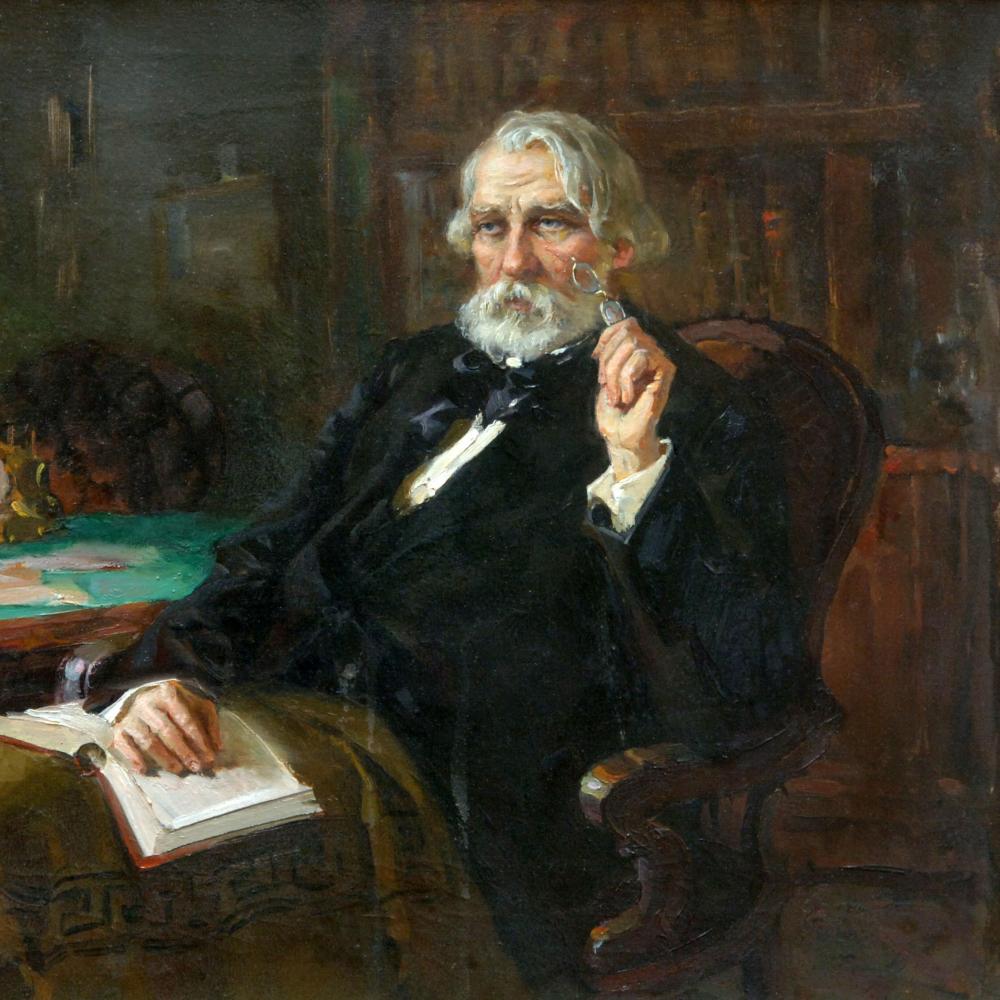

Ivan Turgenev is not as popular as he once was—at least not in the West. Gustave Flaubert considered him “a master.” “The more I study you, the more your skill leaves me gaping,” he wrote the slightly older novelist in 1863. William Dean Howells wrote in 1895 that life “showed itself to me in different colors” after reading Turgenev. “Who else but Turgenev,” Howells continued, “ever felt all the rich, sad meaning of the night air drawing in at the open window, of the fires burning in the darkness on the distant fields?”

The Russian left and right both distrusted him after the publication of Fathers and Sons (1862). The former felt the novel was too critical of young revolutionaries, and the latter that it was not critical enough. But the novel made him briefly the dean of Russian literature in the eyes of the West—until, that is, the publication of Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment (1866) and Tolstoy’s War and Peace (1867).

