I was recently in a Northern California bookstore, where I noticed a stack of a new Library of America volume of Gary Snyder’s collected poems. It includes nearly every Snyder poem and translation as well as endless notes on his craft. The pages, as thin as those in a King James Bible, turn with ease to chronicle the lifework of a man whose hardscrabble training—years of outdoor work in the Pacific Northwest and study in Japan—has rooted his poems in a central theme: Nature is not apart from us. What Snyder has wanted is freedom from most of what he feels ails the American frontier: dogged possession not just of the land but of the spirit.

After many days of reading, I came upon this poem from Danger on Peaks, Snyder’s favorite volume.

Steady, They Say

Clambering up the rocks of a dry wash gully,

warped sandstone, by the San Juan River,

look north to stony mountains

shifting clouds and sun

—despair at how the human world goes down

Consult my old advisers

“steady,” they say

“today”

(At Slickhorn Gulch on the San Juan River, 1999)

(Gary Snyder, from Collected Poems, edited by Anthony Hunt and Jack Shoemaker. Reprinted with permission, Library of America, copyright © 2022.)

The speaker’s old advisers here are the classical Chinese and Japanese poets to whom Snyder dedicated years of study. The poem tries to reconcile our environment with the notion of purposeful choices anchored in the study of Buddhism. The rhythm of the poem unfolds naturally. We are hiking on a riverbed near Snyder’s home, wondering if there will be a moment of understanding. And then the answer: “‘steady,’ they say / ‘today.’” Things will work out—even if we cannot know how. The speaker’s old advisers have been here before.

