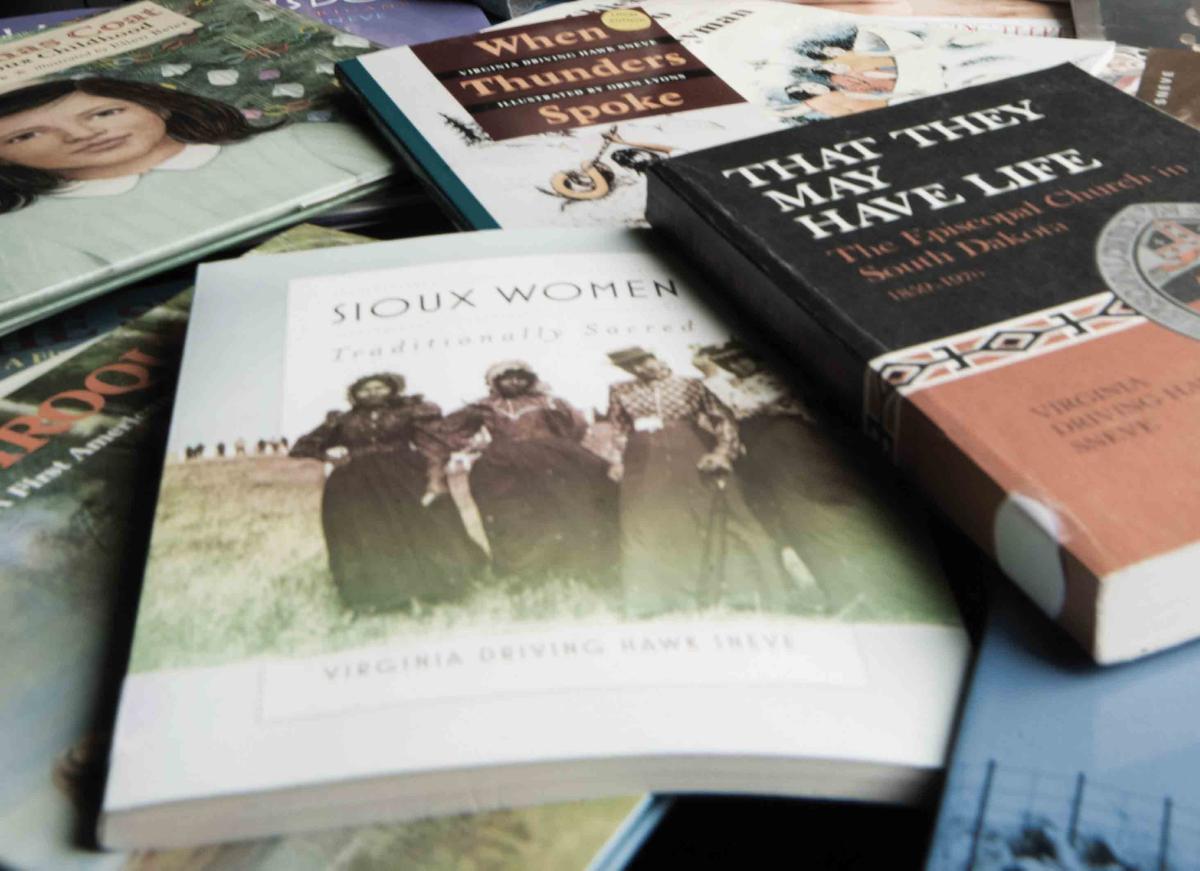

Virginia Driving Hawk Sneve is the author of 27 books. Her first book, Jimmy Yellow Hawk, published in 1972, is a charming children’s novel about life on the reservation and a boy who wishes people would stop calling him “Little Jimmy.” Many of Sneve’s stories come from her own life and family, such as in her memoir Completing the Circle (1995) and her story collection Grandpa Was a Cowboy and an Indian and Other Stories (2000). She has written a series of books for children about various Native American tribes: the Apache, the Cherokee, the Cheyenne, and several others. Among her most recent books are Sioux Women: Traditionally Sacred (2016) and The Christmas Coat: Memories of My Sioux Childhood (2019). She is ninety-one years old and the recipient of several honors, including, in 2000, the National Humanities Medal. NEH Chair Shelly C. Lowe (Navajo) interviewed Sneve in Sioux Falls this spring. Humanities magazine editor David Skinner sat in on the interview.

