The third floor of the Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C., can hardly contain “Alma W. Thomas: Everything Is Beautiful.” The more than 170-work retrospective charts Thomas’s career from her understated still lifes to her kaleidoscopic abstractions, underlining the beauty she saw in the material world and imagined in a cosmic one.

Thomas, born in Columbus, Georgia, in 1891, was a keen observer of the world around her. Growing up Black in an all-white suburb, she surely sensed the racial tensions afoot. The Atlanta Race Riot of 1906, which left dozens of African Americans dead, broke out just a year before her family left for Washington, D.C.

And yet Thomas’s reflections on her childhood tended not to social unrest but to the splendors just beyond her window: the delicate play of light in the garden, the vibrant flowers underfoot. “The wind would dance the leaves together and make it dark,” Thomas writes, “then the light would come around.”

Thomas owes her eye for beauty, in part, to her mother, Amelia, a dressmaker whose elaborate gowns enliven Alma’s childhood photos. The Phillips show includes a dress Alma wore to an exhibition opening years later. The long-sleeved empire-waist gown, patterned with a green and orange geometric design recalls her mother's fanciful dresses.

“Thomas tied her mother’s craft to emotions of love and joy,” writes Rebecca Bush in the exhibition catalog, “recalling ‘she loved to sew for us, and her sewing was just like my painting, she was happy when she was creating something very beautiful for us.’”

In Washington, living within walking distance of the Phillips, Thomas enrolled at Howard University and, in 1924, became the school’s first fine arts graduate. She spent the following 35 years working as a middle school teacher in the Shaw neighborhood, painting in her spare time and helping to create the Barnett Aden Gallery, one of the first Black-owned galleries in the country.

“Thomas was a person who was working her entire life,” says Renée Maurer, who curated the exhibition for the Phillips. “She didn’t see anything as an ending.”

While Thomas’s work in the 1950s and early ’60s is often overlooked, it reveals much about the subtleties that caught Thomas’s eye and the beauty that continued to captivate her.

Among the most striking works from this period is They Laid Him in the Tomb, a painting of the crucifixion in hinted yellows and jet blacks, bodies suggested rather than delineated. In the Phillips show, the work is framed between Saint Cecilia at the Organ (Etude in Brown) and Etude in Blue, two equally stirring canvases, one in shades of ochre and scarlet, the other, cadmium blue and white.

On the same wall hangs Sketch for March on Washington, one of the few paintings in Thomas’s oeuvre addressing, on its face, a social issue. In it, a mass forms, faces obscured, under layer upon layer of picket signs. But the signs are conspicuously blank and the mood decidedly muted.