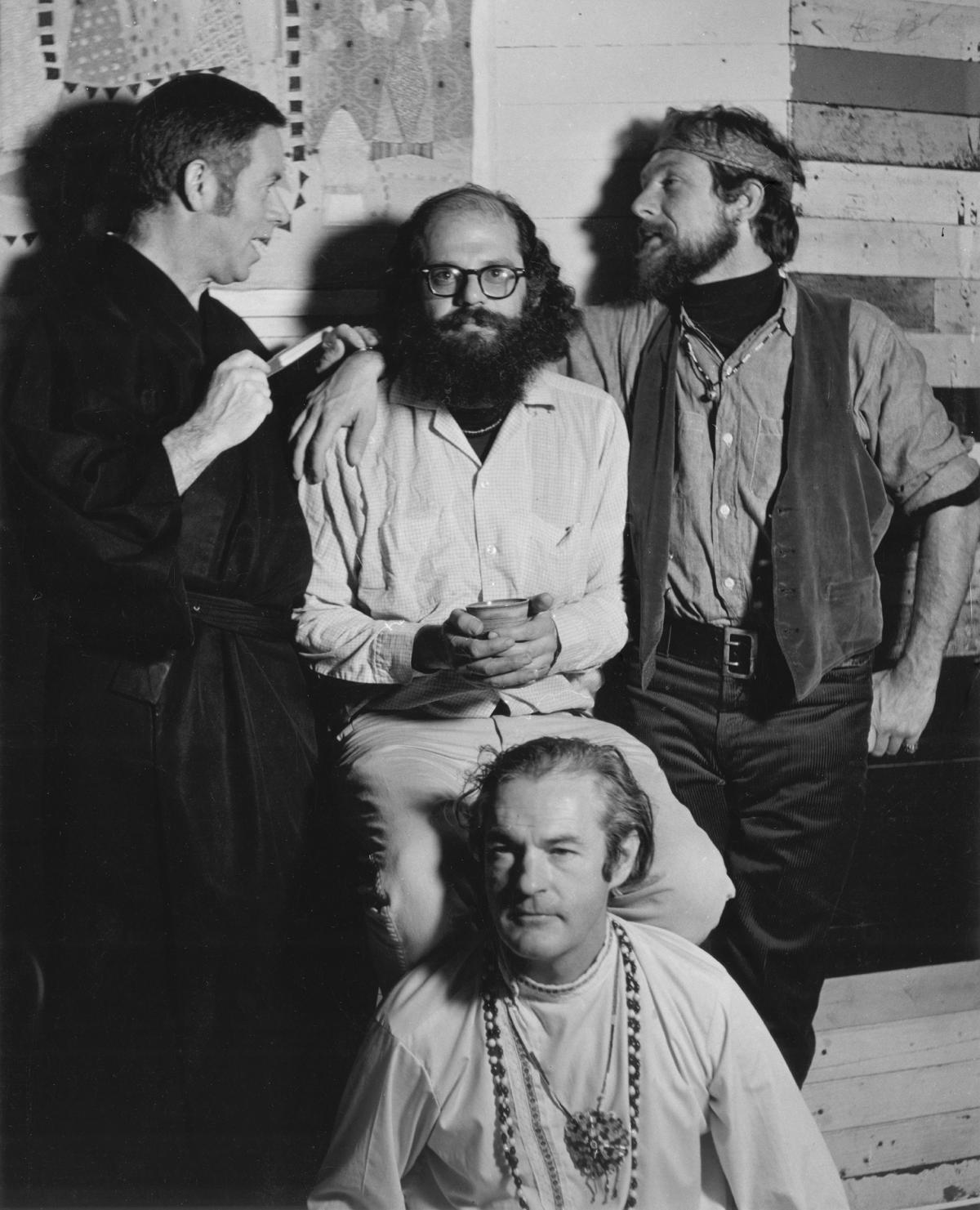

A long time ago, when I was in my twenties and Snyder, in his forties, was chair of the California Arts Council, I applied for a grant as a master poet. In spite of my being such a knucklehead, he took the high road and wrote me back, simply saying those grants were for established poets, not beginners. That was my first contact with the man who was making calls as chair of the arts council from a pay phone because there was limited access to utilities at his off-the-grid home, Kitkitdizze. He was also the same man who stayed up late working on the budget with then-governor Jerry Brown. Slowly, like most poets my age, I turned to Snyder—because few poets have managed to be so determined to tell the story of this earth. I had read and reread his translation of Cold Mountain by Han Shan, the hermitic Tang dynasty poet whose work is widely read but whose life is largely unknown. Both in a literal and in a figurative sense, I followed Snyder into the small presses and archives of American literature. His late friend and poet Carolyn Kizer was in Seattle, where Snyder read after the Six Gallery reading in San Francisco. It was October 1955 when Allen Ginsberg first read “Howl.” Kizer remembered how Snyder, at the reading in Seattle, after having read a few poems in traditional meter, announced, “Enough of this Yeatsean Eliotic stuff,” meaning, I can’t write words that hide from the reader. This was a crucial departure for Snyder—to recapture the audience for poetry would take years, but he would be central to making that happen. With the publication of Turtle Island in 1974, he pushed hard to return readers to the American landscape, to revere its presence in our lives, not just as an ornament but as a necessity. There was an acute awareness of its fragile state, and readers understood this urgency.

Snyder has long been associated with the ecological movement in this country because his preferences are for isolation over density, quiet over noise, personal over professional. He would, however, eschew such titles; I think he’d rather have a country without them, a country where each person has value, and the place they live in is equally valued. A narrative and often impressionist poet, he works back and forth between the lines to measure our presence in the unsettled world. Whether on the bow of a ship or in the twilight of a fire lookout, he is seeing what is often unseen, lying before starlight to ask simply: “It’s been years since I thought, / Why are we here?”

Snyder has friends in the Eastern Sierra Nevada and one of them is Robert Blesse, the former director of Black Rock Press. Blesse made a letterpress book, for a reading Snyder gave in the late 1990s, entitled Finding the Space. I remember, as it happened, being at the press when Blesse and Snyder were talking about the book. There was nothing triumphant about Snyder; he was just happy about having a letterpress printing his book. Later that night at a reception he was equally low key, as nonchalant as you might expect a person practiced in the natural world to be. He talked to me about Wendell Berry’s life as a Kentucky farmer because they are lifelong friends, two elder statesmen of the hard road, the road they held out to others so that this land we live on might not perish. Like Berry, Snyder has lived in a rural community for much of his life, made his living with his hands and his teaching. Snyder and Berry have functioned as counterpoints in this conversation, on opposite coasts of very different expectations. They have pulled and pushed to find a way to some sense of community that does not win, that does not echo defeat, that does not retreat from the quietness of species. They don’t always agree, but what two writers do? Their capacities for seeing the land and its stewardship as essential to our survival is what unites them.

Later, when I went back to my shelves, I found Snyder interviewed in the New York Times Book Review. When asked what the one book was that made him who he is today, he cited Ovid’s Metamorphoses. “I take it as a challenge,” he said, “to look for the storyteller of the planet.” In time Snyder will be looked upon as one of those storytellers of the past century. This LOA collection is at once an elegy to what we might yet claim as our present tense and a similarly foundational text for what we might do going forward. What he has left is a record of caring, of wanting this planet and its people to belong, not at the expense of the other, but as cohabiters of a physical world. This is the view that Snyder takes us to in almost every poetic outing: Consider what this world would look like if plants were revealed to be teachers, streams, the stories of our wetland beauty, sky and clouds, the memory of time before this. Snyder is a poet who has written from the depths of land and water. His odyssey of logger, shipmate, fire lookout, student of the East, and teacher in the West has given him a perspective of many decades, a way to belong to the globe without fear.