The community garden sits tucked into a quiet corner of Boston: four dozen raised beds on a grassy vacant lot, hemmed in by triple-decker apartment buildings and modest homes stacked shoulder to shoulder. Just down the street, there’s an auto body shop, and around the corner, a gas station. A block away, in an old brick single-story warehouse, a nonprofit distributes donated office furniture to schools and low-income families.

The garden is tended by a cooperative of local African-American women, led by an urban farmer and city bus driver named Kafi Dixon. During the summer it overflows with carrots and corn and collards and peppers. Last year, the women raised 600 pounds of food here, in a part of Boston that often remains invisible to the rest of the city—Dorchester. Boston’s oldest, largest, and most ethnically diverse neighborhood, Dorchester is home to nearly a quarter of the city’s poor. Per capita income is three to four times lower than in wealthier and more attention-grabbing areas like Beacon Hill, Back Bay, and the Seaport District, a brand-new neighborhood near downtown that, over the past two decades, has become part of the largest building boom in Boston’s history.

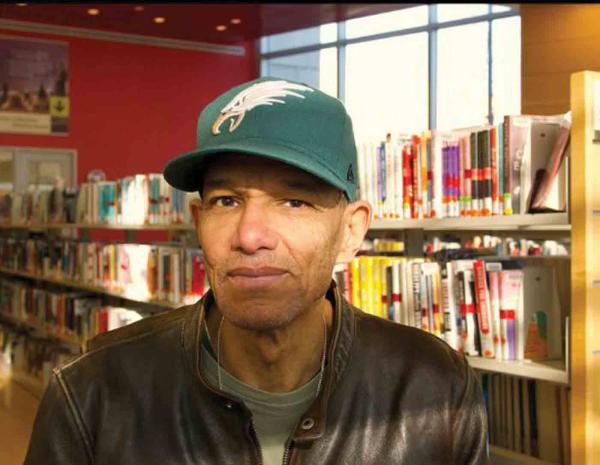

But the factors that keep Dorchester off the radar of many Bostonians are also what put it, and the women’s community garden, at the center of a new documentary. A Reckoning in Boston, which broadcasts nationally on PBS’s Independent Lens, starting January 17, takes as its starting point an adult education program that offers free, accredited humanities courses to low-income people. The narrative focuses on two students in particular: Kafi Dixon, whose driving passion is a connection to the land under her feet and a determination to cultivate a kind of peace there, wresting literal nourishment out of the ground in a city where she has often felt excluded and disempowered; and Carl Chandler, a man in his late sixties, who raised four daughters in a tiny apartment on his own and is now living off a small pension while caring for his young grandson. Deeply thoughtful and perceptive, Chandler considers himself poor but not impoverished. Even as he and Dixon navigate the whirling rapids of their own lives, they find themselves profoundly changed by their encounter with poetry, history, and ancient Greek philosophy.

Following Dixon and Chandler’s lives in and out of the classroom, A Reckoning is about the transformative power of a humanities education, but the film comes to be about much more: the city of Boston, its failures and injustices, its history of violence and trauma, the tide of gentrification washing across impoverished neighborhoods, and the barriers of race and class that bind people in spite of their capabilities or ambitions. “The systems and structures we all live in and that we’re all a part of and complicit with,” says James Rutenbeck, the film’s director, writer, and editor.

An independent filmmaker, Rutenbeck was first drawn to the Clemente Course in the Humanities after hearing one of its graduates speak at a benefit dinner. “She was so charismatic and powerful,” he recalls. For her, the program had opened a path to higher education and a professional career. “Everyone at the dinner was just riveted to her story.” So Rutenbeck, whose previous films have explored life in rural America, health disparities, and immigration, began looking into Clemente. The program was founded in 1995 by the late writer and social critic Earl Shorris to offer economically disadvantaged adults (and, more recently, military veterans and the formerly incarcerated) a rigorous, tuition-free curriculum of philosophy, history, art, literature, and logic. Shorris believed that people who were poor, unemployed, or homeless could benefit just as much as any college freshman from engaging seriously with Plato, DuBois, and Shakespeare, and that they should have just as easy access to the ideas in those texts. The humanities, he argued, help people become “active,” rather than “acted upon,” critical thinkers and freer, fuller citizens able to see themselves and the world differently.

It was that way for Dixon and Chandler.

“Let me tell you about the humanities,” says Chandler. “For myself, and I think for most of the people I went to school with [at Clemente], it’s a vehicle for personal empowerment—which is something that poor people and people of color really need nowadays.” (He traces his own ancestry to Black, Indigenous American, and European roots.) In the film, a poem by Amiri Baraka, “Ballad Air & Fire (for Sylvia or Amina),” accompanies Chandler on a trip to visit his daughter, who is in Philadelphia studying to be a dancer. The poem is about the close connection between love and struggle, between the brevity and pain of life and the intensity of its meaning and joy. Baraka’s words help frame Chandler’s own thoughts about family and community. Lately, he says, he’s been thinking about the philosopher and scientist Blaise Pascal, whose work he’s been exploring on his own. “One of the things that Pascal said is that love and hate alter justice,” Chandler notes, paraphrasing. “That hit home for me.”

Dixon, meanwhile, found answers in Socrates to her long-simmering questions about the role of her own city in the lives of its citizens. A natural entrepreneur, she has spent her adulthood launching ventures intended to help bridge the gap between what public social services provide and what the most vulnerable members of her community need. At nineteen, she opened a mattress store that sold twin mattresses at cost to poor families who were at risk of losing custody of their children over inadequate bedding. Later, she helped start a produce market and organized a milk-buying group to help get healthy food to her low-income community. This led eventually to urban farming, and to the founding of the Common Good Co-Op, the African-American women’s cooperative that maintains the community garden in Dorchester. For Dixon, reading Socrates on how a just, healthy city ought to provide for its citizens was powerful and upsetting. In the film, her recitations of the ancient philosopher’s pronouncements—“It was in order to share after all that we associated with one another and founded a city”—serve as a critique of Boston.