SHELLY C. LOWE: How did you get started as a writer and what kind of message were you trying to send to young people?

VIRGINIA DRIVING HAWK SNEVE: Well, there was an organization called Interracial Books for Children. It was a group of publishers and editors and writers and educators in the East. This was during the seventies in the wake of the Black power movement. People were very concerned that there was not correct literature for their particular group, Native Americans, Hispanics, Asians, or women. So they put out a call for manuscripts. I had been writing short stories, but I never had tried to get published. I submitted in the Native American category, and I got the award.

But what really had gotten me interested in writing for children was my daughter, Shirley. In school, she was reading Laura Ingalls Wilder’s stories of homesteading and pioneering on South Dakota prairies, not too far from where her father grew up, in Brookings, South Dakota. She asked him a lot of questions. Is that what it was like when your great-grandma came over here? Did they live like that? She was very curious about that.

I started reading the stories. The mentions of Native Americans were very scant. The stories talked about how this tribe would come through and they would walk right into the house without knocking. At first, Laura’s mother was very frightened. But the women became friends. And the Natives would bring them some venison or something like that. And then she’d give them something from her garden. So it was a positive relationship, but then Wilder talked about how frightening they were and dark and how they would burst into the house, and they looked very stern. And they smelled. They smelled like smoke. And they weren’t very clean. So that was the image that my daughter had of how Indians were.

Then I read the rest of the books and started seeing what she was reading in school and realized that there was a real lack of accurate information. Many of the stories for children had little boys and they would have an Indian friend whom they would help or save from something. Or there were nice Indian princess girls, that kind of thing, which is also inaccurate. Certainly, my daughter was not like that.

So that was kind of the spur for me to write in a way that showed we had a very important past and a lot of traditions and that we’re still here.

LOWE: As a teacher, what books did you have to work with?

SNEVE: I taught high school, American literature. We were reading stories about Native Americans written by non-Natives, so there would be inaccuracies. Like The Last of the Mohicans, the inference being that we had all perished and weren’t here anymore.

LOWE: What inspired you to start writing?

SNEVE: I grew up with grandmothers, fortunately. And my grandmother Driving Hawk, my father’s mother, was a storyteller in the traditional way. I have vivid memories of being with her during the summer. My parents would go off to pick potatoes or something like that. So we stayed with her. And it would be so hot in her little house, we would go sit outside around a campfire and throw sage on the fire to chase away the mosquitoes. And she would tell us stories. I have used that incident in some of my books.

So I began telling stories. My parents didn’t say I was lying. I was telling stories. And they encouraged me. I went to St. Mary’s School for Indian Girls. They recognized I had some ability. So they would encourage me to write my stories. That was the process, from the telling to the writing. And that’s how I got started.

LOWE: Were there any authors who really inspired you?

SNEVE: I read Charles Eastman. I knew his grandchildren. In my maternal grandmother’s family, there was a medical doctor, one of the first Native ones up in this part of the country. George Frazier was his name. He would write down the stories of his Frazier ancestors, who had to have come from Scotland after the Bonnie Prince Charlie fiasco, when they exiled the clan leaders to Canada. But I knew nothing about it at that stage of my life, how that had even happened or what it was all about.

LOWE: How was your work received?

SNEVE: It was all very positive. Native American teachers, especially, were just so gratified to have authentic stories written by an Indian person that they could use in schools. There were more sales in schools and libraries than to individuals at first.

I was criticized for using the word “Sioux” because that is not our name for ourselves. We call ourselves Lakota people. But there are other parts of the Sioux Nation who are Dakota. Some readers asked, “How come you’re always writing about Lakota and don’t say anything about the Dakota?” These were from Indian people. I wasn’t deliberately neglecting them. It’s just that I was writing about my people.

