Of the many historical snapshots collected in And the Band Played On, the pioneering history of the early days of the AIDS crisis written by San Francisco Chronicle reporter Randy Shilts, one of the more prophetic concerned Paul Volberding.

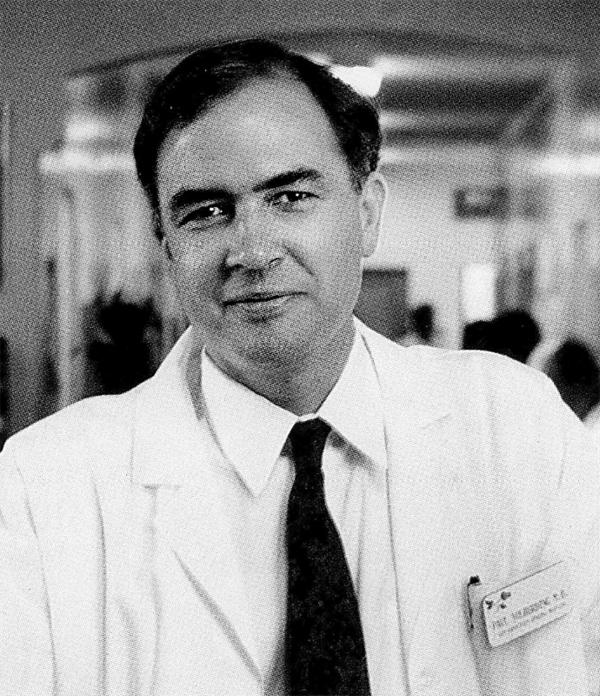

The recently named chief of oncology at San Francisco General Hospital was only thirty-one years old, and it was his first day on the job, July 1, 1981.

He had worked in a lab for the past three years, studying retroviruses, but through an earlier residency he learned he had an affinity for working with the terminally ill. For this reason he left the lab to work directly with cancer patients.

An older specialist kidded him about one of the cases he would see: “There’s the next great disease waiting for you. A patient with KS.”

The man Volberding examined was twenty-two years old and emaciated. His skin was covered in lesions. He had Kaposi’s sarcoma, what was then considered a nonlethal skin cancer usually seen only in older men, and sometimes in people with suppressed immune systems.

There was not much to go on—or to do for the young man, sadly—but it turned out that the cancer specialist was correct. Volberding, who would become a well-known clinician and make several important contributions to the care of people with AIDS, was examining his first HIV patient.

In an oral history collected for the NEH-supported AIDS History Project archive at the University of California, San Francisco, Volberding reflected on the timing. It was a few weeks after the first published report, by the UCLA immunologist Michael Gottlieb, on a rare form of pneumonia affecting gay men, which appeared in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, and just days before another report in the same journal added Kaposi’s sarcoma to the growing list of health issues affecting gay men. Soon it would turn out that these conditions were related and that the larger problem was not limited to gay men, as intravenous drug users, blood transfusion recipients, and heterosexuals were added to the list of potential sufferers.

