When Joe Papp was in junior high school in Brooklyn during the Depression, his teacher read a scene from Julius Caesar.

“It was a speech about rousing people to action and loyalty. I loved that speech,” he said. “You blocks, you stones, you worse than senseless things. Oh, you hard hearts, You cruel men of Rome. I identified with the character. He was protesting some injustice done to someone he cared for. I didn’t understand a lot of the things but it sounded so good. And I memorized it. I didn’t admit to anybody that I loved Shakespeare. On my block, if you told that to any of those guys, they’d beat you up.”

With a simple yet radical idea that Shakespeare, the greatest writer in the English language, was not the property of the educated, or the middle class, or the upper class, but everybody, Papp took Shakespeare to the people of New York, free of charge. In doing so, he created a cultural phenomenon, Shakespeare in the Park, that has become a summertime staple throughout the country in countless towns large and small, and throughout the world.

Through the New York Shakespeare Festival, he was among the first to give minority actors major Shakespearean and other classic roles. And through The Public Theater, Papp championed the work of contemporary and experimental dramas and musicals including Hair (1967), Sticks and Bones (1971), That Championship Season (1972), A Chorus Line (1975), and for colored girls who have considered suicide / when the rainbow is enuf (1976).

“When I was growing up, Joe Papp was this larger-than-life figure,” says Tracie Holder. “He was on the front lines of every social issue that I held dear. . . . He turned down $323,000 [from the National Endowment for the Arts], money he desperately needed, rather than give in to this form of censorship. There wasn’t anybody else fighting the good fight and standing up for principles, speaking truth to power the way Papp was. . . . I never fully understood why he was in theater. . . . and then I saw Threepenny Opera. I realized the power of art to engage people around ideas and around issues in a way that’s more impactful than politics.”

“He believed great art was for everyone and he could engage what he called ‘the culturally dispossessed’ through theater,” says Karen Thorsen. “He’d argue that we have public libraries, why not public theaters?”

