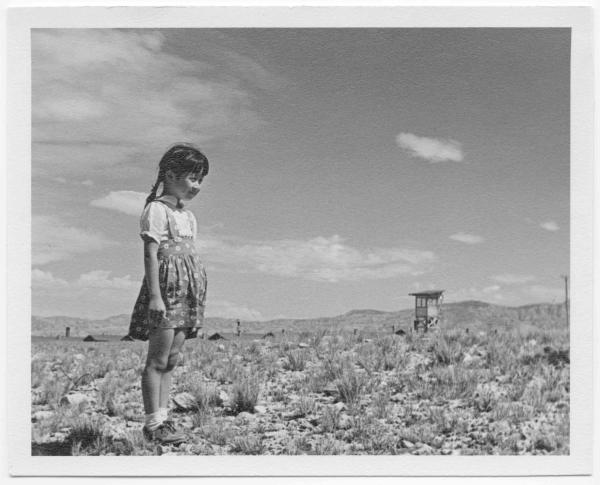

Between August 1942 and November 1945, Wyoming’s third largest community was the Heart Mountain War Relocation Center. In the arid sagebrush steppe of the Bighorn Basin between Cody and Powell and about 65 miles east of Yellowstone National Park, it had a high school football team that lost only one game in two years. Five-hundred-fifty-six babies were born in its 150-bed hospital complex. It had its own newspaper, the Heart Mountain Sentinel, Boy and Girl Scout troops, and flower arranging, needlework, painting, and thespian clubs. Hundreds of its residents were drafted or enlisted to fight in World War II, and two of these received the Medal of Honor. All of its approximately 10,000 residents were of Japanese descent, forcibly moved to Heart Mountain by the U.S. government after the December 7, 1941, bombing of Pearl Harbor by Japan and kept there by barbed wire and armed guards.

Heart Mountain, which took its name from the 8,123-foot-tall blocky mountain it sat in the shadow of, was one of ten internment camps that approximately 120,000 people of Japanese descent—about 80,000 of whom were American citizens by birth—were imprisoned in during World War II. After the war ended, these camps, in Wyoming, Idaho, Utah, California, Arizona, Colorado, and Arkansas, disappeared as quickly as they had been erected. Each prisoner received $25 and a train ticket to the destination of their choice. Camp buildings were sold off for as little as $1.

Today, several former camp sites are recognized as National Historic Sites and have museums and interpretive centers, including Minidoka in Jerome, Idaho, and Manzanar in Independence, California, both now part of the National Park Service. Heart Mountain was founded and run by the nonprofit Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation, established by former Heart Mountain prisoners working with local residents. NEH Jefferson Lecturer Sam Mihara has been on the board of the foundation since 2014.

“At . . . Heart Mountain, former incarcerees are the ones telling their stories,” says Aura Sunada Newlin, the executive director of the HMWF and a descendent of Heart Mountain prisoners. “It’s not filtered. This is our museum, and we are telling our stories in our voices.”

The stories the former Heart Mountain prisoners tell illuminate a part of American history left out of most textbooks and classrooms. Just 11 states require K–12 students to learn any Asian American Pacific Islander history. “I think the teacher of my A.P. U.S. History class mentioned once in one class that something happened to Japanese Americans during World War II,” says Ben Inouye, one of 72 teachers who spent a week at Heart Mountain last summer as part of NEH’s Landmarks of American History and Culture for K–12 Educators program. Inouye’s grandparents and great aunts and uncles were imprisoned at Heart Mountain. “I was stunned that this thing that was a personal story to me and so many other Japanese Americans and had so much to teach us was this throwaway comment in class.”

Heart Mountain sees itself as a reminder. Newlin says, “Democracy is fragile.

. . . We need to be reminded that when something scary happens we need to make sure we’re not reacting in ways that harm people on the basis of their status, race, or ethnicity.”

Today’s Heart Mountain complex includes the 11,000-square-foot Heart Mountain Interpretive Learning Center, which sits on the former site of the camp’s military police headquarters; a quarter-mile walking trail; a former prisoner barrack; three buildings from what was the camp’s 150-bed hospital complex; and the Mineta-Simpson Institute, a just-opened retreat space dedicated to helping leaders and groups from across the country work toward finding common ground across differences. The institute seeks to channel the lifetime friendship between Senator Alan K. Simpson and the late transportation secretary Norman Y. Mineta, who met through Boy Scouts at Heart Mountain—Mineta was a prisoner while Simpson lived in the nearby town of Cody.

Last summer, Wyoming Humanities supported a Heart Mountain digital storytelling project rooted in the fact that decades before Japanese Americans were forced to Heart Mountain, the U.S. government forced Native Americans off Heart Mountain. The project brought together Japanese American and Native American youth from the Apsáalooke tribe or Crow. The resulting 12-minute film about the three days they spent camping on the site and learning about each other will be screened around Wyoming this spring and on the HMWF YouTube channel later this year.

In the next year, the foundation hopes to have a portion of the only remaining football-field-sized root cellar stabilized so visitors can go inside. Heart Mountain prisoners finished the construction of a canal started years earlier by the Civilian Conservation Corps. This brought irrigation to about 1,800 acres of the camp and allowed prisoners to grow 45 crops, some of which had never successfully been farmed in the Bighorn Basin before because of its short (about 109 days) growing season.

In the museum, you can stand next to life-size cutout photos of several of the incarcerated farmers at Heart Mountain and read the wall text “What did we grow?” The use of photos and first-person testimony in exhibitions was possible because of the involvement of so many former prisoners. “It makes for a more powerful and empathetic visitor experience,” Newlin says. In the restored barrack, the HMWF is recreating the rooms of three former occupants; each space will depict barrack life from the perspective of that prisoner.

“One of the things that drives me is that the lessons of Heart Mountain are still really relevant,” Newlin says. “We’re not always at war, but there is almost always a sense of fear that is directed toward ‘the other.’ . . . Racism and failed political leadership are things we haven’t yet been able to conquer in our society. Heart Mountain wants to help.”