LOWE: And did you use the word “Sioux” because that was what was used at the time?

SNEVE: Oh, I have always had to explain that because non-Native readers would not understand that at all. Today people will say, “Dakota” or “Lakota” or “Nakota.” But, for a long time, it was just Sioux.

LOWE: What have you seen change over the years, particularly with representation of Native people and books?

SNEVE: Oh, it’s much more positive now and realistic. We have to accept there are some very tragic things that happened on both sides. Racism went—it still does—both ways. So I think it is necessary that we face up to and not gloss over the fact that some awful things did happen on both sides. I think people today are more aware and more accepting of that.

In South Dakota, you have to teach Native American studies at certain grades in elementary school and in high school. And now they will use literature that has been written by Native Americans. They’ve made a big point of that. So, my books are still used in schools, which is great.

LOWE: Who were your big champions in supporting the work that you have done?

SNEVE: My teacher, Mr. Miller, worked for the Bureau of Indian Affairs schools. He recognized that I had some ability, so encouraged me and gave me books from his own personal collection to read because the school library only had textbooks.

Then my parents sent me to St. Mary’s School. They did not want me to go to a federal boarding school because that’s where they went. The boarding schools banned the use of Native languages and imposed a military style of education. St. Mary’s was a small school, and it was really a prep school for girls. We were expected to go on for further education, whether it be college or nursing or something like that.

The students were taken to visit colleges: South Dakota State College and the University of South Dakota, because two of our administrators had graduated from those schools. I chose South Dakota State, which was not a fit because it is an engineering and science school. I had a difficult time, particularly with the math. It certainly was not a liberal arts college.

But there was an instructor there. Eva Nelson she was called. And everybody called her Big Eva because she was a big Scandinavian woman, almost stereotypically blond, Viking-type person, a wonderful teacher. She monitored what I was doing and was very helpful.

At the end of the first quarter, I went home, back to St. Mary’s, because my mother was working there. I brought everything I had. I was so homesick. I did not like school. I wasn’t going to go back.

So when it was time for me to go back, here come two of my uncles, my mother’s brothers. They literally threw me in the car and said, “You are going back to school, no doubt about it.” So I cried and hollered and swore at them all the way back.

My uncle Harvey said, “Now, you stay here. You’re going to be the first one in our family to graduate from college if you stay, and you are going to stay.” So I did.

Then I told Ms. Eva about that. And she said, well, good for them. And you are going to stay. I will help you.

LOWE: Did you come to like it?

SNEVE: Oh, yeah. I made friends. Mona Zephier from Pine Ridge and I were the only two Indians in the school at the time. She kind of took me under her wing. I think she was a junior at the time.

LOWE: Your dad was an Episcopalian minister? Is that correct?

SNEVE: Yes. He died very young, thirty-four years old. The church was very helpful in making sure we had a place to live. And they found a place for my mother at St. Mary’s as kind of a house mother for the girls. And she helped in the kitchen. There was a teachers’ college in Springfield. She went, and she got an associate of arts degree. Then she went to Sioux Falls where the diocesan office was. And she became the bishop’s secretary. That was a good move for her. While I was in college, she was living there. It was very helpful to have her that close.

LOWE: What was it like to grow up Lakota while being part of the church? Was there tension between the church and Lakota people who didn’t identify as Christian?

SNEVE: I didn’t sense that on the reservation. There was a rivalry, though, between the Roman Catholic Church and the Episcopal Church. On Christmas Eve, they would both have midnight services. And there was a race to be the one to ring the church bell first.

LOWE: Tell me what it was like to get the humanities medal. Did somebody call you?

SNEVE: I was stunned. I didn’t know what they were talking about. Vance, my husband, and I were in Spain. And I got this call, early in the morning from the front desk, saying that I had a long-distance call from the United States. And I thought of my kids, you know. Oh, dear. I hope everything is all right. And it was Bill Ferris of the National Endowment for the Humanities. He said, “You’re hard to track down.”

