In this excerpt from The Invisible Emperor (Penguin Press, October 2018), NEH Public Scholar Mark Braude recounts Napoleon’s relative ease during a stormy passage in the spring of 1814 aboard a British ship transporting him from France to Elba. The former emperor of the French, king of Italy, mediator of the Swiss Confederation, and protector of the Confederation of the Rhine spent nearly a year in exile before his escape and return to the world stage.

From his leaking cabin, the imperial paymaster, Guillaume Peyrusse, wrote to his father about being rocked so violently by the waves that he fell out of bed and smacked his head on the wet floor. The sounds of overnight hammering had him convinced the ship wouldn’t survive the crossing. When he voiced his concerns about the rough weather to some midshipmen on watch, they laughed and told him winds ten times stronger could hardly be called a storm by their reckoning. He spent the rest of the trip sulking in his cabin, trying to soothe his seasickness with ham, tea, and sweet Málaga wine.

Napoleon enjoyed a more comfortable night than did his paymaster. The ship’s captain, Thomas Ussher, had given the deposed emperor the run of his quarters, which spanned the Undaunted’s stern, while he shared a smaller night cabin with Generals Henri Bertrand and Antoine Drouot, the Frenchmen’s beds separated from his own by a flimsy screen.

Out on the bridge the next morning, cup of black coffee in hand, Napoleon reported that he’d never slept so soundly and that he felt in excellent health. The ailments from which he was silently suffering (gallstones, hemorrhoids, urinary infections, stomach cramps, and swollen legs—not an unusual list for that era) would have been exacerbated by the sea journey, and Napoleon wasn’t a great sailor. Yet the farther south he traveled the happier he seemed to be. His official allied overseer, the young Scottish officer Neil Campbell, overheard some French officers saying they had never seen their emperor looking so relaxed.

Away from France on a 38-gun ship, he no doubt felt safer than he had in months, even if his current protectors had until very recently been among his fiercest enemies. And so long as the Undaunted sailed toward Elba, he still occupied the unsteady space between departure and arrival, where the past felt not quite real and somehow reversible and the future could still be shaped to suit his needs.

The Undaunted passed within “a cannon’s shot” (Peyrusse’s words) of the northern tip of Corsica on May 1,

1814. Peaceful salutes were exchanged with a squadron patrolling the coast, which cheered the passengers, still unsure if anyone in the region knew whom their ship carried or how they might react to that information.

Accustomed to commandeering any ship in his sight, Napoleon demanded that the captain of a passing brig be brought aboard to give news from Corsica, but Ussher, laughing, denied the request. In a letter to London, Ussher would gloat about these kinds of intimacies with the emperor. As they had sighted the Alps from the bridge, he wrote, Napoleon “leaned on my arm for half an hour, looking earnestly at them” and then smiled at Ussher’s remark that he had “once passed them with better fortune.”

A few months earlier Ussher had cut out a newspaper rendering of Napoleon and pinned it to a wall above his table so he could advise guests aboard the Undaunted to study the image and commit it to memory. The word back then had been that Napoleon would try to escape across the Atlantic rather than surrender. The Royal Navy might require their help to spot this enemy in disguise, Ussher would tell his dining companions.

