The Negro leagues once sat at the center of Black communities across America. Yet today, more than a hundred years after their inception, remnants of only six surviving Negro league facilities still exist: Rickwood Field (Birmingham Black Barons), League Park (Cleveland Spiders), Hinchliffe Stadium (New York Black Yankees and New York Cubans, a Latino team that played in the Negro leagues), J. P. Small Memorial Stadium (Jacksonville Red Caps), Cooper Stadium (Columbus Blue Birds), and Hamtramck Stadium (home to many teams, including Detroit Stars and Wolves). These spaces are reminders of a time when fans, dressed in their Sunday best, filled baseball stadiums to witness the impressive show of Black sporting talent and production. They represent the Negro leagues’ remarkable legacy and the communities they cultivated.

Black baseball became one of the more profitable businesses in some Black communities. It made a considerable contribution to an enclave economy composed of interrelated businesses that succeeded in response to forced segregation. The Black Kansas City Monarchs team “would have people go around to the local businesses and ask them to close so that more people would attend games. It was really a big deal, and sometimes people have no idea of how important these games were to the economics of not just baseball but to the community as a whole,” explains Phil Dixon, a presenter for the Kansas Humanities Council’s Speakers Bureau.

Phil Dixon is an award-winning historian who has spent decades weaving Black baseball into the larger American baseball tapestry. He is a cofounder of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City, Missouri, and his work has covered Black baseball since its inception following the Civil War. His books reveal the way shared experiences and the racist treatment of Black people forced players, coaches, management, businesses, and fans to support each other. According to Dixon, if it wasn’t for the support of promotors and cities that allowed Black teams to play, many teams would not have made money or been able to operate.

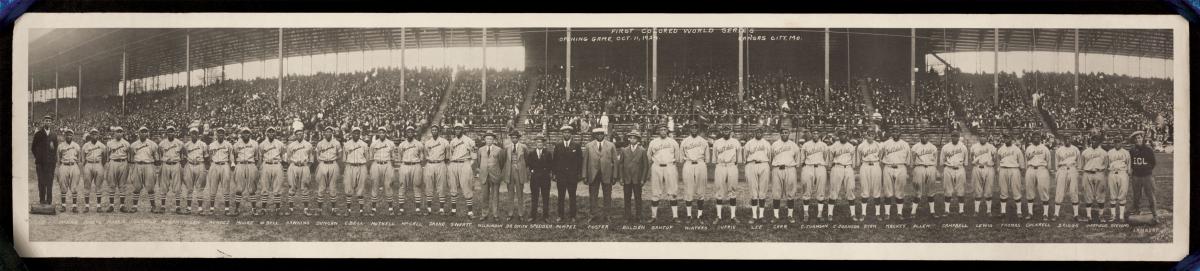

Baseball’s color line was drawn in the dirt in 1867, with a “gentlemen’s agreement” among white owners and managers to restrict their leagues to white players. To play, Black athletes resorted to barnstorming, which was often undermined because of bad booking agents and unstable teams. But on February 13, 1920, at Kansas City’s Paseo YMCA, the fate of Black baseball changed. In his book, Andrew “Rube” Foster, a Harvest on Freedom’s Fields, Dixon recounts how the owners of eight of the top clubs gathered at the invitation of Foster and Charles Isham “C. I.” Taylor to create the first sustainable Black league, the Negro National League (NNL). Foster was elected president of the NNL, and Kansas City Monarchs owner James Leslie “J. L.” Wilkinson (who was white) was elected secretary. Players such as Larry Doby, James “Cool Papa” Bell, Satchel Paige, Josh Gibson, Buck Leonard, Monte Irvin, Othello “Chico” Renfroe, Verdell “Lefty“ Mathis, Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe, Oscar Charleston, William “Judy“ Johnson, John Henry “Pop” Lloyd, Martín Dihigo, Hilton Smith, and John “Mule” Miles were among its memorable stars.

The barnstorming Black teams, including those in the NNL, played everywhere they could get games. As they traveled, they introduced their brand of baseball to Cuba, Canada, Japan, Mexico, and towns across America. Barnstorming, however, was not easy. Dixon explains the difficulties that teams experienced when dealing with racial segregation on the road: “Since African Americans were prohibited as customers in white-owned hotels, motels, and restaurants, . . . players ate irregularly and often sought alternative accommodations. In cities where there were no boardinghouses for African Americans, teams kept traveling, often sleeping and eating on the bus.”

Dixon’s strongest interest lies in his hometown team, the Kansas City Monarchs. One of his books, John “Buck” O’Neil: The Rookie, the Man, the Legacy 1938, gives a thrilling account of the rise of one of baseball’s greatest players and teams while another, Wilber “Bullet” Rogan and the Kansas City Monarchs, tells about one of the game’s best all-around players. As a pitcher, the versatile Rogan “won over 400 games and struck out over 3,000 men. He also ran the 100-yard dash in under 10 seconds and drove the team bus.” Dixon’s coverage of the Monarchs and its players has elevated the historical understanding of the team and placed their legacy at the top of baseball fame. And, much like the Negro leagues, Dixon travels the country drawing crowds to revel in a forgotten but important aspect of American history.

Dixon contextualizes much of his work on Negro leagues within the realities of segregation and racism in America, often exposing the suppression that diminished the growth of the Negro leagues despite the abundance of talent. In his book The Dizzy and Daffy Dean Barnstorming Tour: Race, Media, and America’s National Pastime, he highlights the racially biased media coverage of the Negro leagues, recounting how newspapers marginalized Black players and labeled them as inferior. Dixon contends that “the Monarchs, in spite of having four future Hall of Fame inductees in their lineup, opened the 1938 season with lackluster crowds due to the disparaging newspaper coverage leading into the season.”

Yet the Negro leagues continued. When the NNL stopped in 1931, other leagues stepped in until Major League Baseball completely desegregated in the 1950s. Part of the legacy of the Negro leagues is that the variegated businesses and partnerships developed despite isolation from mainstream culture and the obstruction of economic and political gains. The teams formed a transient body of professionals who created communities as they traveled in the face of institutionalized racism. Thanks to dedicated historians like Phil Dixon, their stories will be remembered and celebrated by Americans whenever and wherever they are heard.