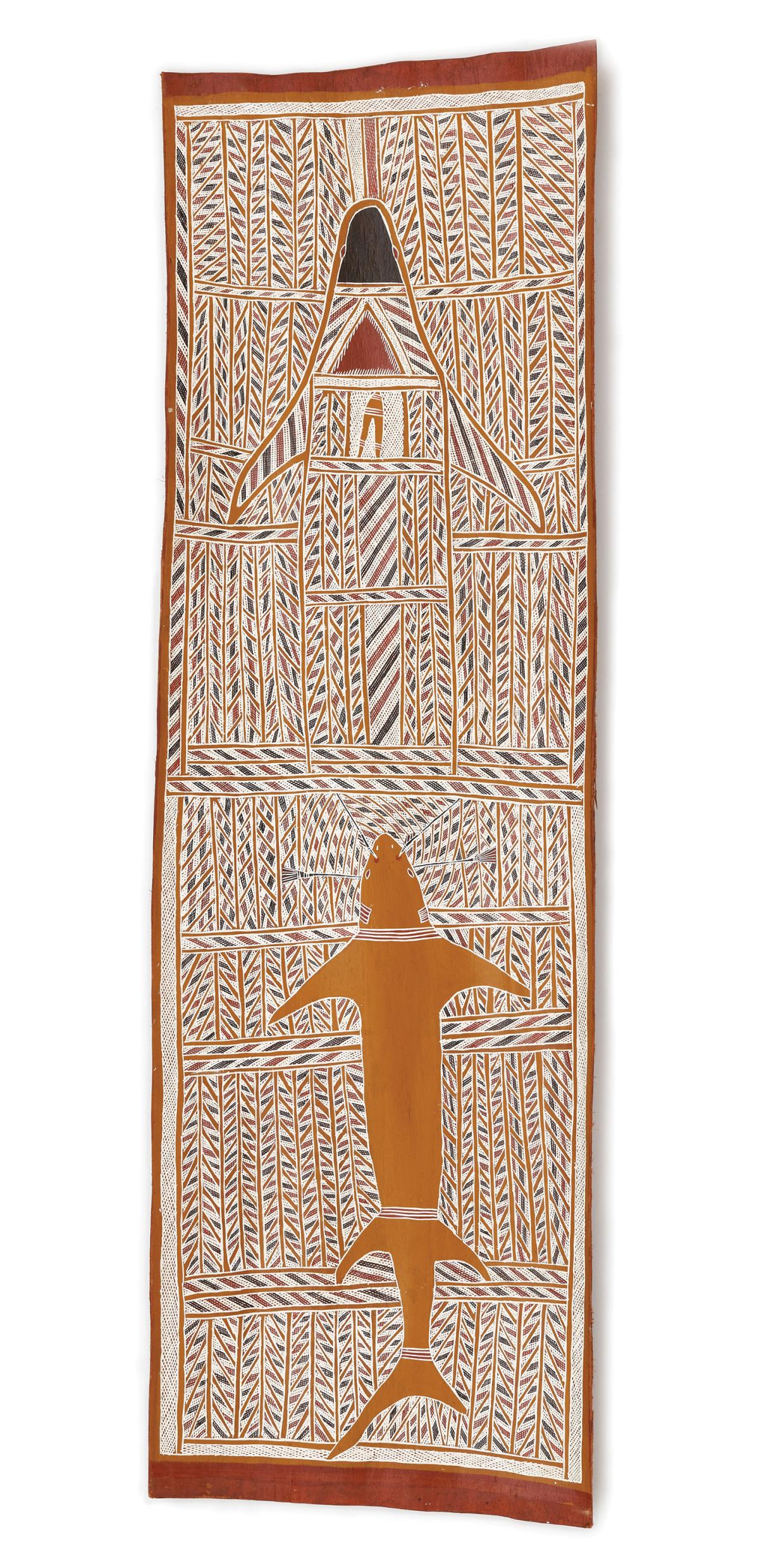

“Madayin,” a monumental survey of Aboriginal Australian bark painting at the American University Museum in Washington, D.C., opens with the image of a shark, anchored in a sea of black and rust-red brushwork, speared. Next, a crocodile shoots fire across an ocean, wire-thin strokes of white giving way to pools of russet and amber.

