When the writer Martha Gellhorn died in 1998, her obituaries focused on two things. One was her work as one of the twentieth century’s most prolific war correspondents. The other was her brief stint as Ernest Hemingway’s third wife. It’s probably best that she wasn’t around to read these notices, which ran in major news outlets both in the United States, where she was born, and in England, where she lived during her later years, and where she finally chose to end her life, by suicide, at the age of eighty-nine. She had mixed feelings about the journalism that had been her life’s pursuit. And all the references to Hemingway would have only annoyed her.

She didn’t like to discuss her ex publicly. “I was a writer before I met him, and I have been a writer for 45 years since,” she once complained. She was correct on both accounts. Gellhorn was twenty-eight, an experienced reporter and the author of two books, when she met Hemingway. She was also adventurous and beautiful, and he was famous and married, and so the details of their early romance—set against the backdrop of the Spanish Civil War—are simply too good to leave out. Like the part about how they met at a bar in Key West and discussed writing, and politics, and hurricanes. Or the way they traded letters in the months that followed. (“Are we or are we not members of the same union? Hemingstein, I am very very fond of you.”) Or the way she eventually followed him to Spain in the spring of 1937. To get into the country she crossed over the border on foot at Andorra with fifty dollars and a knapsack and a bag of canned food. When she arrived at the Hotel Florida in Madrid, where the shells were falling, Hemingway greeted her with open arms and the words, “I knew you’d get here daughter, because I fixed it so you could,” which only in hindsight would seem ominous. With experience in combat and press credentials from the North American Newspaper Alliance, Hemingway had a clear reason for being in Spain. Gellhorn’s role—at first—was murkier. She had a “special correspondent” pass that she had wheedled out of a friend at Collier’s, her biographer Caroline Moorehead writes, but that wasn’t the same thing as having a job. Her trip across the Atlantic had been funded by an article she wrote for Vogue, titled “Beauty Problems of the Middle-Aged Woman,” an assignment that involved testing out a chemical peel that, she was convinced, had ruined her skin. It was an experience that had resolved her, she told a friend, to become “a great writer and stick to misery which is my province and limit my reforming to the spirit and the hell with the flesh.”

The next piece she published was titled “Only the Shells Whine.” “At first the shells went over,” it began. “You could hear the thud as they left the Fascists’ guns, a sort of groaning cough; then you heard them fluttering toward you.” Her article, which was published in Collier’s in July 1937, provided readers with little information about military tactics, but it was filled with the sights and sounds of a city under siege. “I cannot analyse,” Gellhorn would write years later. “It is not my bag.” She had roamed around Madrid, interviewing civilians, taking obsessive notes about the things she had witnessed, and then she had hammered them out onto the page with a steely precision—her “amazingly unfeminine” style, is what Graham Greene called it:

A small piece of twisted steel, hot and very sharp, sprays off from the shell; it takes the little boy in the throat. The old woman stands there, holding the hand of the dead child, looking at him stupidly, not saying anything, and men run out toward her to carry the child. At their left, at the side of the square, is a huge brilliant sign which says: GET OUT OF MADRID.

“I had no idea you could be what I became, an unscathed tourist of wars,” Gellhorn wrote in her first introduction to The Face of War. The book is a collection of her reporting, more than 30 articles organized chronologically into repetitively titled sections (“The War in Finland,” “The War in China,” “The War in Java”). Misery may have been her province, but her time in Spain was not without its thrills, especially as her work found readers and she found her footing as a correspondent. She rode to the front with Hemingway—who called her the bravest woman he ever met. She ate terrible wartime food and shared drinks with the other journalists and writers at the Hotel Florida—a cast of characters that included Virginia Cowles, Robert Capa, John Dos Passos, and Antoine de Saint-Exupéry. Life was filled with an invigorating sense of danger, “a feeling of disaster, swinging like a compass needle, aimlessly, over the city” and the conviction that she was fighting for a righteous cause by exposing the horrific acts committed by Franco’s Nationalist forces. “We knew, we just knew that Spain was the place to stop Fascism,” Gellhorn would later tell the journalist Phillip Knightley. “It was one of those moments in history when there was no doubt.”

