For generations of students who first encountered George Orwell in assigned readings of Animal Farm and 1984, he endures in memory as perhaps the palest man in English letters.

His face seemed nearly spectral as it greeted readers from his author photo—those sad sunken eyes and wan cheeks, their pallor dramatized by a thin, dark moustache that stood out like a skein of geese across a winter sky.

Orwell didn’t look like a man who got out very much, an impression that was grounded, to some degree, in fact. He was a furiously prolific writer, churning out more than a dozen volumes of fiction, memoir, and essays in a life that lasted only 46 years. It was a pattern of production that often fastened him to his desk, and his chronically sick lungs, which led to his death in 1950 after a struggle with tuberculosis, conspired to keep him inside, too.

Nevertheless, like Robert Louis Stevenson, a frequent convalescent who miraculously marshaled his strength for hiking and camping, Orwell indulged an alternate life as an outdoorsman. He’s perhaps our most underappreciated commentator on nature, his writings about animals and agrarian life eclipsed by his reputation as a dystopian.

Orwell’s dueling identities as a brooding scribe hunched over his typewriter and an amateur farmer and naturalist point to his principal claim on posterity—his genius for embracing two lives in one. His legacy often reads like opposite sides of the same coin.

As a self-described democratic socialist, Orwell believed in active government, yet his alertness to the excesses of official power informed Animal Farm and 1984, his two masterpieces about totalitarianism. Orwell was a shy populist often awkward with other people, a habitual realist touched by streaks of the romantic, and a creature of London who sometimes found his truest voice in remote rural places.