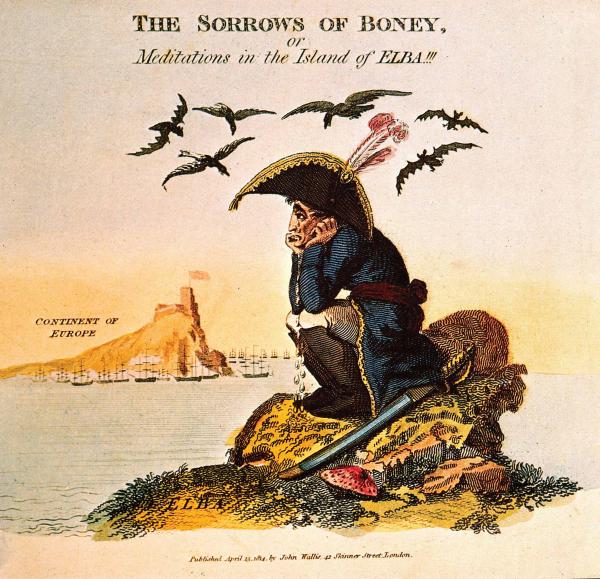

Now he shared the same table with the man from the picture, whose likeness he would have seen in so many different forms: in pen, oil, clay, silver, stone, wax. Given the relative freedom of the British press, he might have seen Napoleon as the snub-nosed imp who pestered John Bull in inky caricatures, or as Gulliver, helpless in the palm of a Brobdingnagian King George III. Perhaps he’d seen some version of Jacques-Louis David’s famed painting of the general as a modern Hannibal astride an enormous charger subduing the windswept Alps, or of Ingres’s severe, laurel-wreathed emperor, all ermine and purple velvet. His face would have come to Ussher head-on, at three-quarters, and in profile (the subject increasingly preferring this last angle as his features softened with the years), with the penetrating blue-gray eyes never meeting the viewer as an equal but always looking off to some luminous future he alone could see.

Only natural, then, that when describing the real man, the best Ussher could do was to compare him with a representation. “The portrait of him with the cockaded hat and folded arms is the strongest likeness I have seen,” he wrote, adding that Napoleon’s pudginess suited him finely, saying that “he looks uncommonly well and young and is much changed for the better, being now very stout.” Ussher added that “someone said I was like Bonaparte, but not so well looking. It was a Frenchman and he thought even with that amendment that he paid me a great compliment.”

As they hugged the west coast of Corsica a storm front moved in. Napoleon asked if they could be anchored at the harbor town of Ajaccio, his birthplace, which he hadn’t seen since an unpleasant five-day layover during his journey back from Egypt, 15 years earlier, waiting for winds to carry his ship home to France. Ussher felt that the poor weather made an anchorage too dangerous, but as a sop Campbell told Napoleon he could write letters to friends on the island. Campbell had the letters sent straight to Corsica’s commanding officer with orders they be opened and destroyed.

Before sunset, a passing tartane instigated contact with the Undaunted, and Campbell and Ussher allowed its Corsican shipmaster to come on deck, seeing it as a way to pass the time. The sailor spoke of how eagerly his fellow islanders had declared themselves for the restored Bourbons. Unaware that Napoleon numbered among his listeners, he praised the new state of affairs somewhat too enthusiastically for the emperor, whose loud sigh caused the shipmaster to observe him more carefully. He continued his report, now even bolder in his support for the Bourbons and throwing in a few choice oaths for emphasis. Napoleon walked away while he was midsentence and asked Ussher to tell the man to return to his ship.

The skies cleared the next morning and the Undaunted sailed on, eastbound. Napoleon spent much of the day reading. He had taken nearly two hundred works from the library at Fontainebleau, the sprawling castle complex to which he had fallen back as the allies occupied Paris a few weeks earlier. Among these books was Thiébaut de Berneaud’s travelog, A Voyage to the Isle of Elba, which advised that on approaching Elba one should expect to see nothing more than a few “roads rugged and uneven, cottages deserted. Ruins scattered over the face of the country, wretched hamlets, two mean villages, and one fortress.” Napoleon would have read that “the mountains of the Isle of Elba . . . together present only a mass of arid hills which fatigue the sense, and impart to the soul sensations of sorrow.”

Despite the descriptions of supposedly barren landscapes, Berneaud’s book was an odd sort of love letter to Elba. He was one in a long line of writers who believed they had discovered something enviable in an island people somehow spared from the miasma of civilization. The Elbans, he wrote, were “endowed with a certain sprightliness of imagination, which renders them capable of receiving the strongest impressions; thence proceeds their predilection for extravagant and romantic tales. . . . They are unacquainted with the monstrous luxury of cities.” Berneaud claimed they had none of “the cunning, the laziness, or the listlessness so natural to a southern people,” and though Elban women were “not in general beautiful,” there were “pretty girls in the western mountains and at Rio [a mining town on the east coast]. They press their swelling bosoms under enormous busks laced tight with ribbons.”