Students in the Clemente Course, funded by Mass Humanities with support from the National Endowment for the Humanities, meet weekly over nine months, earning credits from Bard College in New York. In the decades since Shorris’s first group of 25 students sat down together at the Roberto Clemente Family Guidance Center in Manhattan’s East Village (from which the program takes its name), the course has expanded to more than 30 sites, including several in Massachusetts. The one in Dorchester opened its doors in 2001. And, in 2014, that’s where Rutenbeck headed with his camera. “I had it in my head,” he says, “that if you were in a classroom with 20 people like the woman who spoke at that dinner, there could be so many powerful stories there.”

Art historian Jack Cheng, a professor in the Dorchester Clemente program who also served as its director until 2019, has witnessed many of those powerful stories. He talks about how the students’ decades of life experience deepen their discussions of the texts and lead them down rich and unexpected tangents. The students’ approach to knowledge is different, too: Cheng remembers feeling flummoxed during his first year at Clemente because “a lot of the questions the students asked were basically, ‘How do you know that?’” This was a shift from what he was used to in classrooms of nineteen-year-old undergraduates. “In a college course, you say, ‘Well, it’s in the book,’ and people go, ‘Oh, okay, it’s in the book.’ But with the Clemente students, I really had to go back to primary sources and first principles.” It wasn’t that they were denying the veracity of what he was teaching. “It was more like, they were Foucault,” Cheng says, as in Michel Foucault, the French philosopher whose work addressed the relationship between power and knowledge. “They wanted the archaeology of knowledge,” Cheng adds. “Like, ‘Get me to the source of this so I can truly understand it.’”

Former Clemente students sometimes write to Cheng years after they’ve graduated to talk about how the program helped steer their lives in new directions or to tell him how they’ve continued their education, either formally or informally. “Sometimes they’ll say something like, ‘Riding on the bus is different now, because I’m looking at architecture rather than buildings,’” he says. “You know, the experience of being in a classroom, of expressing your thoughts and being listened to—that changes people.” One memory that sticks with him: a field trip to Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts with a group of Clemente students that included a woman who at the end of every class would ask for help with her bus fare. “She always just needed like 75 cents or $1.50 to get home,” he says. As he and the students were preparing to leave the museum after their visit, he caught sight of her across the lobby, putting a dollar bill into the extra donation box. “And I just thought, ‘That is perhaps the most precious dollar the Museum of Fine Arts has ever received,’” Cheng says.

In the beginning, Rutenbeck was imagining a documentary with lots of scenes like that one. “I was thinking of it as just exclusively humanities,” he says, “that this would be a story of transformation through art, philosophy, history, literature. And that story is very real and powerful, and it’s still in the film.” But the more time he spent with Dixon and Chandler outside of class, the more the threads of that tidy narrative loosened and unraveled. During the five years it took to make A Reckoning, Dixon and Chandler each faced eviction (both had gone through periods of homelessness in the past), and it becomes inescapably clear in the documentary how violence and deprivation have touched their lives. One of the film’s most revealing scenes involves Dixon negotiating with officials at City Hall, where her request to grow food on abandoned lots in Dorchester and nearby Jamaica Plain, a rapidly gentrifying neighborhood, is repeatedly met with administrative deflections.

As a white suburban man, Rutenbeck found himself struggling to process Dixon’s experience of a city that, as he says in A Reckoning, “I’ve always loved but never truly understood.” Early in the film, he cites a data point that hangs over the rest of the narrative: In Boston, the median household wealth for whites is $247,500, and for Blacks it’s $8, according to estimates made in one study.

“It’s odd,” Rutenbeck says now. “There’s this parallel society that, living where I live, I’m totally insulated from.” Newton, Rutenbeck’s hometown, is less than ten miles from Dorchester, but a world away. “The things that were happening to Kafi and Carl, particularly evictions and housing insecurity, I didn’t really understand,” he says. He began to question whether he could make this film, or whether he should even try. In the end, what he realized was that he couldn’t do it alone. He asked Dixon and Chandler to join as producers, formally cementing an advisory role they were already stepping into.

Partly at their urging, Rutenbeck began bringing his own voice into the documentary, explicitly laying out his own relationship to the racial and economic inequalities that were playing out on the screen and in their lives. He was apprehensive at first. His previous films had always maintained an observational distance, allowing the people in them to tell their own stories. But, in this case, he realized, that distance had become a way to protect himself from the hard questions the film kept raising. For A Reckoning to work, Rutenbeck needed to make himself vulnerable. “After a while, James started hearing us,” Chandler says. “I mean, he always heard us, but, you know, really hearing us, in his core.” Dixon concurs. “We asked James to show that hidden part of Boston,” she says, to be an active witness. “And, mind you, we were asking him to have his own reckoning, and to talk about a history—and a present—that is not talked about. A history that could inform a better society.”

With the first-person framework, the rest of the film fell into place, Rutenbeck says. The result is a documentary that combines classroom discussions, classic texts, students’ lives, and archival footage of racist flashpoints in the city’s history to explore the realities of entrenched injustice. But the film also examines the power of knowledge and the inspiration that can be found in the humanities as people struggle to figure out how to live and survive. In the end, A Reckoning resists easy answers or a clear resolution that would leave audiences feeling comfortable. It’s a “more authentic document” that way, Rutenbeck says, part of a conversation that is necessary, but not over. Much like education itself.

(A Reckoning in Boston is streaming online at PBS and on the PBS app through February 22, 2022.)