refusal on all her future work, the elated Woolson wrote to her friend to share the news. James’s letter to Woolson has not survived, so we can only make assumptions about the ungracious nature of his reply from the quivering fury of her retort to it:

All the money that I have received, or shall receive, from my long novel, does not equal probably the half of the sum you received for your first, or shortest. It is quite right that it should be so. And, even if a story of mine should have a large “popular” sale (which I do not expect), that could not alter the fact that the utmost best of my work cannot touch the hem of your first or poorest. My work is coarse beside yours. Of entirely another grade. The two should not be mentioned on the same day. Do pray believe how acutely I know this. . . . Any little thing I may say . . . is said because I live so alone, as regards my writing, that sometimes when writing to you, or speaking to you—out it comes before I know it.

Whatever he had said had touched a nerve and seems to have wounded her deeply—in the way that only someone who knows you well can.

This letter is one of only four that remain from Woolson to James, and it raises the question that scholars have long wondered: What, exactly, went on between the two of them? Nobody knows, but everyone has theories. The fact that they were both so secretive about their interactions, along with the later revelation that James was most likely gay, has only fueled the speculation.

We do know that their nearly fourteen-year friendship consisted of two versions. There was the public-facing one they kept up—the one in which they referred to each other as “Miss Woolson” and “Mr. James,” the one in which they occasionally crossed paths during their travels and followed each other’s professional accomplishments at a polite remove— and then there was the private one. The one in which he affectionately referred to her as “Fenimore” (a reference to her famous great-uncle, James Fenimore Cooper) and she called him “Harry.” The one in which they would discreetly arrange to share a villa on the vacations they took together. It was the one in which James fretted about Woolson’s dark moods in his letters to their mutual friends, and the one in which he would sit next to her, talking patiently into her ear trumpet, so she could follow what he was saying. (Woolson suffered from an unspecified condition, beginning in adolescence, that gradually eroded her ability to hear.) The gap they constructed leaves a great deal of room for conjecture, but it’s this image of them conversing together—of her vulnerability, of his solicitousness—that is unexpectedly moving. They clearly meant something to one another, even if they lacked the willingness to explain to themselves or others what it was.

Without a doubt, what James and Woolson shared “was a kind of love,” Rioux asserts, “but one not sanctioned by their era.” An unmarried man and an unmarried woman could not expect to run off on vacation together and discuss their work alone over dinner and wine without attracting scandal. They were cagey about it; they covered their tracks. But the truth leaked out. James’s sister, Alice, knew enough to be suspicious of his “she-novelist” friend. “Henry is somewhere on the continent flirting with Constance,” she complained in a November 1888 letter to their older brother, William. A New York Herald article published in 1897, three years after Woolson’s death, which called James Woolson’s “principal mourner,” took some of its own jabs:

The truth about Mr. James’ bachelorhood is known to very few people; that truth is his heart was buried nearly three years ago in the grave that covered all that was mortal of Constance Fenimore Woolson. For a long time he had been this other author’s devoted slave, and, in spite of her deafness and increasing years, she possessed an attraction for him as intense as even the difference between their literary styles and methods. . . . It was one of the curious freaks of that mischievous imp, Cupid, that a feminine leader of romantic fiction should be so decidedly admired by an apostle of bald realism. Nothing more than an outward strong friendship was apparent betwixt the two, for Miss Woolson was not to be won.

This was precisely the kind of public exposure that James had dreaded, writes Gordon. One assumes the article would have stung Woolson too, although maybe not for entirely the same reasons. The Herald had not only turned her close friendship with James into the punchline of a joke. It had made a breezy but cutting distinction between James’s work and her own. And in doing so, it was confirming exactly what she had known all along.

Back in the winter of 1880, when Woolson’s letter of introduction to James was still tucked away in her trunk, and the two writers’ first meeting was still several months in the future, Woolson wrote a piece called “Miss Grief.” The story is told from the perspective of a successful and self-absorbed male author, who reluctantly agrees to assist a “shabby, unattractive,” and impoverished middle-aged female writer named Aaronna Moncrief in what he assumes will be a fruitless attempt to publish her fiction. Once he reads her stories, however, he is startled to discover that they possess a “divine spark of genius.” He sets about attempting to edit her work but is unable to do so—his attempts to fix the flaws he perceives in the stories only strip them of their strange but compelling power. Despite his efforts on her behalf, the narrator is unable to convince any of his contacts in the publishing world to accept her work, and, in the end, she dies, penniless and unknown. The narrator keeps one of Moncrief’s pieces in a drawer and pulls it out from time to time to ponder it. “Not as a memento mori exactly,” he concludes, “but rather as a memento of my own good fortune, for which I should continually give thanks.”