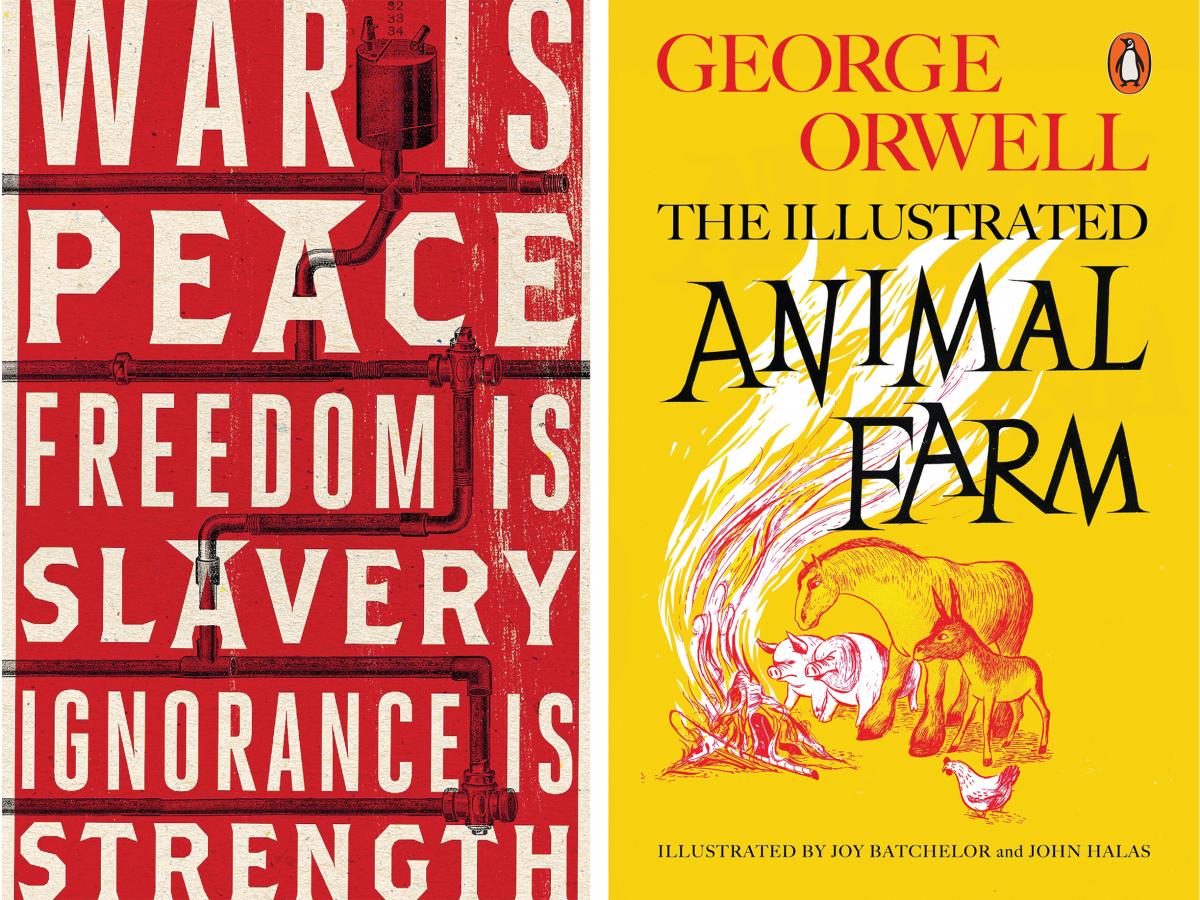

The novels 1984 and Animal Farm encapsulate Orwell’s underlying sense of city and country. The setting of 1984, which chronicles a future society governed through collectivist oppression, is an urban one. In Orwell’s dark vision, the sheer scale of the modern metropolis is dehumanizing, its skyscrapers dwarfing the individual into insignificance. The architectural magnitude of the city, one quickly gathers, is its own form of brutality. In one memorable scene, the novel’s protagonist, Winston Smith, confronts a temple of bureaucracy:

The Ministry of Truth . . . was startlingly different from any other object in sight. It was an enormous pyramidal structure of glittering white concrete, soaring up, terrace after terrace, three hundred meters into the air. From where Winston stood, it was just possible to read, picked out on its white face in elegant lettering, the three slogans of the Party:

WAR IS PEACE

FREEDOM IS SLAVERY

IGNORANCE IS STRENGTH.

Later in 1984, Winston faces an even more daunting monument to the regime. “The Ministry of Love was the really frightening one,” he observes. “There were no windows in it at all.” That simple sentence about the absence of windows is also one of Orwell’s most chilling ones, conveying the sense of claustrophobia that often figures in his work. It’s there in 1984, as a sensitive soul is brought within the inner sanctum of a tyrannical government. A similar feeling of confinement creeps over Animal Farm, as a barn, ostensibly a wellspring of renewal, becomes a shadowy corner of conspiracy and conflict.

The theme of entrapment underscores the beginning of Orwell’s famous essay “The Lion and the Unicorn,” too. It has one of the best opening lines in journalism: “As I write, highly civilized human beings are flying overhead, trying to kill me.” Orwell wrote the essay in 1941 as England endured German aerial bombing. He’s boxed in as the planes circle above him, not quite sure of his fate. It’s a strange form of evil—stranger still, Orwell argues, because it’s been thoroughly domesticated. The Germans pitted as his enemies “are ‘only doing their duty,’ as the saying goes,” he tells readers. “Most of them, I have no doubt, are kind-hearted law-abiding men who would never dream of committing murder in private life. On the other hand, if one of them succeeds in blowing me to pieces with a well-placed bomb, he will never sleep any the worse for it. He is serving his country, which has the power to absolve him from evil.”

Orwell was fascinated by how language could be distorted and abstracted to promote any number of atrocities, with individuals pulverized by the political power of the state. Against this villainy, the writer, insistently stationed at his keyboard and pecking away as the bombs drop, achieves an undeniable nobility. He’s physically imprisoned by the air raid, subject to oblivion at any moment. Yet, as the essay unfolds, Orwell’s mind, musing on everything from English history to stamp collecting to pigeons to crossword puzzles, is free.

The trick here, Orwell implies, is to cultivate language as a liberating influence on culture, not a stultifying tool of officialdom. As he eloquently argued in another, more celebrated essay, “Politics and the English Language,” the best way to keep language morally pure was to keep it simple—its meaning clear, less prone to corruption by politicians.

