Does photography have a particular relationship to the real? Most of us assume it does. Unlike images made by hand—paintings, for example—photographs seem to provide an objective record of what was directly in front of the camera at a particular time and place. For African Americans, who have not always had access to the means of representation or the freedom to define and distribute their own images, photography’s assumed realism has been a crucial part of efforts to gain visibility and to replace negative and damaging images with more positive ones. For Louis Draper, who grew up in segregated Richmond, Virginia, in the 1930s and ’40s, navigating these expectations about photography’s realism posed a unique challenge.

As a Black photographer working primarily during the civil rights era, Draper wanted to foreground his experiences as an African American. At the same time, Draper worried that doing so would result in his photographs being looked at as documents rather than as works of art.

Draper wanted his photographs to be appreciated for more than just their realism. He explains, in a typescript from 1986, “In my beginning years I was plagued by various questions about reality and how responsible I needed to be in depicting it.” In addressing this problem, Draper took inspiration from a credo by abstract artist Paul Klee: “Art does not reproduce the visible, but makes visible.” Throughout Draper’s career, this insight into the creative act of seeing remained a touchstone.

Draper began pursuing photography while attending Virginia State College (now University) in the early 1950s. He majored in history and journalism at the historically Black college in Petersburg. In his junior year, Draper secured a position as a reporter on the student newspaper, the Virginia Statesman. His father, an amateur photographer in Richmond’s East End, sent him a camera. Lacking any formal training, he mostly used it to take straightforward photos that documented events around campus. Everything changed, however, when Draper came across a copy of Edward Steichen’s seminal 1955 photography catalog for the Museum of Modern Art’s “The Family of Man” exhibition, left fortuitously in his dorm room.

Draper ruminated, in a 2001 interview with me, on the significance of discovering this landmark work: “That was the beginning of my photography education. Instead of studying, I read The Family of Man. I was just enthralled by that book. Until that time, I was really floundering around, I had no clue as to what I wanted to do. This book solidified things for me. From it I learned that I really wanted to be a photographer. So I went to the library and read everything that I could get my hands on. Many of the photographers whose works I admired were living in New York City, so then I concentrated on trying to get to New York. I dropped out of college, as I just wanted to go to New York. That was the only thing that mattered to me.”

Draper first sought instruction at the New York Institute of Photography but quickly switched into an independent photography workshop offered by Harold Feinstein. Under the mentorship of Feinstein, and later W. Eugene Smith, Draper began to flourish as a photographer. He also began to sort out how responsible he needed to be in depicting reality.

One of the most significant lessons Draper learned from Feinstein was to “photograph where you are involved.” To Draper, this meant depicting what he knew best: African Americans. But selecting a subject was only the first step. Draper was aware of how photography, especially the pictures that circulated in contemporary newspapers, magazines, and books, tended to pathologize African Americans and depict them in monolithic and overly simple terms. Not wanting to replicate negative stereotypes that overlooked the vitality and complexity of the African-American experience, Draper sought a different tactic. A photograph from 1965 that Draper took of an African-American laborer in New York City’s Garment District epitomizes this aim.

Because of “competition with skilled white ethnics,” many African-American men in New York at this time, as sociologist Roger David Waldinger explains, were forced to work “push[ing] racks of clothes through the streets of the Garment District.” Although the work was “low-prestige” and “low-paying,” Draper did not depict these workers as destitute or debased. Instead, he emphasized their humanity. “I didn’t want to make them anonymous people pulling carts and so forth,” recounts Draper. “I was trying to get at something about a thought pattern or some internal thing that they were about as individuals.”

Much of this he accomplished in the darkroom. From Feinstein, Draper learned to use film development to turn a photographic negative into a print that reflects the artist’s creative vision. Understanding that photography is an imaginative, not imitative, medium, and therefore not limited to the transitory subject that lies in front of the camera, Draper used the darkroom tools of cropping as well as burning and dodging to transform his images into expressive works of art that, while tethered to the real, also transcended the medium’s documentary purposes.