As a result of this reluctance to concede anything to the enemy—especially not the moral high ground—Moorehead writes that Gellhorn, along with many of her fellow journalists in Spain, “walked a thin and nervous line between truth, evasions, bias, and propaganda.” She had no use for the “notion of objectivity,” the journalist Rick Lyman wrote. What she did have was an instinct for the surreal details of war, their visceral horror, their occasional beauty, as well as their dark humor:

An aviator came down from the fifth floor. . . . A shell fragment had hit his room and broken all his toilet articles. It was inconsiderate; it wasn’t right. He would now go out and have a beer. He waited at the door for a shell to land, and ran across the square, reaching the café across the street just before the next shell. You couldn’t wait forever; you couldn’t be careful all day.

“I cannot tell you,” Eleanor Roosevelt wrote to her readers of “My Day,” “how Martha Gellhorn, young, pretty, college graduate, good home, more or less Junior League background, with a touch of exquisite Paris clothes and ‘esprit’ thrown in, can write as she does.”

She also wrote fiction, although this fact is easy to lose track of in all the too-incredible-to-be-real biographical details. During the downtime between wars, she published five novels, 14 novellas, and two short-story collections. Fiction was what she loved, it had substance and staying power, unlike the transient articles she pounded out for her editor’s deadline. “Books matter,” she once said, “but magazines are for people on trains.”

The fiction she wrote was good. It was not, unfortunately, as good as Hemingway’s. As the mistress, and then the wife, and then the former wife of one of America’s most influential stylists, she was to be forever haunted by comparisons. Reviewers who read her pared-down prose accused her of being under the “Svengali spell” of her husband and complained that her stories were too “journalistic.” She had her own strengths as a writer, Moorehead observes, and they were the inverse of Hemingway’s. He wrote better novels, but her journalism surpassed his. This likely had something to do with the “hard, shining, almost cruel honesty [of her] work,” as one writer for the Guardian has described it. She was not seduced by the drama of battles; she did not attempt to elevate what she had witnessed into art. Her articles used the first-person “I,” but they were about her subjects, not about herself. Hemingway, filing a story from Madrid in April 1937, did not always successfully escape these temptations:

A high, cold wind blew the dust raised by the shells into your eyes and caked your nose and mouth, and, as you flopped at a close one and heard the fragments sing to you on the rocky, dusty hillside, your mouth was full of dust. Your correspondent is always thirsty, but that attack was the thirstiest I had ever been in. But the thirst was for water.

Gellhorn understood her limitations as a writer because she could often—though not always—turn that hard honesty upon herself. “Deviously, everything I have ever written has come through journalism first, every book I mean,” she wrote to Hemingway. “I have to see before I can imagine. I feel and act like a hardworking stenographer and I feel kind of happy about it in a grubby hardworking way. . . . It is an honourable profession. . . . Even when not pleased with what I write, I am immensely pleased with what I have understood.”

Just as Hemingway, she was disciplined in her writing, even when the slow and tedious work of producing a book sometimes overwhelmed her. “The empty pages ahead frighten me as much as the typed pages behind,” she once confessed. Following the victory of Franco’s army, Gellhorn joined Hemingway in Cuba, where the two writers, both exhausted and disillusioned, decided to give up reporting about war and turn, instead, to writing novels about it. Life on the island suited Hemingway, who read, drank with friends and admirers, and embarked on fishing expeditions in his boat, Pilar. In the mornings, he vanished into the bedroom to write with a concentrated focus that took him somewhere far away, “exactly as if he were dead,” Gellhorn observed admiringly, “or visiting the moon.”

Her own favorite place to write was outdoors in the sunshine, preferably while naked. The house in Havana, with its pink painted walls, its jacaranda flowers and hummingbirds and nearby beaches was idyllic—too idyllic—and inevitably she became restless. It was 1939 and she was unable to ignore the storm clouds in the distance.