Written in 1945 and published the following year, “Politics and the English Language” offers a concise seminar on writing well. Orwell lays out six basic rules for good English, most of them grounded on the ideal of simplicity. “Never use a long word where a short one will do,” he implores readers. “If it is possible to cut a word out, always cut it out. . . . Never use a foreign phrase, a scientific word or a jargon word if you can think of an everyday English equivalent.” For Orwell, good writing was a moral imperative:

Modern English, especially written English, is full of bad habits which spread by imitation and which can be avoided if one is willing to take the necessary trouble. If one gets rid of these habits one can think more clearly, and to think clearly is a necessary first step towards political regeneration: so that the fight against bad English is not frivolous and is not the exclusive concern of professional writers.

Simplicity was a primary principle for Orwell, a core quality of his style. As with most aspects of literary expression, even Orwell’s simplicity isn’t as simple as it initially seems. There’s a bare-bones beauty to his prose, but its stark clarity also conveys an underlying sense of urgency. Orwell’s directness on the page revealed a writer who was eager to get to the point, his voice that of a man in a hurry. Perhaps he sensed early on that he wouldn’t live long.

His frankness doesn’t make Orwell a uniformly charming writer. He professed admiration for Jonathan Swift, the eighteenth-century satirist, and Animal Farm’s fabulist narrative of a corrupted revolution by farmyard creatures has some Swiftian touches. Where Swift is disarmingly digressive, Orwell, however, particularly in his newspaper and magazine articles, is usually a ruthlessly efficient rhetorician.

Orwell’s bluntness shaped his personal life, too. Friends remembered him “as prickly, diffident, ill at ease with ordinary people,” writes literary critic John Carey. “According to his brother-in-law, who took him to pubs in working-class districts of Leeds, he was ‘a skeleton at the feast’ and disliked his fellow men.”

Orwell’s embrace, however, of simplicity—in how he wrote and how he spoke—had a more ebullient side. He found its analog in nature, a subject that evoked a surprising tenderness in his vision. “He almost never praises beauty,” Carey notes of Orwell, “and when he does he locates it in rather scruffy and overlooked things . . . the eye of the common toad, a sixpenny rosebush from Woolworth’s. The style he developed in the essays and journalism is the verbal equivalent of these objects. It is plain and simple—or seems to be until you try to write like it yourself.”

While 1984 points to the city as a source of concentrated control, the bucolic landscape of Animal Farm promises, at least initially, a pastoral idyll. In an early passage after the farm animals banish their human masters, they survey the scene of their emancipation:

A little way down the pasture there was a knoll that commanded a view of most of the farm. The animals rushed to the top of it and gazed round them in the clear morning light. Yes, it was theirs—everything that they could see was theirs! In the ecstasy of that thought they gambolled round and round, they hurled themselves into the air in great leaps of excitement. They rolled in the dew, they cropped mouthfuls of the sweet summer grass, they kicked up clods of the black earth and snuffed its rich scent.

If the revolt of Animal Farm is ultimately a failed revolution, its principles perverted by the same moral lapses that create the despotism in 1984, the paradise lost in Orwell’s agrarian allegory is, indeed, a paradise before its desecration. Orwell was drawn to the notion of nature unsullied by the pathologies of politics, and it seems typical of his thinking that the creatures of Animal Farm grow more debased as they grow more human. Like many introverts, he appeared more comfortable with animals than with people, looking to the natural world as a source of solace during times of struggle. Orwell’s brief life included many such trials.

Thomas E. Ricks, author of a recent book about how Orwell and Winston Churchill influenced their time, summarizes Orwell’s origins: “The writer we know today as ‘George Orwell’ was born as Eric Blair in June 1903 in Bengal, India, where his father, the son of an officer in the Anglo-Indian army, was a low-ranking bureaucrat in the Indian Civil Service’s department responsible for overseeing the growing and processing of opium.” His mother was from a French family, the Limouzins, and she was the daughter of a teak merchant, according to Carey.

Orwell’s mother soon took him back to England, where, like many British boys of his day, he was sent to boarding school. Orwell hated the experience at his alma mater, St. Cyprian’s, although he enjoyed rare expeditions away from campus to catch butterflies. “Most of the good memories of my childhood, and up to the age of about twenty, are in some way connected with animals,” Orwell recalled.