Twentieth-century critics and novelists, following Henry James, have mostly viewed him as a master of portraiture and an exquisite stylist but lacking in intellectual heft. James preferred Turgenev to both Dostoevsky and Tolstoy, but in praising the novelist for his delicacy and nuance at the expense of his ideas, he made him out to be merely an aesthete. James held that Turgenev’s portraits of Russian serfs in his first book, Sketches from a Hunter’s Album, for example, were superior to Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin precisely because Turgenev makes his case through the “cumulative testimony of a multitude of fine touches.”

There’s an echo of James’s “fine touches” in Vladimir Nabokov’s remark that Turgenev was “not a great writer but a pleasant one.” A few years ago, A. N. Wilson, following Nabokov, wrote that Turgenev may have been the author of a few “perfectly pleasant books,” but he lacks the power of either Dostoevsky or Tolstoy. Even Fathers and Sons, Wilson argued, was a failure. It is composed of “a nicely drawn set of scenes . . . the characters are realistic. The furniture, the clothes, and the food are all accurately described. . . . We see freshly picked bunches of lilac arranged near the samovar. . . . You can see it all. But there is a complete emptiness in this Russian Literature-Lite which leaves the reader hungry.”

Wilson is right that Fathers and Sons doesn’t equal Dostoevsky’s best books (though it’s better than The Brothers Karamazov in my view) or Tolstoy’s epics, but his claim that it is merely “nice” is as silly as it is dated.

In his 1970 lecture on “Fathers and Children: Turgenev and the Liberal Predicament,” Isaiah Berlin remarked that Turgenev was “often described as a pure aesthete and a believer in art for art’s sake, and was accused of escapism and lack of civic sense. . . . Yet these descriptions do not fit him.” Berlin goes on to explore Turgenev’s subtle critique of materialism and nihilism through the character of Bazarov in the novel. The portrait was so on-the-nose that one of Turgenev’s liberal friends, Berlin writes, told him to burn the manuscript “since it would compromise him forever with the progressives,” which it did. Turgenev, of course, refused—no doubt nicely.

One of Turgenev’s big ideas—in both Home of the Gentry and Fathers and Sons—is that life is mostly one of loss, though not irrevocably so. The question is what might be salvaged and how. Decisions we make in our youth—often on a whim with little understanding of ourselves and the world—can change the course of our lives. The tragic outcome of those decisions is only fully felt when it is too late. In other cases, the world changes without us, leaving us strangers in our own homes, and there is very little we can do about it. Life is unfair, and it is the lot of adults, Turgenev argues, to respond to this state of affairs with humility and composure.

In Gentry, for example, we follow the life of Fyodor Lavretsky, a wealthy landowner, who falls in love with a beautiful woman named Varvara Pavlovna after he sees her at an opera in Moscow. Six months later, the two are married. They move to Paris, where Pavlovna becomes a popular salon hostess of artists and journalists. After some time, Lavretsky discovers she has been having an affair with a young Frenchman. Rather than divorce her or seek an annulment, he gives her an annual income and sends her away. After traveling to Italy, Lavretsky returns to Russia, where he falls in love with a young but virtuous woman named Liza. She, too, has feelings for him, and it looks as if a marriage may be possible after Lavretsky learns that his wife has died.

Their hopes are dashed, however, when Varvara Pavlovna unexpectedly shows up at Lavretsky’s house with a daughter in tow and informs him of her decision to take up residence at the family estate. Liza joins a convent and Fyodor Lavretsky lives out his days alone with only his memories of his time with Liza to sustain him. While Lavrestky could have given into “a kind of cheap universal skepticism,” like one of the other characters in the novel, he accepts his fate, recognizing the role he played in determining it, however unfair it might seem, without lashing out childishly.