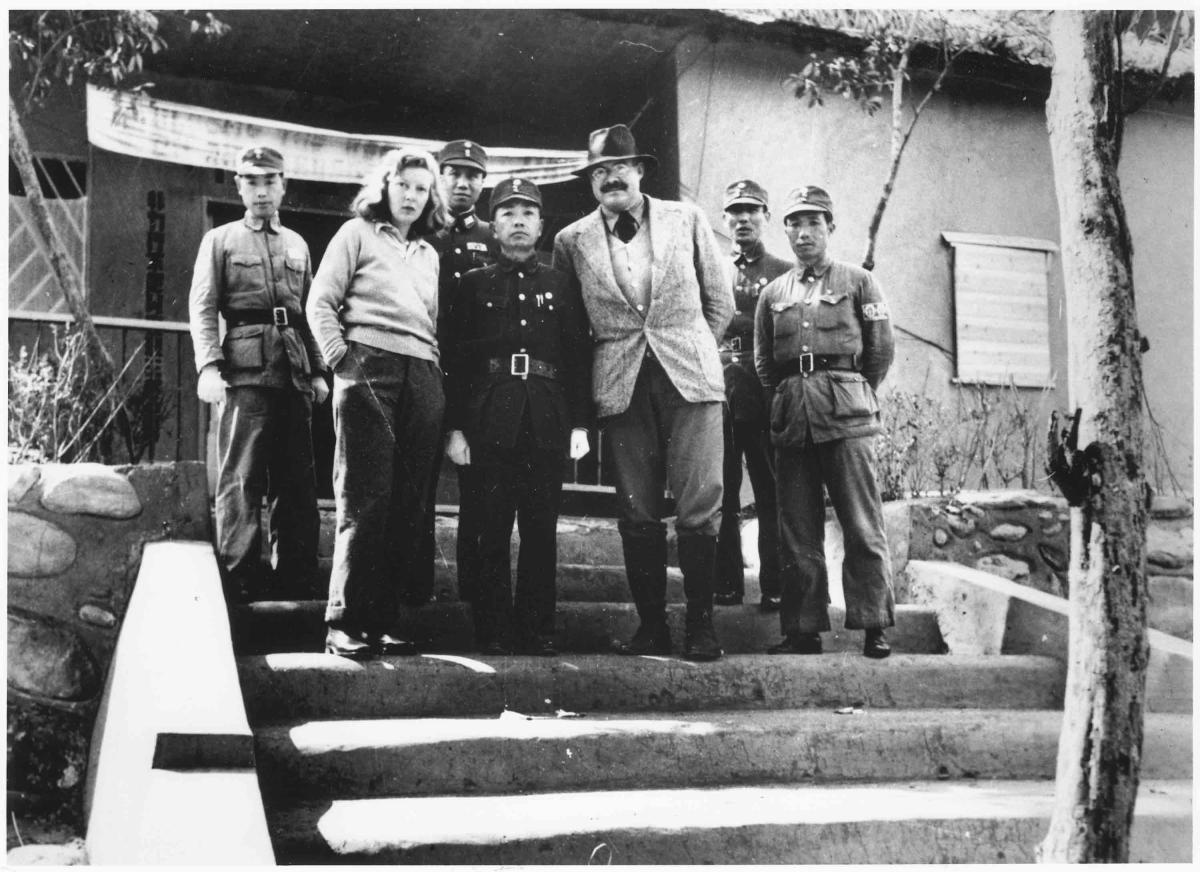

To Hemingway’s dismay, she began accepting assignments again. When asked by Collier’s to report on the Russian invasion of Finland in October, she first looked up Finland on a map, and then she said yes. (“It’s going to be terrible,” she reported back to Hemingway. “The people are marvellous, with a kind of pale frozen fortitude.”) Not long after she and Hemingway were married in November 1940, she made the mistake of talking her grudging new husband into accompanying her on a trip to cover the war in China: “I went on wheedling until he sighed gloomily and gave in,” she recounted later in an essay titled “Mr Ma’s Tigers” that appeared in Travels with Myself and Another. “That was scandalous selfishness on my part, never repeated. Future horror journeys were made on my own.”

The journey was indeed a horror, complete with cholera outbreaks, bug-infested lodgings, and a near-death experience on an airplane. And it was capped off when Gellhorn developed a contagious fungal infection—dubbed “China Rot”—on both of her hands. A Chinese doctor prescribed a stinking salve, which she was forced to slather on and keep covered with a pair of motorman’s gloves she could not remove, even while showering.