Though the Elbans appeared insular and primitive to outsiders, they looked out on the world from a perspective that was broader than that of most mainlanders. Seafaring people had their minds opened by always being on the move, fishing, sailing, and trading. They were among the globe’s most cosmopolitan souls, forced by geography and economic necessity to regularly do business with strangers. Being such rich economic prizes, capable of sparking wars among powers thousands of miles away, islands were forever being conquered, colonized, and traded, leading to polyglot populations. Elba had its share of outdated customs, parochial thinking, and isolated villages, but many of its men and women, especially in its capital, Portoferraio (the “Port of Iron”), on the island’s northern end, would have met daily with travelers from afar.

Unknown to anyone on the Undaunted was that reports of the allied victory had thrown Elba into open revolt. A British naval blockade had kept the island cut off from the continent since December and starvation loomed. Troops remained under the nominal charge of the French governor, Dalesme, but just barely. He had once controlled a force of five thousand men drawn from France, Corsica, and the Italian peninsula, but, by early 1814, so many soldiers had deserted that Dalesme was left with only five hundred Frenchmen garrisoned at Portoferraio.

Just west of Portoferraio, in Marciana, the townsfolk flew crude versions of the Union Jack and had tried unsuccessfully to get the captain of a passing British ship to land and take control. They burned Napoleon in effigy, singing and dancing around the flames. To the south in Porto Longone (present-day Porto Azzurro), a mutiny that started with villagers tearing tricolor flags had escalated to their shooting the French commanding officer and hacking his body to pieces. Farther along the coast some villagers openly declared allegiance to Napoleon’s brother-in-law Joachim Murat, while a few hard-liners around the island saw this as the time to throw off the rule of all masters forever and urged a total revolution.

Still, it was a celebratory time on the island. On the first day of May, following a centuries-old tradition, unmarried men wandered the villages to sing serenades in praise of springtime love and the charms of the local maidens, who rewarded them with little corollo cakes as syrupy as the lyrics being sung. No one wanted to abandon a tradition that had led to so many marriages, and so the sounds of protests and politics were made to compete with poetry and guitars.

Adding to the confusion, Dalesme had no idea whether Elba was still a French possession. A British ship had landed under the flag of truce late in April and its messenger presented Dalesme with an order to relinquish control to the British, and had shown him French newspapers detailing Napoleon’s abdication. But Dalesme dismissed this as a ploy to lure him into surrendering, and the ship sailed back to the mainland. It was replaced the next day by another British ship, carrying a representative from the French Provisional Government, who finally convinced him that Napoleon was en route to Elba.

Armed with this latest intelligence, Dalesme told his men to be on the lookout for the French corvette Inconstant, which, as the French official had told him, would be carrying Napoleon and flying Bourbon white. Any ship not fitting this description was to be treated as an enemy. No one on Elba knew that Napoleon had in fact refused to sail on the French corvette, which he deemed insufficiently armed, and instead insisted on being taken into exile aboard the British Undaunted.

On the night of May 2 the Undaunted was becalmed near the island of Capraia. The ship gave a salute, answered by the island’s battery, after which some officials were invited on board. They spoke of how things stood on nearby Elba. The passengers could just make out the fortifications topping the rocky ridge of Portoferraio, a shadow against the bloodshot sky. They took turns on the telescope. “Each of us,” recalled Peyrusse, “looked eagerly at this new country.”

They reached Elba the following afternoon. A crossing that in fine weather could be done in two days had taken them nearly a week. As rowers pulled the tall ship toward the small horseshoe-shaped harbor tucked south behind Portoferraio’s main town, away from the open sea, watchmen at the edge of the quay sighted the ship flying the Royal Standard. Dalesme ordered them to aim their heavy cannons at the Undaunted, but after some minutes of standoff Ussher gave the signal for parley and the case of mistaken identity was solved.

Napoleon’s aide-de-camp Drouot was brought to the quay, accompanied by Campbell. “The inhabitants,” wrote Campbell with his typical understatement, “appeared to view us with great curiosity.” On a bluff overlooking the harbor, the two men entered Fort Stella, named for its star-shaped footprint, where they met with Governor Dalesme. He was still struggling to make sense of this surreal change of events and later said he was only convinced that the handover wasn’t a ploy when he saw General Drouot, “whose integrity was a byword in the French army.” Drouot signed some documents to officially take possession of Elba in the name of the emperor Napoleon, who remained out of sight on the Undaunted. They strategized about how to smoothly transfer control of the island.

