In a 1918 storybook, Beatrix Potter describes an encounter between a humble country mouse named Timmy Willie and his urbane counterpart, Johnny Town-Mouse.

The two meet when Timmy Willie falls asleep in a hamper and is transported to town, the unwitting passenger of a weekly produce delivery. After escaping from an angry cook, displeased to find vermin in her vegetables, he is housed and fed by Johnny Town-Mouse. The pair grow friendly, but as Potter recounts, their tastes prove to be hopelessly incompatible. Disturbed by the commotion of town, Timmy Willie hitches a ride back to the country as soon as he is able. On a later visit to see Timmy Willie, Johnny Town-Mouse declares that the country is “too quiet” and ends his trip early.

Though The Tale of Peter Rabbit is Potter’s most famous work—the book has sold more than forty million copies—Johnny Town-Mouse stands apart for providing a glimpse into the psyche of its author and illustrator. As Potter discloses on the final page, the sentiments of Timmy Willie echo her own preference for the tranquility of rural life: “One place suits one person, another place suits another person. For my part I prefer to live in the country, like Timmie Willie.” It was a lesson that Potter had to learn the hard way, for this self-avowed country mouse was born and raised in the bustling suburbs of London. It would take Potter until her midlife to renounce the capital for good and relocate to England’s Lake District, the northwest region that served as the backdrop of Johnny Town-Mouse and several of her other “little books.”

The landscapes of the Lake District would also inform Potter’s lesser-known second act as a farmer and conservationist and would inspire a legacy that extends well beyond the reach of Peter Rabbit. When the British conservation movement was still in its youth, she used her wealth and influence to protect the land and traditions of her beloved countryside. Anyone who has basked in the sublime beauty of the region, with its crystalline lakes and picturesque cottages, has Potter to thank for her activism and foresight.

Helen Beatrix Potter was born in 1866 and raised in 2 Bolton Gardens, a multistory townhouse in Kensington. In the early 1800s, the area was a semirural village on the fringes of London. By midcentury, it was in the process of being converted into a suburban enclave and would more than double in population over the course of the century. (It is now an incorporated part of the city.) As Potter recalled in one of the many journals she kept during her lifetime, by her teenage years, the last vestiges of farmland had already been cleared away to make room for new homes and train lines.

Like other Kensington transplants, the Potters belonged to the upper middle class. Rupert Potter was a barrister whose family owned a successful textile printing business. His wife, Helen, was the daughter of a wealthy cotton merchant. Both were raised in Greater Manchester but shed their northern trappings in favor of London sophistication. Rupert and Helen relished the London social scene and were frequently out of the house, conferring Helen Beatrix and her little brother, Walter Bertram, to the care of nursemaids and governesses. Shut up in 2 Bolton Gardens, Beatrix and Bertram, as the siblings were known, were left to find their own sources of amusement. The large upper-floor nursery became their private universe of exploration and play, and it was here, amid piles of illustrated books and magazines, that Potter discovered her talent and passion for drawing.

The gift of artistic expression was one she came by naturally. Helen made embroidery and watercolors and Bertram grew up to be a professional oil painter. Rupert dabbled in drawing and painting and was a devotee of the emerging medium of photography. He was elected to the Photographic Society of London in 1869 and took reference photographs for his friend Sir John Everett Millais to use in composing his lush canvasses. Because of her paternal connections, Potter met the pre-Raphaelite painter in her girlhood and recalled that Millais had been an early admirer of her drawings, praising them for displaying a rare power of observation.

From the beginning, Potter enjoyed studying animals and did not have to look far to find compelling subjects. She and her brother kept a number of different pets, including dogs, birds, reptiles, and rabbits. Potter spent hours recording their expressions and movements, lavishing particular attention on the rabbits Benjamin Bouncer and Peter Piper, whose names and appearances would inspire the later characters of Benjamin Bunny and Peter Rabbit. The siblings were natural-science enthusiasts and piled their nursery high with jars of flowers, insects, rocks, and fossils, among other curiosities. As a teenager, Potter grew especially interested in mycology, the study of fungi, making meticulous watercolors of mushrooms with the aid of a microscope and running experiments on spore germination. She eventually tried to publish her findings in her late twenties with the Linnean Society of London, but her research was met with indifference from its all-male members, who were wary of an amateur woman scientist. In the face of their tepid reception, Potter withdrew the paper and never again attempted to publish it. Had there been more opportunities for women in the sciences in the 1800s, the natural historian Richard Fortey speculates that “Potter might have spent the rest of her life as a pioneer mycologist.”