LOWE: I am impressed that he tracked you down in Spain at the hotel.

SNEVE: Norma Wilson, an instructor at South Dakota State University, was the one who had nominated me. So they called her. Then they called Shirley, my daughter. She gave them the phone number of the hotel.

But I didn’t know what he was talking about. I didn’t know what this organization was. He asked, “Are you going to be able to come to D.C.?” It was just before Christmas. And I said, “Oh, sure.”

Then, just shortly after I got home, I had a call from our local newspaper. NEH had sent out a press release. The newspaper people told me more of what it was and what an honor I was getting. I was just absolutely overwhelmed.

LOWE: Did Bill tell you it’s the president of the United States who awards the medal?

SNEVE: No, he didn’t. It was the newspaper people that said, “You’re going to get a medal from President Clinton.” And I said, “Oh, dear.”

Then to be there with all of these luminaries? I kept thinking, What am I doing here? I’m, you know, a little gal from a reservation. What am I doing here?

LOWE: I think that every day.

SNEVE: At the dinner, we were sitting at a round table. It was eight people, my husband and I, and people were passing out their business cards, asking, Do you know of any jobs in South Dakota in government or anything? This was because they had lost the election.

They had this big tent set up. And the Clintons walked around, saying hello. This was before the dinner. I met President Clinton and asked him if he would consider pardoning Leonard Peltier. He looked at me and said, “Well, you know, your governor”—that was Bill Janklow—“came to me and said that he had personally witnessed Peltier shooting the FBI agent,” at least one of them.

I looked at him and said, “I hate to say that my governor is a liar, but I don’t know how he could have been there.”

Then Clinton said, “I will pardon Peltier if he says he’s guilty.” But, of course, Peltier never has admitted to it, and he’s dying now, a sad thing.

LOWE: Was that your first time at the White House?

SNEVE: Yes. I was just absolutely amazed to meet Maya Angelou, Ernest Gaines, Barbra Streisand, Barbara Kingsolver, Yo-Yo Ma. Oh, and Eddie Arnold, the country- Western guy.

We used to go to this Scandinavian festival in Minot, North Dakota, every fall. They called it Norsk Høstfest, right? My husband was of Norwegian descent. And they had Eddie Arnold there the one time.

At the medals dinner he comes out on stage by himself and sings his songs. Afterwards, we went over and introduced ourselves and said we had seen him at Norsk Høstfest. He says, “That’s a good place for me to perform because I don’t swear, I don’t sing rowdy songs, and I’m laid-back and cool.” Well, he didn’t say, “cool.”

And the National Symphony played. Clinton directed them.

LOWE: Oh, wow.

SNEVE: After the dinner, we all went out back to the hotel. And we all sat around in the bar having drinks and getting acquainted.

LOWE: I was looking at Jimmy Yellow Hawk, your first book, and saw that it was illustrated by Oren Lyons. Is this the Oren Lyons that I’m thinking about? I didn’t know he was an illustrator. How did that come about?

SNEVE: My publisher, Holiday House, wanted to have a Native illustrator if they could find one. And they found him, I don’t know how. We never met. It was my first book. So I didn’t have the privilege of seeing the illustrations before publication. But I was pleased with them.

LOWE: I think he did a wonderful job.

SNEVE: It wasn’t until about my fourth children's book, The Chichi Hoohoo Bogeyman, that I was allowed to preview the illustrations. They had a picture of these girls on the cover. In the book, they’re in a canoe. The illustrator had them in a kayak. So I objected. After that, I got to approve the illustrations.

LOWE: You do a lot of interviews. Is there a question that you wish somebody would ask you that they have never asked you?

SNEVE: Most interviews that I’ve done are with non-Native people, professional journalists, who are totally unaware of what a reservation is and what kind of life that is. But they won’t ever know unless they go visit and spend some time there.

