In his poem “Sailing to Byzantium,” William Butler Yeats pictures an aging man. “That is no country for old men,” the oft-repeated verse begins. He is withering away, a “tattered coat upon a stick.” But he can escape, he insists, if only his soul can stir with song. So he sets sail for Byzantium, a “holy city.” There he asks the sages on a gilded wall to be his “singing-masters,” to pulse through him, so he might live forever.

That sense of art’s redemptive power runs through “Africa & Byzantium,” a survey of North and East African work from the fourth through the fifteenth century and into the present day, which opened in the fall at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and travels to the Cleveland Museum of Art in April. Lining the galleries’ slate-gray walls are romantic trysts and crimson and gold icons, lavish feasts and gemstones set in pearls. No less charming are the stories they tell of scribes who agonize over their work, of people who cast improbable spells—each splendidly alive to us.

Take the Lady of Carthage. Framed in a marble-and-lime-stone mosaic, she bewitches with impossibly large eyes. Edged in diamond-patterned spirals of brick reds and emeralds, the figure—a personification of the Tunisian port city or the wife of the Byzantine emperor Justinian—offers a blessing, her rosy-cheeked face encircled in diffuse gray blues. There’s a gravitas about her, something all-knowing: She exists out of time.

Until recently, Roman and Byzantine art in North and East Africa—like the Lady of Carthage mosaic—was not considered African, says curator Andrea Myers Achi. Objects like these were “in Africa but not of Africa,” she explains. The Met installation, by contrast, pays homage to the African context of the monks and writers, painters and weavers who made these wonders and lived alongside them. This is their story, elegantly told.

But it’s not a Byzantine story, exactly. The term “Byzantine” was coined in the mid sixteenth century by the German historian Hieronymus Wolf to describe the eastern Roman Empire, where the capital city, Byzantium, later renamed Constantinople, held sway. “‘Byzantine’ is made up in the same way ‘Medieval’ is made up,” Achi notes. The artists in the show wouldn’t have referred to themselves as Byzantine. But the adjective remains useful, especially in art history. The eastern half of the Roman Empire had a distinctive style—replete with radiant icons and mosaics—that spread to North and East Africa, where it took on forms and tonalities all its own.

A second-century panel painting of the Egyptian goddess Isis brings this to bear. The figure, rendered in tempera on wood, has rounded eyes and dark rivulets of hair, bold flourishes springing this way and that. She anticipates the Lady of Carthage, completed two centuries later. There is a solemnity about the pair, a calm amidst a storm of rippling brushwork. Here styles unfurl and intertwine, ever fluid.

In the next room is the show’s crowning jewel: an exuberant sixth-century icon from the Monastery of Saint Catherine in Sinai. The work is small, almost demure, but it throbs with life. In it, the Virgin and Child are flanked by Saint George and Saint Theodore. Behind them, two angels are suspended, beautifully distracted by the hand of God, a ray of light falling over the scene. The seemingly static figures have a sparkling verve, their cheeks flushed, their gaze piercing. Attired in wine reds and silvery whites, overlaying plum and gray robes, the saints stand at attention, crosses in hand. The angels are comparably pallid, dusted in cool grays. The Christ child is foregrounded here, his luminous halo silhouetted against the Virgin’s onyx-black gown. The scene is conspicuously quiet, as if holding its breath.

When Achi saw the icon for the first time, she was brought to tears. “It’s an image I’d studied in textbooks since I was nineteen,” she remembers. But encountering it up close was “emotionally charged,” so vivacious is its coloring. This is a painting that holds you, spellbound, like a distractingly beautiful face.

An Egyptian wool icon, hung opposite in the show, is comparably lush. The superbly rendered sixth-century work of cobalt blues and russet reds depicts the Virgin and Child ringed by bursting pomegranates and peaches, arabesque tulips and interlocking leaves. It’s a rippling scene, as jaunty as any allegro score.

No less enchanting are the love stories dotted throughout the show. In one, a satyr, or woodland spirit, and a maenad, a follower of the free-spirited Dionysus, are locked in a lyrical embrace. The fourth-century Egyptian textile, originally part of a larger work, is entrancing. The satyr, dressed in a bespeckled green cloth, holds the maenad in his arms, her gauzy pink shawl fluttering in the wind. They hide beneath a green-blue braided arcade. The two are alone: For them, no one else exists.