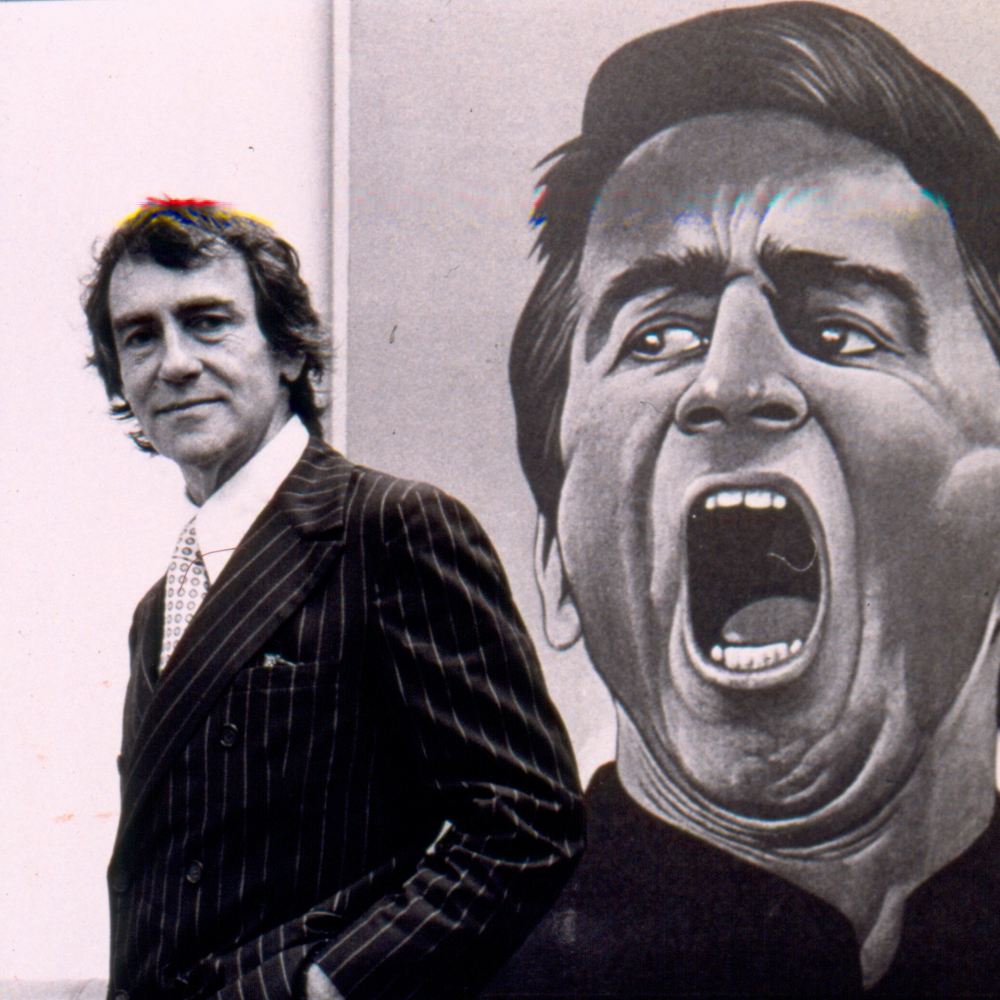

Papp’s rise from the rough-and-tumble Brooklyn streets to free Shakespeare in a church basement to the largest nonprofit theater in America is told in Joe Papp in Five Acts, a new American Masters documentary airing on PBS on June 3, directed and produced by Holder and Thorsen. Because Papp left a vast archive of festival documents, memorabilia, video and audio tapes of productions, television interviews, and reminiscences from the 1950s until his death in 1991, Holder and Thorsen had a treasure trove of material to let Papp and others tell his story without added narration.

“At the height of his success with A Chorus Line, where he’s flush with cash, he thought that one theater in America should have a documented history. And, of course, that should be his theater,” says Holder. “So, Papp hired four full-time archivists. When he died, he left behind the single largest archive the New York Public Library ever received.” Holder and Thorsen also filmed actors, directors, and playwrights who Papp helped launch, including James Earl Jones, Martin Sheen, Meryl Streep, Roscoe Lee Browne, Mandy Patinkin, Christopher Walken, George C. Wolfe, David Rabe, David Hare, Ntozake Shange, Liz Swados, and many others.

“He was a complicated guy, he was difficult, he was autocratic,” says Holder. “But they really knew who he was. Nobody placed him on a pedestal. They . . . described him as flesh and blood, and yet, they loved him. To me, that is the highest tribute you could pay to somebody is to really see them for who they are and still love them despite their flaws, and to recognize what they had achieved.”

After high school, with no money for college, Papp joined the Navy during World War II. He was stationed on an aircraft carrier, where he put on vaudeville sketches for the sailors (including shipmate Bob Fosse). After the war, he studied acting and directing at the Actors’ Lab in Los Angeles on the GI Bill, becoming its managing director. It was there he was exposed to theater, for the first time, theater about things he cared about. “This theater embodies social activism. It’s this democratic vision of art and a place to engage people around ideas,” says Holder. It was also there that the L.A. Bureau of the FBI began to track his activities.

After the Actors’ Lab closed in 1948, Papp toured with Death of a Salesman, which landed him back in New York, where he worked a series of odd jobs until he eventually was hired as a stage manager at CBS in 1952.

“After the Actors’ Lab, I was always trying to start a theater,” said Papp. “I was consumed by the idea.” During his time at CBS, according to biographer Helen Epstein, he read and reread Shakespeare, slipping in and out of Shakespeare like others do Yiddish or Spanish, comparing coworkers to Shakespearean characters, “and salting his speech with Shakespearean lines the way observant Jews quoted the Bible.”

While still working at CBS, with borrowed equipment and no small amount of hard work, Papp started staging free outdoor Shakespeare in 1956 at the East River Park Amphitheater on Manhattan’s Lower East Side, one of the roughest neighborhoods in the city. Thorsen says, “He found this abandoned concrete stadium bandshell, and puts on The Taming on the Shrew with an unknown Colleen Dewhurst, which gets positively reviewed in the New York Times even though it gets rained out after the first act.”

Dewhurst recalls her first encounter with Papp: “I got a call one day and this voice came on and . . . said, ‘My name is Joe Papp. . . . I’m going to start a company. Shakespeare for the people. Something that is free.’”

“The first show that opened here, with no advertising, nothing, just opened the doors and the place was packed,” said Papp. “Old people, young people, Jewish people, Hispanic people, Black people. Hundreds of people.”

“They laughed, they roared. The people would yell. They’d go, look out! Here she comes, look out!” says Dewhurst.

“He embodies the essence of democracy,” says Holder. “He really wants everyone to feel welcome on both sides of the footlights. His vision is about having a forum that is truly democratic where everyone can be heard and everyone can be seen, and everyone can participate. When he starts his own theater, his goal is not to go to Broadway, it’s to bring theater to people who had never seen theater. It’s bringing the mountain to Muhammad.”

