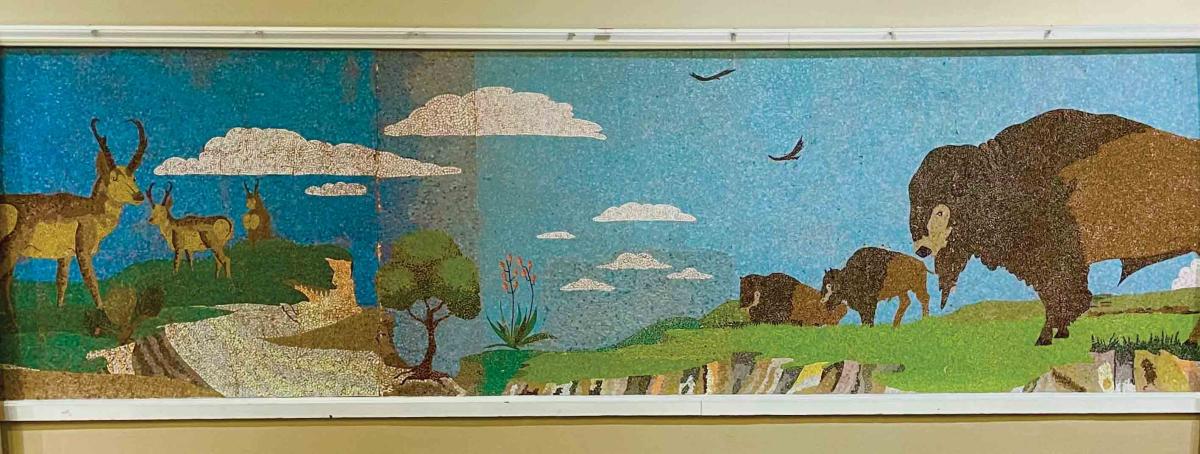

In the lobby of the downtown Wichita branch of Southwest National Bank, on the wall behind and above the clear plastic barrier separating customers from tellers, there stands roughly 100 feet of a painted mural separated into three panels. In between each panel, cameras protrude from the wall, watching.

The customers watch right back. Bank employee Carolynn Francis says they often ask about The Spirit of Kansas, a 1915 mural by Arthur Sinclair Covey. For Francis, over time, the mural faded into the background of her daily existence. But in April she spied a copy of a copy of a handout about the mural.

“I Googled it,” she says.

To engage curious residents like Florence, who want to know more about the art around them, Dave Loewenstein has dedicated much of his career to encouraging communities to appreciate and participate in public art. “This is a great story about how murals can continue to have an impact even a century after their creation,” Loewenstein says.

Originally from Evanston, Illinois, Loewenstein is not only a promoter of murals, he is a mural artist in his own right. He earned his first solo gig as a “surface artist” while working as a farm apprentice in upstate New York.

“I painted the side of a semitrailer that we were using to store potatoes and other root crops in the late fall. . . . I liked the idea of this not being in an art gallery,” he says.

Loewenstein headed to Kansas with the intention of becoming a small-scale farmer. That path also brought him to graduate school at the University of Kansas to study art. He became a landscape painter focused on the 1980s farm crisis. But something gnawed at his gut. He began to question the merits of making a piece of art simply for his own enjoyment or that of a select few people.

“I had other notions about what art could do,” Loewenstein says.

He found himself inspired by José Clemente Orozco, Diego Rivera, and other great artists of the Mexican mural renaissance, who themselves inspired the 1930s Works Progress Administration’s mural program.

“There are still 20-some murals in the state that came out of this New Deal-era program,” Loewenstein says.

In the bowels of the University of Kansas art library, he discovered Toward a People’s Art, a book that pointed him toward a different kind of mural art.

“I could see right away that these weren’t Thomas Hart Benton or Diego Rivera murals. These were murals made by communities,” Loewenstein says.

The book described communities and neighborhoods banding together to create public art. A collection of people, some with vast experience, others who had never picked up a brush, worked together to conceive and carry out a collective vision. To Loewenstein, it was a radical idea, but one that piqued his interest.

As he read through the book, he came to a page with a black-and-white photo showing children and adults painting a mural together. It looked vaguely familiar. The caption read, “Miller School mural. 1975. Evanston, Illinois.” Loewenstein attended that very school. And in the photo, with a much fuller head of hair, there he was.

“After thinking about it, I did remember, vaguely, being super excited about this, and terrified, because you are painting on a wall and can’t fix it,” Loewenstein says.

The community mural movement fixed itself in the art world’s imagination in the 1960s in Chicago, with artists like William Walker, John Pitman Weber, and Caryl Yasko helping neighborhood residents navigate art projects.

“But the designs were developed by regular folks in neighborhoods. And they depicted what was of interest to them. A lot of these projects . . . were painted collectively,” Loewenstein says.

Father Blaine Schultz, a monk and music professor at Benedictine College in Atchison, Kansas, told Loewenstein that, as a young man, he watched in awe as muralist Jean Charlot painted a fresco at St. Benedict’s Abbey in town. When Charlot noticed Schultz watching, he beckoned him to help paint the mural.

Loewenstein applied this concept to his own work in Kansas. In 2002, the town of Hutchinson invited Loewenstein to create a large mural in a local park. He invited the community to join in the action.

“I very intentionally don’t come with an idea of what the mural is going to be,” Loewenstein says.

The work, called Ad Astra, depicts various people observing constellations. When the assembled local artists realized they didn’t know very many constellations, they gave themselves permission to create their own.

Finding and learning about murals in Kansas was a nearly impossible task in the early 2000s. Locations, artists, origins, and backstories were often a mystery. Loewenstein took it upon himself to fix that problem. Along with Lora Jost, he wrote Kansas Murals: A Traveler’s Guide. The book describes 90 noncommercial murals across the Sunflower State. He now gives talks on the state’s murals for Kansas Humanities.

Loewenstein is sometimes asked if murals will become obsolete in an age of technology.

“As we become more and more tied to our phones and computers, as work and social life are drawn into the glow of our devices, we’ll hunger for a stable and steady image that we can contemplate without the seduction of a million other things to look at,” he says.

Back at Southwest National Bank, Larry Aginar, senior vice president of risk management, gazes at the three panels of The Spirit of Kansas and wonders what the figures depicted are thinking about.

“I look at specific images and imagine what it would be like to be there,” Aginar says.