Write if you will: but write about the world as it is and as you think it ought to be and must be—if there is to be a world.

Write about all the things that men have written about since the beginning of writing and talking—but write to a point. Work hard at it, care about it.

Write about our people: tell their story. You have something glorious to draw on begging for attention. Don’t pass it up. Use it.

—Lorraine Hansberry, To Be Young, Gifted, and Black, New York, May 1964.

I hope that I can be forgiven for having been so nervous. Standing next to Tracy Heather Strain, director of the remarkable 2018 film Sighted Eyes/Feeling Heart, the first feature-length documentary of the life and work of Lorraine Hansberry, author of the groundbreaking 1959 play A Raisin in the Sun, I found myself surprised—and a bit unnerved—by the moment’s many contradictions. Strain’s documentary had just been screened to a full and eager crowd in the Thompson Room of Harvard University’s lovely Barker Center. It is a large, comfortable, wood-paneled space dominated by a bronze statue of the Greek god of time, Chronos; a large, ornate grandfather clock; a nearly life-sized portrait of Theodore Roosevelt (hidden for the evening by a movie screen that descended effortlessly from a trap in the ceiling); and a grand ornamental fireplace on which squats a glum bust of none other than John Harvard himself. It is a monument to the fantasy of a presumably lost “old Harvard.” The room’s many trappings work to remind those who enter it that this space has been secured at a great price and that few of the people who commissioned the teak, marble, and velvet that give the place its grandeur could have imagined the scene of two African-American intellectuals arranged before a multiracial, multigenerational collection of women and men, students and workers, professors and activists, straights, queers, and trans persons, all with their hands raised, eager to hear from Strain what more she could tell them about the long dead writer and activist Lorraine Hansberry.