The show, its name translating to “sacred” and “beautiful,” comprises more than 80 paintings: most elongated, some figurative, and all deceptively simple. What appears at a distance as a dense field of color is up close a latticework of delicately handled pigment, each stroke intentional.

“We want you to come to the grassroots level, to sit in the sand and let us show you a different way of coming to the paintings,” Wukun Wanambi, one of the show’s curators, writes in the exhibition catalog, insisting on a kind of looking as expansive as the pictures themselves. These works on bark, all from Yirrkala in northern Australia, are layered with meaning, gesturing to—or, precisely, embodying—ancestral beings.

To the Yolŋu, or Indigenous people living in the northeast Arnhem Land region (the word “Yolŋu” translates to “people”), these works are far from folktales; they are alive, thunderously, in the here and now.

In “Madayin,” walls of indigo and white are arrayed with variegated, column-like barks: Intricacy is vividly on display. The curators, some of whom are Indigenous artists themselves, let the Yolŋu speak. The show’s bilingual catalog—a series of artist essays presented first in the painters’ native languages, then in English—foregrounds the artists, who are also authors in their own right. Here are people worth knowing, the show proclaims, here is a story worth telling.

The story begins, in “Madayin,” when five Japanese fishermen were killed, in 1932, at Caledon Bay in northern Australia. Three Yolŋu men, sons of the clan leader Woŋgu Munuŋgurr, were sentenced to prison for the murders. Australian anthropologist Donald Thompson was sent to the community on a peace mission, later organizing for the release of Woŋgu’s sons. In thanks, the clan leader painted for Thompson, in 1935, a lively work on bark—the earliest in the show—peopled with lizards, tortoises, and other abstracted designs, silhouetted against a wash of black pigment.

While bark painting in Australia has a long history—there are nineteenth-century accounts of paintings on the walls of bark huts—Woŋgu’s 1935 picture signaled the beginning of the practice in Yirrkala. Preserved under glass in the exhibition, the only work so presented, Woŋgu’s painting is sacred, jewel-like—a superbly rendered claim on the land.

“Every time [the Yolŋu] have their backs against the wall, they have responded by producing art, by producing masterpieces,” notes Henry Skerritt, curator at the University of Virginia’s Kluge-Ruhe Aboriginal Art Collection, which co-organized the show with the Buku-Larrnggay Mulka Centre in Yirrkala. “They have responded to aggression with this beautiful gift of art, and, in the long run, the Yolŋu have prevailed.”

The paintings are more than art. To the Yolŋu, they are a way of keeping ancestral beings alive, of “singing life,” as artist Djambawa Marawili puts it. The poet Mona Tur, writing about Ayers Rock in central Australia, captures something of their pathos: “My heart bleeds, our beloved rock . . . / As evening comes, . . . your haunting beauty / Mirrors beauty beyond compare.”

Midway through the show is a work of electric blues. A departure from the exhibition’s sand-tinged palette, the bark reverberates with a life all its own. Following a car accident, artist Dhambit Munuŋgurr was unable to grind the traditional ochres normally applied as bark pigments and turned instead to acrylics. The effect is arresting. At the azure-blue picture’s center is the sacred rock Dhambit, from which the artist takes her name. Meanwhile, the ground is overlaid with cobalt-blue, Basquiatesque, octopuses. Nothing is still in this bark. Passages of navy and black cut across the visual field like glass shattering.

These bark paintings, Skerritt says, represent “one of the modern and contemporary art movements of our time.”

Indeed, when the National Gallery of Victoria, in 1995, staged a show of Indigenous bark paintings, the director chose to hang Pablo Picasso’s Weeping Woman opposite the exhibition entrance, a nod to the barks’ modernism and their growing popularity.