Despite her outsider status, Potter was able to accumulate an impressive collection of specimens thanks to the family’s frequent trips away from London. In the spring, the family went to the southern English seaside. To beat the summertime heat of London, Rupert and Helen rented out 2 Bolton Gardens and decamped to the north—first to Scotland, and, later, to the Lake District. During these summer pilgrimages, Potter roamed freely, collecting flowers, catching butterflies, and filling sketchbooks with copious notes and drawings. As her journals and letters record, being out-of-doors filled her with a sense of fulfillment and happiness that eluded her in London. Reminiscing on her time in Scotland, she wrote: “I remember every stone, every tree, the scent of heather, the music sweetest mortal ears can hear, the murmuring of the wind through the fir trees. . . . Oh, it was always beautiful, home sweet home.” The destruction of the family residence in Kensington by World War II bombing, by contrast, prompted little nostalgia or sadness. “I am rather pleased to hear it is no more,” Potter said in a letter from 1940. The townhome was, she added, nothing more than her “unloved birthplace.”

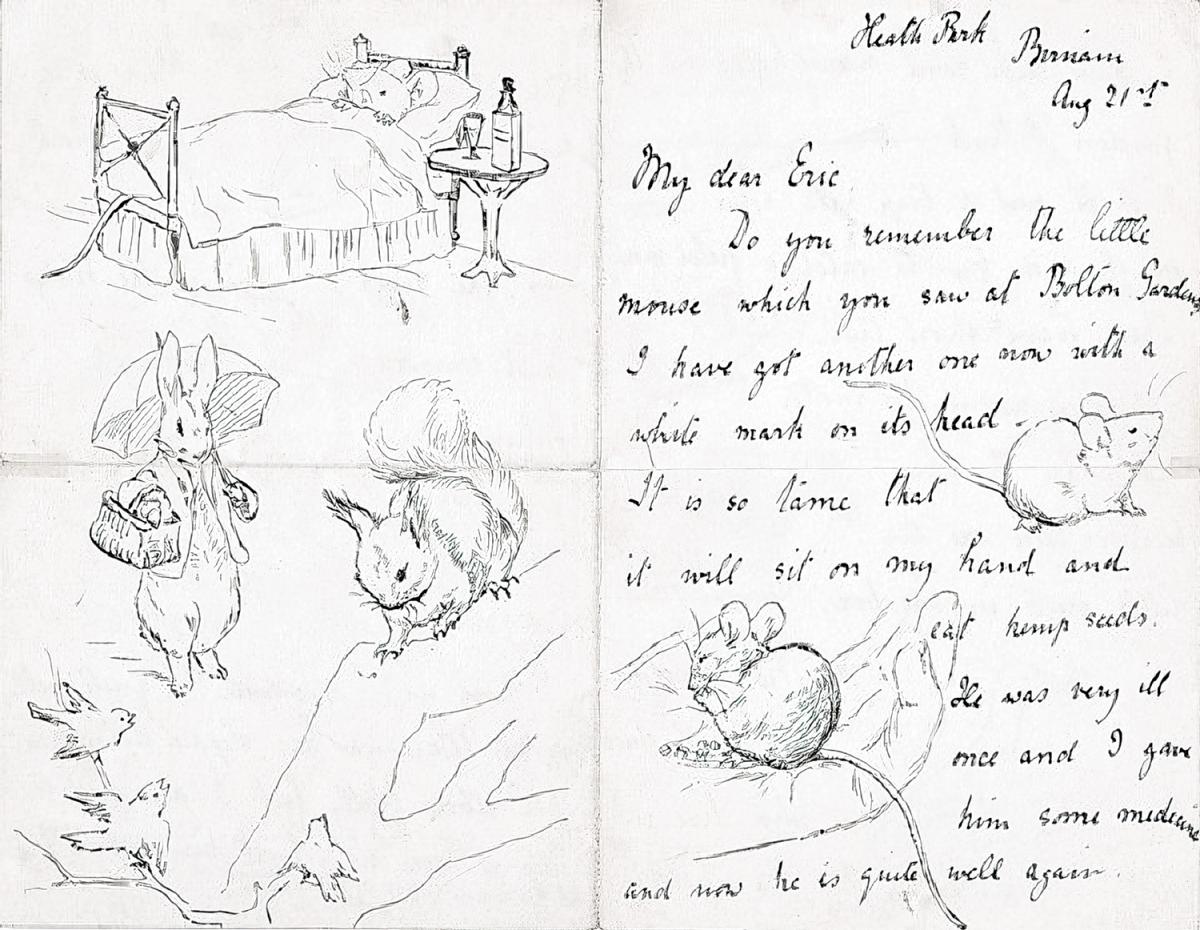

It was during one of her idyllic vacations that Potter began laying the foundations for her future career as a children’s book writer. While in Cornwall in 1892, she composed the first of her “picture letters” to Noel Moore, the four-year-old son of her former governess, Annie, outlining her trip in words and small intricate illustrations. The same year, back in London, she sent another picture letter describing an encounter between Benjamin Bunny and a wild country rabbit. A year later, this time inspired by the antics of Peter Piper, she sent Noel a fantastical story of a rabbit named Peter and his three companions, Flopsy, Mopsy, and Cottontail. She would continue sending stories and sketches to Noel and his siblings throughout the 1890s, crafting early versions of characters in Peter Rabbit, as well as The Tale of Benjamin Bunny, The Tale of Squirrel Nutkin, and The Tale of Mr. Jeremy Fisher.