Orwell felt bullied by the faculty at St. Cyprian’s, which fed a distrust of official authority that became central to his writing. His later stint as a member of the Indian Imperial Police in Burma, which soured him on colonial rule and led him to the political left, deepened that skepticism. Like many liberals of his day, Orwell went to Spain to support the war against the fascists, where a sniper shot him in the throat in 1937. He returned to England, struggling as a freelance journalist and novelist, not achieving fame until Animal Farm appeared in 1945. His wife, Eileen O’Shaughnessy, whom he had married less than a decade earlier, died the same year, leaving Orwell to raise their adopted baby boy, Richard, as a single parent.

Faced with loss, or the prospect of loss, Orwell often looked outdoors for relief. In August 1939, with the Nazi invasion of Poland just days away, Orwell spent the final stretch of summer “watching over his garden and ducks and chickens, and taking notes on the news as Europe slid toward war,” Ricks writes. “Blackberries are ripening,” Orwell mentioned the day before the invasion. “Finches beginning to flock.”

The war proved hard on Orwell. His flat was bombed, which destroyed many of his books. His manuscript for Animal Farm survived, although, as he confided to T. S. Eliot, the explosion had left it in a “slightly crumpled condition.” However, the war years had also raised his profile, and more readers were noticing George Orwell.

Having a pen name helped Eric Blair preserve his privacy. The origins of his pseudonym are unclear, although “Orwell” is the name of an English river—perhaps a reflection of the degree to which George Orwell’s interest in nature was central to his identity.

In 1946, with the war now over, Orwell published “Some Thoughts on the Common Toad,” an uncharacteristically upbeat essay on the resilience of the earth and the return of spring. It was just like Orwell, though, to hold up the proletarian plainness of the toad to herald a hopeful season:

Before the swallow, before the daffodil, and not much later than the snowdrop, the common toad salutes the coming of spring after his own fashion, which is to emerge from a hole in the ground, where he has lain buried since the previous autumn, and crawl as rapidly as possible towards the nearest suitable patch of water . . . though a few toads appear to sleep the clock round and miss out a year from time to time—at any rate, I have more than once dug them up, alive and apparently well, in the middle of the summer.

Orwell turned to nature once again in the final years of his life, as he worked to complete 1984 and sought out the isolated island of Jura in the Inner Hebrides of Scotland as a retreat. He lived in Barnhill, the rustic house of a friend, with his sister and a nanny along to care for Richard. Although the change of scenery was to take Orwell away from the distractions of London, he seemed to spend a lot of time on Jura away from his writing—gardening, fishing, and exploring instead. All the while, his health was rapidly failing.

“Orwell, a gentle, unworldly sort of man, arrived with just a camp bed, a table, a couple of chairs and a few pots and pans,” journalist Robert McCrum noted. “It was a spartan existence but supplied the conditions under which he liked to work. He is remembered here as a specter in the mist, a gaunt figure in oilskins.”

Despite the hardships—or perhaps because of them—Orwell seemed thoroughly enthralled by his newfound surroundings. “Shot a black rabbit yesterday,” he writes in a May 16, 1946, diary entry from Jura. “Very black, under side grey. They seem to be common about here.”

For a man with compromised lungs, Orwell’s physical activity on Jura was striking. “It is extremely difficult to find straight pieces of timber here,” he laments on June 25, 1946. “Even when cutting pieces for stool legs, I find that any sizeable & strong branch has a kink in it.”

Nothing was easy on Jura, including the completion of 1984. Orwell finished the book, however, as his life faded, forcing him to leave Jura for good. He spent his last days in a London hospital, having married a second wife, Sonia Brownell. Orwell was planning a trip to Switzerland in a last-ditch effort to stabilize his health when he died on January 21, 1950. As he breathed his last, Orwell’s fishing rods rested in a corner of his hospital room.

“There was something undoubtedly romantic both in Orwell’s life and his work, standing as he did in the same revolutionary tradition as Shelley and Byron,” biographer Gordon Bowker concluded. “He was a born adventurer, a man of action, drawn often by the romantic dream. . . . Always, too, was the man who revered the natural world and drew inspiration from it. There stands the romantic Orwell.”