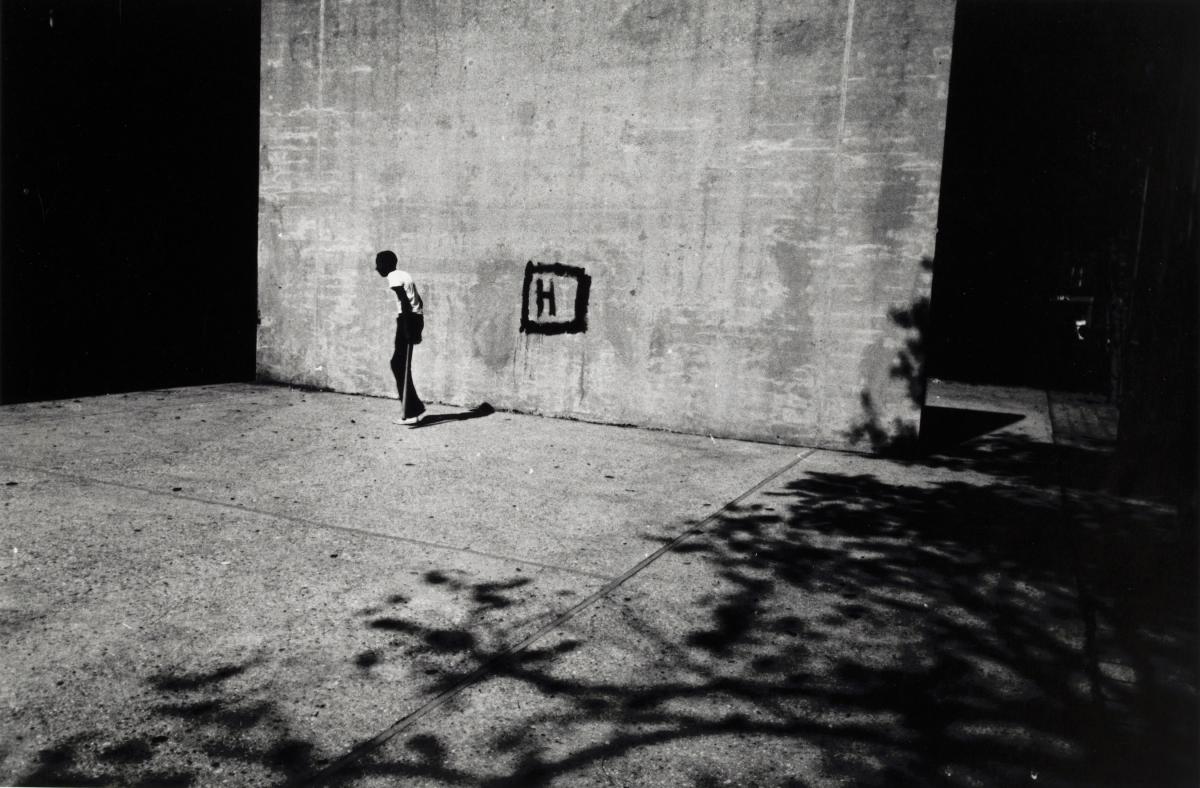

Draper’s contact sheets and negatives, now housed as part of his archives at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond, provide insight into the scope and significance of his creative process. For his Garment District photograph, for instance, Draper cropped out much of the urban setting, including the clothing, so viewers are encouraged to see the man in this photograph not in terms of his position in the “urban underclass” but as an individual. Likewise, for images such as Boy and H, Harlem, from 1961, in which a teenage boy saunters away from the letter “H” crudely scrawled within a black square on the wall behind him, Draper burned in the dark shadows that forebodingly frame both sides of the print. This encroaching darkness transforms the photograph from a straightforward document of a young boy playing stickball to a more complex depiction of childhood. The final image differs considerably from the more moralizing images of African Americans that circulated contemporaneously in the print media.

Draper imparted his darkroom skills and, especially, his “style of printing: black blacks, black on black,” as his friend Ray Francis recalled, to other members of the Kamoinge Workshop. Based in New York City, this collective of African-American photographers was formed in 1963, within, as Draper later explained, the “volatile political climate of the 1960s and the emerging African consciousness exploding within us.” Kamoinge—a word from the Gikuyu language, spoken by Kikuyu people of Kenya—means “a group of people acting together.” Foremost, the group was a community of friends who casually gathered in each other’s homes, usually on Sundays, to eat, listen to music, and critically discuss photography.

Members often used meetings to debate the aesthetic merits of each other’s prints as well as the advantages of approaching their subject matter through such formal means as realism and abstraction. Draper fondly recalled some of these conflicts: “There were many heated debates. If the work wasn’t up to snuff we would let you know. There were many times when I left there with my head hanging very low because I hadn’t done the best. But you lick your wounds and you go out and you do better work, because that was what it was about.”