Hemingway had been dead for 17 years when Gellhorn published Travels and she refused to put his name into her essay. (She designated him “U.C.” for “Unwilling Companion.”) Still, the piece offered a glimpse into their relationship and revealed the cutting sense of humor the two of them shared, even under their miserable and sometimes ludicrous circumstances:

‘What’s in here?’ I said, shaking the jug.

‘It’s called spring wine,’ U.C. said evasively. ‘It was all Mr Ma could get. Considered very high class, the Chinese drink it as an aphrodisiac.’

‘What’s in this jug?’

‘M., are you sure you want to know?’

‘Yes.’

‘Well, snakes. But dead. M., if you throw up, I swear I’ll hold it against you.’

The most surprising thing about “Mr Ma’s Tigers”—aside from how funny it is—is how skillfully Gellhorn conjures up these long-ago moments of mocking affection and thwarted tenderness—especially given the bitter feelings on both sides as their relationship deteriorated. “Are you a war correspondent or wife in my bed?” Hemingway cabled her a few years later, while she was deep in the action of Europe, making her way, as she always did, on her wits and her looks. “He got his answer on D-Day, June 6, 1944,” the reviewer Brenda Maddox wrote, “when she stowed away on a hospital ship and landed on Omaha Beach soon after the invasion.” In 1945, she became the only one of his four wives to leave him, and he never forgave her for it.

Gellhorn’s D-Day feat remains one of her most famous, most likely because it serves as such an obvious example of both the derring-do she was known for and of the ingenuity she used to skirt around the restrictions that were placed on female reporters at the front during World War II. (She was later arrested by British military police for entering France without the appropriate authorization.)

Her most harrowing experience, however, came the following spring when she walked into the newly liberated Dachau. Word about the atrocities committed at the concentration camps had been leaking out, and the more than 30,000 prisoners left behind in Dachau by Germans fleeing the U.S. Army provided irrefutable evidence of what had been done. For the journalists who arrived on the scene, there was the near-impossible task of describing it. In her Collier’s article, “Dachau,” Gellhorn chose her words with care:

Behind the barbed wire and the electric fence, the skeletons sat in the sun and searched themselves for lice. They have no age and no faces; they all look alike and like nothing you will ever see if you are lucky.

The piece, like all her reports, is meticulously written and matter of fact in its tone. “In Dachau,” she told her readers, “if you want to rest from one horror you go and see another.” But her rage percolated through her otherwise restrained language. Toward the end of “Dachau,” she noted with grim satisfaction the “clothed healthy bodies of the German soldiers” who had been shot when the Americans entered the camp. (The killing of German guards by soldiers who liberated the camps would later become the subject of a U.S. military investigation.) It was, she said, “the first time anywhere one could look at a dead man with gladness.” If ever a situation warranted cruel honesty, this was it. Later she would write, “I reported what I saw, and hate was the only reaction such sights could produce.”

Hate was also, one assumes, easier to express than anguish. More than two decades after Dachau, Gellhorn would admit that her experiences there had inflicted a kind of moral injury that caused her to “[suffer] a lifelong concussion, without recognizing it.” She told her friend Hortense Flexner, “Looking back, I know I have never again felt that lovely, easy, lively hope in life which I knew before, not in life, not in our species, not in our future on earth.”

In the months that followed, Gellhorn became “consumed,” Moorehead writes, by a need to learn everything she could about what had happened in the concentration camps. She attended the trials at Nuremberg, where she sat in the audience and studied the faces of the men who were responsible for the things she had witnessed, and she pinned each one to the page with a sentence or two. Hermann Goering had a “terrible mouth [that] wore a smile that was not a smile, but only a habit his lips had taken.” Wilhelm Frick’s “gray-blond cropped head and lean, horsy face bent forward to listen, almost as if he were a visitor.” Baldur von Schirach “looked like a woman who has suffered from imagined ailments all her life and blackened her family’s existence with complaints.” They were all “strange faces” she wrote, and, ultimately, they told her “nothing.”

It was useless to go on telling people what war was like,” Gellhorn wrote in The Face of War. “Since they went on obediently accepting war.” For the following 20 years, she steered clear of geopolitical conflicts and lived in a state of self-imposed but restless peace. She moved around; she adopted and raised a son; she fell into and out of several relationships, eventually marrying and divorcing one more time before she swore off marriage for good. She devoted the majority of her attention to her beloved fiction.