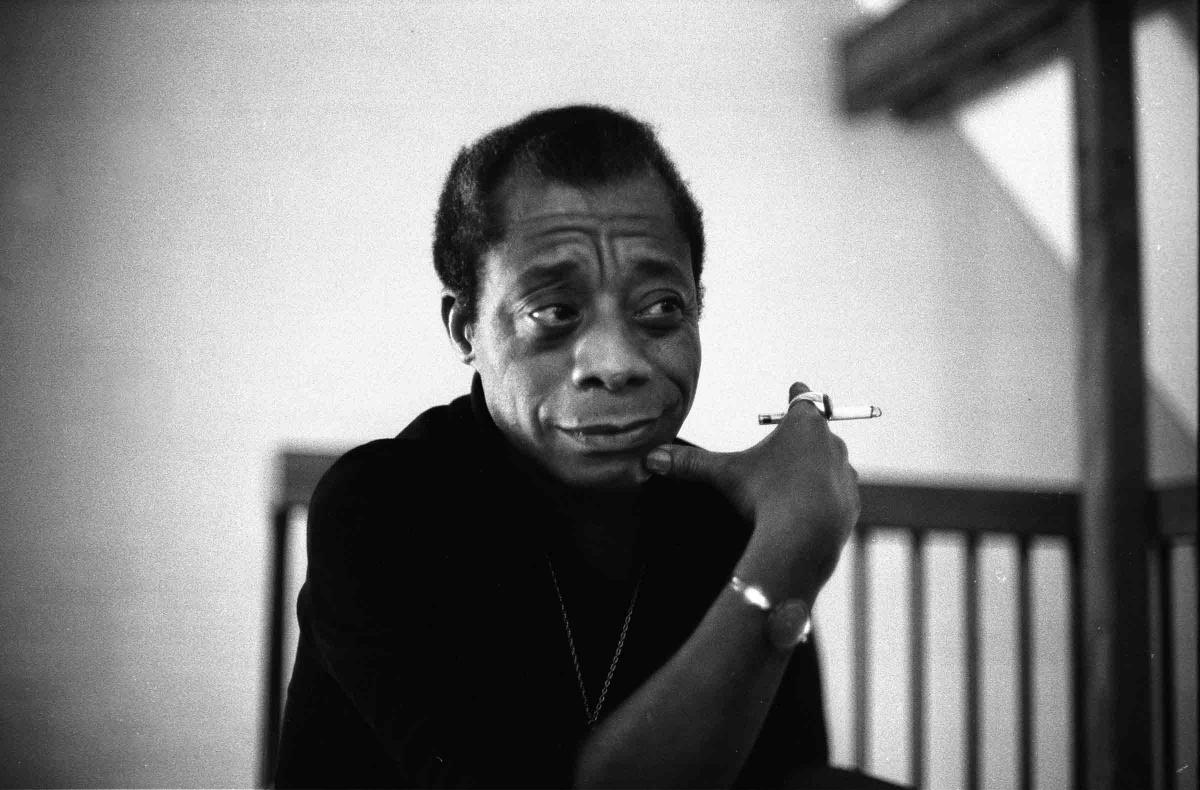

It seems, in fact, that, as with her dear friend the author James Baldwin, Hansberry is having a curiously vibrant renaissance some 54 years after her death, at the age of thirty-four from pancreatic cancer, on January 12, 1965. Sighted Eyes/Feeling Heart has had a vigorously successful run. First appearing on January 19, 2018, in the PBS documentary series American Masters, the film went on to win both a Peabody Award and an American Historical Association Film Award, while Strain received a 2019 NAACP Image Award for Outstanding Directing in a Television Movie or Special. Swimming alongside Sighted Eyes in this sea of adulation is Imani Perry’s equally impressive 2018 biography Looking for Lorraine: The Radiant and Radical Life of Lorraine Hansberry, which won the 2019 PEN/Jacqueline Bograd Weld Award for Biography, the Publishing Triangle Shilts-Grahn Award for Nonfiction, and designation as a 2018 New York Times Book Review Notable Book. There are, moreover, at least two additional biographies of Hansberry in the works.

The pressing, indeed needling, question, however, is, Why now? Why has Hansberry suddenly captured the attention of a generation of scholars and creative intellectuals who came of age in an era in which she was largely treated as a gifted—if somewhat old-fashioned—playwright whose major work championed long since established and settled ideas about the aspirations of a decidedly integrationist and none-too-radical black middle class? What explains the social complexity of the rooms in Cambridge, Chicago, New York, Boston, Paris, Melbourne, Washington, D.C., Providence, Harrisburg, Honolulu, Philadelphia, Brooklyn, Pittsburgh, Toronto, Atlanta, Stockholm, Detroit, and Houston, where many people greedily consumed Strain’s film and sat captivated by Perry’s lovely prose?

The easy answer to this question is simply to note the fact that we are all intrigued by the very complexity and contradiction that so perplexed us that evening in the Thompson Room. It is now well known that though Hansberry was married from 1953 to 1964 to the editor, songwriter, and producer Robert Nemiroff, she also identified as lesbian, writing two letters to the early lesbian rights journal The Ladder. “I’m glad as heck that you exist,” she wrote in May of 1957. “You are obviously serious people and I feel that women, without wishing to foster any strict separatist notions, homo or hetero, indeed have a need for their own publications and organizations.” Still, even as I am infinitely grateful for the difficult and largely unheralded work that Hansberry’s friends and admirers, particularly Nemiroff, have done to maintain the archival materials that have allowed us this glimpse into Hansberry’s identity, I believe that it is necessary that we push beyond simply naming Hansberry as a “closeted” lesbian in order to understand how her complicated personality actually impacted both her aesthetics and her politics. What is so fascinating about Hansberry is not so much the “secret” of her homosexuality as the fact that she was herself so very aware of the complexities of identity, sexual or otherwise, that underwrote her own subjectivity and those of the many communities to which she belonged.