Across the way is a grand wooden chest from Nubia, or modern-day Sudan. Inlaid with ivory figures, the bridal gift teems with symbols of fertility and prosperity: all the better for the newlyweds. The work is spirited, ecstatic even. The eye has nowhere to rest. “It’s very erotic,” a woman said to her friend in the galleries. Indeed, it is: The minute ivory figures are uniformly nude, some contorted, others striking classical poses: Nothing is off limits for the young couple.

For those less lucky in love, there’s always magic. In the catalog is a Coptic spell to win a woman’s heart. It requires, among other things, mixing herbs with the frothy saliva of both a black horse and a bat, then burying the concoction under the door of the beloved, and, finally, calling on an unnamed being for “the sake of a heartfelt love.” The intricately conceived text, peppered with indistinct figures and labyrinthine patterns, is one of the many charms of the show, so close is it to the people who lived and moved through these cities. Love exists here, just around the corner.

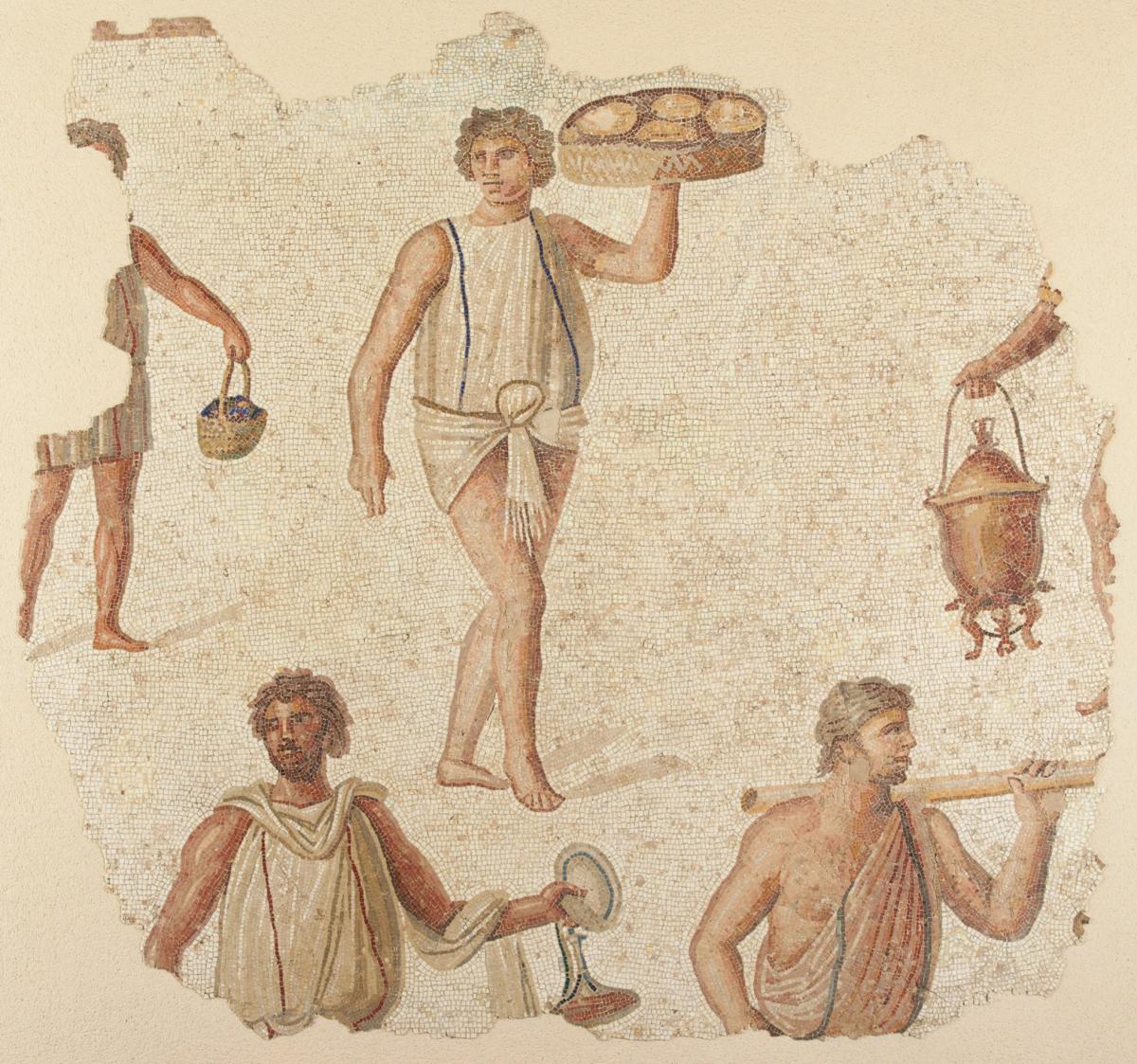

That spirit of anticipation brims over in one of the show’s mosaics. The second-century work, from Carthage, claims its own wall in the exhibition. It’s no surprise: The dazzlingly arranged picture is unlike any other in the galleries. Servants carry wine and overflowing baskets to a banquet, out of frame. The focus here is on the preparations, the delightful stirring just before the doors open: Something spectacular is afoot. The servers, clad in sand beige striped with crimsons, navy blues, and pistachio greens, are in mid-step: There is work to be done.

In the show, work is done by flesh and blood people, as in a wonderful aside in the catalog provided by a colophon, or printer’s note, from a ninth-century Coptic text on bodiless beasts. The scribe confesses, “Bear with me and my feeble little handiwork, for I am not yet very skilled.” You can almost see the dejected copyist, his work perfectly imperfect, the ink already dry.

That kind of self-denial runs through the show. In a series of terracotta tiles, deftly installed in one corner of the exhibition, is depicted the Old Testament story of Abraham almost sacrificing his son, Isaac, a razor-sharp sword held high above his head; another shows Daniel in a den of lions, his body a jagged stick figure beneath one of the gargantuan beasts. Salvation here is hard won.