But this popularity is relatively new. In the preface to a 1965 catalog of Australian Aboriginal bark paintings, the work is described as the “art of primitive people,” adding that the barks are “at first sight simple and ever childlike.”

The Milky Way (2019) is a powerful rejoinder to this. Hanging in the show’s second, half-lit, room, the bark is layered with thick bands of bespeckled black and white pigment. Intercut with four-point stars that seem to emerge and recede, it is suspended, aglow. For artist Naminapu Maymuru-White, the work speaks to two qualities of the Yolŋu aesthetic: shimmering brilliance, or bir’yun, and faintness, or buwayak, the latter harking back to the soul’s transition to the spiritual realm. The work feels hushed, careful not to give itself away. As anthropologist Howard Morphy puts it, the bark exudes “the felt presence of a transcendent spirit seen ‘through a glass darkly,’” referring to Paul’s first letter to the church in Corinth, wherein truth, in this life, is known only obliquely.

Most of the catalog essays open with a kind of disclaimer: “I can only talk of the surface part of the story,” says artist Noŋgirrŋa Marawili. Her work, of orbs oscillating on fields of dust-pink and brown, contains secret or esoteric meanings. For the Yolŋu, each painting tells multiple stories: some restricted and some public. What is restricted, and known only to initiated men, runs parallel to what is public. As Morphy insists, the Yolŋu’s theory of knowledge is cumulative: “The layering is as important as the secrecy.”

Layers abound in Waŋupini (Clouds), a bark piled high with rippling black flourishes. A signal of monsoon rains to come, the billowing clouds float on a cobweb-like bed of razor-thin brushstrokes. The joy is in following the lines, losing oneself at every turn.

A fluidity of perspective permeates “Madayin.” Forms are elusive, patterns break free of their mold: Everything is tenuous. At first glance Retja II (Rainforest II) is a subtle play of blossoms. Up close, its sumptuous, cranberry-red berries spiral, as if rustling in the wind. In the catalog, Wanambi writes, “When we see the flowers blossoming, we sing,” each bud a reminder of the ancestors who will “bloom again.”

In Bonba, an energetic field of russet-red and burnt-orange stripes is interrupted by a flurry of white feather-like forms. The figures, we learn, are by turns humans, butterflies, and kites, their very being flitting back and forth. “Their physical identity is unstable,” anthropologist Frances Morphy writes in the catalog. “They move easily between two states of being.” Here, as elsewhere, the world is in flux.

Traversing the show are stories of the ancestors. Known as songlines, these stories are traditionally sung in ceremonies and are recorded in the catalog and the show’s wall text in a kind of prose-poetry. One songline, reproduced in the exhibition book, recalls lost souls: “The wind comes singing for the dead / Hear its song as it chases over the rocks.” Each line transcends what is, thrilling to what has been and will be. “These songlines,” artist Wanyubi Marika remarks, “take you to another world, different from the physical world.”

By singing these prose-poems, by painting them, the center can hold. These stories, Marika stresses, exist within his very being, never to be lost: “Stand in both worlds if you want. But make sure you hold this one first: your roots and your foundation.”