“No other story by a nineteenth-century American woman so powerfully dramatizes the yearning for literary recognition and the insurmountable obstacles women faced in pursuit of it,” observes Rioux, who says that “Miss Grief” “remains a powerful indictment of the male literary elite.” In the years since Woolson’s death, “Miss Grief” has become her most widely read work, not only because it so poignantly encapsulates the struggles women writers faced in having their work taken seriously, but because it contains so many eerily similar parallels to the real-life literary relationship that followed it. James was the powerful male writer who lived on to old age and eventually became known as “the Master.” Woolson committed suicide at the age of fifty-three and her most famous story is about a man whose shadow she couldn’t escape, a man who was actually not her “slave,” but a beloved confrere—this term was James’s—who failed to truly see her.

In the biographies of both Gordon and Rioux, James’s many shortcomings as a friend come across clearly. James was emotionally unavailable. He was insecure. He said sexist things about female authors. He was unwilling to laud Woolson’s accomplishments as a writer or to help further her career, even when he had the power to do so. Gordon goes so far as to accuse James of “professionally appropriating” the women in his life, and even Rioux—who takes a more generous view—observes that James, who could have kept Woolson’s legacy from fading after her death, “did little to promote” his friend’s memory.

In the long run, though, it seems doubtful that James could have done much to prevent Woolson’s slide into obscurity. If Woolson has waned in popularity, a great deal of the fault surely lies with the work itself, with the bleakness that runs through so much of it, and in its preoccupation with female self-abnegation, which has not aged well. “Miss Grief” is the story of a woman who sacrifices herself on the altar of her art, but that’s just one example. Martyrs are everywhere in Woolson’s novels and stories. There’s Katharine Winthrop in “At the Chateau of Corinne,” who gives up her literary aspirations at the behest of her fiancé. There’s Margaret of East Angels, who passes up the opportunity to be with the man she loves in order to stay loyal to her cheating, despicable husband. There’s Madam Carroll in For the Major, who struggles to conceal her true age from the senile man she married and now must care for. If Woolson’s work can be said to have “strong female protagonists”—to borrow a current popular publishing buzz phrase—those protagonists are steely only in their determination to subjugate their own happiness to people who are unable to fully understand or appreciate them. Reading Rioux’s biography, it’s hard not to be struck by the contrast between Woolson’s life and her fiction. Renunciation is a curious theme for a writer who so clearly chose to live on her own terms, one who declined to accept the conventional constraints of marriage and motherhood so she could have the freedom to travel and to read and to write her heart out. It’s also a sad one. It makes us, her readers, wish that she could have imagined something else for herself.

Woolson waged a lifelong struggle with depression. She worked hard to hide it, and she hid it well, but James—whatever his other failings—was observant enough to read between the lines. He was in London in January 1894 when the news reached him that Woolson, who had been spending the winter in Venice, had taken a fatal fall from her balcony during an illness, and he suspected almost immediately that her death had not been an accident. He had once used the utmost care in discussing Woolson with others, but that discretion vanished in the days that followed, as he wrote letter after letter, trying to make sense of the terrible news. Woolson’s suicide had resulted from a “sudden explosion of latent brain disease,” he insisted to one acquaintance. She must have “undergone some violent cerebral derangement,” he wrote to another. The frantic quality of this language is striking from the normally restrained James. It conveyed his shock, but it also revealed his desperation to cast Woolson’s death as something that could not possibly have been foreseen or prevented, says Rioux. Only two months later would he concede to his brother William that Woolson’s suffering had been much more pervasive, and that she had, in fact, possessed a “predisposition which sprang in its turn from a constitutional, an essentially, tragic and latently insane difficulty in living.”

Ultimately, there was nothing James could do but live with Woolson’s memory. And, fairly or unfairly, he used that memory to make the art that would continue to secure his reputation as one of the most highly regarded novelists of his era. James used Woolson’s life and death as material for his 1902 novel, The Wings of the Dove. But her haunting influence can be most clearly seen in The Beast in the Jungle, which he published a year later. The masterful novella has been read and admired by generations of James’s fans who have never heard of Constance Fenimore Woolson and would not recognize her presence in the quietly astute character of May Bartram, who dies at the end of the story and leaves the story’s narrator, John Marcher, overwhelmed by grief and regret.

It may be just as well that they don’t. “How did you ever dare write a portrait of a lady?” Woolson once tauntingly asked James. Her life was extraordinary, and it was full of the kinds of contradictions and tensions that the best writers do not attempt to shy away from or resolve. She was nobody’s tragic muse, Rioux insists, and in the end, all she wanted was to make the story her own.