LOWE: I find that a lot of writing about Native people is focused on the problems, poverty, poor education, and so on. In my work and my colleagues’ work, we’re always trying to switch that so that we focus on the empowering things first. I think that a lot of your work has focused on the positive things.

SNEVE: That’s right. I try to do that.

LOWE: So what is your advice to young people? We’re really interested in trying to encourage young people to think about the power of the humanities.

SNEVE: Well, they should stay in school for one thing. We have such a high dropout rate for Native American students. They do well until about middle school. And as soon as they’re old enough, they’ll not return.

And read. I always say if you can read, a lot of things will fall your way because you can understand what is going on.

I taught at Oglala Lakota College in their English classes in extension in Rapid City. And I would get GED students who didn’t finish school but suddenly realized they needed more education to get a better job or something like that. Their skills would be pretty weak, especially in reading and writing. And so I would teach, well, children’s literature, for one, and use my stories and just to teach them how to read to their own children because if you don’t have a book in your home or a magazine or anything, just TV, they don’t read. And I said, you have to set an example that reading is fun and it’s just something you do for your own benefit, not just in school but at home, too.

LOWE: What would you like to tell our readers who are not coming to reservations and may not know quite as much about Native Americans?

SNEVE: I suppose it’s just to be open-minded about what they’re reading and hearing on TV and that sort of thing. They’re getting pretty much a one-sided point of view. To learn more, they need to make an effort to get beyond the usual stuff.

LOWE: What brings you joy? And how do you seek out joy?

SNEVE: Well, my husband died a year ago in January. And before that, he had dementia. So there was very little joy in our lives because it was a terrible thing to have to go through. But I really enjoy being around my grandkids when I can.

LOWE: With the history of tribal people in the United States, particularly some of the history that you presented in some of your books, how have you kept a positive attitude?

SNEVE: It has a lot to do with my father. I have told this story before, about how we were driving to the Black Hills from Rosebud. And it was during the war. So we couldn’t drive very fast, and he was worried about the tires holding up. We were going up into the hills. And I was so excited about that. We came to this little town with a gas station. That was Kadoka.

He was filling up the car with gas. I went around back to the outhouses. And there were three: a women’s, a men’s, and one for Indians. The women’s was locked. So I went into the Indian one. Then I went back to the car, and I told my folks. I said, “There were three toilets: one for women, one for men, and one for Indians.” I then said, “Wasn’t it nice they had a special place for Indians?”

I remember my parents looking at each other. And my dad said, “I hope there will always be a special place for you.”

LOWE: I do like that. We have our own.

SNEVE: Yeah, our own toilet. Now, my father always worked on the reservation. And I’m sure there were a lot of problems and difficulties, but he never seemed to get depressed by it at all. And it didn’t affect us. My brother was kind of the same way, very cheerful attitude about things.

LOWE: Was there anything you always wanted to write about that you didn’t get to write?

SNEVE: I’m working on a novel that I have been working on, off and on, for years, and I just might finish it.

LOWE: Do you want to give us any teasers about it, what it is?

SNEVE: Well, it’s actually based on my grandmothers as they were growing up on the reservation and the things they experienced.

LOWE: Exciting.

SNEVE: Well, I don’t know if it will be exciting, maybe informative. I’ll have to see.

LOWE: You were saying a lot of students don’t know who you are and don’t know your work. I’ve heard that sentiment about Vine Deloria’s work, too.

SNEVE: Really?

LOWE: Yeah, that young people now, especially Native people who enter college, have never heard of Vine. That’s kind of scary, I think.

SNEVE: Yes, it is.

LOWE: It tells us we’ve got some work to do.

SNEVE: Vine and I knew each other as children because both of our fathers were Episcopal priests. My mother told the story about going down into the basement to check on us. And I was standing there, screaming. Vine had my finger in his mouth. I still have a scar. He bit my finger. And it was bleeding. So every time I saw him, I held my finger up.