Twelve years before the Stonewall insurrection of 1969 and decades before the theoretical advances loosely grouped under the rubric of “queer theory,” Hansberry understood that sexual and social identity did not—and perhaps could not—line up neatly with the ways in which we produce our social and affective lives. Perry reports a strikingly complicated pair of lists written on April 1, 1960, in two columns in Hansberry’s datebook. Under the heading “I like” she writes:

Mahalia Jackson’s music; my husband—most of the time; getting dressed up; being admired for my looks; Dorothy Secules eyes; Dorothy Secules; Shakespeare; having an appetite; slacks, my homosexuality; being alone; Eartha Kitt’s looks; Eartha Kitt; that first drink of Scotch; to feel like working; the little boy in “400 Blows;” the way I look; the way Dorothy talks; older women; Miranda D’Corona’s accent; charming women; and/or intelligent women.

In a column labeled, “I hate,” she adds:

Being asked to speak; speaking; too much mail; my loneliness; my homosexuality; stupidity; most television programs; what has happened to Sidney Poitier; racism; people who defend it; seeing my picture; reading my interviews; Jean Genet’s plays; Jean Paul Sartre’s writing; not being able to work; death; pain; cramps; being hung over; silly women; as silly men; David Suskind’s pretensions; sneaky love affairs.

The trick to understanding the complexity of these two lists is exactly to resist the urge to distrust them. Instead of attempting to wash away the grit left in one’s mind upon hearing that Hansberry likes her husband most of the time and then finding a few lines later that she also likes not only her lover, Dorothy Secules, but also Dorothy Secules’s eyes, we should try to accept Hansberry at her word. With a wit that is once dry and sober, Hansberry demonstrates the reality that contradiction is a universal aspect of the human condition, one that is not inherently toxic. The fact that she both likes and hates her homosexuality, likes charming and/or intelligent women, and hates her loneliness does nothing more than name Hansberry as a human, one with the clarity, sensitivity, and honesty, to see—and announce—the always ambiguous realities of life and then to place that ambiguity at the service of her art.