The real question is why she went back. In 1966, she was fifty-eight years old, practically geriatric by the standards of the profession, when she resumed her work as a war correspondent in Vietnam. Her contacts at her previous publications had dried up, but she convinced the Manchester Guardian to take six of her pieces, provided she covered her own expenses. When she arrived in Saigon, Moorehead says, she found a generation of reporters who had grown up during the time she’d been away, many of whom had never heard of her—although they admired the older woman’s still-phenomenal looks and sense of style. “Other women in Vietnam looked terrible,” recalled the British journalist Clare Hollingworth. “Martha looked terrific.” It was unclear to them what, exactly, she was doing there.

She was doing what she’d always done—wandering around the city, skipping press briefings, and opting, instead, to visit orphanages and refugee camps and hospitals, where she detailed the horrifying civilian casualties inflicted not by the Viet Cong but by the Americans’ military tactics. Freed from World War II-era censorship and whatever notions she’d once held about righteous wars, she was free to declare her outrage both about the suffering she saw and the governments that caused it. Her reports from Vietnam, as well as Central America, which she traveled to in the 1980s, are among some of her most scathing:

In the areas called Free Air Strike Zones, or some such jargon, there is no warning and people can be bombed at will day or night because the area is entirely held by Vietcong, and too bad for the peasants who cling to their land which is all they have ever known for generations.

She was back to telling her readers, once again, however uselessly, what war was like. She was trying, however futilely, to keep them from looking away. "A friend once wrote to ask her if she was ever afraid,” Moorehead writes. “‘No,’ she replied. ‘I feel angry, every minute, about everything.’” So maybe that’s as good an answer as any. She understood the tragedies of the war better than most people, but unlike most people, she was unable to accept them.

She couldn’t accept old age either. She worked on into her ninth decade, in spite of what was diagnosed as macular degeneration, which steadily eroded her eyesight and made it increasingly difficult to read even her own work. At the age of eighty-five, over drinks, she sweet-talked Granta editor Ian Jack into giving her an assignment—a piece she pitched him on the murders of Brazilian street children—and then she set off for South America. The story she produced, despite her painstaking efforts, was not of a publishable quality, and it left Jack in the “unhappy position,” Moorehead writes, of having to turn down the legendary Martha Gellhorn. Her Brazil piece would prove to be the “last long investigative reporting she attempted.”

Gellhorn pressed on, but a few years later, as her health grew worse, she offered a characteristically blunt assessment of her situation to a friend. “There are two things the matter with me,” she said. “One, my body is too old, I can no longer do what I want to do. I am as close to sedentary as I can get without actually being tied to a chair. Two, I am bored.” For Gellhorn, boredom was, literally, a fate worse than death. She began to make her final plans, and on February, 14, 1998, she swallowed a cyanide pill in her apartment in London. She left the windows open and all the lights ablaze.

Moorehead writes that a resurgence of interest in Gellhorn marked her final years. She developed a fan club of younger editors and writers, and publishers again “began to notice and admire her work, praising her persistence and her intelligent eye.” A year after her death, her 1948 story “Miami-New York” was selected to appear in Best American Short Stories of the Century alongside the stories of literary heavyweights such as Willa Cather, William Faulkner, Saul Bellow, and, of course, Ernest Hemingway.

“Miami-New York” takes place on an overnight flight during which two strangers seated next to one another, a Navy lieutenant and the wife of a soldier away at war, share a kiss and a fleeting connection that brings them briefly together—and then leaves them dissatisfied and alone once again as their plane reaches its final destination. War is both far away and overwhelmingly present, and Gellhorn’s story precisely captured, the anthology’s editor John Updike wrote in his introduction, “the feel of wartime America—the pervasive dislocation that included erotic opportunity, constant weariness, and contagious recklessness.”

Wartime also included, as Gellhorn knew, the painful recognition that sacrifice did not guarantee any sort of catharsis or greater understanding. “War was always worse than I knew how to say—always,” she said. In the end, she could only really ever follow the old adage about writing what you know. And by doing so, she left behind something that was hard to look away from and hard to forget.