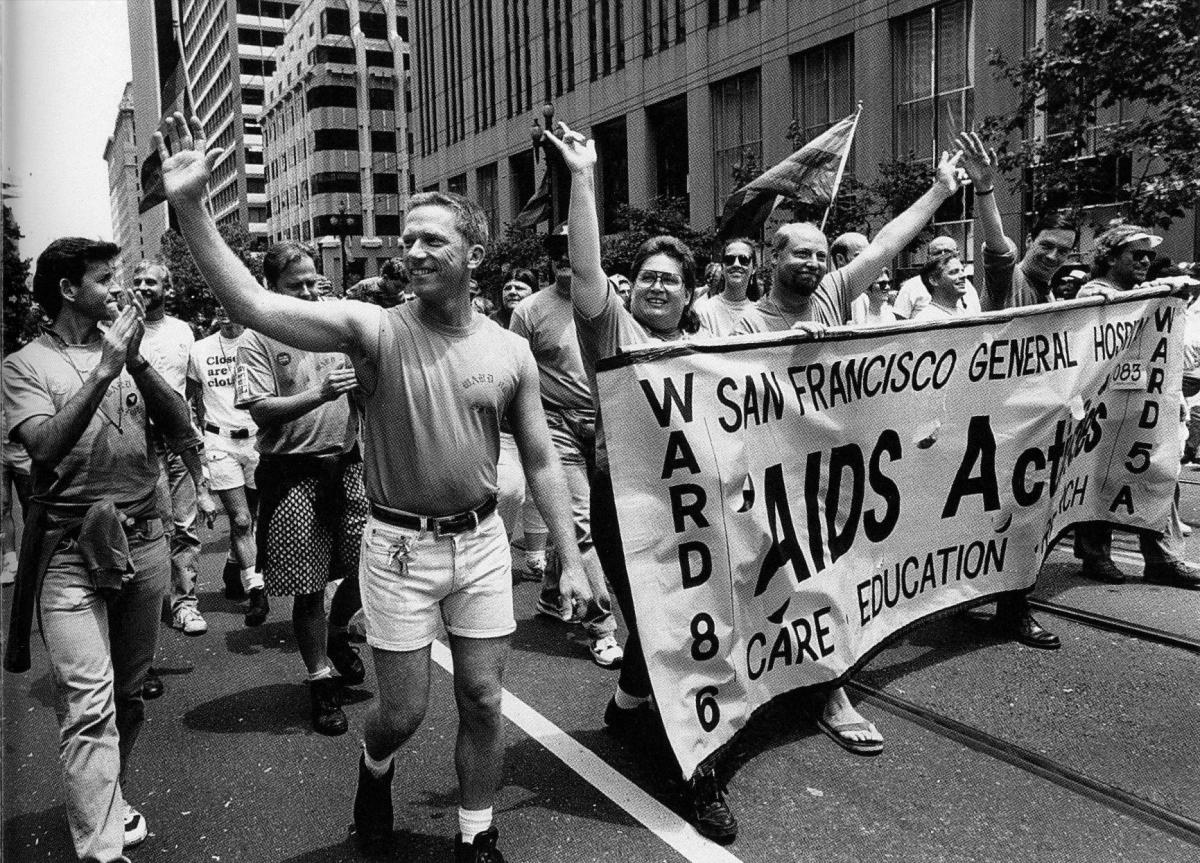

The oral history with Volberding (combining three interviews in 1992 and another in 1995, all conducted by Sally Smith Hughes) offers a valuable download on what the young doctor thought, whom he met, and what meetings he attended during the next 12-plus years as a central figure in the development of what is called the “San Francisco Model.” This humanizing and multifaceted approach to the pandemic sought to reverse the stigmatization of people with AIDS and looked not only across medical disciplines but across the city itself to address the emotional, social, and financial needs of people with AIDS.

Volberding’s memories share space with a number of other oral histories and upward of 50 collections at the AIDS History Project. These include the diary of Bobbi Campbell, who, as the first person to come out publicly as having AIDS, appeared on the cover of Newsweek in August 1983; the papers of Jay Levi, the UCSF virologist who independently discovered the AIDS virus in 1983; the papers of Michael Gottlieb; the papers of Selma Dritz of the San Francisco Department of Health; AIDS-related ephemera; and a strong collection of materials from many community-based organizations such as the Shanti Project, Act-Up Golden Gate, and numerous others.

Recent grants, including $300,000 from NEH to digitize 150,000 pages of materials at UCSF, the San Francisco Public Library, and the Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender Historical Society, have elevated the profile of the AIDS History Project and led to a snowball effect in newly donated collections, says archivist Polina Ilieva.

Clayton Koppes, history professor emeritus at Oberlin College, who has been using the archive as he works on a book about AIDS in the United States, praises the unique assets of the AIDS History Project, its well-organized collections, and its knowledgeable staff.

The AIDS crisis, says Koppes, led to “one of the most profound social upheavals in American society since World War II. Erupting in the middle of the culture wars of the 1980s, the pandemic created huge challenges for the queer community, stimulated divisive political battles, transformed medical research, and generated one of the most consequential activist movements in the past half century: the HIV/AIDS empowerment movement.”

Conceived in 1987 and supported early on by a grant from the National Archives, the archive at UCSF specializes in the history of AIDS in San Francisco, where many early cases were discovered and key medical breakthroughs took place. Its oral histories are cross-referenced with many papers and oral histories within the same archive, such as those of Marcus Conant, another leading figure in the city’s response to the epidemic.

A professor of dermatology (now emeritus) at the University of California, San Francisco, Conant recalls in another oral history his first Kaposi’s sarcoma patients in the spring of 1981 and meeting Paul Volberding, who became codirector of the clinic Conant started that same year. Key names and milestones of the AIDS crisis click by in Conant’s recollections: contacts at the CDC, an early brochure on Kaposi’s sarcoma (also part of the collection), an important meeting with the owners of San Francisco bathhouses, scenes of local politics and the tensions of national politics, the stories of important grants, Mayor Dianne Feinstein, Randy Shilts, and Gaetan Dugas, whom Shilts described as a suspected “patient zero” in And the Band Played On.

The naming of Dugas, a Canadian air steward, as the index case of the North American AIDS outbreak has long been controversial, not least because of the misunderstandings it was based on. The incubation period for HIV, for example, was in reality several times longer than it was assumed to be when Dugas first appeared in the diagrams of CDC researcher Bill Darrow, whose early cluster research drew connections among 40 cases of what was then called GRID (Gay-Related Infectious Disease), helping to establish that the disease was, indeed, infectious and sexually transmitted.

In 2017, the Cambridge scholar Richard McKay, relying on papers at the San Francisco Public Library and related collections at the AIDS History Project, interrogated the scapegoating and public vilification of Dugas in Patient Zero and the Making of the AIDS Epidemic. The origin of the patient zero story had already been traced backward from Shilts’s account to Darrow’s list of cases in which the entry for Dugas appeared without his name as “patient” with an O next to it for “outside California.” At some point, the O was mistaken for a zero and thus Dugas appeared, with some hedging, in Shilts’s book as “patient zero.” Recently McKay has written against the use of the same term, now commonplace, in discussions of COVID-19.

AIDS is a global phenomenon, its ravages known everywhere. The international death toll peaked in 2004 when 1.7 million people lost their lives after becoming infected with HIV. In the United States, at its deadliest, HIV/AIDS claimed the lives of 50,000 Americans in a single year, 1995. Today, thanks to antiretroviral therapy, many more people are able to live with AIDS, but no vaccine has been successfully developed, and somewhere between 1.4 million and 2.3 million people around the world become newly infected every year.

Yet there are places and communities that suffered the plague of AIDS especially and so early on that they came to symbolize its mystifying passage from a seemingly local problem of uncertain origin, affecting only a small number of people, to a vast conflagration of disease taking the lives of millions. San Francisco is one such place, making its experience especially valuable to the larger story of how Americans and others rose, albeit slowly and with many a human flaw, to fight the scourge of a new disease.