The Times review was a turning point for Papp, providing more press, more backers, more leverage.

In 1957, Papp created a mobile theater that traveled to neighborhood parks, ball fields, and playgrounds in all five boroughs. “It was so characteristic of Joe to think that what was good in the borough of Manhattan would be even better were it to be extended to the outlying boroughs,” says Bernard Gersten, Papp’s friend and the associate producer of the New York Shakespeare Festival.

Myles Reilly was eight years old when the theater rolled into Harlem.

“I look outside the window and something is going on in our park. A couple of trailers show up. They start building something. I don’t know what the hell it is.”

It was a thirty-five-foot trailer pulled by a retrofitted sanitation truck. The stage would unfold, and, like magic, the park transformed into a theater, complete with a stage, dressing rooms, lighting, and seating for more than two thousand people.

“I’m sitting there in these bleachers and all of a sudden there’s these people in the weirdest garments I’d ever seen in my life,” says Reilly. “My father’s sitting next to me and we’re just watching, you know, Shakespeare.” Reilly went on to work at The Public Theater.

“People were dealing with Shakespeare for the first time, probably theater for the first time,” says actor James Earl Jones, an early and frequent collaborator with Papp.

A Times review in 1964 of a mobile performance of A Midsummer Night’s Dream said, “Civil rights and other weighty problems receded into the darkness for a few hours in Harlem last night as Shakespeare’s wit and humor took over and captivated an audience. . . . An old woman, who refused to identify herself, said that she had been a resident of the community for 26 years. ‘This is the first time that people have cared to come in here,’ she declared. She asked for handbills to distribute to her friends and neighbors, and wanted one to put in her window.”

Papp was one of the first to cast Black and Hispanic actors in major classical roles. “Joe wanted to fill the stage with the same kind of people he was going to fill the audience with, all the people of the city,” says Jones. “He tried everything to open up the whole issue that you’re casting human beings. He would cast Hamlet as a woman.”

He encouraged Martin Sheen and Raul Julia to perform Shakespeare with an authentic Hispanic accent. Sheen says, “Joe asked me to try the ‘To be or not to be’ out of my heritage. My father was Spanish. My real name is Ramón Estevez. He hid Hamlet in the play as a kind of Puerto Rican janitor. The Puerto Rican community were at the bottom rung at this time, and he wanted people to feel their plight.”

Sheen recalls, “The audience was in hysterics when it started, until about halfway through, and they began to listen, some of them for the first time. And by the end, many of them were in tears. So, we were using this language that was nearly 400 years old at the time, in a community where people were suffering and this language was given a new voice.”

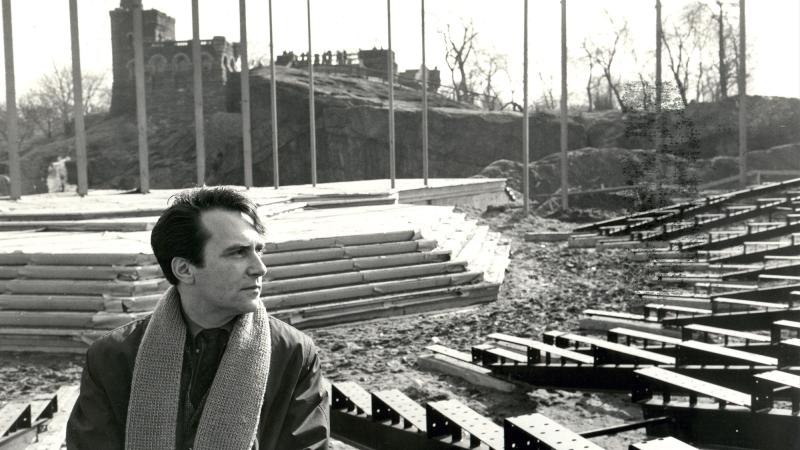

In the summer of 1957, after putting on shows throughout the city, the mobile theater was headed for Central Park. By the time it got near Belvedere Castle in the park, the truck would no longer roll. Papp left the truck there on a patch of civic grass, claimed squatter’s rights, and staged Romeo and Juliet, Two Gentlemen of Verona, and Macbeth on a temporary stage. A beloved New York tradition was born—free Shakespeare in the Park—drawing thousands for every performance, then and now.

In 1958, Papp was called to testify before the HUAC about his political activities. When asked to name names, Papp invoked the Fifth Amendment. That evening, he was fired from CBS and fought to get his job restored, which he did. But he never returned to CBS and instead devoted his time to theater.