We used to go to Camp Remington in the Black Hills. The clergy would build their own cabins there, sort of a church camp kind of a thing. And we stayed there one summer with the St. Mary’s group, me and Vine and a couple of other kids whose parents were clergy and were off someplace. For a couple of weeks, we would be there. They just turned us loose in the hills. We hiked all over in the mountains and then didn’t get lost, just absolutely a fun time.

LOWE: Best way to grow up. Did any of Vine’s work influence you?

SNEVE: Oh, I read his work, and, of course, remember him as a teenager. I didn’t think that he would be such an influencer and an activist. I was impressed.

LOWE: Is there anything you have, David, that you would like to make sure we talk about?

DAVID SKINNER: I want to ask about your novel Betrayed, which is about the 1862 Sioux Uprising. I was struck by how sympathetic you were about both sides of the conflict. How did you work your way mentally into the space of the settlers and the Santee?

SNEVE: Well, I’m biracial and have family who were among the Native Americans exiled from Minnesota, and I knew how they were treated. But I also knew white people whose ancestors had experienced the same events and the difficulties that they went through. I think the fact that I am a biracial person has influenced my writing. There are two sides and I’m sympathetic to both and try to express that as accurately as I can.

SKINNER: There’s also a beautiful passage in Grandpa Was a Cowboy and an Indian, where Grandpa describes a fight at a ranch where he’s working. It’s a fight between an Indian man and a white man. And everyone takes sides, except for him. He’s not sure what to do. Then he gets punched by a white man. So he punches back. And then he gets punched by an Indian. So he punches the Indian. And he ends up rather confused about whose side he was on. Do you feel some perplexity like that?

SNEVE: Oh, yes. Many of us who are mixed bloods have had this quandary over the years. Indians will accuse us of trying to be white, that kind of thing, and the other way around. So yeah. It’s been a mixed blessing.

SKINNER: Do you think of yourself mainly as a writer translating an oral tradition?

SNEVE: I’m a storyteller.

SKINNER: It’s all storytelling?

SNEVE: Yep.

SKINNER: Are there writers today who you admire?

SNEVE: Agatha Christie. I’ve always been an Agatha Christie fan. And I read Stephen King. He is a good writer. I like the way his descriptive passages soar. It has you feeling it immediately. So it’s a good tutorial in a way, his work.

SKINNER: Do any contemporary Native American writers mean anything particular to you?

SNEVE: N. Scott Momaday. We were at a writers’ conference one time. And I was just so awed by his poetry. I felt I’d never ever be able to use words like that. His use is so great.

LOWE: I feel like there was this era of the Native writers that came out: Scott Momaday, you, Joy Harjo, Leslie Marmon Silko.

SNEVE: Just in that one period, yeah.

LOWE: What was it like at that time?

SNEVE: Very thrilling. Especially when we’d get together at a writers’ conference or in a group to exchange ideas. It was just wonderful to know there were others out there doing this at the same time.

I was probably the only one who was writing for children particularly. I never felt like I couldn’t write for adults. But the simplicity of my language makes it a little easier to comprehend, even for an adult.

LOWE: When you were publishing your books, did you travel all over?

SNEVE: I used to travel, especially to schools. I enjoyed that. I used to receive drawings from students. There would be a class project for them to illustrate the stories and how they saw it. And often they would want a different ending. So they would rewrite the ending.

LOWE: That’s a good way to get them to write. All of your papers went to South Dakota State? Is that right?

SNEVE: Their archives, yes. They’ve been used for research and different things, especially writing for Native American children.

Actually, South Dakota State was doing a workshop on poetry and playwriting. Now I’ve written poetry over the years but never had any interest in playwriting. I said I think I’d like to go to that. So I applied, and they turned me down. They said, We’re sorry. We know that you would probably like to take this, but you would intimidate everybody.

And I said, What? I never thought that being an established, published writer would make me intimidating. So I didn’t get to take that. And I still haven’t written a play.

LOWE: Well, you can write one after you finish your novel.

SNEVE: Okay.

LOWE: Thank you for the interview.

SNEVE: You are welcome.