A diptych of Saint George and the Virgin and Child, a few rooms on, is similarly pointed. The Ethiopian work, dated to the late fifteenth, early sixteenth century, is alive with fanciful pearl grays and sage greens, set against a rich coral ground. Saint George, perched on a brilliant-white horse, slays a thin, scallop-scaled dragon, slithering between the steed’s legs. Below is a body, sliced into neatly arranged pieces, a gesture to the saint’s decapitation, in 303 CE, for refusing to renounce his faith.

The gripping scene brings to mind the writing of Saint Augustine, the fourth-century bishop of Hippo, in present-day Algeria. In his Confessions, the philosopher-theologian expounds lucidly on the trials of the spirit: “Be not vain, my soul, and take care that the ear of your heart be not deafened by the din of your vanity.” His mind stirs beautifully on the page. He finds, by the work’s end, that it is only in the act of searching that he will arrive at a lasting peace: “Let us rather ask of you, seek in you, knock at your door,” he proclaims, echoing a pronouncement in the Gospel of Matthew. “Only so will the door be opened to us.”

A Nubian dignitary walks through that door in one of the show’s wall paintings. In the towering work, dated to the mid twelfth century, the ruler stands before Christ, who offers a blessing. There’s a delightful grace about the men, their robes studded with flecks of rust reds and metallic grays. The two are firmly rooted, statuesque: No one and nothing can rattle them.

“This is not one story,” Achi says, reflecting on the show, “but multiple histories.” Some are heart-rending, others fantastical, but all are suffused with beauty.

In one of the final rooms of the exhibition is an exquisite array of Ethiopian processional crosses. The finely rendered staffs catch the light, glittering. Installed alongside are a set of healing scrolls. The texts, written to cure the sick and ward off demons, are patterned with coiled illustrations, one a ring of faces. The scrolls mystify, even as they enchant.

Yeats ends his poem on an auspicious note. When the speaker passes into the next life, we learn, he will live on as a Grecian work of gold. Or he will sing, bird-like, to the rulers of Byzantium “of what is past, or passing, or to come.”

“Africa & Byzantium” seems an exhibition for our age, a reminder that any story worth telling will remain so, today, tomorrow, and for all time.