After two successful seasons of free Shakespeare in Central Park, Robert Moses, the most powerful politician in New York at the time, claimed that theatergoers trampled the grass and Papp needed to charge admission to pay for the replanting. No stranger to a good fight, Papp wouldn’t knuckle under.

“There was something I think, too, that he loved about the struggle, loved about the scrabbling,” says actor Meryl Streep. “It didn’t mean much if it all came easy. It didn’t mean much if there wasn't a fight involved.”

“He was kind of an art Rocky,” says Lee Breuer, who directed Shakespeare in the Park’s The Tempest, starring Raul Julia. “You wanted to cheer when he got up and went and screamed for money or when he fought Robert Moses.”

“I thought it was absolutely essential that in order to attract an audience that represented all groups, regardless of their ability to pay, and even those that could pay, to get them into the theater, to give them an experience with a living play and Shakespeare,” said Papp. “I felt even a quarter would be too much. I feel there are public libraries that are free. I felt a city the size of New York should have a public theater.”

Moses played dirty and leaked to the press that Papp was a communist. Papp fought back in the press, suggesting his free plays didn’t damage the park any more than football or any other sport. People took sides, even Eleanor Roosevelt: “It seems strange to me that Mr. Robert Moses, New York City Parks Commissioner, who once was enthusiastic about such things, should now want to ban the Shakespeare Festival from the city’s Central Park. The real value that comes to our city through the production of Shakespeare and the fact that the performances would be open to all is so great that I cannot help wishing that his decision might be changed. We must realize that the city pays for health and education and gives its citizens other things in return for their taxes, and this seems to be one of the legitimate expenses for education.”

In retaliation, New Yorkers sent envelopes of grass seed to Moses.