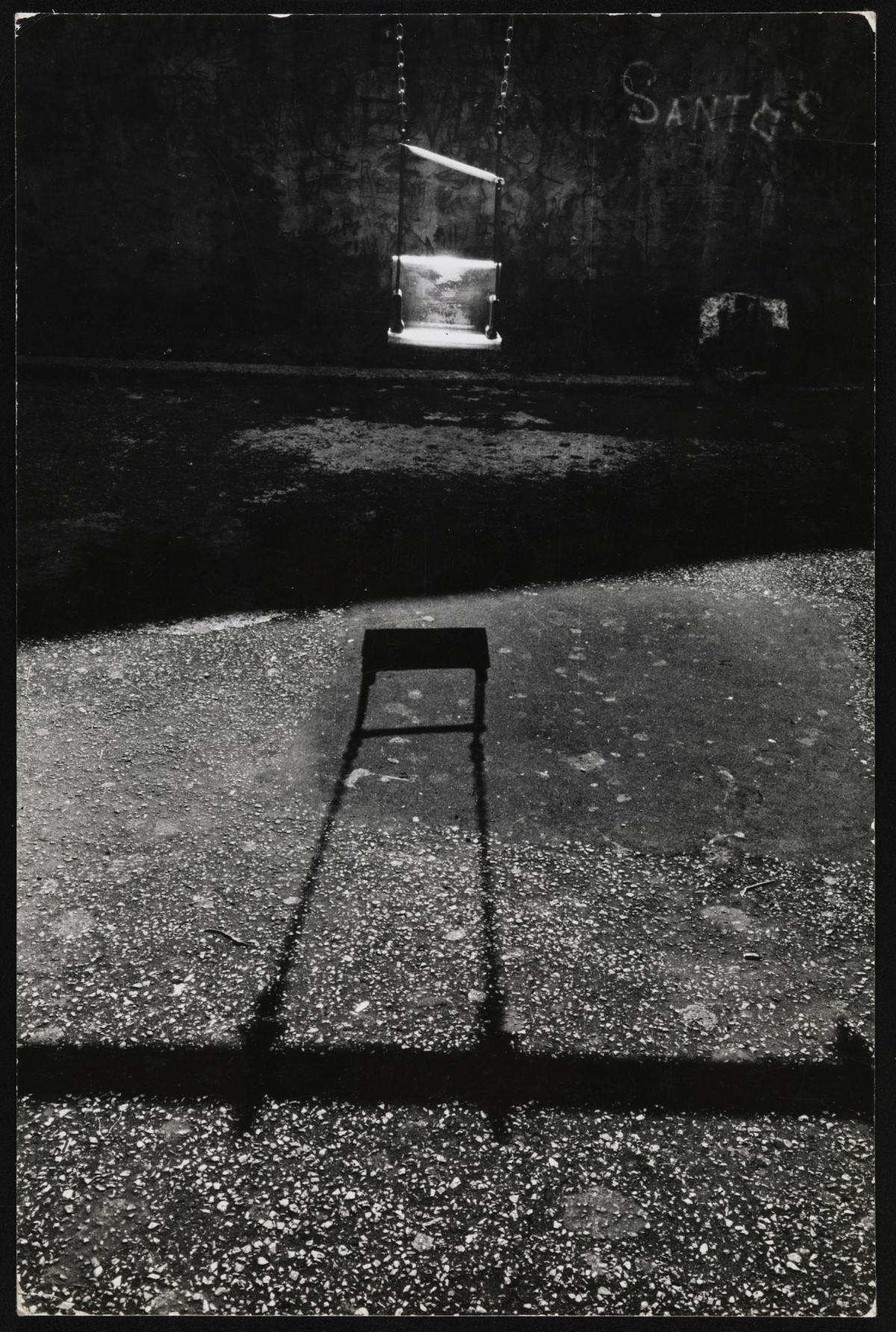

Though members often disagreed with one another about the purpose and intention of their work, there was no set ideology, artistic or political, to which the group subscribed. Both realism and abstraction could be found in work associated with the workshop, as the actual practice of its members, including Draper, proved quite fluid. Draper’s photograph Untitled [Santos], from 1967, exemplifies this flexibility. The subject, a playground swing set, is perfectly recognizable, but the meaning is anything but literal. Bifurcated, the image, which pits dark against light, is a study in formal contrasts. In the top half of the picture, a strange reflective light emanating from swing’s seat ruptures the print’s penetrating darkness. Likewise, in the picture’s lower half, the striking lines projected by the dark shadows of the swing set breach the print’s projected luminosity. This formal play of dualities, alongside the poetic “Santos,” scrawled radiantly in the background, imparts an understanding of photography that, once again, transcends its assumed realism.