During the same decade that she penned her picture letters, Potter made her first attempt to earn a living from her art. An unmarried woman chafing at life with her parents, and at her duties tending to the “unloved” 2 Bolton Gardens, she began selling her drawings and designs to a greeting card company in the hope of gaining some financial independence. With encouragement from Annie, she made a further bid for financial autonomy in 1900, when she decided to try her hand at the growing children’s book market. While visiting the Moore family that year, Annie suggested to Potter that her picture letters had the makings of an entertaining book series. Intrigued by the idea, Potter asked to borrow her original correspondence—all of it lovingly saved by Annie’s children—and considered how their contents might be transformed into full-length books. Embellishing and elaborating the imaginative episodes she had relayed to Noel about her pet Peter Piper, she developed a manuscript entitled The Tale of Peter Rabbit and began shopping it around to prospective publishers.

The book sparked immediate interest, but editors rejected Potter’s proposed format of a small and cheaply printed book teeming with black-and-white illustrations. With no deal in sight, in 1901, Potter opted to self-publish 250 copies with her own funds. The fate of Peter Rabbit changed only later that year, when a friend of Potter’s urged the publisher, Frederick Warne, to take a second look. After successfully brokering a compromise on the format—with Potter agreeing to pare down her text, lose some illustrations, and color those that remained—Fredrick Warne & Co. became the official publisher of the now-famous story of the mischievous bunny rabbit. On October 6, 1902, Potter wrote to one of the Moore children to share the exciting news: Peter Rabbit would soon be in their local bookstores. What was more, Warne had already started a second printing to meet high demand.

The partnership between Potter and Warne would prove to be incredibly fruitful: Warne released at least one new storybook by Potter annually for the next 11 years. A keen entrepreneur, Potter also had the good commercial sense to license her characters for use in toys, fabrics, and other merchandise. Long before J. K. Rowling, English children were beset by Potter-mania, snapping up board games and stuffed animals inspired by Peter Rabbit, Jemima Puddleduck, and other favorite Potter characters. In her mid-thirties, Potter had finally secured the means to become independent—if not yet the emotional mettle.