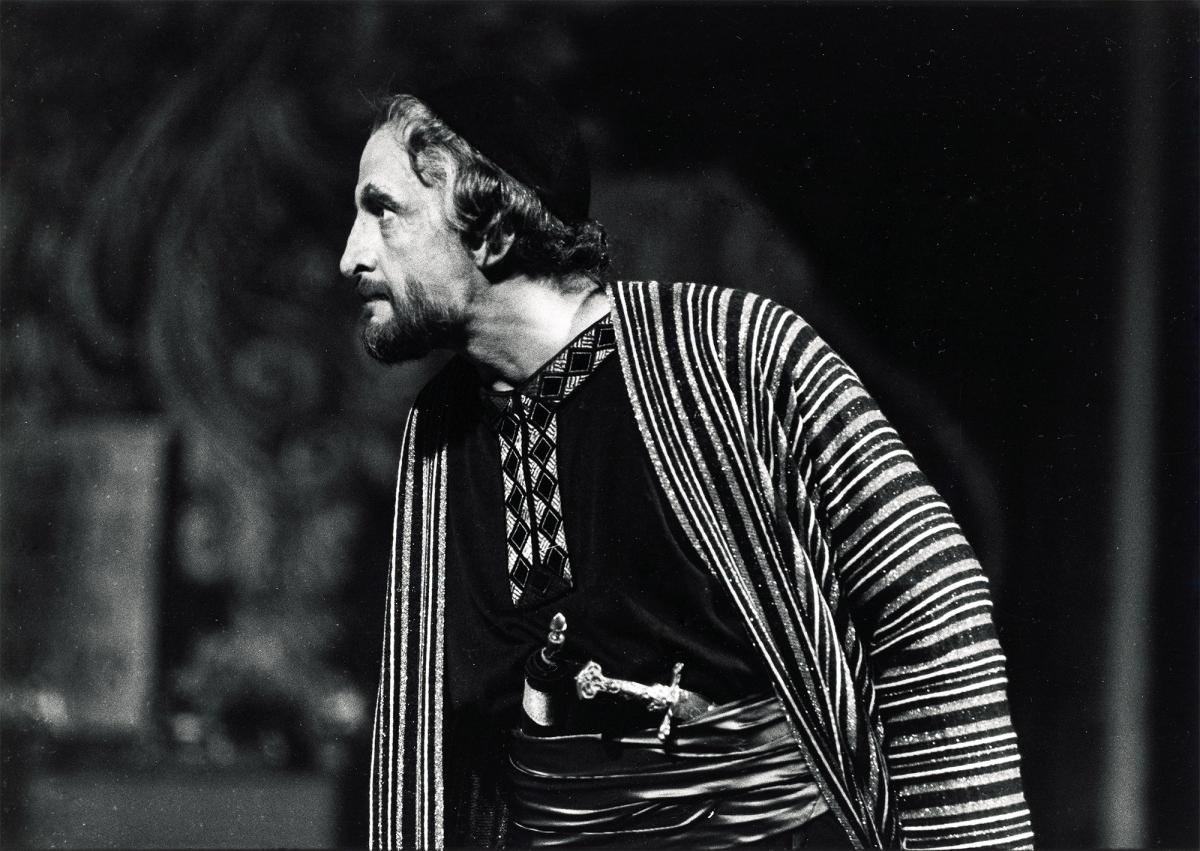

Papp won in the court of public opinion and the court of appeals. The season went on, free of charge. Through sheer grit, Papp’s New York Shakespeare Festival had become a major metropolitan institution. A few months later, Moses did a turnaround and requested $250,000 to build a permanent Shakespeare-style amphitheater in Central Park. The open-air Delacorte Theater was built on the same site near Belvedere Castle. It opened in 1962 with The Merchant of Venice, starring James Earl Jones and George C. Scott as Shylock.

But then, as Jones says, “The shit hit the fan.”

The New York Board of Rabbis believed the play was anti-Semitic.

Papp was perplexed. “I never thought of the play as being anti-Semitic. It never entered my mind. I just considered this an important play of Shakespeare’s and had a marvelous actor to play this role which I thought was one of the great acting roles. And I was totally unaware that there’d even be an objection to this play.”

Then Papp dropped a bombshell.

Gersten recalls, “To our amazement Joe said, ‘I myself am a Jew.’ You must understand, nobody knew that Joe was Jewish. We were best friends and very, very thick and very close and I didn’t know. Joe had escaped his past for nearly thirty years.”

Papp was born Yussel Papirofsky in 1921 to Shmuel and Yetta Papirofsky. Yiddish was his first language. Papp said, “The whole idea of being part of a minority and not being able to speak the language, and your parents don’t speak English. I was embarrassed, ashamed to invite anybody to my house. I remember being invited to somebody’s house and the mother spoke English. She said, ‘Come in. How are you?’ That sort of thing. I knew my mother couldn’t say that.”

After seeing his father denied work, he concealed that he was Jewish, telling his second and third wives that his mother was British.

“The Merchant of Venice did go on,” says Gersten. “And the humanity of George as Shylock was profound. But the most important consequence of all this was that Joe finally admitted that he was Jewish.”

“The irony about Papp is that while he’s denying his own identity, he’s welcoming everyone else in,” says Holder.

Around 1965, Papp started looking for a year-round theater where he could stage Shakespeare and expand his mission to offer a home where American playwrights could create their own classics.

In 1967, he moved into the dilapidated former Astor Library on Lafayette Street, the first free public library in New York that had been converted into a shelter for homeless Jews after World War II. Mandy Patinkin says, “For thousands and thousands of Jewish immigrants, this was their first home, including my grandpa Max. You can still see the letters on the side of the building, HIAS, the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society.”

After a massive renovation, Papp opened the New York Shakespeare Public Theater with the tribal rock musical Hair to very mixed reviews. Producer Michael Butler wanted to take the show to Broadway and add nudity, which Papp didn’t think would work. He sold the show to Butler for a song, and it became an instant hit.

“He never made that mistake again,” says Holder. When A Chorus Line transferred to Broadway some years later, he retained a big percentage of the rights, which helped finance many years of experimental productions.

At The Public Theater, Papp continued to support plays that dealt with social issues, working to help artists and plays succeed in finding new audiences. In 1985, he staged Larry Kramer’s The Normal Heart, the first major play to address the AIDS crisis.

In 1987, Papp announced a six-year program to present all of Shakespeare’s plays. That same year, he was diagnosed with prostate cancer, and his son Tony was diagnosed with HIV. In 1991, Tony died on June 1 and Joe on October 31. The lights on Broadway dimmed in his honor.

The Public Theater continues Papp’s vision for a more just society through theater. Recent groundbreaking shows include Fun Home and Hamilton. In 2013, the Mobile Unit was reborn, presenting free Shakespeare to prisons, homeless shelters, and community centers throughout New York’s boroughs.

For Papp, “The only practical means of ensuring the permanence of our theater is to tie it in with civic responsibility. The public library, an institution for enlightenment and entertainment, is a case in point. I know that if I had to pay for books at the Williamsburg Public Library, it is doubtful that I would have read the plays of Shakespeare.”