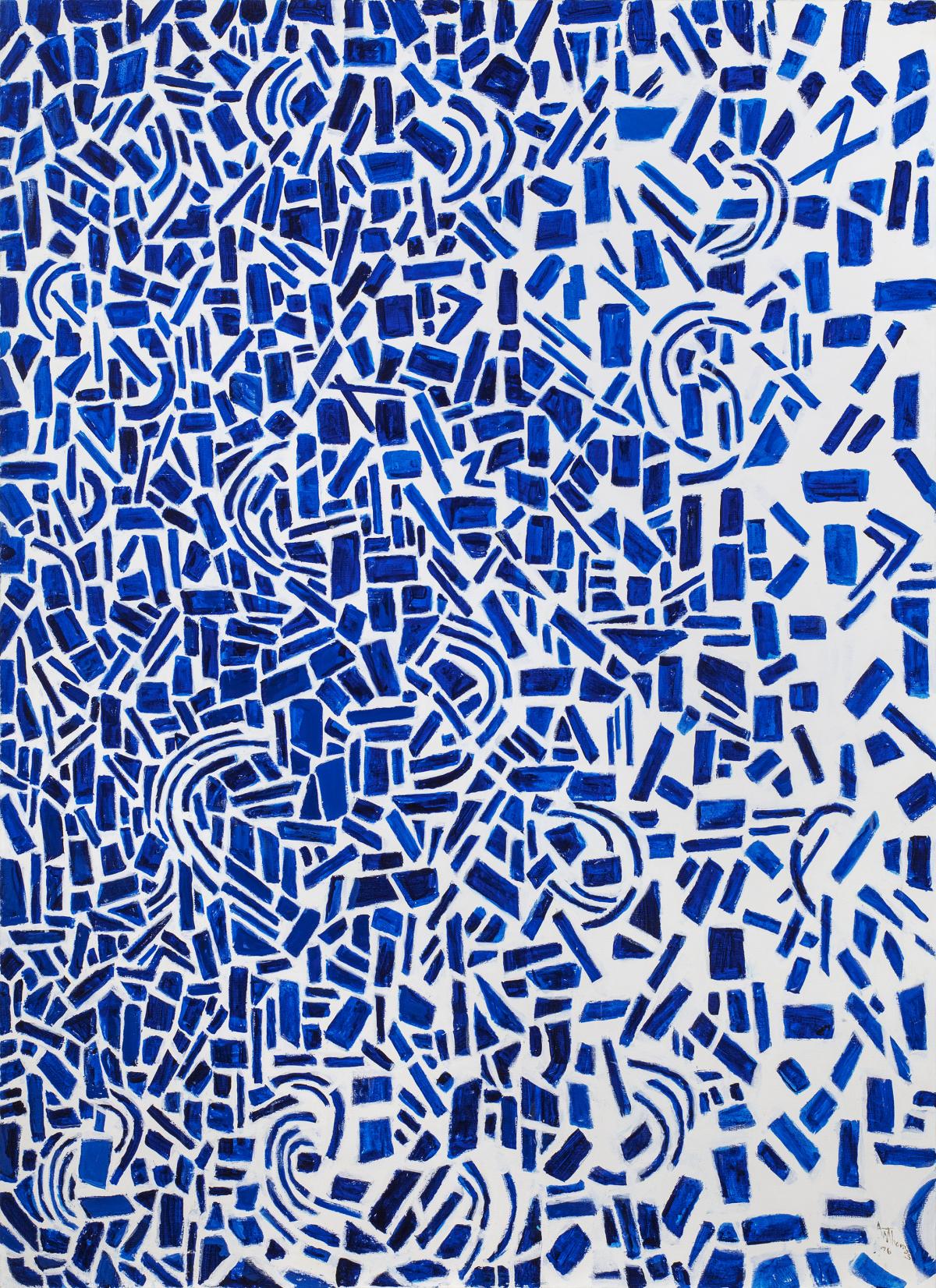

It was only when Thomas turned from figuration toward abstraction that she rose to acclaim as an artist. When the solidity of her line gave way to broken, vibrant colors, the beauty she had long seen emerged.

This shift is best illustrated in the Phillips show in a side room where Still Life with Vases and Flowers (1954) hangs opposite Lunar Surface (1970). The former, recalling Matisse in its bold patterns and heavy lines, depicts a bowl of fruit set against an elaborate curtain, the composition anchored by an ornate blue-and-white vase. While skillful, the work is labored, almost self-conscious. Lunar Surface, by contrast, is pointed in its command of the palette. Rich purples and royal blues resound: Alma has arrived.

In 1972, the Whitney Museum of American Art mounted a solo exhibition of Thomas’s work—the first time the institution gave a solo show to a Black woman artist. The exhibition brochure featured Wind Dancing with Spring Flowers, a work of highly saturated concentric circles that seem to spin the longer you look at them.

“Through color,” Thomas said, “I have sought to concentrate on beauty and happiness, rather than on man’s inhumanity to man.”

But that inhumanity—or, more precisely, the response to it—was the catalyst for her exhibition. It was only after the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition picketed outside the Whitney, demanding that it include more Black artists in its exhibitions and Black curators on its staff, that Thomas was given a solo show.

David Driskell, Thomas’s contemporary and a celebrated artist in his own right, recommended Thomas for the solo exhibition. Driskell, whose work is also on view at the Phillips, wove African art into his own, “keeping alive some of [its] potent symbols,” as he later wrote. Thomas, by contrast, rarely addressed race overtly in her work.

It was during this same time that the Black Arts Movement was taking shape and questioning the value of abstract work like Thomas’s. “[The movement] largely rejected visual abstraction because it was rooted in a European modernist tradition, one that had very little to do, they believed, with the lives and urgencies of Black folks,” as Aruna D’Souza writes in the exhibition catalog.

Read in this light, Thomas’s vibrant paintings, remote as they were from the “urgencies of Black folks” seemed a kind of evasion. But, in Thomas’s formulation, what the painter does with her canvas—the beauty she brings to bear—cannot be bound by social comment.

“Some of us may be black, but that’s not the important thing,” Thomas said. “The important thing is for us to create, to give form to what we have inside us. We can’t accept any barriers, any limitations of any kind, on what we create or how we do it.”

W.E.B. DuBois, whose ideas informed Thomas’s throughout her life, famously said in his 1926 address at the Chicago conference of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People that “all Art is propaganda and ever must be, despite the wailing of the purists.”

But to read this line in isolation is to miss DuBois’s larger vision. For him, as for Thomas, beauty was a worthwhile end, and the task of the Black artist was to create it for herself. DuBois expounds on this in the same address:

Such is Beauty. Its variety is infinite, its possibility is endless. In normal life all may have it and have it yet again. The world is full of it; and yet today the mass of human beings are choked away from it, and their lives distorted and made ugly. Who shall right this well-nigh universal failing? Who shall let this world be beautiful? Who shall restore to men the glory of sunsets and the peace of quiet sleep?

Thomas understood the enduring power of beauty. Active in her community and in her classroom, Thomas in her studio was free to create, to, in DuBois’s words, “let this world be beautiful.”

“Rather than a denial of harsh realities or an escape to alluring oblivion, Thomas’s images generously offer a reprieve from dark times, an opportunity to find our way to the light,” write Seth Feman and Jonathan Frederick Walz, who co-edited the exhibition catalog.

For Thomas, light was as much in the garden outside her window as it was in worlds beyond her own. In Mars Reflection, a royal blue canvas is overlaid with a lattice of fire-red brushstrokes, the blue background breaking through to dizzying effect. “When I paint space,” Thomas said, “I am with the astronauts.” Standing in front of her labyrinthine canvases, the world is, at the very least, more expansive. Implicit in each is her vision for the future:

A new art representing a new era has been born in America. There is a demand that our times be expressed in new forms: the rush of the airplanes through space, or the swift speeding of the high-powered cars, the extraordinary skyscrapers as they crowd each other, the marvelous revolving electrical signals. They have another message besides the material one.

In one of the final rooms in the Phillips show, Thomas’s works are displayed opposite works by Gene Davis and Sam Gilliam, two of her much-revered contemporaries. Seeing them together, one notices the litheness of Thomas’s canvases. Where Davis and Gilliam are sharp, Thomas is rhythmic.

“Thomas herself treated painting as only one facet of a larger, ongoing experiment—a relentless search for beauty,” Feman and Walz write.

One of Thomas’s notes reads: “Love comes by looking.” On a recent afternoon, each person at the exhibition was standing in front of a different painting, letting their eyes travel along the canvas before them, following the twists and turns of Thomas’s lines. No one seemed in a hurry in that moment. The light, at long last, had come around.

*This article was updated on December 8, 2021, to reflect that Sketch for March on Washington is one of a few of Thomas’s works that address race and social issues, something she did rarely.