It would take the promise and loss of marriage to finally remove Potter from the family home. While working on her books, she had formed a close friendship with her editor, Norman Warne. Over time, the friendship blossomed into something more tender, and, in 1905, Norman proposed marriage by letter. Potter accepted and the pair began hatching plans to purchase Hill Top Farm, a working farm in Near Sawrey—a village in the Lake District that Potter had become familiar with in her travels. The engagement should have been happy news in the Potter household in view of Beatrix’s age. (She was by then nearly forty and well into the territory of “spinsterhood” by Victorian standards.) But Helen and Rupert bitterly opposed the union on the grounds that publishing was not a suitably genteel profession for a potential son-in-law. Before they had the chance to change their minds, tragedy intervened. Norman took ill and passed away, putting an end to any possibility of a wedding. Far from draining Potter of her resolve, grief sharpened her determination to stake out the life that she and Norman had dreamed of. She pooled her earnings together with a small inheritance from her aunt and went ahead with the purchase of Hill Top. After almost four decades in Kensington, Potter headed north, reversing the path taken by her parents.

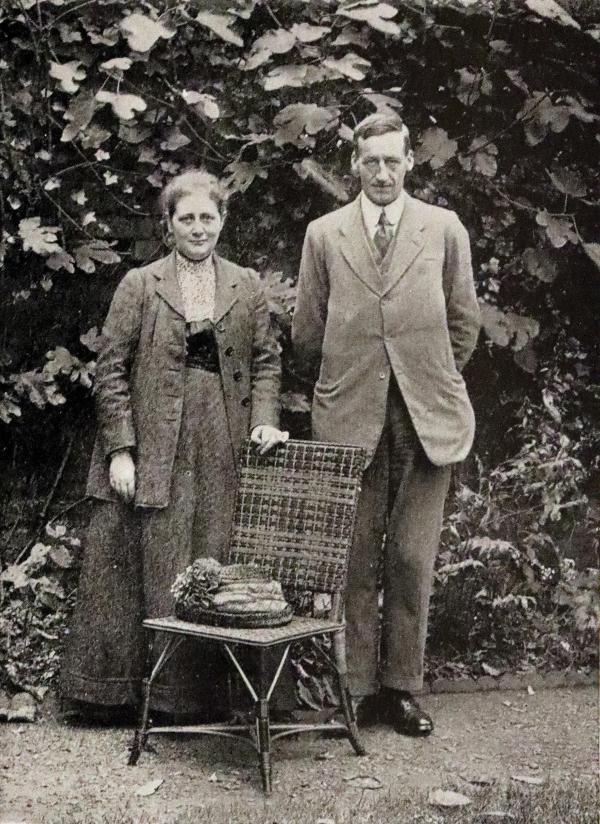

During her first decade in Near Sawrey, Potter remained ensnared in the web of familial obligation. She was frequently called away to help her aging mother and father but continued all the while to plant roots in the village. Elated by her purchase and renovation of Hill Top, she invested her incoming royalties in more property, including the adjacent Castle Farm. She also chose to marry the local lawyer, William Heelis, who helped orchestrate the sale. At the age of forty-seven, Beatrix Potter wed Heelis against the advice of her parents, who deemed a country solicitor to be even lower than a publisher. The following year, just before the outbreak of World War I, her father passed away, and Helen lived out the rest of her days in the Lake District.