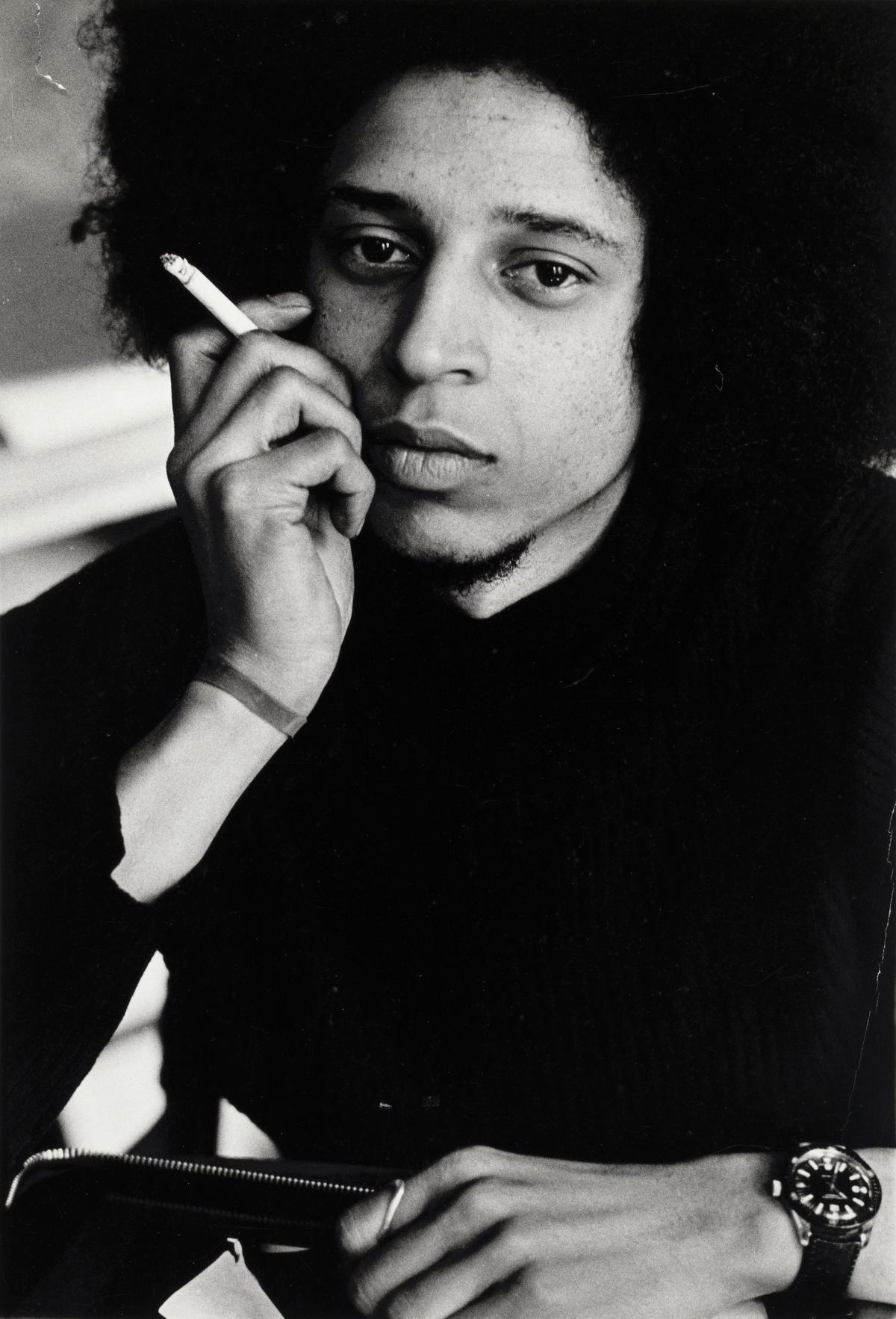

Draper’s commitment to photography as a form of art did not keep him from sometimes working in journalistic contexts. In 1971, Essence magazine sent him on assignment to Mississippi to photograph Fannie Lou Hamer, the well-known civil rights activist. Hamer had gained notoriety for her work on voter registration drives, for which she was arrested and severely beaten by police in 1963, but Draper elected not to contextualize her within the immediacy of this civil rights history. Instead, as he had done for his photograph of the African-American laborer in the Garment District, Draper focused on Hamer as a unique person. He used a closely cropped depiction of her face, which fills the entirety of the picture frame, to distinguish her individuality. The picture “makes visible” her remarkable strength and grace. Draper’s now iconic photograph appeared as the lead image with the article “Fannie Lou Hamer Speaks Out,” in the October 1971 issue of Essence.

Draper would continue to impart his unique artistic vision—grounded in the particularities of his African-American experience, yet not limited by it—for years to come. From 1978 to 1982, he taught and coordinated photography courses for schools in New Jersey through the Creative Resources Institute. In 1982, he was invited to join the faculty at Mercer County Community College, where he continued to teach until his untimely death in 2002. His legacy to “make visible” lives on today in his vast archives at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, where both scholars and the general public can learn from more than 6,600 items, including photographs, negatives, contact sheets, slides, computer discs, audiovisual materials, and camera equipment related to Draper’s singular life and practice.