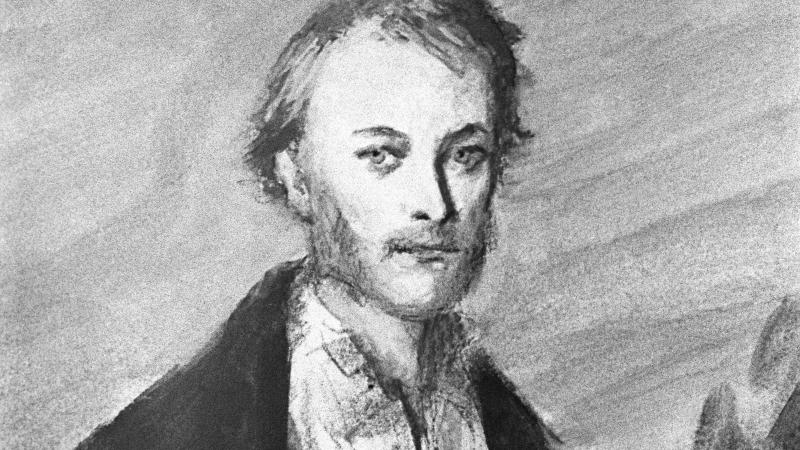

Fathers and Sons is equally wise. The novel opens with Nikolai Petrovich Kirsanov waiting at the train station for his son, Arkady, to return from the university for the summer. Arkady arrives with a friend, a nihilist named Bazarov, who knows everything and scoffs at everyone who disagrees with him (particularly at Nikolai’s brother, Pavel Petrovich, for his outdated ways). Arkady, like a puppy, loves everything Bazarov says and does.

Bazarov and Pavel argue incessantly. Bazarov has espoused all the new thinking; Pavel is a man of the past. He never married and hangs on to his aristocratic ideals because it is the only thing he has left. But that world is quickly passing away, and, as Turgenev writes, “in losing his past, he lost everything.”

In the middle of the novel, after a particularly heated argument, Pavel complains bitterly: “So that! . . . so that’s what our young men of this generation are! They are like that—our successors!” This leads Nikolai to a hard conclusion that he nevertheless accepts:

“Our successors!” repeated Nikolai Petrovich, with a dejected smile. He had been sitting on thorns, all through the argument, and had done nothing but glance stealthily, with a sore heart, at Arkady. “Do you know what I was reminded of, brother? I once had a dispute with our poor mother; she stormed, and wouldn’t listen to me. At last I said to her, ‘Of course, you can’t understand me; we belong,’ I said, ‘to two different generations.’ She was dreadfully offended, while I thought, ‘There’s no help for it. It’s a bitter pill, but she has to swallow it.’ You see, now, our turn has come, and our successors can say to us, ‘You are not of our generation; swallow your pill.’”

It may seem that Nikolai is giving up too easily, but there’s wisdom in his resignation, and it’s this: The younger generation will replace you whether you like it or not and espouse ideas you find foolish or horrendous, and one day there will be nothing you can do about it. Yes, young people can be brash and stupidly self-confident (so self-confident, in fact, so afraid of appearing not to know something, that they don’t realize how obvious the charade is). One day, they too will be replaced.

This doesn’t mean that the older generation should simply give up. Not at all. Nikolai doesn’t, but his discourse is seasoned with the salt of humility. He knows he’s limited and finds consolation in the fact that other people are limited, too.

If you’ve read the novel, you know that it turns out happily for both Nikolai and Arkady. Life may be one of loss, but it’s also one of occasionally delightful surprises. Still, those surprises are rarely brought about by the great action of a great man. They simply happen.

Turgenev has probably never been more out of style than he is now. He is a stoic at a time of activism, a realist at a time of fanaticism, and a moderate at a time of extremism.

His novels remind us, however, that life does not owe us anything, no matter how many demands we make of it (or “rights” we assert), and that there is a nobility in being prepared to suffer because of the actions of others—knowing that you, too, have harmed others in ways in which you are not aware. He was against radicalism of all sorts, believing that it turned men against each other, which leads to all sorts of evil.

Home of the Gentry and Fathers and Sons are deeply humane novels precisely because they remind us that people are people—never gods and rarely beasts—limited and flawed, yes, but capable of quiet acts of love and sacrifice nonetheless.