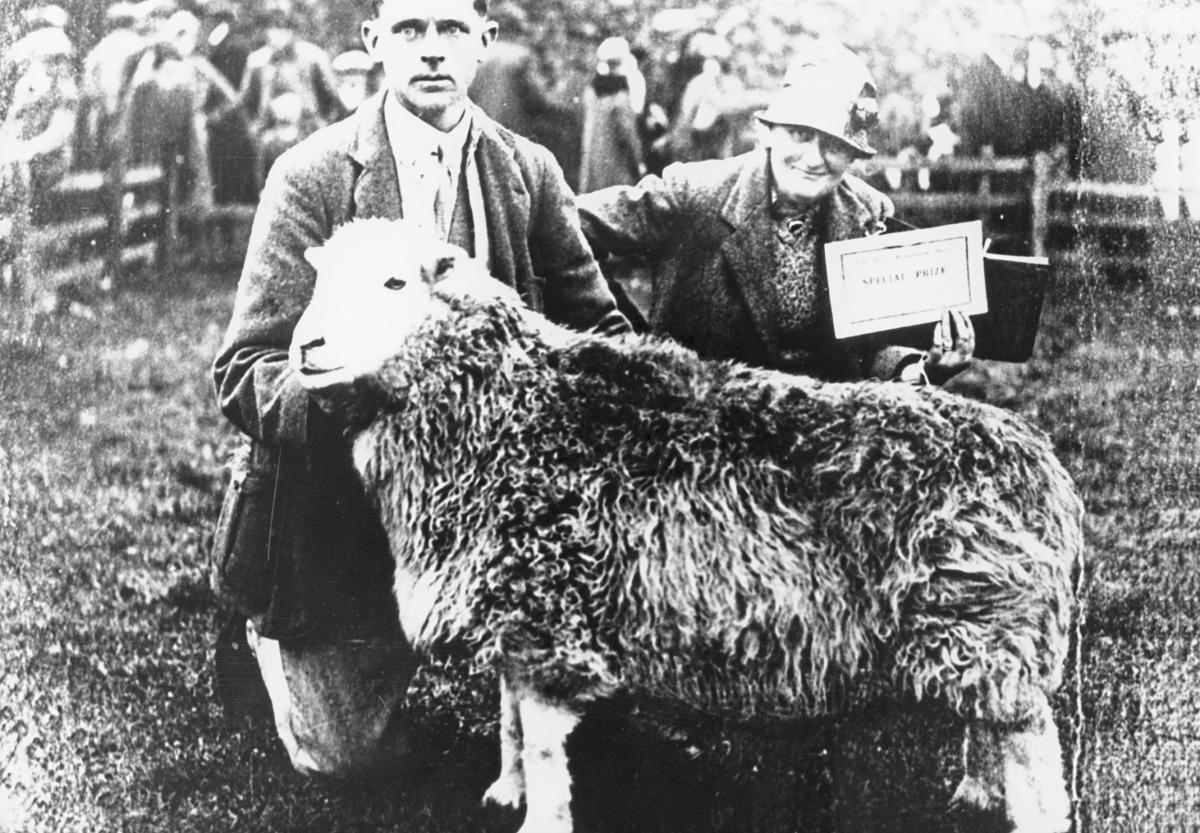

Known to the community by her married name of Mrs. Heelis, Potter gradually turned her attention away from writing to matters more immediately at hand. In order to manage her new properties, she learned the business of farming, wielding the straw-chopping machine and reading up on animal diseases. She was also an eager student of the science of animal breeding, and with the help of an expert shepherd, started an exacting program at Hill Top to breed Herdwicks—a type of sheep native to the Lake District and known for their coarse woolly coats. Potter’s lambs and ewes regularly swept prizes at livestock fairs, and for her efforts to advance the heritage breed, she was the first woman to be elected president of the Herdwick Sheep Breeders’ Association. (She died before she could actually take office.)

On top of managing the farms and animals already in her possession, in her final decades, Potter set about acquiring as many buildings and lands as she could, believing that this was the best means of contributing to nascent Lake District preservation efforts. The region was a favorite destination of southern tourists, and by the twentieth century, the traditional architecture and agriculture of the region were under threat of extinction. Sensing their vulnerability, Potter leveraged her wealth to conserve local history and nature by partnering with the National Trust, an organization founded in 1895 to care for heritage sites across England, Wales, and Northern Ireland. At the end of her life, she bequeathed the Trust a staggering collection of 14 farms and four thousand acres of land. The gift was significant not only for safeguarding the Lake District with its size and scope—it included important examples of vernacular Lakeland architecture and swathes of fragile ecosystems—but also for ensuring the longevity of the Trust. The Heelis bequest remains the largest single donation to the Trust in the Lake District and sent an important message of support for the organization that inspired further contributions across the twentieth century. When Potter passed, in 1943, her ashes were scattered on her lands, joining her memory forever to the place that she treasured most in the world.