The landing party sailed back to the Undaunted. They brought along a Frenchman named André Pons de l’Hérault, who, as administrator of Elba’s mines, oversaw the bulk of the island’s economy. He went by Pons, though to the thousands of islanders depending on him for their livelihoods he was simply Babbo (Father). While obscure by the standards of the French Empire, he was the nearest thing Elba had to a Napoleonic figure.

Napoleon and Pons had crossed paths in different military and political settings over the years. When they first met, in Toulon in the fall of 1793, both were ambitious artillery commanders of the Revolutionary army engaged in taking back the harbors of that port town from the British. It was in Toulon that the 24-year-old Bonaparte received his first significant public notice for orchestrating a clever barrage that broke the British siege and resulted in his promotion to brigadier general. It was also in Toulon that he tried, on Pons’s urging, his first taste of bouillabaisse, the traditional Provençal fish stew.

Pons described himself in his memoirs as “republican before there was a Republic” and had remained faithful to France over the years, pleased to serve its government in whatever form it took. But by 1814 he was disillusioned by what he saw as Napoleon’s corruption of republican values in his search for personal glory. As with many sons and daughters of the Revolution, he couldn’t forgive the former General Bonaparte for crowning himself Napoleon I. The opulent coronation at Notre-Dame, where Napoleon had snatched the crown from the pope to place it on his own head; his marriage to an Austrian archduchess; his placing three brothers and one brother-in-law on foreign thrones; his reinstating slavery in the Caribbean colonies: All were abhorrent to Pons.

“Now I was to appear before the great hero who had voluntarily thrown away his glorious halo!” he wrote. “I was to appear before the extraordinary man I had so often found blame with, even while admiring him, and on whose behalf I had so often prayed that he might win his holy struggle on our sacred soil! I was to present myself to the emperor Napoleon, but aboard a British frigate! It all seemed like a dream, a painful dream, a frightful dream.”

On greeting Pons, Napoleon would have seen his own aging process reflected back to him. The mining administrator had grown quite plump and wore thin wire spectacles, which he attributed to too many nights poring over ledgers by lamplight. He practiced the bald man’s trick of growing out his meager tonsure of hair into long strands to be deployed at various angles. Though Napoleon’s junior by three years, he carried himself like someone who had already seen six or seven decades, if restful ones.

To Pons, Napoleon no longer even closely resembled the long-haired, rake-thin officer he’d known in early adulthood. His face had gone puffy and pasty. And yet aboard the Undaunted, “carefully dressed” in his pristine green coat, white breeches, and red boots, he looked to Pons like “a soldier ready for an official reception.” His bright eyes offered little sign of shame and retained a trace of the ineffable glimmer that for the past two decades had helped to make him the focus of any room he entered.

Campbell, in the background, tall and silent, put Pons on edge with his “artfully bandaged” head, his forced smile, and his searching gaze, “the perfection of the British type.” Their instant dislike was mutual. In his journal, Campbell referred to the unassuming Pons as “a violent intriguing fellow.”

Napoleon said little that night. Pons recalled that when he spoke of the events that had brought him there he talked as if he were detached from the action and had only read about it in the papers, and that he managed with a few fatherly nods and grave looks to convey that he understood everything these excited children wanted to tell him, even as they tripped over their words. He pledged to do right by the people of Elba, who were now his only concern. It was agreed that he should debark the next morning so that a suitable reception could be arranged overnight.

Dalesme and Pons rowed back to the quay, where all sorts of rumors spread among the gathered crowd. Children stayed up late, trying to make sense of the story of the Corsican brought from France on a British ship to become Emperor of Elba.

Across the water, Napoleon paced the bridge of the Undaunted. He would have seen a constellation of flickering lights. Most, though not all, of the three thousand inhabitants of Portoferraio had placed candles in their windows as a sign of welcome.

From The Invisible Emperor by Mark Braude, published on October 9, 2018, by Penguin Press, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2018 by Mark Braude.