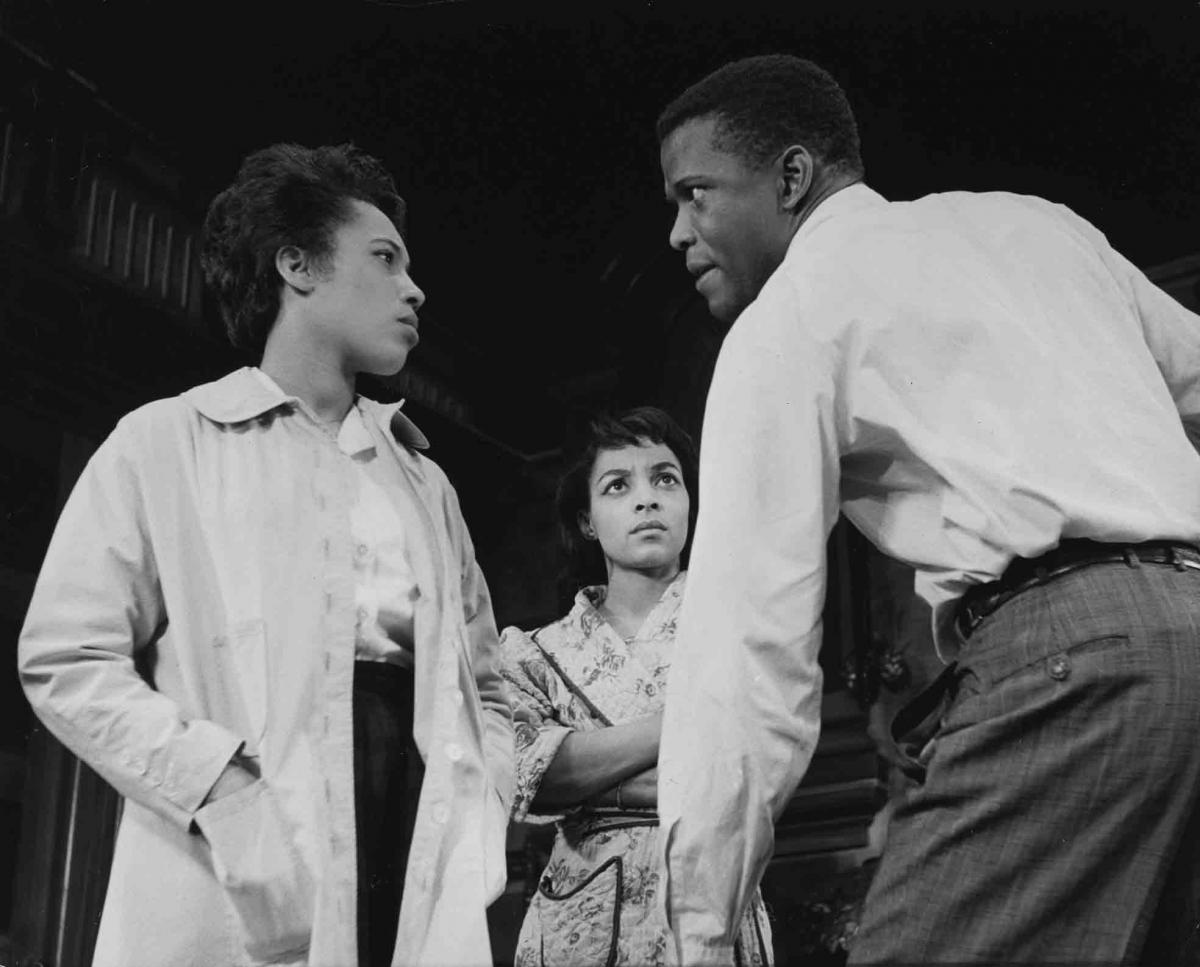

I rush to make this point because part of what has plagued Hansberry’s legacy is the seemingly unquenchable desire of her champions and detractors alike to both over—and under—analyze her work. After Raisin in the Sun debuted in 1959, making Hansberry the first African-American woman to have a play mounted on Broadway—and then the youngest American playwright, the fifth woman, and the only black woman to win the New York Drama Critics’ Circle Award—she seemingly fell head first into the particularly knotty and byzantine trap reserved for the successful and the famous. She was, that is, treated as a flat, two-dimensional thing, one that was presumably damned to announce time and again the logics and aesthetics of a first triumphant work.

It is important we remember that after her success with Raisin, Hansberry was met with derision and financial disaster following the October 15, 1964, opening of her second play, The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window. This piece treats boldly and without flinching the themes of ambiguity, confusion, and artifice with which Hansberry struggled throughout her career. Sidney Brustein is a leftist intellectual making his way as an unsuccessful writer in New York’s Greenwich Village. His wife, Iris, tires of the couple’s hand-to-mouth existence and eventually decides to move from working in the theater in order to make her way as a television actress. Her sister, Gloria, is a prostitute masquerading as a model. Nonetheless she takes a lover, Alton Scales, an African-American activist who attempts to convince Sidney to become involved in politics. Though Gloria eventually kills herself after Alton discovers the truth about her profession, very little else actually happens in the play. As a consequence, the work was broadly criticized as too long, too cerebral, and much too wordy. As with the novel Another Country, published two years earlier by Hansberry’s friend Baldwin, critics were dumbfounded and insulted that, instead of the type of straightforward morality play that they thought they’d seen in Raisin in the Sun, Hansberry had dared to produce a piece in which there were no easy answers nor clearly defined heroes, tragic or otherwise. With The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window, Lorraine Hansberry seemed to be saying that the future would be secured not by heroes but muddlers; that tomorrow is not a place in which we might finally achieve our fanciful dreams of a beloved community but instead a complicated, difficult, and sometimes dull space in which we will be forced to use all of our tools, including our tackiness, pettiness, fear, stupidity, clumsiness, loneliness, and lust in order to slouch toward an at least somewhat brighter tomorrow.

When we look at Lorraine Hansberry, we find ourselves at once delighted and repulsed by the fact that she seems to be not so remarkably different from the rest of us. While she longed for a world free of white supremacy, homophobia, patriarchy, and capitalist exploitation, she clearly understood that even though human life and subjectivity are always miraculous, they are infrequently noble. When she advises us to “write if you will: but write about the world as it is and as you think it ought to be and must be—if there is to be a world,” she is pointing us in the direction of a particularly flat and restrained understanding of both politics and aesthetics in which, even as we struggle for liberation and radical renewal, we must be mindful of the fact that the clumsy, workaday tools that we hold in our hands are the only implements of change that we have available to us.