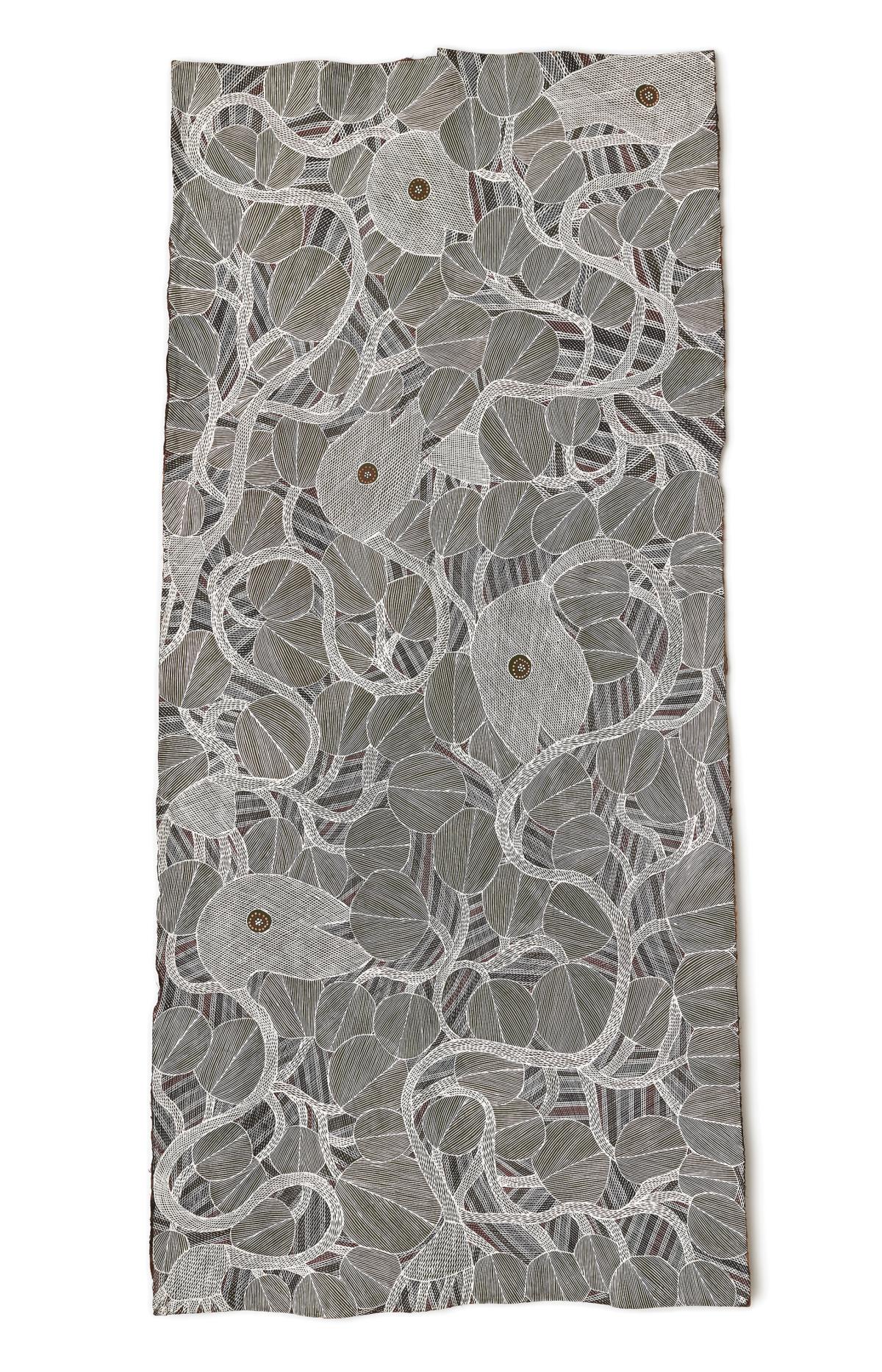

Among the most absorbing works in the show is Dhatam | Waterlily (Nymphaea sp.), a picture of interlocking lace-like spheres softly veiling the deep, receding space. The painting, alive with a silvery tonality, feels impermanent: In a second, it might be gone. Dreamlike, the densely packed water lilies seem to take flight, one after another, then all at once.

The speared shark that opens “Madayin,” we learn in the adjacent wall text, calls out in anguish: “My flesh is broken with weariness / Where is my home?” For a moment, he is lost to us, a mere shadow among forms. But, in the upper half of the bark, we can make out the subtle strokes of his fins, set against the motley pattern of the ground. He has found his way, pronouncing by the text’s end, “Here I am.”