In the encomium that Baldwin wrote about Hansberry after her untimely death, he spent considerable energy reminding us that the committed artist must always remain intimately tied to the social world that gave rise to her, even as this may (negatively) impact the quality, the reach one is wont to say, of her art.

One is not merely an artist and one is not judged merely as an artist: the black people crowding around Lorraine, whether or not they considered her an artist, assuredly considered her a witness. This country’s concept of art and artists has the effect, scarcely worth mentioning by now, of isolating the artist from the people. One can see the effect of this in the irrelevance of so much of the work produced by celebrated white artists; but the effect of this isolation on a black artist is absolutely fatal.

Here is where it becomes abundantly clear how profoundly Baldwin and Hansberry affected each other and how deeply each of them was committed to producing art suited to the exigencies of the black freedom struggle. Writing to her mother on January 19, 1959, from New Haven, Connecticut, on the eve of Raisin’s pre-Broadway premier, Hansberry mused simply that she believed that the work would “help a lot of people to understand how we are just as complicated as they are—and just as mixed up—but above all, that we have among our miserable and downtrodden ranks—people who are the very essence of human dignity.”

It is this keen sense of the nobility that exists even and especially among the most common of us that Hansberry insistently and aggressively presses forward in her oeuvre. In Act III of Raisin in the Sun, after the main character, Walter Lee Younger, has lost much of the insurance money meant both to pay for his family’s new home in the white suburb of Clybourne Park and for the medical education of his sister, Beneatha, his mother, Lena Younger, defends her son against her daughter’s wrath by invoking just this perception of graciousness and decency standing alongside—indeed within—failure and imperfection. “When you starts measuring somebody, measure him right, child, measure him right. Make sure you done taken into account what hills and valleys he come through before he got to wherever he is.” We can see just this belief system, this embrace of contradiction and fallibility shot through all of Hansberry’s work, from the headstrong and self-deluded Walter Lee to the frightened and myopic Sidney Brustein. It is perhaps best represented, however, in Hansberry’s posthumously produced play, Les Blancs, in which she corrects what she takes to be the two-dimensionality of Jean Genet’s 1958 farce Les Negres (translated into English as The Blacks) by building her story of African decolonization around three flawed and wounded brothers: Tshembe Matoseh, who returns from England to his native village for the funeral of his father; his gender non-conforming and presumably gay half-brother, Eric Matoseh, the product of the rape of his mother by a white colonist; and Abioseh Matoseh, the conservative oldest brother on the verge of becoming a Catholic priest. All three are unlikely antiheroes who are marred, if not exactly broken, by the systems that produced them. Yet each has a role to play in the disruption of the systems of colonial control and influence that dominate their society.

Hansberry demonstrated in every work she penned that she understood and accepted the idea that there is no path forward except through the grubby contradictions that so many of us shun. “American writers have begun to believe what I suspect has always been one of the secrets of fine art,” she argues. “There are no simple men.” I think that it is this sense of possibility, hope, and promise even in these particularly difficult and morally fraught times that attracts so many of us to Hansberry today. Though her life and career were cut tragically short, she continues to draw the pointed attention of critics, historians, documentarians, and adoring audiences alike precisely because she reminds us that even in our awkwardness, even as we stumble about and try to make sense of ourselves in rooms that were never intended to contain or comfort us, we nonetheless might take heart that it is exactly this sense of anxiety and embarrassment, this lack of simplicity, which we might (indeed must) utilize as we seek, in the midst of irritation and confusion, a way forward.

* This article was updated on July 19, 2019, to correct the dating of the end of Lorraine Hansberry's marriage to Robert Nemiroff. In 1964, Hansberry and Nemiroff obtained a divorce.